ORLD War II TRIGGERED sweeping changes in warfare. Motorized personnel carriers sped troops to the battlefront. Improvements in aircraft design led to aerial bombing and the use of paratroopers. Rockets and missiles came into use. And, at war’s end, the atomic age dawned.

The use of propaganda as an important weapon was another change. All the major powers used propaganda, not only to influence the thinking and actions of their enemies, but also to stimulate desired behavior among their own citizens. .

In Germany the Minister of Propaganda, Paul Joseph Goebbels, was elevated to a position second in rank only to Hitler himself. In Great Britain the head of the propaganda agency held cabinet rank. The United States established a propaganda agency called the Office of War Information, the OWI, for short. It was headed by Elmer Davis, a well-known

Journalist of the time.

The chief weapons used in the “war of words” were the leaflet, the loudspeaker, and the radio. A special military organization, the Psychological Warfare Division, was created to use these weapons.

The soldiers who staffed what came to be called the “psywar units” were unlike any soldiers ever known before. Instead of guns and ammunition, they were equipped with typewriters, portable printing presses, public address systems, and radio transmitters. They would arrange for massive leaflet airdrops over enemy positions. Or they would rig up loudspeakers, some with amplifying equipment that would carry sound for a mile or more, and call out messages to enemy soldiers in an effort to entice them to surrender.

On D-Day, Alhed aircraft dropped more than 27 million leaflets on enemy positions along the invasion coast. A survey taken during the summer of 1944 disclosed that 90 percent of the German soldiers taken prisoner had propaganda leaflets in their possession.

Experts classify propaganda in three types— white, gray, or black. In white propaganda, no effort is made to conceal the source. An American propaganda leaflet urging German soldiers to surrender obviously originated from an American source. Tokyo Rose’s broadcasts from Japan to American troops in the Pacific during the war is another example of white propaganda.

Gray propaganda revealed no source at all. When prepared by American psywar specialists, it usually took the form of newspapers or news-bearing leaflets

LOUDSPEAKER ON AMERICAN LIGHT TANK IN ZERBET, GERMANY, WAS USED TO TELL PEOPLE THE TOWN HAD FALLEN TO THE ALLIES, AND TO ORDER THE END OF RESISTANCE. (National Archives)

That were dropped over enemy positions. German soldiers had little doubt as to where the newspapers had originated, but they were so hungry for news they read them anyway.

Black propaganda was the most malicious. It pretended to originate from the enemy’s own sources. One example was the small booklet prepared by Americans and distributed to German troops. It looked like an official German government medical handbook, giving information and advice on how to self-treat minor ailments and injuries. But the book’s actual purpose was to instruct soldiers how to pretend to be ill and get themselves excused from active duty.

Radio was often used to spread black propaganda. Programs originating in England pretended to be

German stations broadcasting to the German people.

The man in charge of the Alhes’ black radio operation was Sefton Delmer, a British journalist. He had been born in Germany of British parents and, because he had lived in Germany as a young boy, he spoke German as well as he spoke English. During the 1930s Delmer lived in Berlin and worked as the Berlin correspondent for a London newspaper. The Daily Express. He knew many of the Nazi leaders personally.

To staff his station, Delmer scoured the German prison-of-war camps in England, seeking those prisoners who held anti-Nazi behefs. He also obtained broadcasters and scriptwriters from among German men and women who had immigrated to England in the months just before the outbreak of war.

Delmer and his staff read German newspapers to keep abreast of what was happening in the principal German cities. They monitored conversations of German prisoners, not merely for information, but to pick up the latest slang. Delmer cautioned his staff to use the term “We Germans’’ in their broadcasts instead of “You Germans.”

So that the broadcasts would be behevable, Delmer had to make the programs sound even more patriotic than official German radio broadcasts. So he never failed to broadcast Hitler’s speeches. He called for vigorous efforts on behalf of the German war effort. He constantly referred to American and British bombing planes as “terror raiders.”

Once he had estabhshed credibihty for his operation, Delmer began to slip in propaganda messages in a crafty manner. For example, an announcer

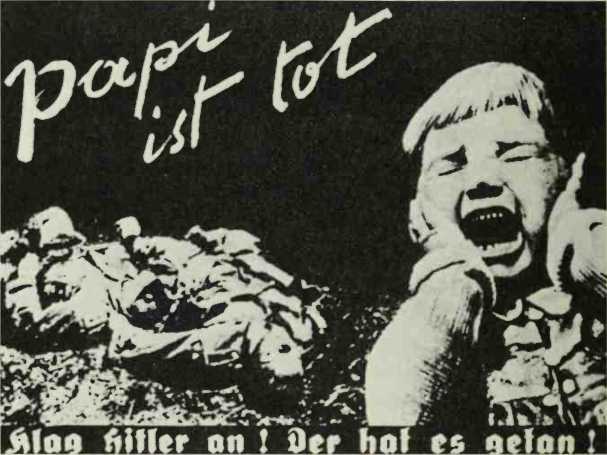

THIS PROPAGANDA LEAFLET WAS DISTRIBUTED TO GERMAN FAMILIES BY THE RUSSIANS DURING WORLD WAR II. THE CAPTION READS: “DAD IS DEAD! ACCUSE HITLER! IT’S HE WHO DID IT!” (New York Public Library)

Would follow a report on the situation on the Russian front with the observation that, “It doesn’t matter that 500 of our soldiers were killed in battle—or even 5,000. What is important is that we have a victory to present to our Fuehrer on his birthday.” Such statements weakened the trust and confidence of German people in their leaders.

