The little Italian port of Anzio was the scene, in early 1944, of one of the great ‘might have been' battles of the Second World War. Like Arnhem which might have ended the war in the west in September 1944, or Army Group Center’s offensive in August 1941 which might have defeated Russia in the first four months of Operation Barbarossa, Anzio might have broken the costly stalemate of the Italian front before midsummer of Invasion year, captured Rome, 33 miles to the north, and driven the Germans deep into northern Italy.

This single stroke would have released vitally needed shipping for the D-day operation, brought the Allied bombers closer to their targets in southern Germany and outflanked German positions in the Balkans, one of her major sources of oil and mineral supplies. It would have also dealt a considerable blow to Hitler’s prestige and almost certainly cost him a major part of the very large force he maintained in southern Italy to keep the Allied Mediterranean Expeditionary Force at bay. Anzio, in fact, achieved none of these things. Why was the operation, so rich in promise, so empty of fulfillment?

In the early winter of 1943, the Allied armies, landed near Naples in September, were brought to a frustrating halt in the mountains south of Rome. They had run into exceptionally difficult terrain and an unexpectedly severe winter of rain and snow. The Germans

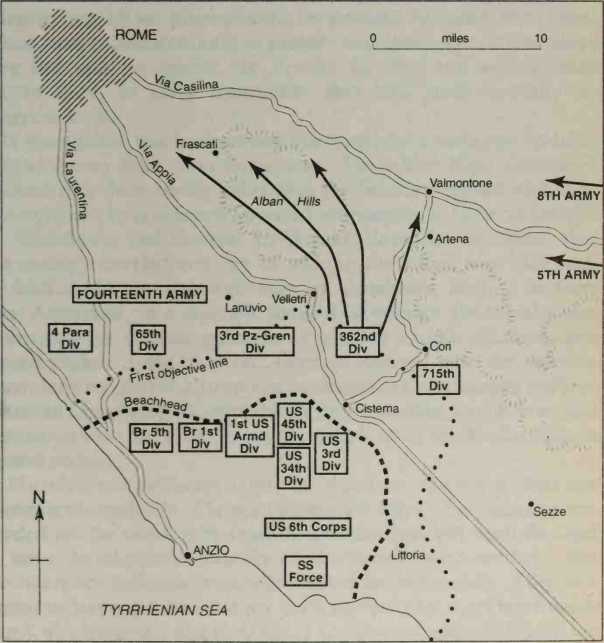

5.9 The Battle for Anzio, May 1944

Also presented problems - there were more of them than the Allied High Command had anticipated and they had built a belt of fortifications, the Gustav Line, which, with the advantages of climate and geography, gave a coherency to their defensive line.

The only progress made by the Allies’ two armies, the American Fifth on the Mediterranean coast and the British Eighth on the Adriatic, was by set-piece assaults on strongly defended river lines. These were time-consuming to prepare and cosdy to execute. Since they had run up against the heavily fortified and well-manned Gustav Line, in early November, they had made virtually no progress at all.

It was against this background that plans for a seaborne invasion behind enemy lines were formulated. The Allied High Command realized that their earlier belief that the Germans would withdraw into northern Italy if heavily pressed was mistaken. General Dwight D. Eisenhower and General Sir Harold Alexander concluded that the enemy’s current strategy of making the Allies win Italy inch by inch could be countered only by a seaborne landing in their rear. Alexander, in a directive dated 8 November 1943, laid down a timetable for such an operation; it entailed a triple offensive, first by the Eighth Army to attract German reserves onto the Adriatic coast, then by the Fifth to set the campaign again in motion towards Rome and finally by an amphibious force, landing near Rome, and linking up with the Fifth across the river lines of the Mediterranean coastal plain.

The plan was orthodox - but the means to execute it were not immediately available. The plan demanded ships - but shipping was needed for the coming Normandy invasion and had been directed to leave the Mediterranean forthwith. Troops were needed - but the necessary divisions were also wanted for Normandy. They had begun to leave and had not yet been replaced by the Free French Army which was training in Africa. The plan, code-named Operation Shingle, was, after a feasibility study, therefore shelved. But it was not forgotten. As the winter fighting increased in severity, and apparent futility, the idea of a seaborne descent near Rome came to appear more and more attractive to the protagonists of the original plan, notably Alexander and the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill.

On 22 December, Shingle was officially canceled; but on the following day Churchill insisted that it be reconsidered. As the

Author of the heart-breaking Gallipoli failure of the First World War, Churchill’s credentials to oversee a revived Shingle did not bear close examination. But he could well argue, if anyone had drawn the parallel, that the Allied position in the Mediterranean was far more favorable in 1944 than in 1915, and that while the objectives Shingle proposed were more limited than those intended at Gallipoli, the investment required was proportionately more limited.

