Some writers have given the impression that the Dreadnought was first a gleam in the eye exclusively of Sir John Fisher, Britain’s First Sea Lord. In fact, the special characteristics of this ship were the inevitable consequence of improvements in large-caliber gunnery. Before the Dreadnought was secretly launched in 1906, the U. S. Navy had under construction two ships with similar characteristics.

The development of smokeless powder and improved methods of fire control meant that naval battles would be fought at increasingly greater ranges, ultimately at ranges at which only the heaviest guns could reach the enemy. Then why not, it was argued, eliminate all but the largest caliber guns and add more of them? In 1901 Lieutenant Homer Poundstone did design such an “all-big-gun” ship for the U. S. Navy, but it was not then accepted. Battleships continued for some time to carry guns of as many as six diflFerent calibers, and no more than four apiece of the largest.

In 1905, however, Congress authorized construction of the Michigan and the South Carolina, each armed only with eight 12-inch guns in four two-gun turrets in pairs at the ends of the ship, and having one turret elevated so as to fire over the other. These ships were followed in the next two years by the Delaware and the North Dakota, each having main batteries of ten 12-inch guns and anti-torpedo-boat batteries of fourteen 5-inch guns. Long before any of the above-mentioned vessels were completed, the British revealed their Dreadnought, which also carried ten 12-inch guns and had a battery of 12-poimders to fight oflF torpedo-boat attacks. The

Dreadnought’s main battery firepower was two and a half times as great as that of any other battleship then afloat, but she could fire no heavier broadside than the Michigan or South Carolina because her turrets were all on deck level—three centerline, one on each beam. She carried 11 inches of armor on her belt and over her turrets, displaced 17,900 tons, and could make 21.5 knots.

Paralleling and stimulating the change in battleship design in the United States was a steady improvement in American gunnery. This was the achievement mainly of William S. Sims, who as a junior naval oflRcer had observed with dismay the wretched showing of the U. S. Navy’s gunners in comparison with those of European navies. Unable to get a hearing for his reform plans in

