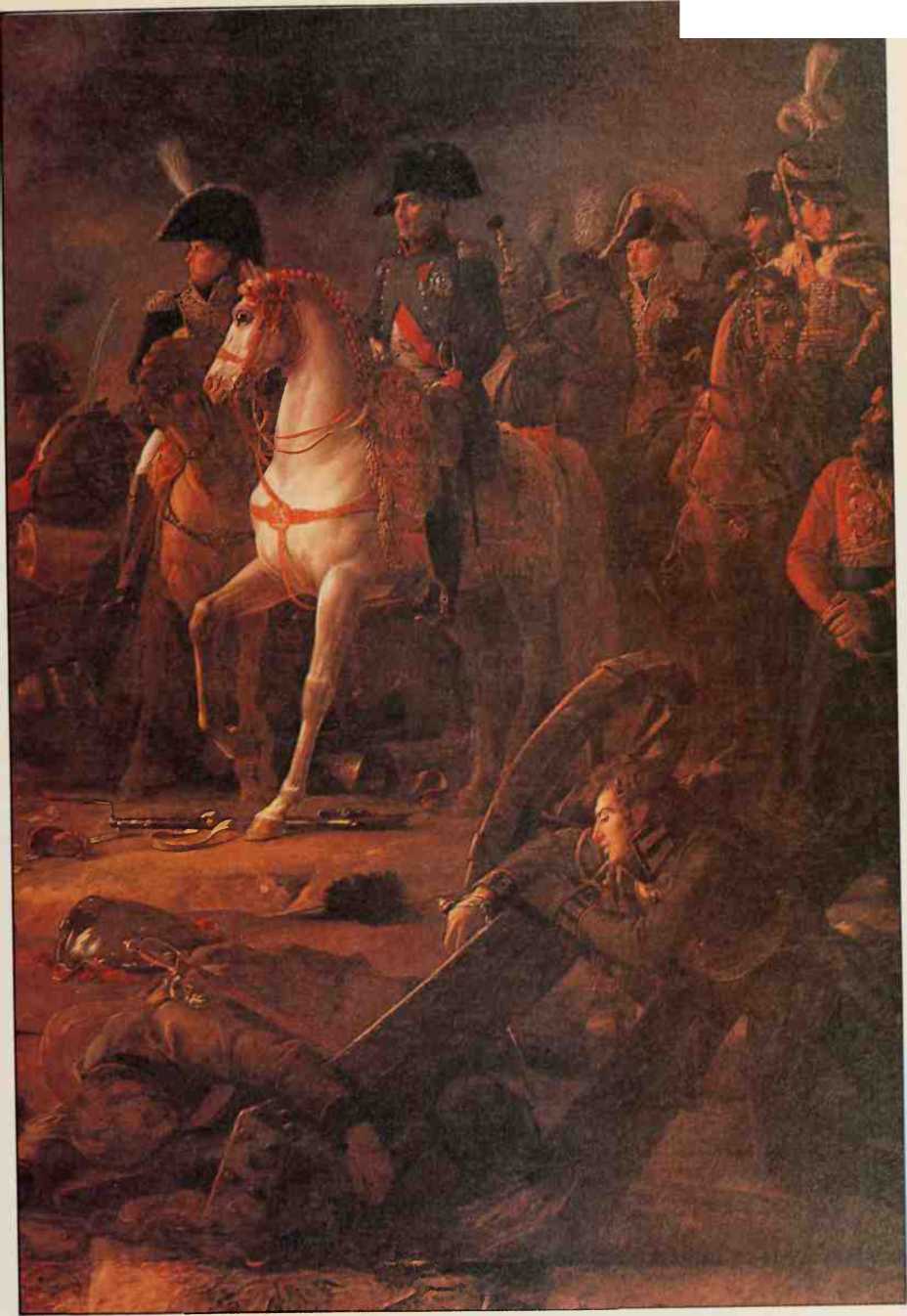

Napoleon at the Battle of Austerlitz (1805) which he regarded as his greatest victory. Unusually for him, it was a defensive battle in which he allowed the Austro-Russian army to attack his right wing so that he could launch a devastating riposte in the centre.

Strategy in war is primarily concerned with the formulation of policy. 'I'his Involves the selection of war aims, the establishment, maintenance or dropping of alliances on a political level, and the application of resources to achieve military objectives. The tactics of a war, on the other hand, are the methods of fighting and manoeuvre employed to secure the immediate objective that is in itself part of the strategic plan. In land fighting, tactics are normally associated with regimental (and below) le’el tasks, although this can depend on circumstances. I’he dividing line between strategy and tactics can become extremely blurred.

The strategy of war has, on the whole, not changed radically through the ages, but tactics, with their greater dependence on methods and means have. Glubb Pasha, the British officer who commanded the Arab Legion noted that: While weapons and tactics may change, terrain and men do not. It could, of course, be argued that terrain can and does change and that man himself has altered over the ages, but one cannot really quarrel with the statement: that ground over which action is fought and the motives, fears and hopes of the combatants have remained essentially unchanged, although weapons and their tactical and strategic deployment have altered as a result of human ingenuity. Indeed, advances in civilization could cynically be identified with man’s growing capacity to kill ever increasing numbers of people by single, less intensive efforts, and primitiveness with man’s inability to kill except at very close range or in hand-to-hand conflict.

