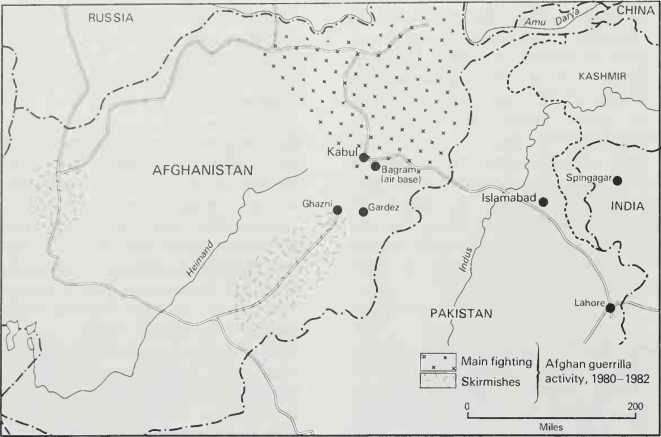

Afghanistan: by mid-1982, mujaheddin resistance to the Soviets resulted in stalemate

Supplied via Pakistan.

The first stage of the conflict focused largely around Afghan communications, and the need to protect Soviet bases from guerrilla attacks. The first major offensive, in Kuran in March 1980, indicated just how ill-prepared the Soviets were for guerrilla warfare. Neither Soviet training, organization nor doctrine had taken this into account, and the Afghan Army, crippled by desertion, was incapable of offensive effort. Units of Fortieth Army were excessively overcentralized. Guerrilla operations had to be coordinated at regimental level, but all support elements, including artillery, were coordinated at divisional level. From June 1980 to June 1981 the occupying Soviet forces, now entitled the Limited Contingent of Soviet Forces in Afghanistan (lcsfa), underwent a major restructuring.

The effectiveness of the resistance of the mujaheddin was reduced by their internal bickering, especially between the fundamentalist and pro-Western elements. Yet the mujaheddin were tenacious fighters. The Soviets were forced to rethink their allarms tactics, relying heavily on air power and helicopter-borne forces to land in the rear of the guerrillas and envelop them. In addition, armoured units were employed to attack their villages and destroy their crops, which served only to stiffen resistance.

In May-June 1982, the Soviets mounted the first of a number of major offensives with a broadly similar character. Operation “Panjsher 5”, which involved 15,000 men and an intense aerial bombardment lasting a week, in an attempt to regain the length of the valley of the Panjsher Gorge. This had been used by the mujaheddin to attack the Soviet air base at Bagram. Although successful, total casualties numbered 2,000, and the operation had to be repeated the following August.

In April 1983, United Nations peace talks began at Geneva. These had, as yet, little bearing on the war, although the Panjsher cease-fire brought major operations to a temporary halt until 1984.

Increasing mujaheddin raids on the Salang Road provoked Operation “Panjsher 7”, involving 10,000 Soviet and 5,000 Afghan troops. The Soviets realized that their earlier offensives had failed because the mujaheddin had slipped away down the side valleys. The area of operations was therefore widened and heliborne forces were used to block this avenue of escape. Tu-16 heavy bombers provided a “rolling barrage” along the valley. Yet no decisive victory was secured.

The second major phase of the war involved Soviet attempts to bring the guerrillas to battle at a disadvantage and to strike at their supply lines in the east. In August 1984 10,000 Soviet and 7,500 Afghan troops swept the Kumar

Valley and relieved Ali Khel — but these successes proved transient. In 1985 a policy of “search and destroy” was introduced. The Soviet problem, like that of the Americans in Vietnam, was how to bring their superior fighting power to bear on an elusive enemy. It was calculated that, by moving into what the guerrillas had previously considered “safe areas” and continually harassing their supply lines, the guerrillas could be either trapped or provoked into fighting a set-piece battle which they could not hope to win. But again like the Americans, the Russians discovered, as for example in the relief of Barikot in May 1985, that once their forces moved into an area, the guerrillas moved out; and they returned the day after the Soviets had departed.

Although other major offensives were mounted by the Soviets, notably “Panjsher 9”, an attempt to locate and release a number of Afghan prisoners taken by the mujaheddin after the fall of Pech-gur in June 1985, the final large-scale operations were launched in the northeast against guerrilla bases and their supply lines. In August 1985 some 20,000 men advanced in a dual thrust, one from Kabul to the Logar Valley, the other to Jalalabad. They were to link up at the “parrot’s beak”, a large salient along the Pakistani border, which was the nearest point of entry for guerrillas making for Kabul. A large heliborne force was able to cordon off mujaheddin bases, then tighten its grip, moving in a five-day battle on Tani, and then on the principal base, Zhawar. A symbol of guerrilla resistance, Zhawar did not fall. But the struggle for the borderlands continued in 1986, when a second attempt was made to seize Zhawar, this time successfully. The guerrillas stood and fought and were defeated, deluded by the belief that Zhawar was impregnable.

World History

World History