The tank had been invented in order to break the deadlock of trench warfare. Used as a mobile armored pillbox, it could advance in the face of machine-gun fire and crush the vast fields of barbed wire that filled no man’s land. Ability to cross trenches was considered far more important than firepower, and protection more important than speed. The war ended with very long, very heavy tanks, which were so slow that they became vulnerable to artillery fire. No matter how much the theorists insisted that a really fast tank (in the 20 to 30 mph category) would transform the very nature of war, the fact was that the war had ended with the tank no more than a rather ineffectual infantry support weapon. For the staffs of most armies, it remained so until the next war began.

The nineteenth-century world of peasants and gentry, in which horse and carriage marked the divide, was being undermined. Cheap motorcars poured from the factories. Henry Ford’s Model T went on sale in 1908; by 1915 the number had risen to a million and by 1924 no less than 10 million Fords had been made. Mass production began a social transformation which is still continuing.

But the men of the postwar armies did not want to believe that their world might change too. When the First World War ended, the French and British professional armies resumed a peacetime life-style that centered on the cavalry regiment. It was a time when all professional soldiers had to make do with obsolete equipment and small budgets. It was inevitable that the newly formed tank arm should be squeezed hardest, and requests for new equipment or a chance to experiment were usually answered by reminders about the old tanks left over from the war. Having given the slow tanks to the infantry, any new faster tanks were given to the cavalry to be used as tin horses.

BLITZKRIEG

Perts had all agreed about the role of the tank in future warfare. Every permutation of tank, infantry, and artillery was advocated. Many were tested in peacetime exercises. During this time it was usually the infantry which emerged as the strongest detractor of the value of the tank in battle. The cavalry, which had had little or no fighting role throughout the First World War, was beginning to realize that unless it adapted to this new armored vehicle, its regiments would become extinct and finally be disbanded. But the infantry had done almost all the fighting, in appalling conditions, and many infantry generals were jealous of the publicity, funds, and promotions that the new tank arm had received during the war. Opinion polarized as the dispute continued. The extremists among the tank men wanted armies composed solely of tanks with no supporting arms whatsoever. On the other hand, the infantry demanded very heavy tanks that could move no faster than a fully equipped infantry soldier and would remain under the infantry officer’s direct control.

The more perceptive of the tank theorists were stressing the importance of versatility. They believed that infantry, signals, engineers, and artillery should all be equipped with armored fighting vehicles on caterpillar tracks, thus giving the whole army “cross-country capability.” It could be supplied either by air or by other tracked vehicles.

There were also fears for tanks that attempted to operate beyond the range of artillery. In May 1937 Marshal Mikail Tukhachevski— soon to be a victim of Stalin—wrote that “tanks, like infantry, cannot successfully act in combined troop combat without mighty artillery support.” This idea, shared by the French High Command, was responsible for much of the French complacency before the German advance of 1940.

All the arguments contained a large measure of vested interest. Many senior officers, with allegiance and nostalgia for the chic regiments to which they had devoted their youth, did not relish the idea of divisional—or even corps—conferences at which a tank man in oily overalls gave the orders, for tank armies would have tank generals in command. The “old guard” preferred to have tanks dispersed throughout the army and used in the support role, thus making it as difficult for a tank man to command a division as it already was for the other specialists.

The dilemma facing the planners at that time must not be underestimated. How could these expensive motor vehicles and tanks be integrated into the army? There were several alternatives. First, the speed of the mobile forces could be kept down to that of marching men. But slow tanks had failed in 1918, and with the promised improvement in antitank weapons, they would probably prove an even more dismal failure.

Second, trucks and tanks could be given to the whole army. Here the cost—to say nothing of the availability—of raw materials made such a plan prohibitive even for a small professional army. And what became of men mobilized for war?

Third, part of the army could be separated off and given motor vehicles while the remainder marched. But which part of the army needed mobility most? And how would the mobile army get its supplies? Would such relegation demoralize that part of the army denied motors? In France such a course would almost certainly bring an end to the policy of peacetime conscription.

Cost was the ever-present limitation. Before Hitler came to power, there seemed very little prospect of the British Army being called upon to fight a European land battle. Theorists spoke of “the expanding torrent” in which armored forces, with close air support, made deep penetrations through fortified fronts. Such expensive ideas were far too Napoleonic for an army mainly concerned with putting down riots in the colonies.

For the. British and French armies, the interwar years were a time of policing. For dealing with rebellious Indians or Arab tribesmen nothing was better than the fast, cheap, lightly armored little tanks with one machine gun. Smart cavalry regiments reluctantly reequipped with them. Such tanks could chase horsemen, climb steep outcrops of rock, and easily deflect the low-velocity bullets of the rebels’ muzzle-loading rifles. On a European battlefield, however, nothing could have been less suitable, except perhaps a horse.

There were political considerations too. The major powers had to keep a broad industrial base if they were to continue to manufacture their own weapons. Still today, governments prefer to subsidize inefficient shipyards or profligate aircraft factories than face the political pressure that invariably comes from countries which sell armaments. It remains unwise to ban the sale of armaments to nations whose policies one wishes to change; they will need spare parts, repairs, and replacements and will have to bargain for them.

The cost of maintaining an industrial base can be relieved by foreign sales. So between the wars, British and French tanks were likely to be a compromise between what the armed forces wanted and what could be sold overseas.

