It is clear from Himmler’s explanations to the S. S. at Poznan in 1943 that a turning point was reached with the "extermination through work” plan, and that those concerned knew it very well. Recalling 1941 (and nothing shows more clearly that until then the 1939 decision of principle had not yet been put into effect) he said: "We didn’t look on this mass of humanity then in the same light as we do now: a brutish mass, a labour force. We deplore, not as a generation but as a potential work force, the loss of prisoners by the million from exhaustion and starvation.” Let no one be deceived. Himmler and the S. S. had not been converted to economics.

The usual plundering of Jews’ property was a by-product, not a cause, of their deportation. G5ring was able to claim: "1 received a letter written by Bormann on orders from the Fiihrer requiring a coordinated approach to the Jewish question. As the problem was primarily an economic one, it had to be tackled from the economic point of view.” He was preaching to the wind. Selection was to go on as in the past. No examination was made of a detainee’s real qualifications or state of health. Selection on arrival and inside the camps was still an act of terror.

The supreme criterion was still the disintegration of human beings, their abasement, and their slow death, however. Whatever the importance of this turning point, it did not affect the essential function of the camps. It merely gave them a different emphasis. The real, the crucial discovery was that through a concentration camp labour-force two key objectives were reached: production was maintained, and punishment meted out.

The second major discovery was that the labour force increased the power of the S. S. so much that it transformed it. However, right to the very end, the norms of destruction were more important than those of productivity: those who survived the camps know this well. This comes out of the statutory instruments so clearly

