The amphibious task force which would I transport, land, and support the Marines j was commanded by Rear-Admiral Richmond K. Turner; overall commander of the naval expeditionary force, including carriers and their escorts, was Rear-Admiral Frank J. Fletcher. Since this was to be a naval campaign and the landing force was to be of Marines, Admiral King had insisted that it be conducted under naval leadership. Accordingly, the Joint Chiefs-of-Staff shifted the boundary of Vice-Admiral Richard H. Ghormley’s South Pacific Theatre northward to include all of the 90-mile-long island of Guadalcanal, which precluded the possibility that General Douglas MacArthur, the South-West Pacific Area commander, would control operations.

The plan for the seizure of the objective, codenamed "Watchtower”, called for two separate landings, one by the division’s main body near Lunga Point on Guadalcanal and the other at Tulagi by an assault force made up of the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines and the 1st Raider and 1st Parachute Battalions. In all. General Vandegrift had about 19,000 men under his command when the transports and escorts moved into position on D-day. They had come from a rehearsal at Koro, in the Fiji Islands, where the inexperienced ships’

V Shattered and half buried by American bombardment: Japanese bodies on the beach at Guadalcanal, killed before they even had the chance to close with the Marines.

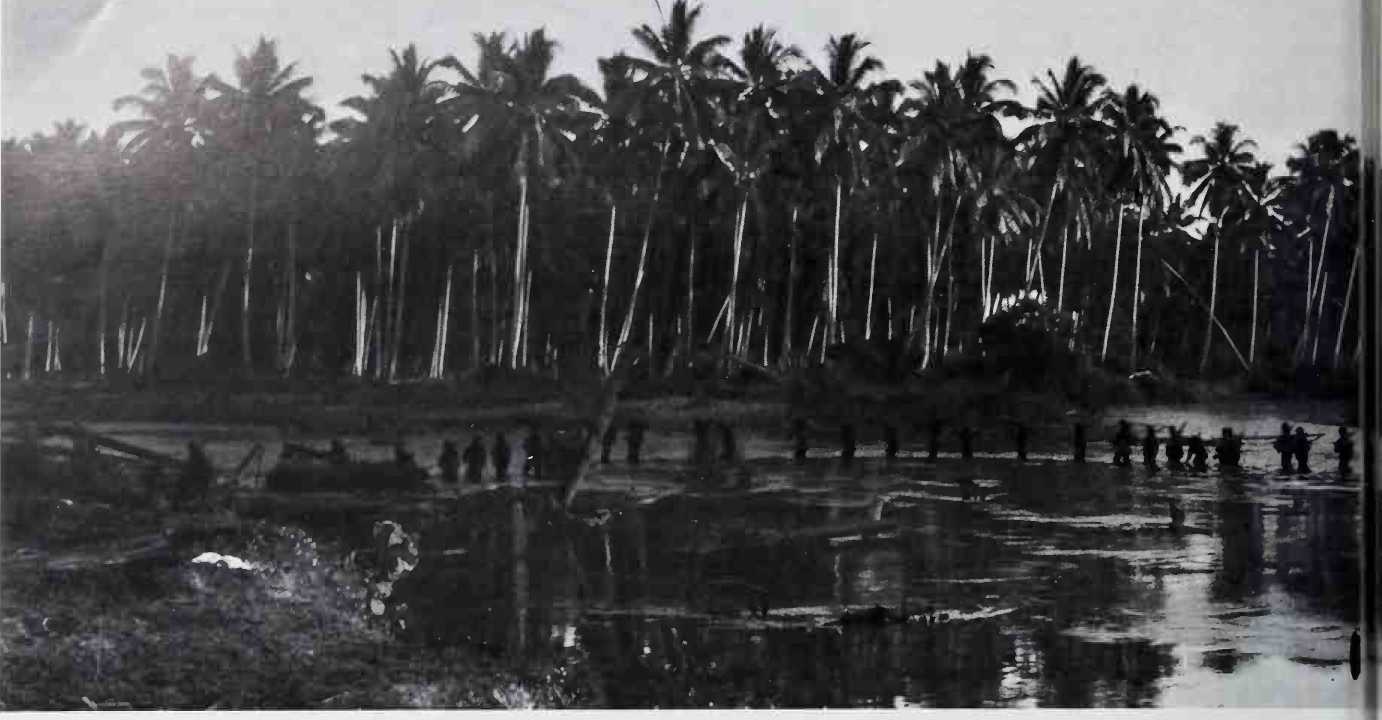

River.

A A dusk patrol sent out by Vandegrift’s Marines sets out, tramping through the Matanikau

Crews and the polyglot Marine units reinforcing the 1st Division had combined to take part in a run-through that General Vandegrift called a "complete bust”.

Behind a thunderous preparation by cruisers and destroyers and under an overhead cover of Admiral Fletcher’s carrier aircraft, the landing craft streaked ashore at both targets. Surprise had been achieved; there was no opposition on the beaches at either objective. True to preliminary Intelligence estimates, however, the Japanese soon fought back savagely from prepared positions on Tagula.

It took three days of heavy fighting to wrest the headquarters island and two small neighbouring islets, Gavutu and Tanambogo, from the Japanese naval troops who defended them. All three battalions of the 2nd Marines were needed to lend their weight to the American attacks against Japanese hidden in pillboxes and caves and ready to fight to the death. The garrison commander had radioed to Rabaul on the morning of August 7; "Enemy troop strength is overwhelming. We will defend to the lastman.” There were 27 prisoners, mostly labourers. A few men escaped by swimming to nearby Florida Island, but the rest of the 750 to 800-man garrison went down fighting.

On Guadalcanal, the labour troops working on the airfield fled when naval gunfire crashed into their bivouac areas. Consequently, there was no opposition as the lead regiment, the 1st Marines, overran the partially completed field on August 8. Japanese engineering equipment, six workable road rollers, some 50 handcarts, about 75 shovels, and two tiny petrol locomotives with hopper cars, were left behind. It was a good thing that this gear was abandoned, for the American engineering equipment that came to Guadalcanal on Turner’s ships also left on Turner’s ships, which departed from the area on August 9. Unwilling to risk his precious carriers any longer against the superior Japanese air power which threatened from Rabaul, Admiral Fletcher was withdrawing. Without air cover. Turner’s force was naked. Japanese cruisers and destroyers and flights of medium bombers from Rabaul had made the amphibious task force commander’s position untenable.

World History

World History