Sometimes Delmer created a rumor by denying it. In 1943, when German troops were being transported by air to North Africa to blunt an Alhed thrust, Delmer beamed a black radio broadcast to German soldiers denying reports that transport planes were unsafe. “It is perfectly true,” the broadcaster declared, “that there were some tragic incidents a while back when some planes crashed on taking off.

But the defect has been corrected/’ German soldiers boarding transport planes must surely have been shaking in their boots.

German sailors were also the target of black radio broadcasts. Early in the war German U-boats prowled the Atlantic, seeking to destroy allied shipping. German submarine crews at French ports were beamed broadcasts in which servicemen complained of glory-seeking U-boat commanders who were condemned for taking their submarines and crews on foolhardy missions mainly to earn promotions and awards for heroism. This placed doubts in the minds of the German submariners as to the leadership qualities of their commanding officers.

A LEAFLET BOMB FOR USE WITH A P-47 THUNDERBOLT. (National Archives)

Delmer’s broadcasts often sought to undermine the authority of Nazi Party officials. He invented stories to demonstrate how they used their Party jobs for personal advantage. In one such broadcast, he told how the wives of Party officials (whom he named) in the town of Holstein learned from their husbands that the country’s entire textile output was going to be needed for the war effort. The women immediately rushed to local department stores and bought up all available articles of clothing.

The broadcast caused the German commonfolk to question the conduct of their leaders. At the same time it implanted in their minds that a severe clothing shortage loomed.

Hitler realized that the radio broadcasts could seriously damage the morale of the German people. He ordered the broadcast channels to be jammed with static and interference, but the messages still got through. Hitler decreed that anyone who hstened to the illegal stations would face imprisonment or death and he planted a rumor that a secret invention could detect those who listened to them.

At one stage German propagandists attempted to send black radio broadcasts to the United States. The programs featured two plain and simple midwesterners, Ed and Joe. They explained the poor quality of their broadcasts by telhng audiences that their transmitting facilities were located in a trailer and that they had to niove from place to place to elude the FBI. The broadcasts actually originated from the German port city of Bremen.

Ed and Joe often spoke out against President Franklin D. Roosevelt, condemning him as “that

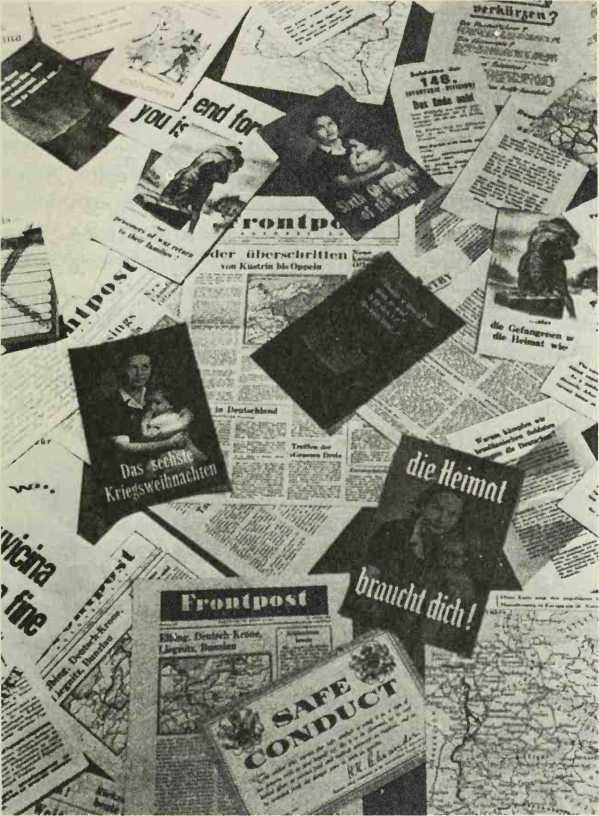

PROPAGANDA LEAFLETS PRINTED BY THE ALLIES FOR DISTRIBUTION TO GERMAN TROOPS AND CIVILIAN POPULATION. (National Archives)

Goof Roosevelt,” but the broadcasts had little be-lievability and listeners often laughed at what was meant to be serious.

Delmer was more successful, but sometimes his broadcasts did not have the effect he intended. In an effort to give his programs an authentic German flavor, he often played songs that had been recorded in German by Marlene Dietrich, a well-known American singer who had been born in Berlin. After the war Dietrich was accused of having sung for the German people over German radio stations. The charges angered her and she denied them heatedly.

People in Germany, however, insisted they heard her. They did not know, of course, that Dietrich’s songs were part of Delmer’s programming. And it was not until long after the war that Dietrich herself learned what was behind the accusations.

Other of Delmer’s broadcasts came back to harm the Alhed cause. One of his continuing goals was to paint local Nazi officials as corrupt or traitorous, and he would identify these officials by name and position.

After the war when some of these same officials were being tried as war criminals, they used Delmer’s broadcasts as their defense. Delmer had declared that they were traitors, that they were helping to bring about the defeat of their nation. “That’s right,” said the accused war criminals, “that’s exactly what we did.” By claiming to have supported the Allied cause, they hoped to be declared innocent and escape punishment.

Delmer realized that in some instances there was no predicting the effects of his broadcasts. As he once observed, black radio could sometimes be a “black boomerang.”

World History

World History