1917-18; Falcon-powered version exceptionally successful. Arab-powered reconnaissance/artillery-spotter version little used. Over 4,400 built to wartime contracts; production continued after Armistice. One 275hp Rolls-Royce Falcon III or 200hp Sunbeam Arab engine; max. speed 119mph (190kph); two or three 0.303in machine guns, up to 3001b (135kg) bombs.

Bristol Scout (Br, WWI). Singleseat fighting scout. Prototype flew February 23 1914; first production delivery February 1915. Widely used RFC and rnas France, UK, Aegean, Middle East; popular but never effectively armed; never equipped an entire squadron. Pioneered deck flying. Total built 374. One 80hp Gnome, Le Rhone or Clerget, or lOOhp Gnome Mono-soupape engine; max. speed 94mph (150kph); one, occasionally two, 0.303in machine guns, a few small bombs.

Britain the Battle of (July-September 1940). One of the decisive battles of World War II. The German aim was to engage and destroy the raf and thus to neutralize the Royal Navy which would have been unable to operate effectively in the face of overwhelming air attack and without any air cover of its own. The German army would then have been able to occupy Britain without undue difficulty. The Germans thought that this could be achieved by fighter-escorted bomber raids on targets which the British would feel compelled to defend. They expected that in the resulting air battles they would quickly gain the upper hand and that within a matter of days the effective fighting strength of their enemy would be destroyed. As they could choose the times and the targets for the attacks and as they had bases all the way from Norway to the French Atlantic coast, the Germans seemed to have the advantage of the element of surprise; they also had an apparently decisive superiority in strength, with about 2,500 aircraft available to take on the 1,200 or so of the RAF. After preliminary skirmishing in July—August, the battle began in earnest on August 13, which, after many postponements, the Germans named Adlertag (Eagle Day). It ended on September 15 by which time the British had inflicted such losses on the Luftwaffe that it was compelled to disengage. A few days later. Hitler cancelled “Sealion”, the plan to invade Britain. The issue had been decided in air combat between fighters, the best of which were the British Spitfires and the much more numerous German Messer-schmitt Me 109s; these were fighters of comparable performance. The British Hurricanes,

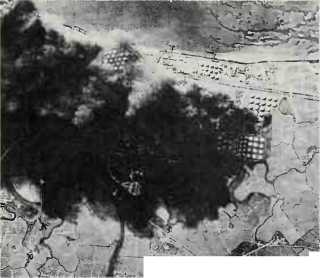

German photograph of Newhaven, 1940

Although outclassed by Me 109s, were superior to the longer-range German Me 110s and the German bombers of all types were highly vulnerable to any of the opposing fighters. The apparent German advantage was more than neutralized by two key factors which they had not anticipated. First, the element of surprise was largely negated by the British radar early warning system, assisted to some extent by “Ultra”, which enabled the British to put their fighters in the right places at the right moments. Secondly, the German advantage of superior numbers of first-class fighters was qualified by their lack of range. The Me 109s, which had less than half-an-hour of fighting time over England from their nearest bases, were often out of the action before they could bring their potential to bear. There was also the general consideration that German fighter pilots had to attempt to screen their bombers in addition to engaging the British fighters, whereas the latter had free aim at anything hostile they could see. It was also fortunate for Britain that the c-in-c of Fighter Command, Dowding, declined to rule in favour of either of his two principal Group Commanders, Leigh-Mallory and Park, who were in vigorous dispute as to tactics. Park thought it best to feed his fighters into the attack as and when they arrived on the scene. Leigh-Mallory preferred to assemble an overwhelming force and attack only after this had been achieved. In the event it was the combination of these two ploys which proved the most advantageous.

It may be concluded, although this must for ever be a hypothesis, that the Germans lost the battle because they failed to concentrate the RAF at some point where they could bring their superior strength to bear. Due to the range of their Me 109s, such a point could only have been Kent and East Sussex, and had the Germans made even a limited and, no doubt, a costly military landing there to draw the British defences into the range of their effective air power, the Battle of Britain would probably have had a German name. ANF.

Britain, planned invasion of

(1940). No real plans had been drawn up for an invasion of the United Kingdom before the summer of 1940, and Hitler harboured hopes of a negotiated peace with Britain. Nevertheless, he issued a directive on July 16 1940 ordering the German army and navy to prepare for a cross-Channel assault on the coast of southeast England, codenamed Operation “Sealion”. The British rejection of Hitler’s peace terms in July led to increased preparations for invasion but, although the British army was weak, both the Royal Navy and the raf remained daunting adversaries. The fate of “Sealion” depended upon the outcome of the Battle of Britain and the invasion forces were obliged to postpone and modify their plans throughout most of the summer. The British victory and the onset of adverse seasonal weather in the Channel, combined with Hitler’s desire to pursue his ambitions elsewhere, led to the effective abandonment of the venture. MS.

World History

World History