The General Staff of Army Group "C” had made several studies of a possible Allied landing of some strategic importance. For each hypothesis envisaged (Istria, Ravenna, Civitavecchia, Leghorn, Viareggio), the formations which would fight it had been detailed off, the routes they would have to take marked out, and their tasks laid down. Each hypothetical situation had been given a keyword. Kesselring only had to signal "Fa//

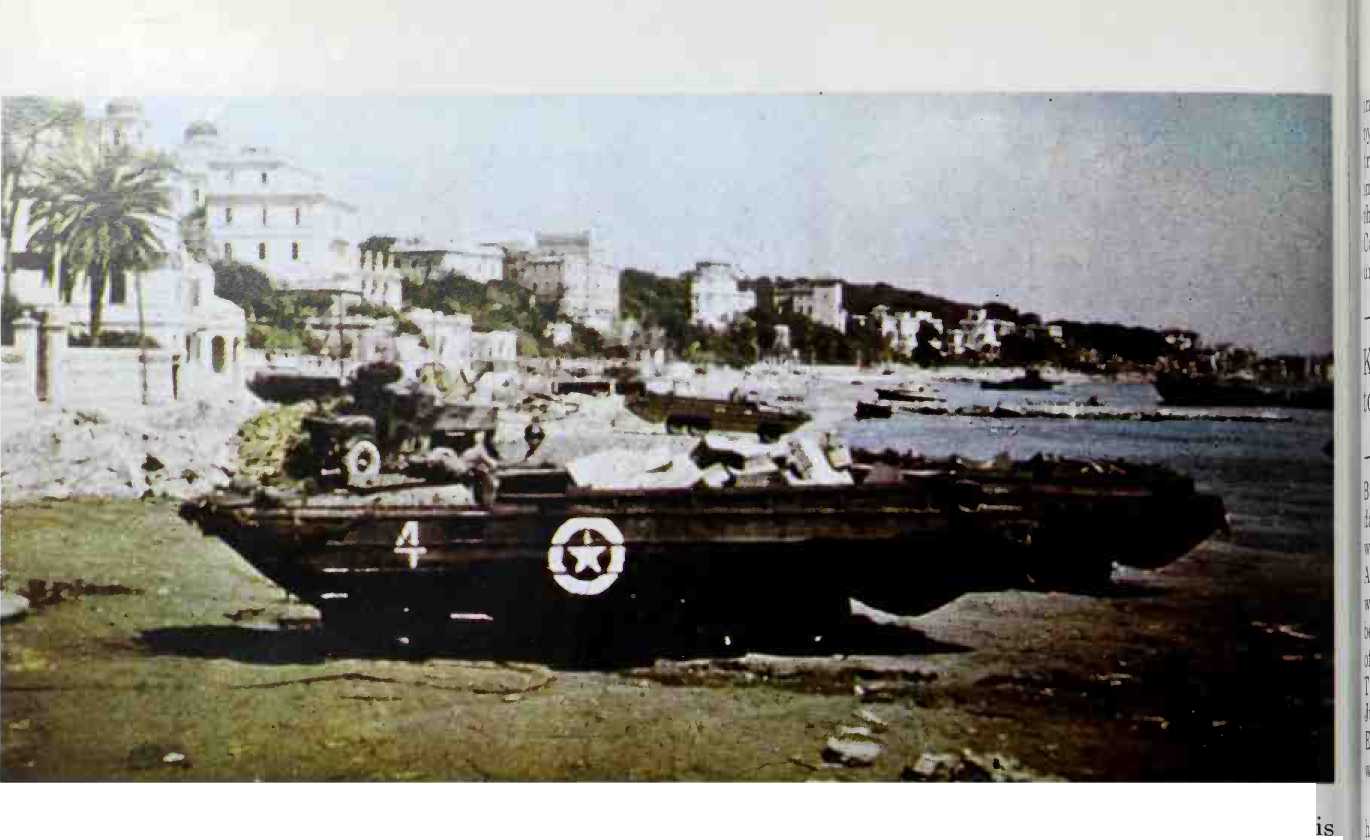

A Part of 5th Army’s complement (over-extravagant according to Churchill) of soft skinned and armoured vehicles.

