While we were still on Matajur, Lieutenant Autenrieth arrived with the battalion order to move to Masseris which lay some twenty-six hundred feet below us. The descent was hard and required the last physical efforts of my dead-tired men. We took the captured officers of the 2nd Regiment of the Salerno Brigade along, for they appeared to be intractable and unwilling to accept their new situation and I did not dare to send them to Luico under a small guard through terrain covered with thousands of abandoned weapons.

We climbed down along a narrow path and reached the charmingly situated village of Masseris in the early afternoon hours without encountering the enemy. The companies were rapidly distributed among the few farms, the most essential security precautions were taken, efforts were made to re-establish contact with the units of the Wurttemberg Mountain Battalion, which had marched ahead in the direction of Pechinie, and then the tired troops rested.

I invited the captured officers to a simple supper. No sparkling conversation graced the board and my guests scarcely touched our modest provender. The gentlemen were too shaken by their fate and that of their proud regiment. I understood their plight completely and did not linger at the table.

My detachment was on the road to the Natisone valley well before dawn. The other units of the battalion had moved forward to Cividale and had a considerable head start. While violent fighting was in progress on the heights west of the Natisone, the Rommel detachment moved down the valley toward Cividale without halts or meals. I rode on ahead and, at noon, came up with Gossler's detachment and the Wurttemberg Mountain Battalion staff near San Quarzo where they were engaged with the enemy, who still held the Purgessino. Lieutenant Streicher and I rode across the battlefield. An occasional burst of Italian machine-gun fire quickened our pace. I met Major Sproesser just east of San Quarzo. My detachment was not committed to action.

Fighting at Purgessimo was over by 1400. After several hours of rest near the northern limits of Cividale—which was in flames— the Rommel detachment moved around midnight into Campeglio from where the remaining units of the Wurttemberg Mountain Battalion were reconnoitring in the direction of Fadis and Ronchis.

Pursuit was resumed in the early hours of October 28. We pushed west. Rain of cloudburst proportions poured down, soaking us to the skin. For a while the men protected themselves against it with umbrellas which the resourceful fellows had “found” somewhere. Soon, however, higher authority vetoed this new addition to the table of basic equipment. We marched on in the streaming rain without encountering the enemy.

In the afternoon, Italian rear guards blocked the road across the swollen Torre River near Primulacco. As a result of the continuous strong rain, the usually shallow brook had become a vicious stream six hundred yards wide. The enemy opposite us shot at everything that moved on the east bank.

We moved down into Primulacco, supplied ourselves with dry things in an Italian laundry depot, and went to sleep. The efforts of the last days and nights had worn us down greatly. An hour before midnight an order came from Major Sproesser: —Rommel detachment, reinforced by a platoon of mountain artillery, must, during the night or at least before daybreak, force a crossing of the stream.” Everybody up! The detachment worked feverishly during the latter half of the night. While the artillery platoon fired several shells on the Italian garrison on the west bank, a footbridge, crossing the numerous arms of the stream, was constructed of all vehicles that could be moved up. The enemy did not disturb the work very much. He appeared to have withdrawn following the impact of the first shell on the west bank. When day broke, the end of our emergency bridge was an even hundred yards short of reaching the west bank, and the enemy had retired.

Lieutenant Grau was the first to ride through the last and very rapid branch of the stream. Since the supply of requisitioned vehicles was insufficient to reach the west bank, a strong rope was stretched across the last section. The riflemen held onto this while wading through the rapid mountain stream, which undoubtedly would have swept an unaided man away. In crossing, an Italian prisoner carrying a large medical kit on his back was torn from the rope by the strong current and, lying on his back, floated downstream. The man apparently could not swim. Besides, the heavy knapsack dragged him down. I felt sorry for the poor devil. Spurring my horse, I galloped after the Italian, and succeeded in getting near him in the stream. In his deadly fear the Italian seized the stirrup and the good horse brought us both safely to land.

The detachment was across within the next fifteen minutes. We moved through Rizzollo, where the people welcomed us very warmly, and Tavagnaco to Feletto, where we joined the other units of the Battalion, which had crossed on the bridge at Salt. Without hostile contact, the battalion moved toward the Tagliamento in the west and reached Fagagna late in the evening. My staff and I drew good quarters. The owners had moved out leaving the house servants behind. We ate and slept.