D'he physical nature of war has altered radically within the last 150 years, for technological advances in weaponry have produced massive changes not only in the concept of the battlefield itself, but have also led to a widening of the conflict to include the civilian population on a scale never before realized. A soldier who had fought with Caesar in Gaul, for instance, would have had very little difficulty in recognizing his counterpart in Napoleon’s Grand Armee; each fought shoulder-to-shoulder with his comrades in a close-quarter battle. His commanders, 'too, differed little in their approach, with their reliance on infantry, cavalry and supporting arms. Transplant those soldiers to World \’ar I, however, and neither they nor their commanders would have recognized the battlefield, nor indeed what the commanders were attempting. By World \’ar II, battlefield dispersal had become even more marked, although both Caesar and Napoleon may have been more confident with the strategic direction.

Traditionally armies were organized into four basic groups: infantry, cavalry, artillery and the supporting arms, particularly the commissariat. The three ‘teeth arms’ - infantry, cavalry, artillery - had their own part to play, but in battle also attempted to operate together to attain victory. The backbone was the infantry, soldiers operating on foot with their own personal weapons, a firearm and bayonet. Their role was the defeat of the enemy infantry by superior firepower or close quarter action, the conquest and occupation of ground. In addition, they gave close support to the artillery and relied on the guns to destroy physically or morally the enemy infantry, artillery and defensive positions (e. g. fortresses). The cavalry existed to fulfil three basic tasks: to reconnoitre and locate the enemy and pass accurate information back to the commander, to provide a screen behind which the main part of the army could advance or retreat without harrassment by the enemy and, finally, to provide shock on the battlefield in the form of the charge. Secondary functions included the picking off of enemy stragglers and the scouring the battlefield of a defeated enemy.

The ability of the three teeth arms to carry out their traditional roles, however, has undergone considerable change during the last century or so, even though the basic definitions remain unaltered.

The ability of commanders to realize a tactical objective has been greatly hampered by developments, particularly in weaponry, that in themselves have ultimately produced strategic stalemate. Whereas, traditionally, commanders attempted in battle either to split an enemy front in the centre, or to turn either or both flanks, or to encircle an enemy and hence achieve the annihilation of all or a part of its army, by the latter part of the nineteenth century, their ability to do so was largely prevented by technological developments. Tactical success could not be turned into decisive strategic success because the cost of that tactical success was too great in lives and time for its rapid exploitation. This happened mainly because offensive strategic development could be offset by a more rapid defensive deployment by an enemy using exactly the same means and tactics. The climax of this situation came about during the First World War and the deadlock of that war necessitated a fresh tactical approach that restored strategic and tactical mobility.

Historians have generally seen the evolution of modern warfare as stemming from the great political and technological changes brought about by the

A Union 12-pounder field gun battery preparing to fire during the American Civil War. This was the last war in which muzzle-loading smoothbore artillery predominated on both sides.

French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars (1792-1815), and the Industrial Revolution of the nineteenth century. Certainly the French wars introduced into conflict an element of totality - of national as distinct from dynastic struggle, of victory as opposed to marginal territorial gains - that had been absent from Europe since the end of the wars of religion. T he wars in defence of the Revolution had necessitated popular participation in the form of the levee en masse to withstand the seasoned professional armies of monarchical Europe. The French wars drained all countries and after Waterloo most countries would have preferred to revert to small professional armies but for certain developments. After her defeat in 1806 Prussia had introduced conscription, the obligation of compulsory military service for men between 17 and 50 years of age. By this means the concept of a standing army based upon conscription in time of peace was introduced.

And ultimately the other major countries of mainland Europe followed Prussia’s example.

The consequences of such changes were bound to be profound. With larger armies the demand placed upon society itself - financial, industrial, moral - proportionately increased; politically wars became less manageable in that the mobilization of reserves (the essential prerequisite of a nation in arms) inevitably lessened the chances of avoiding wars and also made less likely the prospect of halting, limiting or ending a war once it had begun because of the emotionalism and sacrifice inherent in a national recourse to arms. In their turn larger armies implied a more ponderous tactical deployment plus the prospect of prolonging wars since the availability of reserves could hold off threatened breakthroughs and deny an enemy any decisive initial success. Such was the influence of the growth in the size of armies, made possible by the synthesis of two

Conditions: the first the political will on the part of states to bear the cost and second the development of railways.

Rail was first used for troop transportation in a Prussian exercise in 1846; but the first operational use took place in Italy during the Franco-Austrian war of 1859. Railways simplified the problems of strategic manoeuvrability, supply and the evacuation of wounded, but they were also inflexible and imposed rigidity on their users. While troops arrived at their destination in good condition they were tied to their railhead for supplies and their mobility in the field remained the same as it had been since time began - the speed of animal or human legs. The greater number of troops available meant greater congestion and greater problems of command and control. Thus railways were double edged in effect: they conferred greater strategic mobility (to both sides) but hampered political considerations (by the need to mobilize) and reduced strategic and tactical mobility by putting forces into the field too large to be effectively wielded and tactically slower than an enemy’s strategic deployment capability. Moreover, if the growing ability to concentrate manpower in a given area more quickly than hitherto was lessening tactical mobility, technological developments, particularly in the fields of chemistry and metallurgy, were adding to the problem. And both problems were compounded by an understandable human failure to appreciate to the full the impact of these changes.

