It was Friday 13, February 1942 and I was watching the sun rise from my Command Post on top of Mount Faber, Singapore. The rays from the red orb of the sun radiated in ever widening shafts of red; just like the old ‘Rising Sun’ flag of Japan used to be.

I remember that I was feeling pretty gloomy at the time but this evil omen gave me an uncomfortable sense of impending doom. Singapore at that time was obviously in its death throes and there seemed to be very little future in it. The Japanese Army had driven right down the length of Malaya and the city was closely besieged by a ruthless and efficient enemy.

About midnight the following night, a signal came from HQ at Fort Canning saying an unidentified ship had been located just outside the minefield covering the entrances to Keppel Harbour and that no British ship was in the area. I was at that time second-in-command of the 7th Coast Artillery Regiment covering Keppel Harbour with its powerful armament of 15-in, 9.2-in, 6-in and a host of other smaller weapons. There was another similarly equipped regiment defending the Naval Base at Changi. I rang up the Port War Signal Station, our line with the Navy, which was manned by sailors. There was no reply and we discovered later that it had been evacuated but for some reason no one had informed us.

I then ordered the 6-in batteries at Serapong, Siloso and Labrador to sweep the area with their searchlights. Almost immediately a ship

Which seemed to be of 8,000 tons was illuminated at a range of 7,000 yards, just outside the minefield. We challenged the ship by Aldis lamp but the reply, also by lamp, was incorrect.

Fonunately, in order to assist in this sort of situation, the Navy had posted an excellent rating who was standing by my side. We had a copy of Jane's Fighting Ships and the rating pointed to a photograph of a Japanese landing craft carrier and said, ‘I reckon that’s it, sir.’ I gave the order ‘Shoot’ and within seconds all six 6-in guns opened up with a roar. The guns had been permanently sited, and even without radar, which had not been installed, their instruments and range-finding gear were so accurate that preliminary ranging was unnecessary. Direct hits were scored at once. Flames, sparks and debris started flying in all directions. The crew could be seen frantically trying to lower boats but it was all over in a matter of minutes, after which the ship just disappeared into the sea.

This action was reported to Fort Canning but it is strange that it has never, so far as I know, been mentioned in an official account. Most likely the record was lost together with a good many other documents in the subsequent events after the surrender of Singapore.

Next morning we were ordered to fire the guns at the very large number of oil tanks situated on the islands around Pulau Bukum about 3.5 miles from Keppel. Something like 200,000 tons of oil were set on fire. After that we were ordered to blow up all the guns. This was achieved by placing a charge of gelignite in the breech of each gun and another in their magazines. Time fuses were lit and the resulting explosions were pretty impressive.

Singapore in its death throes has been described in all its harrowing details by a good many writers. It is not a pretty story but the overriding factor of which everyone was painfully conscious was that the supply of water had just about dried up. In fact, troops were having to break into houses to get at the water remaining in the cisterns.

On the evening of 15 February, the gunners manning the Command Post on Mount Faber had been joined by a small Indian Commando unit and were holding a line across the main road near Keppel Golf Course below Mount Faber. At about sunset we distinctly heard Japanese troops fanher up the road shouting ‘Banzai!’ ‘Banzai!’ ‘Banzai!’ Shortly afterwards orders were received from Fort Canning that we were to cease fire and we were informed that the great fortress of Singapore had surrendered. The Coast

Artillery had done its best and the fact is that the power and efficiency of its armament had the effect which it was designed for. It was exceedingly unlikely that the Japanese naval forces would be so rash as to make a frontal attack on Singapore because it is doubtful if they would have survived the encounter.