In the British Army, despite some promising experiments, the exponents of tank warfare were totally vanquished by the combined efforts of advocates of the old school. By modifying infantry and cav-airy units to take tanks, they had been able to frustrate all attempts to form permanent armored divisions. They winkled Fuller from his job as adviser to the Chief of the Imperial General Staff. They shamelessly rigged the autumn maneuvers of 1934 in order to discredit the improvised armored force that took part in it. The director of army maneuvers that year had more or less announced his intention beforehand, saying that he wanted to restore the morale of the older types of troops. To consolidate this campaign, the Royal Tank Corps experiments were discontinued and its best leaders sent to other jobs, with infantry or anti-aircraft units or to administrative posts in India.

The men who opposed the tank arm rationalized their opposition by believing every claim about the development of antitank guns. It was said that antitank guns were so powerful that they had made the tank virtually obsolete. Like so many other dire warnings of the same kind, these claims proved unfounded. The German 3.7 cm Pak (Pan-zerabwehrkanone, or antitank gun) was the best in general use anywhere in the world, but after 1940 the Germans gave urgent priority to getting improved ammunition and a bigger and better antitank weapon, the 5 cm Pak.

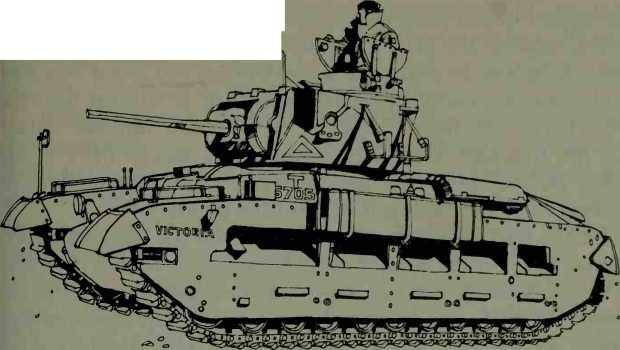

Hugh Elies, the first commander of the Royal Tank Corps, who had personally led his tanks into battle in the First World War, later lost faith in tanks. In 1934, when Master General of Ordnance, Elies decided that tanks would be of little use in future in any role other than the one they had had in those early battles. He ordered new tanks to be built to withstand all known antitank missiles. It was an absurd stricture, impossible to apply to any item of war, from battleship to bomb shelter.

This order resulted in the Infantry Tank Mark I, which went to war in France in 1940. It weighed 11 tons and had a top speed of 11 mph. Its commander aimed, loaded, and fired its sole armament, a machine gun, as well as commanding, navigating, and operating the radio. The only other member of the crew was the driver. As a war weapon, it was even less effective than the German PzKw I (Panzer-kampfwagen) training tank.

In March 1938, believing war to be imminent. General Sir Edmund Ironside, soon to be Chief of the Imperial General Staff, noted in his diary that his army had no cruiser tanks, no infantry tanks, and only obsolete medium tanks. When war began and the Ministry of Supply had taken over from the Master General of Ordnance, Ironside asked the ministry about new tanks. He was given the astounding answer that there were two committees going their separate ways on tank design.

FIGURE 2 Matilda Mark II infantry tank.

Neither had any contact with the General Staff, so they knew nothing of the army’s needs.

The RAF cared even less about the army’s needs. An RAF unit that obliged the army with a demonstration of “ground strafing” got a sharp letter of complaint from the Air Ministry. RAF cooperation with the army, the Air Ministry decided, must be solely confined to reconnaissance flights.

The RAF, long since a congenial haven for the worst sort of “Colonel Blimp,” was terrified that any cooperation with the army or navy might reduce its status as an independent arm of the fighting forces. Not interested in the theories or practice of air support, which had been proved so vitally important in the First World War, it clung tight to the crackpot prophecies of men such as Douhet, who said that bombing fleets could win wars without the help of other services.

The same spirit of Colonel Blimp kept the RAF resolutely opposed to dive bombing. In late 1937, the chief test pilot of Vickers returned from Germany where he had flown the excellent Junkers Ju 87 Stuka. The Vickers chairman thought his enthusiastic report important enough to pass on to Britain’s Air Minister but he was advised to “kindly tell your pilots to mind their own bloody business. . .”

So many decades after the event, it requires a considerable effort of mind to re-create that Europe of 1940, when France was a mighty power and her frontiers impregnable. Yet without that effort there is little chance of understanding the initial German victory.

The almost universal opinion that the war would continue in a stalemate provoked many into wondering if the belligerents would eventually be forced to come to terms. Liddell Hart had consistently

Advised against British participation in any European land battle, and he opposed sending the British Expeditionary Force to France. This was because he saw no chance of a breakthrough by either side and wanted Britain kept out of a long exhausting war of attrition like that of 1914-1918. Far from predicting the German armored thrust through the Ardennes, Liddell Hart specifically said in 1939 in his book The Defence of Britain that a large-scale movement through the Ardennes was not possible because of the terrain.

In Liddell Hart’s view, the French Army did not need assistance from Britain; the French Army was more thoroughly trained than that of the Germans, which had expanded too much and too quickly. He interpreted the fighting in Spain and China as showing the increasing strength of the defensive, so that even poorly equipped and poorly organized armies could defeat an attacker. He did not move far from this view even after the German invasion of Poland.

Liddell Hart suggested that British economic pressure was her best weapon against Germany, with the added use of naval blockade and strategic bombing. In fact, as Germany extended her territories and traded with the East, the naval blockade affected her less and less. Strategic bombing proved a catastrophe, and Liddell Hart’s suggestion that psychological warfare might be the indirect approach that would overthrow Hitler also proved a fiasco.

Such conclusions are not intended to belittle Liddell Hart, but to re-create a time when blitzkrieg seemed impossible, even for a man who had spent his life thinking about it.

World History

World History