The Ohio, Mississippi, and Missouri Rivers," wrote Union General William Tecumseh Sherman, "will control the continent." Through the winter and spring of 1862, ironclad gunboats and mud-caked troops fought for control of these Western rivers that ran deep into Confederate territory.

Fort Henry. In February 1862, a squat and ugly fleet of Union gunboats led by Commodore Andrew Foote steamed up the Tennessee River, heading for Rebel-occupied Fort Flenry. The plan was to capture the Tennessee fort in a combined attack from land and water, and then take Fort Donelson, twelve miles east on the Cumberland River.

At Fort Henry, Union troops led by Ulysses S. Grant went ashore and marched toward the fort's earthen I'am-paits. But the soldiers bogged down in the muddy road already flooded from spr ing runoff. Waiting on the river, Foote gr ew impatient at the ar my’s slow crawl. He decided to pound the fort from the water.

Foote’s fleet steamed upstream to nearly point-blank r'ange of the fort and opened fire. Huge, solid shot plowed gaping holes in Fort Henry’s walls, wrecking the Rebel guns. With the rising river flooding in and only four guns firing, the fort’s commander r'an up the white flag. Union army troops never even made it into the battle.

To Donelson. Most of the Confederates from Fort Henry escaped overland to Fort Donelson, reinforcing the troops already there. Grant’s army followed, and the Union gunboats chugged up the Cumberland River, intending to attack again from the water. Grant’s troops quickly sealed the Rebels inside the fort and waited for the gunboats to begin shelling them out.

Foote’s ships moved within close range of Fort Donelson. But unlike Fort Henry, Donelson was built high on a bluff. When the gunboats fired, their cannonballs failed to hit their mark. Meanwhile, Confederate guns hammered away, cracking gunboat timbers and wrecking Yankee cannons. With two vessels crippled and the rest damaged, the fleet retr-eated downriver. Grant’s army was left to take Donelson alone.

The Confederate garrison was in a tight spot. Though equal in number to the Union forces, the Rebels wer'e trapped against the river. At dawn, under Confeder-ate General Gideon Pillow, they tried for a breakout. In a battle that bloodied the snow all morning, the troops cut an escape route through the Union lines to Nashville. But just before noon, Pillow lost his nerve and pulled back most of his men.

Pillow’s hesitation was Grant’s opportunity. Union troops counterattacked and broke the Confederate lines, trapping the Rebels for good. General Buckner, left in

Avid G.

I Farragut joined the navy in 181 Oat the age of nine; in the War ot 1812 he was put in command of a captured British ship when only a twelve-year-old midshipman.

Before the Civil War he had lived in Virginia with his Southern wife, but when war broke out he had no doubt about which side he was on. “Mind what I tell you,” he said to his rebellious neighbors. “You fellows will

Catch the devil before you get through with this business.”

Capturing New Orleans in 1862 made Farragut a naval hero. Still, though he was already sixty, the triumph over the Southern port wasn’t his last stroke of genius. In 1864, Farragut went after Mobile, Alabama, one of the last Confederate ports still open to blockade runners. In his flagship, the Hartford, Farragut led his fleet into the mouth of the bay at dawn on August 5,1864.

Frail and desperately seasick, the Union commander had himself tied to the rigging of his ship as the fleet sailed single file past the blazing guns of Fort Morgan.

Soon after the attack began, disaster struck. Farragut’s lead ironclad, the

Tecumseh, strayed out of the channel, struck a Rebel torpedo (mine), and plunged to the bottom. The Brooklyn, next in line, halted to avoid the torpedoes. This slowed all the Union ships right in front of Fort Morgan, whose guns blasted the Hartford’s deck, covering it with blood and slaughter. Farragut hesitated a moment, then shouted, “Damn the torpedoes! Full speed ahead!”

The Brooklyn scraped through the minefield and led the fleet into Mobile Bay. Later that morning, Farragut’s ships pounded the Rebel ironclad Tennessee into surrender, ending the battle. Farragut, like Grant, believed that he could minimize battle losses by mounting an aggressive attack. His decisiveness made him the most successful naval officer of the war.