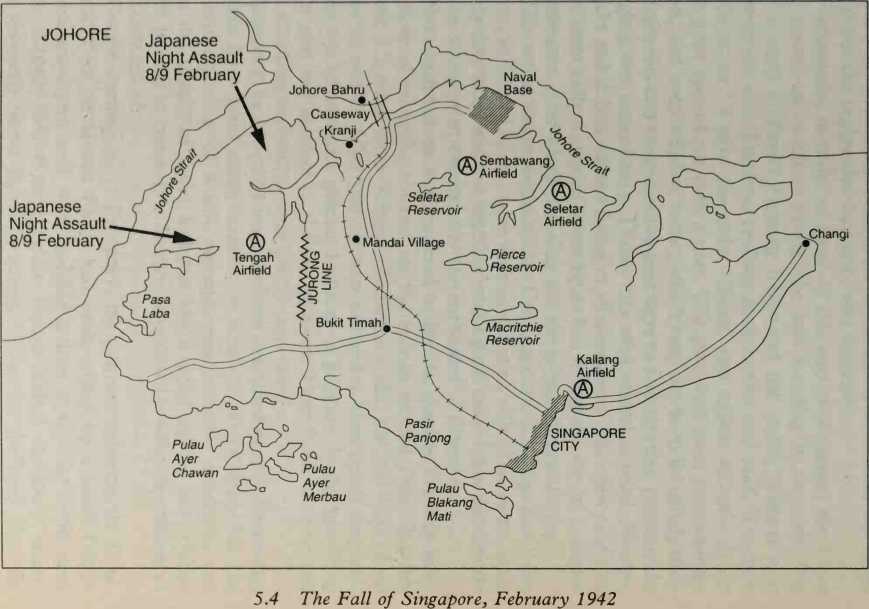

The plans for countering the expected invasion of Malaya by the Japanese were based on this factor and they were well conceived. The 11th Indian Division was poised on the frontier of Malaya and Thailand in December 1941, and Operation Matador was to send 11th Indian Division into Thailand and occupy the beaches at Singora and Sungei Patanie before the Japanese landed. British officers dressed in plain clothes and riding bicycles had been sent into Thailand to reconnoiter the area, where they met Japanese officers doing precisely the same thing. Air reconnaissance had reported large numbers of Japanese transports heavily escorted by warships and yet Operation Matador was called off for political reasons. So we got off to a bad start and our troops were caught on the ‘wrong foot’. It soon became apparent that Japanese methods of warfare were totally different from ours and we had an awful lot to learn.

Part of my job was to direct the fire of the coast guns on to landward targets. It was mostly harassing fire, sometimes at the request of the Army and sometimes at targets picked at random, such as likely landing places on the north and west side of Singapore Island. There was no possible means of observing and correcting the fall of shot at

27,000 yards (15.3 miles) or more, so what the results were, goodness only knows. The only live Japanese I saw was a little perisher perched on top of a telescopic mast where he was probably spotting for his own guns. He was about three miles from where I was watching with my binoculars and just behind the grandstand of the racecourse near Burkit Timah. I turned the Connaught 9.2-in battery on to him and fired about 30 rounds. The little man disappeared in a cloud of smoke, dust and debris most of which came from the grandstand. Coast Artillery was not designed for this job but it certainly made a lot of noise, particularly the 15-in guns, whose flashes at night were quite spectacular. It was all a matter of firing at map references and hoping for the best.

I am anxious to dispel the myth that the Coast Artillery did not turn round and shoot at the enemy, so I propose to deal with each of the main batteries in turn.

The searchlights were manned by locally enlisted Malays who

Deserted overnight the day before the surrender. They just vanished - with one exception. He was a half-caste whom we promoted to Bombardier because he spoke English and Malay fluently and was very useful. He stayed and the curious thing is that he reported to me a month later in Colombo (Ceylon) and asked me if he could be sent back to Malaya. Intelligence grabbed him, gave him a course of training and, eventually landed him with a wireless set on the coast of Malaya. I hope he survived.

The following is an account of the actions of the Coast Artillery batteries.

Faber Fire Command

Pasir Lxiba Bty. Fired at the Japanese crossing Johore Strait in boats but the battery was a sitting duck for the Japanese who brought up mortars and lobbed bombs from concealed positions until the battery was put out of action. The guns were blown up and the detachments withdrew.

Buona Vista Bty. When Vickers installed the two 15-in guns in 1938 they fitted Magslip cables that were too short for all-round traverse. These cables carried an electric impulse from the Plotting Room to actuate the dials on the gtms. The result was that stops were put on the traversing arcs of the gtms which prevented them from pointing inland. The Japanese broke into the battery area but were driven out by the gunners and Australian infantry. The guns were then blown up and the personnel marched to Mount Faber and next day were attached to an infantry battalion with their battery CO Major Phillip Jackson.

Siloso and Labrador Btys. Both batteries fired a good deal of HE at Japanese troops advancing along the coast road through Pasir Panjang. It was reported to me by an infantry sergeant that the guns had caused a lot of Japanese casualties.

Serapong and Silingsing Btys. Owing to hills and buildings, they were not well sited to fire inland and I do not know whether they actually fired or not. It is possible that they fired counter-battery programs.

