Colonel Danny Matt, a tall, distinguished-looking man with a nicely trimmed beard and well-kept moustache, had received many wounds in battle over the years. In the Six Day War, he had commanded a paratroop brigade under Sharon in the Sinai, and twice landed by helicopter during the fighting in Syria towards the end of that war. During 1968, he had commanded the daring 120-mile raid into Egypt at Najh Hamadi. From 1969, he had held an appointment as commander of the reserve paratroop brigade that, under General Mordechai Gur, captured the Old City of Jerusalem during the fighting in the Six Day War. In later years, he was to rise to the rank of major-general, serving as President of the Military Courts and as Chief Co-ordinator of the territories administered by Israel in the West Bank and Gaza.

Early in the morning of the 15th, Matt received instructions to move his brigade, which was concentrated at the Mitla Pass, with orders to cross the Canal that night. The orders were that his brigade reconnaissance

Company and the company of engineers under his second-in-command would lead the crossing of the Canal and establish the first foothold on the west bank. The engineer company would cross at four points with demolition equipment. Everything had been prepared for the breakthrough. A special brigade second-in-command had been appointed to take charge of the ‘yard’. This was a brick-surfaced, hard stand at the western end of Tirtur Road and was located a few yards north of the point where the Canal joins the Great Bitter Lake, and just south-west of the Matzmed fortification. The area of the ‘yard’, measuring 700 yards by 150 yards, had been prepared by Sharon during his period as GOC Southern Command: protective sand walls surrounded it, and it marked the exact point for the crossing. There were positions in it for units to act as a fire base to engage enemy forces on the other side of the Canal, and the necessary arrangements for troop movement headquarters.