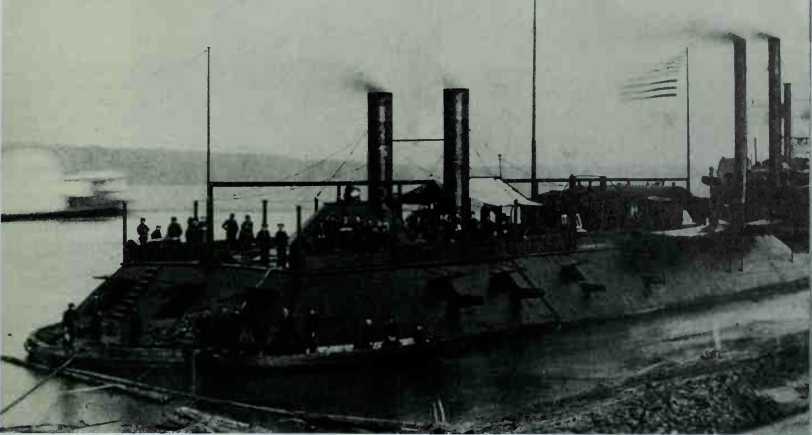

Ironclad gunboats helped force open the western rivers. Their invention rendered wooden ships obsolete.

Charge when Pillow fled, had no choice but to sun'ender. A friend of Grants before the war, Buckner expected generous suirender terms. He didn't get them. Grant demanded "unconditional and immediate suiTender.” His hard line earned him the nickname "Unconditional Surrender” Grant.

Tennessee’s capital, Nashville, soon fell to the advancing Union forces. With that Southern jewel in their pocket and the control of the Western rivers, the Federal armies could now move south.

The Vital Mississippi. In the spring of 1862, while the

Bloodiest battle in the West was raging at Shiloh in Tennessee, Union Admiral David G. Farragut (see sidebar) led a daring campaign to seize New Orleans, the South’s largest city and busiest port. Farragut’s gamble was part of the Union effort to take control of the Mississippi River and split the Confederacy in two.

To apply even more pressure, the Union Navy had been gradually blockading the Southern Gulf coast, cutting off trade and militaiw supplies.

To reach the city, Fairagut’s ships had to get by two Confederate strongholds. Forts Jackson and St. Philip, seventy-five miles east of the city. The forts stood on either side of the Mississippi, and a heavy chain barrier stretched across the river between them. "Nothing afloat could pass the forts,” a New Orleans resident remembered, and "Nothing that walked could get through our swamps.”

Farragut thought he could first shell the forts, then push past the crippled defenses with his powerful fleet.

On April 18, mortar schooners opened fire on Fort Jackson, blasting the brick walls for the next five days. But little serious damage was done, and most of the Confederate guns still growled defiance. On April 23, Farragut decided to run past the forts, whatever the cost.

At 2 A. M. on April 24, Farragut’s ships headed past the forts in the dark. Three nights before, two Federal gunboats had cut a gap in the chain barrier. The lead ship got through the gap before the Confederates spotted the fleet, but soon the night exploded with cannon shells. Burning rafts floated downriver, sent by Rebels to set the Federal ships ablaze.

Fighting the Mississippi current. Union warships steamed with agonizing slowness beneath the forts, firing as they went. But clouds of gun smoke spoiled the aim of the Rebel gunners. Only after the fleet made it through the hairier did a Union vessel go down. By dawn almost all of Farragut’s ships had passed the forts.

A City Surrenders. When Farragut arrived at New Orleans the next day, the city was at the mercy of his cannons. With Union troops aniving just behind Fairagut, the city surrendered on May 1. The gate to the Mississippi, the Confederacy’s largest trade route, was closed.

Union forces continued to press up and down the river, still tiying to divide the Confederacy in two. Fairagut headed north but couldn’t crush the poweiTul Rebel guns at Vicksburg, Mississippi. He was forced to return to New Orleans. Union General Grant would soon grasp again for Vicksburg’s valuable Mississippi port.

World History

World History