Connaught Bty. The three 9.2-in guns fired a considerable amount of ammunition including all their 90 HE rounds. Targets which I know were engaged included Johore Bahru, right across Singapore Island, where the Japanese had their HQ, possible landing places on

The south bank of Johore Strait, a tank attack on the Bukit Timah road, Tengah Airfield, Jurong road and the Japanese artillery spotter already mentioned. Also counter-battery programs.

Changi Fire Command

Most of the action took place on the western side of the island. It is difficult to obtain accurate information on this Fire Command but it is obvious that the guns could only in many cases have been fired at extreme range.

Johore Bty. I do know that the three 15-in guns fired a great deal of their AP ammunition, notably at Johore Bahru and the reservoir area. They had all-round traverse but they had to knock down some of the concrete emplacements in order to get the shields round. Colonel Masanobu Tsuji, Chief of Staff Japanese Twenty-Fifth Army (Lieutenant General Tomoyuki Yamashita), records coming under their fire on the newly captured Tengah Airfield (11 February). Abandoning his car, he was blown into a ditch and watched the 50-ft-wide shell-holes appear around the drainage pipe he crawled into.

Tekong Bty. The three 9.2-in guns fired at several targets including the 400 Japanese landing on Pulau Ubin island.

Counter Battery An organization was hastily set up with OPs (observation posts) on the tops of high buildings such as the Kathay Building and other places. Bearings of enemy gun flashes were fed into an operation room, probably in Fort Canning.

There must have been plenty of enemy batteries to neutralize. The Japanese did not make great use of their artillery in their advance through Malaya, relying mostly on their infantry guns and mortars which they were very expert at handling. For the final assault on Singapore Island they deployed a very large concentration of artillery which they managed somehow to transport all the way down the peninsula. Japanese Army engineers excelled in repairing broken bridges. They brought up a considerable amount of heavy artillery which, judging by the effect of their shells, must have been up to 6-in caliber. Their preparatory bombardment (from 440 guns) before crossing Johore Strait was almost of First World War proportions.

One was constantly aware that once the small supply of HE was used up the guns could only fire armor-piercing (AP) projectiles.

These are made with very thick, hard steel walls and nose, designed to penetrate the thick armor-plate of a warship without collapsing. They have a delay-action fuse fitted to the base of the shell. The effect is that the shell detonates inside the ship and, as the quantity of ammatol or lyddite explosive is comparatively small, due to the thickness of the walls, the shell casing breaks up into very large chunks of steel. These smash up boilers, steam pipes, electric cables and machinery and generally create havoc inside the ship. As a man-killing instrument of warfare AP ammunition is not very effective. I expect the shells with a high angle of descent drilled a hole about 20 ft deep and there was none of the fragmentation which is essential for antipersonnel requirements.

It is interesting to indulge in that well-known pastime of hindsight and wisdom after the event. The lessons of Singapore were learnt and applied with considerable urgency in Ceylon. Colombo and Trincomalee were the last remaining bases for the Royal Navy in the Far East and were vitally important. The following measures were taken and, had they been applied in Singapore, it is reasonable to suppose that the Coast Artillery could have been more effective.

1 The post of C-in-C and Governor-General was created and ably carried out by Admiral Sir Geoffrey Layton. This ensured there was little likelihood of politics rearing its ugly head and cramping the style of the Service Chiefs in the way that it did in Malaya. The atmosphere in Ceylon was electric - ‘There is not going to be another Singapore here.’

2 Both Colombo and Trincomalee had quite powerful Coast Artillery of modern 9.2-in and 6-in guns. All guns were given all-round traverse and overhead cover against air attack.

3 Each Fire Command was given an armored, tracked vehicle which was fitted with a No. 19 wireless set, to act as a mobile OP for co-operation with the field army.

4 Permanent OPs were established round the perimeter of each port. These OPs had a permanent telephone line to an operation room.

5 Each coast bty had its own 40 mm Bofors AA gun manned by coast gunners.

6 Each Fire Command had on its establishment a fully equipped eight-gun 25-pounder field battery. This had the good psychological effect of identifying the coast gunners

With the field army instead of being out on a limb as they were in Singapore.

7 An expert in counter-battery work was sent down from India who organized a workable counter-battery organization. He also instructed the officers in that important aspect of artillery work.

8 The proportion of HE ammunition was augmented.

In conclusion it can be stated that the coast artillery did its job just by being there. Singapore was one of the most heavily defended ports anywhere and the existence of its enormously powerful artillery dictated the strategy of the war in those parts. The Japanese were fully aware of this and we knew that they knew, so the campaign started more or less exactly as it was expected it would. The Coast Artillery locked the front door and it was up to the field army to bolt the back door.

World History

World History