On October 30, the battalion reached the Tagliamento near Dignano after passing through Cisterna. The local bridge had been destroyed. Strong enemy forces occupied the west bank of the broad and swollen stream and our attempted crossings failed. To the north, we found the roads leading through St. Daniel to the bridge at Pietro completely blocked with Italian columns and vehicles of all kinds. Here, horse-drawn columns, pack-animal columns, and refugee vehicles were wedged in among truck columns and heavy artillery. Vehicles jammed both sides of the road for miles and were so tangled that none could move forward or backward. Italian soldiers were no longer visible. They had sought safety elsewhere. Horses and pack animals had been wedged in for days, and were so hungry they were eating everything within reach, including blankets, canvas, and leather harnesses!

A previously planned night advance of the Rommel detachment across the fields to the bridge at Pietro was unfortunately countermanded by higher authority. We regretted missing some excitement and moved to Dignano where we spent the night.

The next day we learned that a unit of the 12th Division had been mentioned in the army communique as having captured Mount Matajur. This matter was soon corrected at higher headquarters.

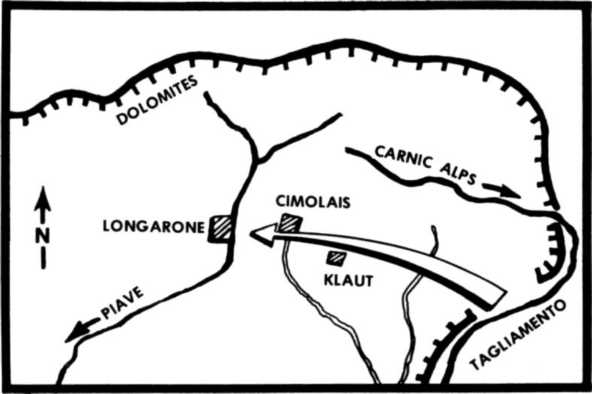

During the succeeding days all attempts to cross the Tagliamento failed. Not until the night of November 2-3, 1917, did the Redl Battalion of the 4th Bosnian Infantry Regiment succeed in getting a foothold on the west bank in the vicinity of Cornino. On November 3 the Wurttemberg Mountain Battalion was detached from the German Alpine Corps and given the mission of breaking through the Carnic Alps, via Meduno-Klaut, as advance guard of the 22nd Imperial and Royal Infantry Division, and of reaching the upper Piave valley near Longarone as soon as possible, in order to block the movement of Italian forces in the Dolomites and prevent their retreat toward the south. (Sketch 61)

The Wurttemberg Mountain Battalion was one of the first to cross the Tagliamento at Cornino. Strong patrols, on captured Italian folding bicycles, advanced to Meduno. Beyond that place, the advance guard of the Wurttemberg Mountain Battalion succeeded in capturing 20 officers and 300 men near Redona. Then we chased the weak Italian rear guard down a narrow path through the wild and crevassed Klautana Alps toward Klautana Pass. My detachment marched with the main body and Gossler's detachment formed the advance guard. It reached Pecolat in the evening of November 6.

Early on November 7, the Wurttemberg Mountain Battalion climbed toward Klautana Pass in its usual formation. The leading units of the advance guard were fired on from the heights near the pass which had an elevation of forty-nine hundred feet. Machine gun and artillery fire also bothered them on the narrow and winding road between Pecolat and the pass (three thousand feet difference in elevation). Italian fire soon interdicted all movement on the road and through the rocky terrain on either side. The enemy, well dug in, sat high up on the perpendicular rock walls of Mount La Gialina (1634) and on the northeast ridge of Mount Rosselan (2067). These two positions were a mile and a half apart and were astride the pass. The position seemed impregnable.

Major Sproesser ordered the Rommel detachment (1st, 2nd, and 3rd Companies and 1st Machine-Gun Company), which was with the main body, to encircle the enemy on the pass by moving south via Mount Rosselan. Even the climb up the Silisia was much hampered by hostile machine guns and artillery and we were obliged to dash from rock to rock. Finally we reached cover from the hostile fire in a lateral valley leading to Hill 942. But soon several hundred yards of Mount Rosselan's high, vertical, rocky walls confronted us and barred further ascent. Encircling the enemy from the south proved to be impossible, leaving a frontal attack against the pass as the alternative.

It took us hours to climb up through the rocks and get at the enemy south of the pass road. The capable riflemen carried the

Sketch 61

The advance through the Carnic Alps.

Heavy machine guns on their shoulders across places where I had trouble getting along without a pack. Not until just before the fall of darkness did my completely exhausted detachment reach the snow-covered knolls seven hundred yards southeast of the pass and established contact with the units of Gossler's detachment lying at the same height some hundred yards north of the pass road. Dwarf pine bushes concealed my men from the enemy, who occupied a semicircular position on the heights immediately to our front.