Li

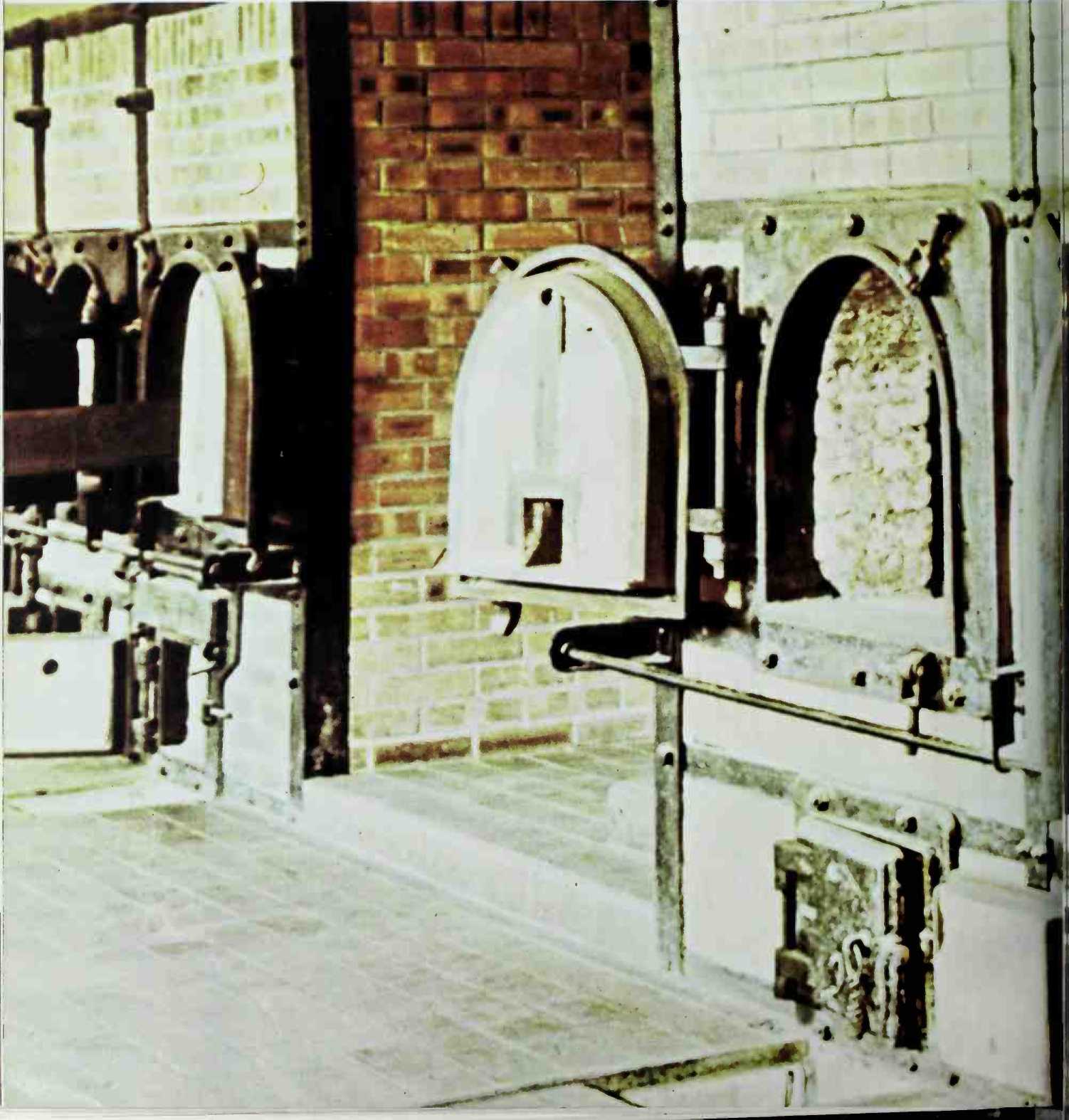

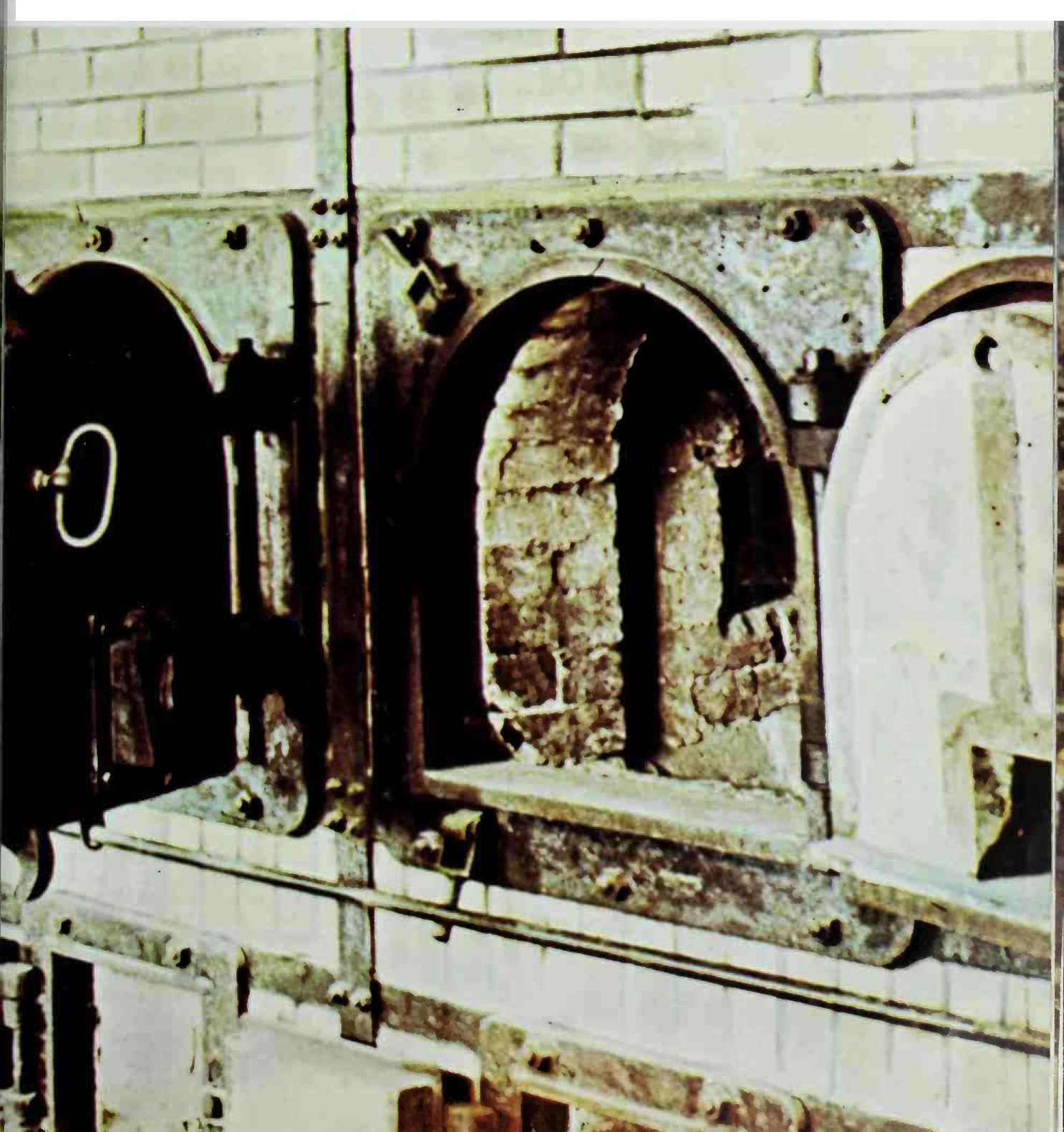

The ovens of Buchenwald.

That these can show the difference in law between slave labour and concentration camp labour. The slave - or serf-owner took elementary precautions in his own interests, and in the interests of production, to keep the labour force alive. The concentration camp saw to it that everything was done to exterminate the labour force by wearing it out. If economic sense and logic were to prevail, this would

Clearly be aberrant. This constant will to destroy had one far-reaching consequence: the need for a rapid renewal of the work force. All legal decisions became null and void in the face of this need. The slightest accusation, well-founded or not, the most commonplace of court sentences could open the gates of the camps when there were numbers to make up. People would be hounded down

As the war lengthened and began to turn against Germany, manpower losses at the front dictated that industrial workers be conscripted into the armed forces. The only way that these workers could be replaced in the vital industrial and allied spheres was by drafting in forced, or slave, labour from occupied countries or turning the populations of the concentration camps into workers. Both systems were put into practice, and the development of the latter finally made the S. S. all but an independent state within the Reich.