I’raditionally the imprecision of weapons dictated the need for close-range fighting between massed infantry (backed by artillery and supported by cavalry) since volume of fire was more important than individual marksmanship. Because of the cumbersome nature of their weapons, the infantry had to load and fire while standing. New w'eapons, however, altered this situation.

Breech loading, rapid-firing rifles for both infantry and artillery opened effective killing ranges, to the immediate embarrassment of a boot-to-boot cavalry charge. The 50-loom (50-100 yard) ranges of smooth-bore muskets increased fivefold by mid-century, while rapid-firing rifles meant a greater volume of fire could be delivered from a soldier in the prone position. In Prussian hands such rifles proved their worth in Denmark (1864) and Austria (1866) while the French in the Chassepot procured a superior weapon that only their strategic and tactical incompetence negated in the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-71. (Repeating rifles, fed by a magazine, were introduced during the American Civil War though they took some twenty years for general adoption in Europe.) Likewise, in artillery, steel replaced bronze and iron, breech-loading rifles smoothbore muzzle-loaders, with the result that the ranges of Napoleon’s time quadrupled. Moreover quickly firing guns mounted on recoil-absorbing carriages enabled gunners to dispense with re-adjustment after firing, while improved explosives and propellants enabled employment of smaller calibres that by definition retained mobility for the artillery.

These developments among others opened battlefield ranges and upset the balance between the three teeth arms. Infantry firepower could shatter a cavalry charge long before the cavalry could close to effective range and an infantry assault could be similarly broken up by artillery before it closed the target. But infantry, entrenched or behind earthworks, had a large degree of protection against artillery. The American Civil War amply demonstrated that entrenched infantry, backed by artillery, could inflict debilitating losses on an attacker - irrespective of colour of uniform. The power of the defence had for the moment outstripped that of the offence. The lessons that might have been drawn went largely unheeded in Europe, in part because three of the most important wars - in the United States, in South Africa and in Manchuria - were far away and could be dismissed as having little relevance to Europe. Von Moltke the Elder, the Chief of the German General Staff, contemptuously dismissed the notion that American events had lessons for Europe; the British were simply not considered as a military factor; and Alanchuria and the Russian experience could be put down to extreme local factors. Certain concessions to reality were made however; the Russian experience in 1877 outside Constantinople showed the necessity of digging in under fire because of

The heavy losses incurred in frontal assault on even field fortifications: infantry tactics necessitated a thinning of an advancing wave into an extended skirmishing line with the fire fight being won at ranges between 400 and 6oom (400 and 600 yards). Infantry advanced by waves in depth until fire supremacy had been achieved before the final bayonet assault was launched from ranges of about loom (100 yards). The British cavalry for a short time after South Africa carried a carbine (a short barrelled rifle) but subsequently reverted to lance and sabre as did other armies who experimented with machine guns to add to the power of their recce forces. But for the most part the lessons were missed: the Polish banker Ivan Bloch, predicted in 1911 that a future major war would be a terrible war of attrition in

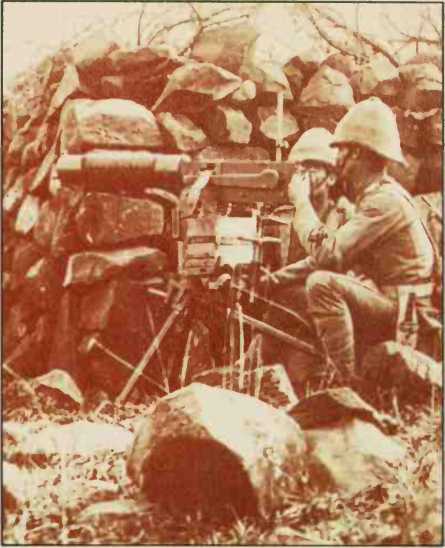

Right: The Maxim gun was the first effective machine-gun to be used in action. It is seen here with a British crew during the Boer War in South Africa. Of all weapons in the 20th century the machine-gun has had the greatest impact on land and air warfare. Below: An i8-pounder with its British crew during the First World War.

Which defence would predominate. Such a war would be a lingering trial of strength, involving all the physical and moral resources of the combatants, only to be resolved when the strain proved too great for one of the sides. Most people tended to dismiss such observations. 'riie reality of war was distant in Europe by the turn of the century: nationalist propaganda, in all countries, in stressing what were regarded as national traits, came to place moral factors as the supreme consideration in the pursuit of victory. Elan and the imposition of moral authority, a heady and romantic concoction assumed a greater importance than detailed consideration of the effectiveness of defensive machine guns. The process of disillusionment was to take four bloody years to complete.

World History

World History