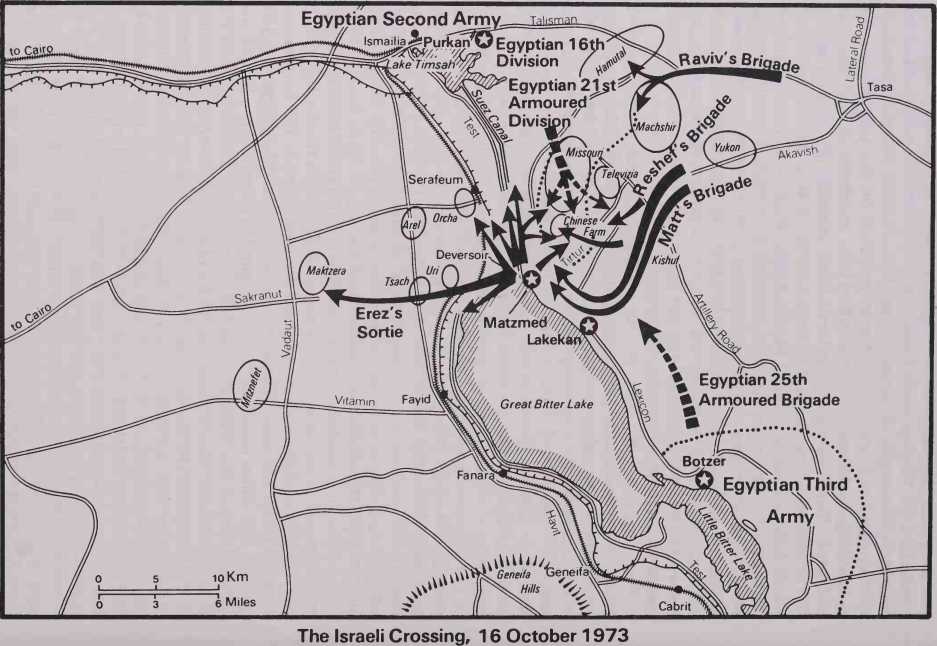

Following the initial foothold on the Egyptian side of the Canal, a battalion commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Dan would widen the bridgehead to the south, while a battalion under Lieutenant-Colonel Zvi would widen it northwards. This bridgehead was to be no less in width than three miles northwards, and the crossings of the sweet-water canal one to one-and-a-half miles westwards were to be seized. Matt was informed that he had 60 inflatable boats available and that they would be delivered to the brigade by 10.00 hours; by early afternoon, however, he had received none of the inflatable boats and only half of the 60 half-tracks that had been promised to him. The boats and half-tracks were only discovered by members of his staff in the mid-afternoon. Matt’s brigade moved out towards the rendezvous, but Israeli traffic control had apparently broken down completely — the roads were blocked for miles and there was an almost impassable traffic jam on the road leading to Tasa. Matt’s troops negotiated only three miles in some two hours. The traffic was limited to the roads because it was impossible to move off them into the sand dunes, in which all the wheeled vehicles remained stuck in the sand. Working its way forward under the most difficult conditions, part of Matt’s forces finally reached the embarkation area of the ‘yard’. He had only reached the inflatable boats that were supposed to have been delivered to him in the morning at 21.00 hours; because of the large number of soft vehicles in his brigade carrying the troops. Matt was obliged to adapt his programme accordingly, and he had to leave behind the brigade reconnaissance company, which was to have attacked the bridgehead on the west bank, together with the battalion of Lieutenant-Colonel Dan. It was discovered, too, that the hard stand at the ‘yard’ was incomplete at one of the two planned crossing points, so only the southern one was was to be used.

As Matt’s brigade advanced, led by a company of tanks, followed by the second-in-command of the brigade with the assault crossing force, the brigade forward headquarters and Dan’s battalion with the rest of the brigade following as best it could, the column came under artillery, missile and heavy machine-gun fire from the Akavish-Tirtur crossroads, some

1,000 yards distant. A force that Matt sent to establish itself on the crossroads to afford protection against any possible intervention from

North or east was completely destroyed. Thus, Matt continued this precarious move towards the Canal for the crossing with his very tenuous axis of advance and supply line under intense fire from the enemy. By 00.30 hours in the morning of the 16th, the assault group under the second-in-command of the brigade had entered the ‘yard’. Matt now ordered the entire artillery support at his disposal to open up on an area of the west bank some 1,000 yards wide by 220 yards deep.

Meanwhile, the half-tracks which had carried Matt’s forces to the ‘yard’ could not move as planned along the road running northwards and eastwards because the Egyptians had already occupied the road some 700 yards from Matt’s headquarters, and so the column of empty half-tracks moved back that night along the road on which the remaining loaded half-tracks were advancing. The situation was precarious in the extreme. However, despite the proximity of the Egyptians to the crossing point and the near pandemonium that reigned in the area, Sharon urged his division on.

At 01.35 hours on 16 October, the first wave of Israeli troops crossed the Canal and set foot on the west bank — ten days after the Egyptian onslaught on the east bank. The leading forces crossed the Canal as planned, with the Israeli artillery plastering the narrow landing strip with tons of shells. Brigade advanced headquarters crossed at 02.40 and, by

05.00 hours, all infantry forces had crossed; at 06.43, the first tank of Erez’s brigade crossed on a raft; by 08.00 hours, Matt’s forces held a bridgehead that extended three miles northwards from the Great Bitter Lake as had been planned. Resistance had been weak and, as his forces moved along the Egyptian ramp northwards, they came upon thirty Egyptians manning electronic equipment a mile to the north; part of the force was killed and part was taken prisoner. When isolated Egyptian armoured personnel carriers appeared, they were wiped out by the advancing Israeli forces. As they waited in position, the forces facing northwards observed a convoy of seven trucks loaded with 150 troops approaching unsuspectingly. They destroyed it and seized the four main crossings over the sweet-water canal. During the morning, leaving seven tanks to protect Matt’s forces, Erez took 21 tanks westward on his mission to seek out the surface-to-air missile sites.