I gave the exhausted troops some rest and, with Lieutenant Streicher and some scout squads, examined the possibilities for a surprise night attack against the pass. The night was dark with an overcast sky. Fortunately the snow between the low clumps of undergrowth helped somewhat! The crunching of the snow under our feet drew fire from the defenders here and there which at least made it possible for me to determine the disposition of the hostile force.

I managed to locate some suitable machine gun positions about a hundred yards from the pass and at a somewhat higher elevation. It took several hours of careful and hard work to prepare our fire support plans for the attack. I used the entire machine-gun company. At the same time the 1st and 3rd Companies prepared to attack under the fire support of our machine guns from three hundred yards away.

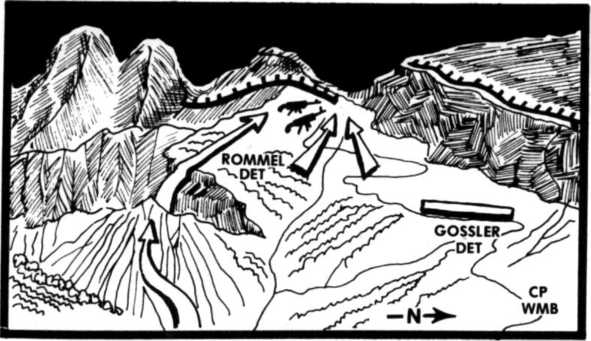

All machine guns of the machine-gun company were to open fire at midnight, and pin down the enemy in the pass for two minutes, and then shift their fire to the enemy on both sides of the pass. The 1st and 3rd Companies were to move up to the right and left of the gully leading to the pass as soon as the heavy machine guns opened fire and take the pass with hand grenades and bayonets. (Sketch 62)

Unfortunately, I stayed too long with the fire-support platoons. When their guns opened up, I was still on the rocky slope some hundred yards from the two assault companies which, to be sure, should have attacked by themselves, but which I wanted to accompany. I rushed forward and, to my astonishment, found the two companies behind their line of departure. Had the leaders failed, or was it the troops themselves? The two minutes of fire for effect by the machine-gun company had passed. The advance movement of the assault troops was no longer synchronized with the fire of the machine gun company and the enemy in the pass was no longer pinned down. No wonder that the attack was repulsed with losses after a hard hand grenade struggle. After the unsuccessful attack, I withdrew both companies to the starting position.

I was very angry at this failure. It was the first attack since the beginning of the war in which I had failed. Hours of hard work had been in vain. A repetition of the attack during the night seemed hopeless and was beyond my dog-tired troops. Their exertions had been such that they needed rest and food before returning to action and neither of these commodities was available in the face of the enemy at an elevation of forty-five hundred feet surrounded by ice and snow. I also questioned the advisability of massing large forces near the pass in daylight. For these reasons, I broke off the engagement. The 5th Company provided security at the pass, as it had done prior to our arrival, and I took my four companies back into the valley near Pecolat. On the way I reported the failure of the night attack to Major Sproesser, whose command post was in a rock fissure halfway up the slope.

We reached Pecolatt before dawn and found the few hovels packed with troops. We camped in the open fields. The pack-animal

Sketch 62

Night attack against Klautana Pass. View from the east.

Detachment came up and the cooks soon brewed plenty of hot coffee which certainly hit the spot. Dawn broke two hours later and as the first rays of the sun caught this narrow valley, I was called to the telephone to receive the following message from Battalion:

—The Klautana Pass has been vacated by the enemy. The Rommel detachment marches without delay and joins the Gossler detachment. The Battalion follows through Klaut.”

Shortly after daybreak, scout squads from the 5th Company had found the pass empty of all hostile elements. The joy of having the enemy yield us such an excellent position without a struggle gave us new strength. The Rommel detachment was soon on the road. In a few hours we reached the pass, this time climbing by way of the road, and were able to observe the fire effect inflicted upon the former hostile positions by the 1st Machine-Gun Company. Evidently, one of the guns had commanded a stretch of the road over a hundred yards long just northwest of the pass and had caused numerous casualties, as the many bloody bandages on both sides of the road bore witness.

Observations: The night attack of the Rommel detachment on the Klautana Pass failed because the combined fire of the machine-gun company and the advance of the assault companies were not synchronized.

World History

World History