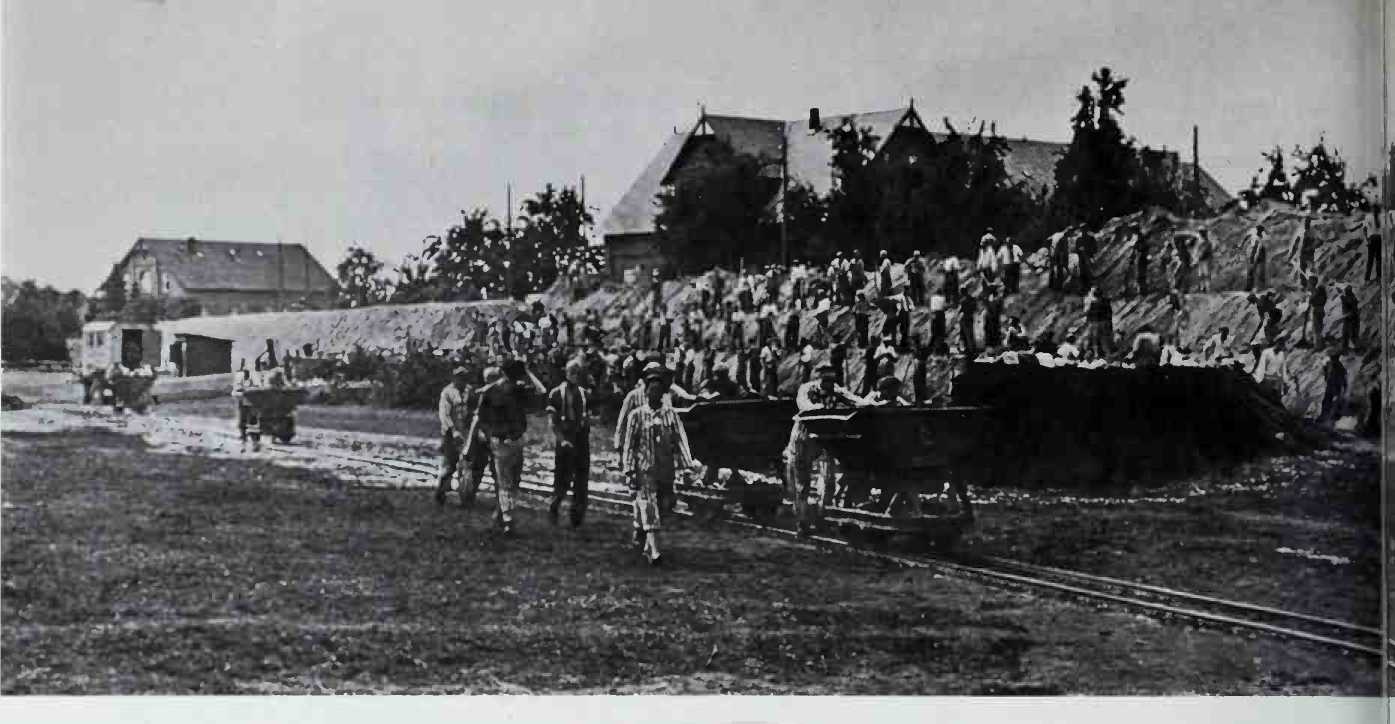

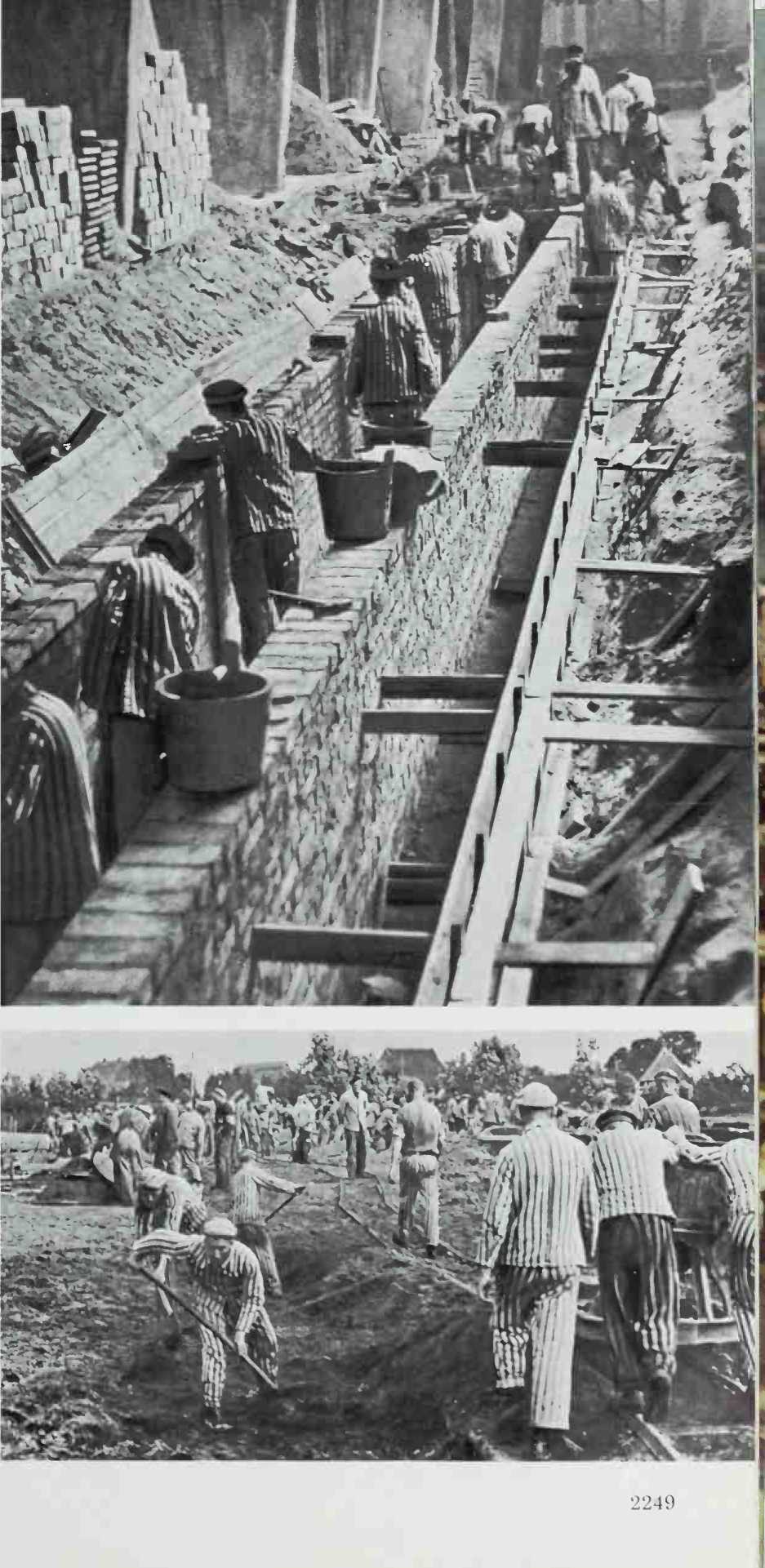

A Concentration camp workers clear away a hill at the edge of a new airfield.

A > Preparing the foundations of a new factory.

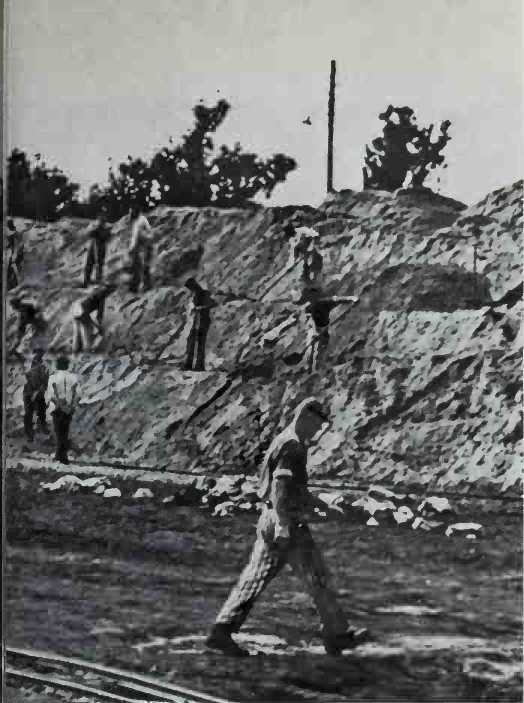

> Airfield levelling.

By terror more than ever. Yet these swoops by the secret police had their fixed basic rules. Transport difficulties were so appalling that the losses in transit were enormous. The pressure of events was relentless.

The cause of the turning point lay completely in the unexpected prolongation of the war, in the great extent of the front, in the continuation, in spite of everything, of Blitzkrieg strategy, and in the effects of all this on manpower and industry. It was in the winter of 1941-42 that Field-Marshal Wilhelm Keitel raised the whole vital question of manpower. The army needed an annual reserve of two to two and a half million men. Normal recruitment, plus the return of the wounded and some barrel-scraping, could produce only one million. This left a million and a half to be found elsewhere. "Elsewhere” could only mean on the production lines. Factories had therefore to work at full capacity and beyond it to meet the ever-increasing needs and to make up for the now dangerous contribution to the Allied effort from the United States. So the whole of Europe had to be mobilised, and this could only be done by intensifying constraints and terror.