However, the problem of the Chinese Farm hung as a black cloud over the Israeli Command, which was only too aware of the fact that, unless the lines of communication on the east bank were secured, the entire operation would be doomed. Aware of the pressure of the Egyptian 14th Armoured Brigade from ‘Missouri’ position on Reshefs brigade from the north, Bar-Lev gave advance warning to Adan’s division, being held in readiness to cross the first bridge, that it might have to intervene in the battle to open the roads to the Canal.

The situation at Southern Command Headquarters was indeed tense. Seeing what was happening on the east bank, and conscious of the bitter struggle that was going on in the corridor, the Minister of Defence, Moshe Dayan, proposed pulling back the paratroopers from the west bank: ‘We tried. It has been no go.’ He suggested giving up the idea of the crossing: ‘In the morning they will slaughter them on the other side.’ Gonen’s reaction was: ‘Had we known that this would happen in advance, we probably would not have initiated the crossing. But now that we are across we shall carry through to the bitter end. If there is no bridgehead today there will be one tomorrow, and if there is no bridgehead tomorrow there will be one in two days’ time.’ Bar-Lev overheard the conversation and, in his characteristically quiet voice, drawing out his words in an exaggeratedly slow manner, asked what they were talking about. When Gonen told him, he replied: ‘There is nothing at all to discuss.’

Once again, a major debate was developing between Sharon and Southern Command. Sharon was of the opinion that the success in establishing a bridgehead across the Canal must be exploited immediately, irrespective of whether or not a bridge was erected. In his view, Adan’s division should be transported on rafts to the other side and then the Israeli forces on the west bank should push on. Bar-Lev turned down this proposal on the 16th, and again on the 17th when Sharon renewed it, pointing out that this was not a raid across the Canal. He considered it would be the height of irresponsibility to launch an attack in corps strength numbering hundreds of tanks across the Canal, with a supply route that had not yet been secured and without a bridge. In his view, the tanks would run to a standstill within 24 hours; above all, he did not wish to rely on vulnerable rafts. He was of the opinion that Adan’s division must first complete the clearing of the corridor on the east bank of the Canal before moving over to the west bank.

The preconstructed bridge, which had broken down while being towed, was now being repaired, and the pontoon bridge had been moved forward, but all awaited the clearing of the roads to the Canal in order to move the bridges down. On the afternoon of the 16th, at the conference attended by Dayan, Bar-Lev and Gonen, the latter said that, if neither bridge nor pontoons reached the Canal, they would have to withdraw from the west bank. If there were pontoons but no bridge, the force would remain there, but Adan’s division could not be transferred to join it. As soon as a bridge was in position, all the forces could cross as planned.

Adan was already moving his forces forward in order to begin crossing on rafts when he was ordered to open Akavish and Tirtur. Southern Command had sent a paratroop force to deal with the Egyptian forces closing these roads, but they had moved along at night into action without adequate preparation and sustained very heavy casualties. Adan now ordered the paratroopers to leave Tirtur and concentrate on Akavish, but the fire was so heavy that the paratroopers could not disengage. While the paratroopers were fighting desperately between the two roads, Adan decided to make one more attempt. He sent a force of armoured personnel carriers along Akavish to report on the situation; the road was clear. Taking advantage of this situation, the pontoon bridging equipment was gradually moved towards the Canal. Protecting this move of the bridging equipment was a paratroop battalion, whose battalion commander realized that he must now hold the line facing the Egyptians at all costs. He created a line some 75-100 yards from the Egyptian lines with his paratroopers constantly risking their lives by rushing into no man’s land to evacuate the wounded. Despite the intense and murderous Egyptian fire, the paratroopers held on grimly in a battle that lasted for fourteen hours, facing a divisional position while, to the rear, movement towards the Canal continued.

Meanwhile, two armoured brigades moved to clear the area of Akavish and Tirtur under Adan’s command. Natke Nir’s brigade deployed to the south of Akavish, moving northwards across the road and continuing in the direction of Tirtur. Amir’s brigade pushed from east to west. Raviv’s brigade also joined in, and Adan pressed on the Egyptian forces in the Israeli corridor from east to west with three concentrated armoured brigades.

World History

World History