Alone among Union generals. Grant had been genuinely successful. Lincoln placed him in charge of all Union armies early in 1864.

On the Move. The union commander planned out his strategy: Federal forces would make four moves against the Confederate field armies. One Union army would attack up the James River toward Richmond. Another would advance from Harpers Ferry up the Shenandoah Valley to capture this Rebel breadbasket. From Chattanooga, Sherman would march on the rail and industrial center of Atlanta. Grant himself would join Meade for a showdown in Virginia with Robert E. Lee.

Lee’s strategy was also a simple one. Since he was outnumbered, he would try to entice Grant into attacking into the teeth of the strong Confederate defenses. Lee hoped he could fight Grant to a bloody draw, inflicting so many casualties that the North would weary of the war’s high human cost. If Lincoln were defeated in the upcoming November elections, Lee believed the new government might finally let the Southern states leave the Union in peace.

The Wilderness. George Meade’s Army of the Potomac, with Grant directing its movements, crossed Virginia’s Rapidan River on May 4, 1864. Grant hoped to march quickly through the tangled, scrubby forest known as the Wilderness, site of the 1863 Union defeat at Chancellorsville. The Union soldiers camped amid the skeletons of those who died in that battle. Their bones had been washed from shallow graves by winter rains.

Lee aimed to catch Grant’s 100,000-strong army in this Wilderness. Here the Yankee advantage in numbers—Lee had just 60,000—would be offset by dense woods.

On May 5, Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia struck at Grant out of the tangled thickets. The Federals threw them back and counterattacked, but no general, not even Grant, could control an army in such a dense forest. The smoke from a hundred thousand rifles blanketed the thick underbrush, and muzzle flashes in the murk often were the only signs of the enemy.

Veterans remembered the Wilderness for the continuing, deafening roar of musketry—it overwhelmed orders, battle cries, and the screams of the wounded.

Soon, the heavy gunfire and shelling set the dry leaves and brush ablaze on the forest floor. The wounded

In every battle, gray and blue soldiers were left behind, cut off from friendly units or surrounded by enemies in the confusion of battle. If they were unlucky, they wound up as prisoners of war.

Occasionally, whole garrisons surrendered together. At Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, in 1862 during the Antietam campaign. Stonewall Jackson surrounded and captured

12.000 Union troops. Ulysses S. Grant took the “unconditional surrender” of more than

12.000 Confederates at Fort Donelson in Tennessee. All of these men were marched to prison camps. North and South.

Until 1864, these men were held for only a few months before being exchanged. Because most prisoners were held for only a short time, both sides failed to devote much attention to the care of prisoners. In Northern camps, the harsh weather, crowded conditions, and lack of blankets and shelter made thousands of Rebel prisoners sick. At Rock Island, Illinois, 1,800 Confederates died of raging smallpox. In Maryland, at Point Lookout, Rebel prisoners were reduced to catching rats to fill the gaps left by meager rations.

The prisoner exchange system broke down in early 1864, when Confederate authorities refused to free captured black soldiers in exchange for Southern soldiers. Instead,

Captured blacks were returned to slavery in the South. General Grant ordered a halt to prisoner exchanges.

The Southern camps were, in many cases, not much worse than those up North. But food shortages in the South made conditions very harsh for Union prisoners, especially toward the close of the war. Two camps were particularly infamous. Belle Isle, a muddy pen in the James River in Richmond, was a deathtrap for thousands—90 percent of the survivors weighed less than 100 pounds.

Even worse was Andersonville, in Georgia. Designed for 10,000 prisoners, by August 1864 the stockade held 33,000 Yankees. Diseases, malnutrition, and lack of medical care killed them by the thousands. One day saw Union boys dying at a rate of one every eleven minutes. By war’s end, 13,000 prisoners had been buried in Andersonville’s mass graves.

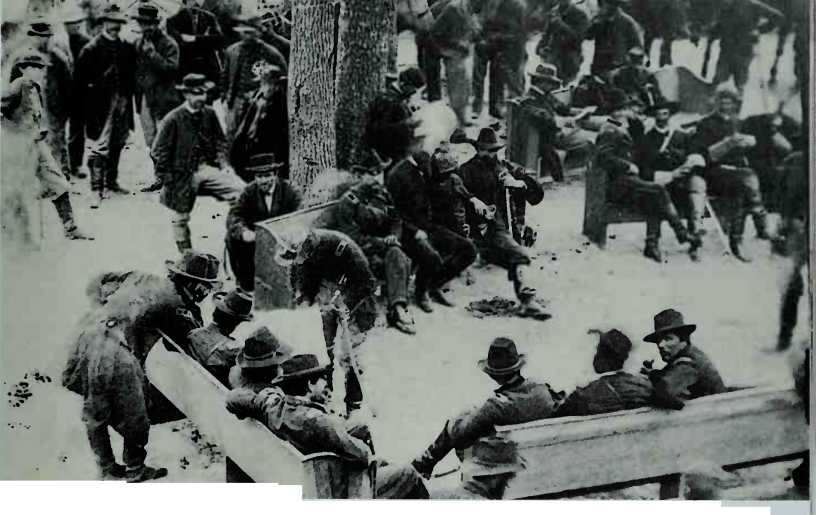

Getieral Grant (leaning over bench) consults a inap with officers. He now had a hold on Lee’s anny and would not let go.

Who were able crawled desperately to escape the flames. The rest suffocated or burned to death. In the choking smoke and growing darkness, the two annies grappled for position and a little sleep before dawn reignited the fight.

Hancock’s Charge. The ne. xt morning. Union General Winfield Scott Hancock, who had turned back Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg, drove deep into Lee’s right flank. The Yankees were within sight of Rebel supply wagons. Robert E. Lee was standing in his stirrups, trying to rally his men at a small farm clearing. For a moment it looked as if Hancock’s men would break Lee’s army, but Longstreet came up with reinforcements just in time.

Lee tried to lead the Texas Brigade into the fight personally, but the men refused to go in unless Lee pulled himself out of danger. "Lee to the rear! Go back. General Lee, go back! We won’t go unless you go back.”

Then the Texans charged and drove Hancock’s troops back into the thickets. Soon the Yankees were backed up to their own log breastworks, hanging on against the Rebels while the wooden barricades caught fire from the burning underbimsh.

Late in the day, Longstreet and Gordon swept out of the Wilderness on both of Grant’s flanks, smashing the Union lines on left and right. Only darkness and the accidental wounding of Longstreet (shot by his own men, like Stonewall Jackson the year before) kept Grant’s army from defeat at Lee’s hands.

No Retreat. In two days of confused but savage fighting, Grant’s army lost 17,600 men, more than twice Lee’s casualties. The Union toll of killed and wounded was

“Whatever happens, we will not retreat.’’

— Ulysses S. Grant

In a message to Lincoln

Worse than either Fredericksburg or Chancellorsville. But Grant, with 100,000 men, knew he could absorb such losses. Lee could find no replacements.

In the past, the Army of the Potomac would have retreated after such a savage fight to refit and regroup. But this was a new commander. On the evening of May 7, Grant started his army not north but south, in a move out of the Wilderness and around Lee’s right flank. The Union soldiers knew what this meant—they were not turning back. "Our spirits rose," one soldier recalled. "We marched free. The men began to sing.”

World History

World History