The general staff of the forced-labour administration consisted of Keitel, Speer, Sauckel, and Himmler. Keitel was responsible for the recruitment of army, navy, and air force reserves. Albert Speer ran the Todt Organisation from February 15, 1942, and was then put in charge of what, on September 2, 1943, became the Ministry of Armament and War Production. Fritz Sauckel, nominated General Plenipotentiary for the Allocation of Labour, had the job of putting into effect the forced labour programme. Finally Himmler was the number one contractor.

This very considerable undertaking brought a clash between two branches of state service under Keitel and Speer on the one hand and Himmler on the other. Keitel represented military bureaucracy and Speer the joint interests of the state and powerful private enterprise, and his was a key ministry, as it brought monopolies into the state system. High-ranking management jobs were given to industrialists who at the same time remained in charge of their firms. Sauckel was merely an executive. Speer indicated to him what was wanted, Himmler provided the means. Sauckel co-ordinated. In January 1944, when Hitler ordered Sauckel to recruit four million workers, Himmler replied that to get them he would increase the number of concentration camp detainees and make them all work harder.

The matter which brought Keitel and Speer up against Himmler was the key question of who owned the forced labour gangs, and in particular the concentration camp labourers. Keitel and Speer said the state, which had sovereign rights over them. Himmler replied the S. S., and to employ them there had to be a contract with his economic service or, more

2248

Precisely, with his Amtsgruppe D, which ran the camps, or with the K. Z. commandants who, under the Pohl ordinance, had sole control of the use of the camp labour force. Fundamentally what was at stake was the ownership of the slave and concentration camp labour and the position of all hostile elements in production andsociety. AtNurembergKeitelrevealed Himmler’s empire-building, his constant efforts to bring under his control prisoners-of-war, and then foreign and requisitioned workers.

In September 1942 Hitler was called upon to settle the differences between the two totally opposed sides. Speer proposed that private enterprise should take over the camp detainees. His main argument was that this was the only way to get high productivity. Himmler retorted that industries should be set up inside the camps, as only the S. S. were legally qualified to deal jointly with the needs of production and repression. Speer objected that this could not be done because of the shortage of machine tools. Himmler agreed to a compromise: some industries to be set up in the camps and some camps to be organised around existing industries. Factories would be built in regions where there were large concentration camp complexes. The ownership of the concentration camp labour force was recognised as belonging in law and in fact to the S. S. Private management and monopolies were required to pay to the S. S. a fee for each prisoner employed for the whole time he worked for them.