V

Richard” for the following to converge on the Anzio bridgehead:

1. the "Hermann Goring” Panzer Division from the area of Frosinone and the 4th Parachute Division from Terni, both in I Parachute Corps (General Schlemm)

2. from the Sangro front LXXVl Panzer Corps (General Herr: 26th Panzer and 3rd Panzergrenadier Divisions); from the Garigliano front the 29th Panzer-grenadier Division, newly arrived in the sector: and

3. from northern Italy the staff of the 14th Army and the 65th and 362nd Divisions which had crossed the Apennines as quickly as the frost and snow would allow them.

But O. K.W. intervened and ordered Field-Marshal von Rundstedt to hand over to Kesselring the 715th Division, then stationed in the Marseilles area, and Colonel-General Lohr, commanding in the Balkans, to send him his 114th Jdger Division.

On January 23, when Colonel-General von Mackensen arrived to take charge of operations against the Allied forces, all that lay between Anzio and Rome was a detachment of the "Hermann Goring” Panzer Division and a hotchpotch of artillery ranging from the odd 8.8-cm A. A. to Italian, French, and Yugoslav field guns. Despite the talents of Kesselring as an improviser and the capabilities of his general staff, a week was to pass before the German 14th Army could offer any consistent opposition to the Allied offensive.

On the Allied side, however, Major-General John P. Lucas thought only of consolidating his bridgehead and getting ashore the balance of his corps, the 45th Division (Major-General W. Eagles) and the 1st Armoured Division (Major-General E. N. Harmon). It will be recognised that in so doing he was only carrying out the task allotted to the 5th Army. On January 28 his 1st Armoured Division had indeed captured Aprilia, over ten miles north of Anzio, but on his right the American 3rd Division had been driven back opposite Cisterna. On the same day Mackensen had three divisions in the line and enough units to make up a fourth; by the last day of the month he was to have eight.

Was a great strategic opportunity lost between dawn on January 22 and twilight on the 28th? In London Churchill was champing with impatience and wrote to Sir Harold Alexander: "I expected to see a wild cat roaring into the mountains-and what do I find? A whale wallowing on the beaches!”

Returning to the subject in his memoirs, Churchill wrote: "The spectacle of 18,000 vehicles accumulated ashore by the fourteenth day for only 70,000 men, or less than four men to a vehicle, including drivers and attendants. . . was astonishing.”

Churchill might perhaps be accused of yielding too easily to the spite he felt at the setbacks of Operation "Shingle”, for which he had pleaded so eagerly to Stalin and Roosevelt. These were, however, not the feelings of the official historian of the U. S. Navy who wrote ten years after the event:

"It was the only amphibious operation in that theater where the Army was unable promptly to exploit a successful landing, or where the enemy contained Allied forces on a beachhead for a prolonged period. Indeed, in the entire war there is none to compare with it; even the Okinawa campaign in the Pacific was shorter.”

We would go along with this statement, implying as it does that the blame lay here, were it not for General Truscott’s opinion, which is entirely opposed to Morison’s quoted above. Truscott lived through every detail of the Anzio landings as commander of the 3rd Division, then as second-in-command to General Lucas, whom he eventually replaced. He was recognised by his fellow-officers as a first-class leader, resolute, aggressive.

And very competent. His evidence therefore to be reckoned with;

"I suppose that armchair strategists will always labour under the delusion that there was a 'fleeting opportunity’ at Anzio during which some Napoleonic figure would have charged over the Colli Laziali (Alban Hills), played havoc with the German line of communications, and galloped on into Rome. Any such concept betrays lack of comprehension of the military problem involved. It was necessary to occupy the Corps Beachhead Line to prevent the enemy from interfering with the beaches, otherwise enemy artillery and armoured detachments operating against the flanks could have cut us off from the beach and prevented the unloading of troops, supplies, and equipment. As it was, the Corps Beachhead Line was barely distant enough to prevent direct artillery fire on the beaches.

"On January 24th (i. e. on D | 2) my division, with three Ranger battalions and the 504th Parachute Regiment attached, was extended on the Corps Beachhead Line, over a front of twenty miles... Two brigade groups of the British IstDivisionheld afrontofmore thanseven miles.”

In his opinion again the Allied high command overestimated the psychological effect on the enemy’s morale of the simple news of an Anglo-American land-

Ing behind the 10th Army. This is shown by the text of a leaflet dropped to German troops, pointing out the apparently impossible strategic situation in which they were now caught, pinned down at Cassino and outflanked at Anzio, and urging them to surrender.

World History

World History