There was a third alternative: for the Allied Army to advance and meet the invading Germans in Belgium. This is the plan that was adopted. As well as ensuring that France’s industrial and mining areas along the frontier were well behind the lines, it would deny the Luftwaffe advanced airfields for attacks upon Paris and London. But where in Belgium? The Belgians had already cashiered their Chief of the General Staff for closing the barricades on the Belgian frontier during an invasion scare on the night of 13 January 1940 and followed this with an apology to the German ambassador for this unneutral act. The French and British commanders had never even met their opposite numbers in the Belgian Army, let alone staged military exercises with them. No fronts had been allotted to the various commands. There were no prepared communications, no lines of supply or ammunition dumps of any kind available for the British and French armies. All of this would have to be worked out after the Germans struck. When the Allied armies reached their defensive positions, they would have to build their own fortifications.

With the Allies facing such a monumental task, it is tempting to say that they would have done better to build and man a defense along the Franco-Belgian frontier and wait there for the expected German attack. But this would have granted the Germans air and sea bases along the Channel. It would also have resulted in the Franco-British armies sitting behind a defense line watching Belgium’s twenty-division army locked in battle with the Germans. Whichever way the Allies played it, it was going to be a mess, a mess stemming directly from the Belgian refusal to cooperate for their own defense. The ultimate expression of this attitude came when the Belgian ambassador in London, some hours after the Germans had invaded his country, made an official diplomatic protest that the British armies had crossed the Franco-Belgian frontier to fight the invaders without having received an official invitation to do so.

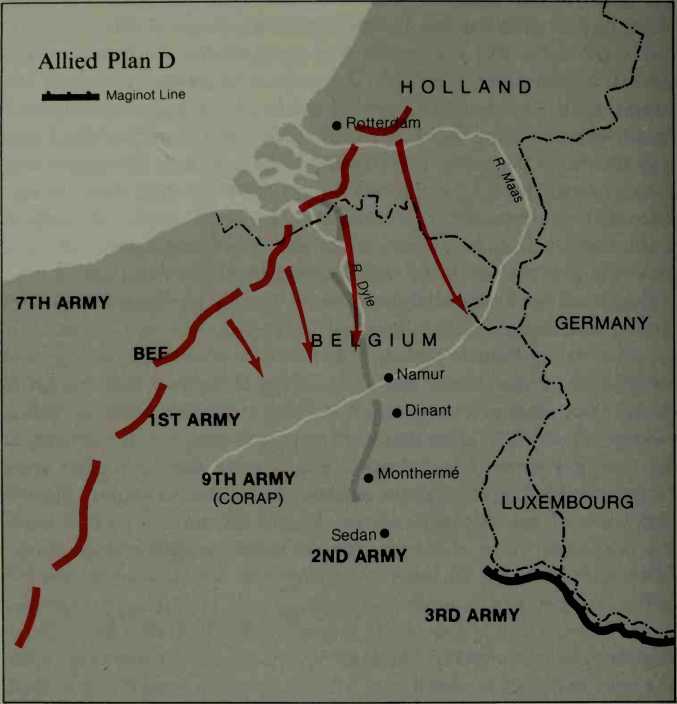

The Anglo-French plan to move armies to a defense line that followed the rivers Meuse and Dyle—Plan D—meant that the whole Allied force must pivot upon the 9th French Army of General Andre-Georges Corap. The army that was to perform this complex movement was not only spread more thinly along its front than any other army but was far below strength in antitank and antiaircraft guns. It was also short of the transport needed for the movement, so that when the time came, most of the men had to march to their new positions. Some units marched 75 miles, a grueling task for an army on the eve of battle, especially an army comprising mostly middle-aged reservists.

It was of a unit in this vitally important Ninth Army that a British inspecting officer wrote, “Seldom have I ever seen anything more slovenly and badly turned out. Men unshaven, horses ungroomed, clothes and saddlery that did not fit, and complete lack of pride in themselves or their units. What shook me most, however, was the look in the men’s faces, disgruntled and insubordinate looks, and although ordered to give ‘Eyes left’ hardly a man bothered to do so.”

Inactivity, propaganda, and drink have been cited as the three main causes of demoralization of the French Army in 1940. Drunkenness among the soldiers during the months of inactivity had caused the railway authorities to arrange for sobering-up rooms to be available at big railway stations. However, there were many first-rate French divisions with high morale and first-class equipment. The low standard of the reservists was more indicative of the extent of France’s mobilization—one man in eight—than of the state of its regular army formations.

The French had called up so many men that they crippled their industrial production. Consequently, skilled men had to be released from the army, causing not only new disruption but a lowering of

The advance of Anglo-French armies from the French border to meet a possible German attack along a line in central Belgium. Note the way in which General Corap’s 9th Army has to advance and bend its left wing and make a stand along the western edge of the Ardennes Forest. This army of weak reservist divisions was to be in the path of the panzer attack through Luxembourg. The Allied armies were to move into position along the Meuse, from Sedan to Namur, and northward along the river Dyle, which gave the plan its initial.

Morale among men who were not released. Their discontent was fomented by the lack of military equipment and of any training for modem war. The British mobilized only one man in forty-eight, but war production had not yet properly started there. On what was now being called the “home front,” vast numbers of engineers were still looking for jobs, and there was a total of 1.5 million unemployed.

The British Expeditionary Force (B. E.F.) in France was tiny, but it was entirely motorized. General Bernard Montgomery, then commander of the B. E.F.’s 3rd Division, said of it, “The transport was inadequate and was completed on mobilisation by vehicles requisitioned from civilian firms. . . they were in bad repair and, when my division moved from the ports up to its concentration area near the French frontier, the countryside of France was strewn with broken-down vehicles.”21

Montgomery says the entire British Army was unprepared for a realistic exercise, let alone a real war. The B. E.F. had Britain’s choicest military equipment, but it had not been possible to put together an armored division to include in it. The British antitank 2-pounder guns were in short enough supply to prompt the hasty purchase of 1-pounder guns from the French. They were mounted on handcarts. There were no heavier antitank guns and very few light antiaircraft guns. But in Britain, the Secretary of State for War proudly told the nation that the B. E.F. was “as well if not better equipped than any other similar army.” •

The French Army depended for the most part on horse-drawn transport. No doubt it seemed logical that those French units given motor transport should be on the outer rim of the Plan D movement on the Dyle River, for they had farthest to travel. The British held the central part of this moving front, while Corap’s aforementioned unfortunates were the pivot.

There was no strategic reserve. France’s only three armored divisions were in the rear areas, rather than part of the front, simply because they were still undergoing their initial training.

World History

World History