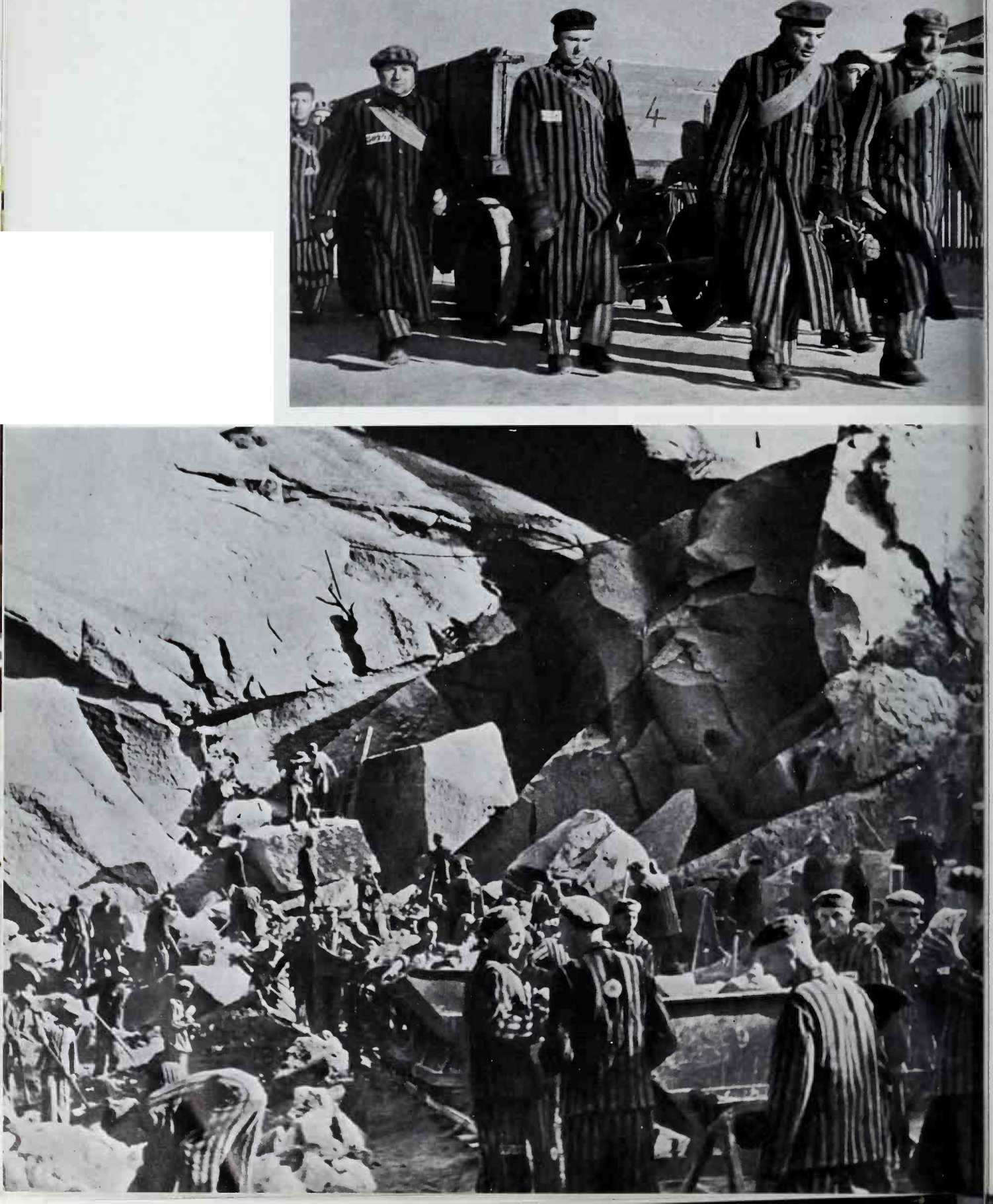

> Germany was short not only of manpower, but also of fuel and draught animals, as these men from Sachsenhausen camp harnessed to a waggon bear witness.

V Some of the hardest work of all for debilitated prisoners: quarrying.