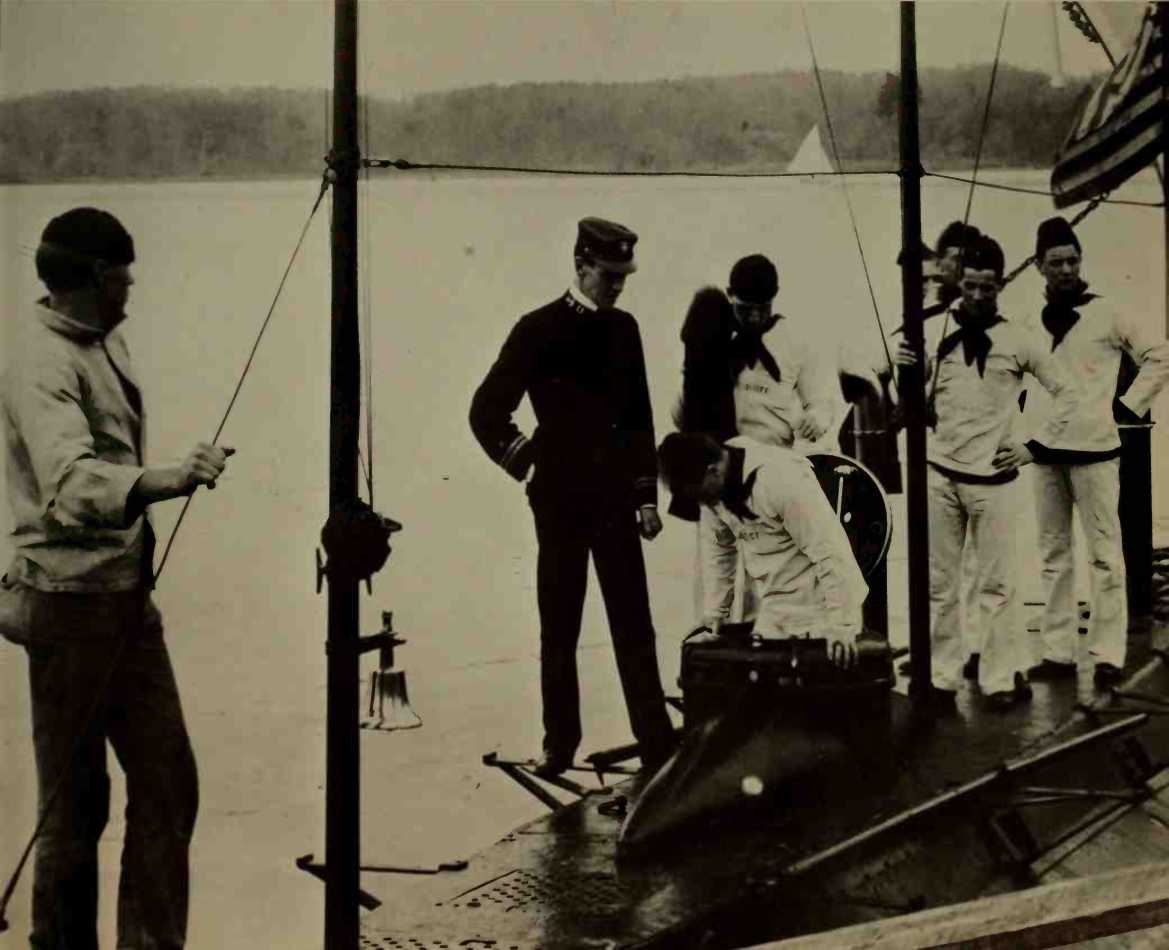

Midshipmen of the class of 1902 aboard the Navy’s first submarine, the Holland.

Commander Marc A. Mitscher in an early naval seaplane at Pensacola.

Ely lands aboard the Pennsylvania.

The Navy Department, he had appealed directly to President Roosevelt, who gave them a favorable endorsement. Rear Admiral Henry C. Taylor, the progressive new chief of the Bureau of Navigation, appointed Sims inspector of target practice, a post which he held from 1902 to 1909. The U. S. Navy, using methods that Sims borrowed from the British navy, achieved a true revolution in gunnery, and at length rivaled the best navies in the world.

The 1898 Naval Appropriations Act provided for 16 destroyers, the first in the U. S. Navy. Two years later the Navy commissioned its first submarine, the 54-foot-long Holland. For several years the Holland was based during the winter at the Naval Academy, where it was used to train midshipmen, including Chester W. Nimitz.

NAVAL AVIATION

The U. S. Navy early took an interest in the newly invented airplane, seeing its possibilities for reconnaissance and the spotting of gunfire. At Norfolk in 1910 a civilian flyer, Eugene Ely, demonstrated the possibility of teaming planes and ships by flying a plane off a specially constructed launching deck on the cruiser Birmingham. Two months later he took off from shore at San Francisco, landed on an improvised flight deck on the cruiser Pennsylvania, and was brought to a halt by hooks under his aircraft that caught on to lines stretched athwartships between sandbags. He thus proved the practicability of the aircraft carrier.

In 1911 the Navy, on the strength of a $25,000 Congressional appropriation, contracted for two land planes, a Curtiss and a Wright, and one of Glenn Curtiss' newly developed amphibians. Four officers were then sent to the Curtiss and the Wright brothers factories to learn how to fly them. The next spring these officers. Lieutenants Theodore Ellyson, John Rodgers, and John Towers, and Ensign Victor Herbster, along with some beginners, set up a primitive aviation camp at Annapolis. Ellyson flew a plane shot from a compressed-air catapult mounted on a barge; and Towers gave Lieutenant Ernest J. King, then the executive officer of the Annapolis Engineering Experiment Station, his first airplane ride, a 20-minute flight at 60 miles an hour. Both Towers and King were later carrier commanders and chiefs of the Bureau of Aeronautics. In 1913 the aviation camp was transferred to Florida, where it became the nucleus of the Pensacola Naval Air Station, the Navy’s “academy of the air.”

For lack of adequate appropriations, little more was achieved in naval aviation during the next few years. When the United States entered World War I, the Navy had only 39 qualified aviators and some 50 planes.

World History

World History