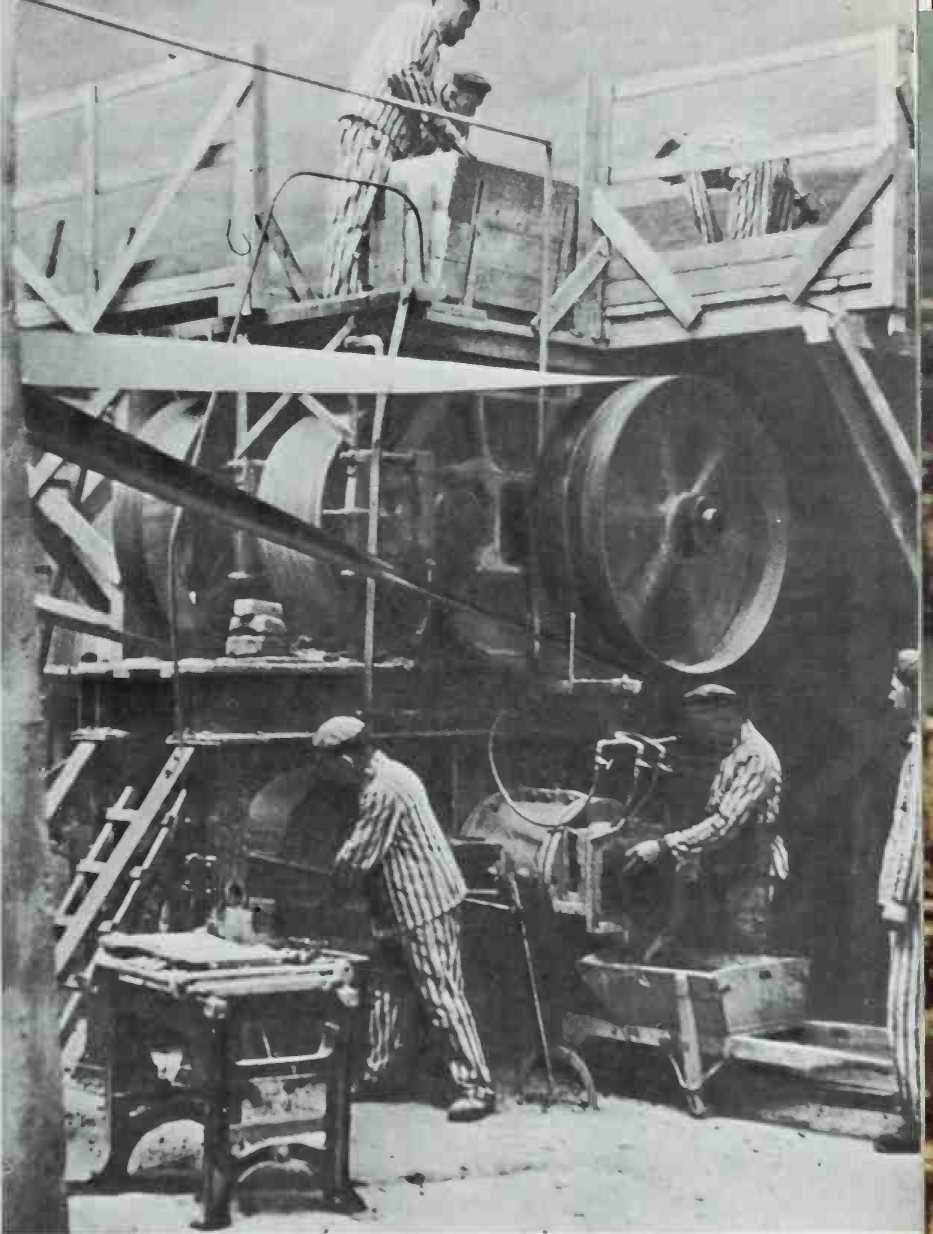

A Prisoners from Oranienburg, part of the Sachsenhausen complex in Brandenburg, operating a huge cement mixer during the building of a factory in Berlin.

Moreover, Speer had to agree to turn over to the S. S. five per cent of all the arms made by the detainees. A conflict of principles was to become a conflict of execution. Himmler got his way then, because he was indispensable. To get the workers they needed, Keitel, Speer, and Sauckel had to use the S. S. and its terror methods. They may have disliked it but they could not do without it. The logic of the system worked for the S. S.

Behind all this there were totally opposed ideas. For Speer the decisive criterion was productivity. For the Party and the S. S. it was terror, as a social function. Speer won the concession, against the Party, that Jews could work in arms factories. On Hitler’s order they were to be excluded in 1943 and in spite of this order 100,000 Hungarian Jews were to work in underground factories in 1943. This gives Goring’s letter quoted above its true meaning.

The S. S. had made its final change and become an economic power. The importance of this was not that it achieved great wealth collectively by this change, but that it obtained the final means for its independence and established its stranglehold on the state.

The only by-product of extermination which brought in huge fortunes, the gold from the Jewish corpses at Auschwitz and the valuables taken from deportees, were deposited in the Reichsbank, where by an agreement between Dr. Walther Funk and Himmler they were credited to the S. S. in an account entered under the name of "Max Heiliger.” The deposits came so quickly and in such large quantities that to clear the vaults the bankers went to pawnbrokers and turned them into cash.

World History

World History