He could and did argue that Shingle made excellent military sense - if only by contrast with the fighting along the narrow mountain roads and hidden defiles to which their current strategy condemned the Allies. There they were unable to disguise either the timing or the direction of their strokes and could gain little advantage from their air superiority. A seaborne movement offered the chance to surprise the enemy both in space and time, and to force him into battle on the naked plain, while supplying themselves plentifully along the broad highway of the Mediterranean. If the enterprise were successful, moreover, it would give them Rome, put the Balkans under threat and perhaps - and here the argument became speculation - even make Operation Overlord, the invasion of Normandy, unnecessary.

It was vital, if Shingle was to work at all, to delay the transfer out of the Mediterranean of the necessary shipping. By direct intervention with President Roosevelt, Churchill secured the retention, first until 15 January, then until 5 February, of 68 Landing Ship Tanks (LSTs), the basic requirement of a seaborne landing. As planning proceeded, Churchill made further requests for logistic supplies and secured them. At the same time he ensured that there was no wavering in the enthusiasm of Gen. Alexander, Army Group Commander, and of Lieutenant General Mark Clark, the American Fifth Army Commander, two of the three men who had chosen Anzio for the invasion point.

In fact, this was unlikely for both had strong, if different, personal motives for wishing the operation well. Alexander, disappointed that Eisenhower, rather than himself, had been appointed Supreme Commander, was resolved that the struggle for Italy should not become a stalemated sideshow - and, without Shingle, it threatened to become just that.

Gen. Clark, who felt that his Fifth Army had not been given the credit its achievements deserved, ached for the glory of capturing Rome. His American and British divisions, now pinned to the river

Valley floors by fire from the heights of the Monte Cassino range, were 100 miles short of the capital. He counted on Shingle to release them from the stalemate of the plains below Monte Cassino. Seventy miles separate Anzio from Cassino, and Clark thought that, given determination, the launching of concentrated offensives from the two spots should break the German defense on the west coast and lead him into Rome.

This was Churchill’s hope and, having secured the necessary equipment for his commanders, he left them to put the plan into action. But the translation of mihtary decisions into effect always reveals unanticipated difficulties. The preparation of Shingle was no exception. Further staff study suggested that the Germans would probably react strongly to the initial landing, and that a two-division landing, for which Churchill had had to commit his personal prestige to find the shipping, might not survive the onslaught. Further shipping, and more men, had to be found to land with three divisions.

The final order of battle, therefore, included, besides the British 1st and American 3rd Divisions, the American 45th Infantry and 1st Armored Divisions, as well as members of American Parachute and Ranger and British Commando battalions. The whole was to be subordinate to a Corps headquarters -¦ the US 6th Corps. This was debatably too small to handle the operations of a force though it had grown from the initial planning figure of 24,000 to a final 110,000. Doubts also emerged about the efficiency of the force itself. At a dress-rehearsal in Naples Bay, both the 1st and 3rd Divisions mishandled their equipment, losing 40 DUKWs (the amphibious lorry on which cross-beach mobility depended) and two batteries of 105 mm howitzers; while the naval parties operating the landing craft made a series of unnerving mistakes. It was not a happy augury.

These events badly worried the already anxious commander of 6th Corps, Major General John R. Lucas. An experienced and respected soldier, Lucas was not happy with the Anzio idea and expressed his doubts strongly and continuously in the pages of his diary. He described himself as unusually tender-hearted for a general in an army which traditionally took a blood-and-guts attitude to the prospect of casualties and he feared he was leading, or worse, sending, his men to their deaths.

Hence his growing obsession, which the weeks of preparation made more and more apparent, with reinforcement and re-supply

Considerations. It was vital, in his view, that the men in the beachhead should have ashore with them the largest possible quantity of armored vehicles and artillery pieces as well as ammunition and petrol. Given these, and air support, the beach-head troops would be able to repel a counter-attack, which Lucas expected to come swiftly and in strength, despite the different story from Allied Intelligence.

His superior, Mark Clark, an abler man than his posturing suggested, was sensitive to Lucas’s anxieties, which to some extent he shared. Consequently, he refrained from giving Lucas the additional responsibility for a decisive breakout from the bridgehead. The orders Clark issued to 6th Corps were for ‘an advance on’ the Alban Hills - the feature which commands the land between Anzio and Rome - not for an advance ‘onto’. This ambiguity gave Lucas the option of halting his troops short of the objective if he felt that the strength of enemy reaction threatened his beach-head.

The Germans were also making their plans. The Luftwaffe Field Marshal Albert Kesselring had been preferred to Field Marshal Erwin Rommel for the post of Commander-in-Chief in Italy because of his optimistic and generally correct forecasts of the way events would go in the peninsula. Kesselring was aware that, over a distance of several hundred miles, both his flanks were vulnerable to amphibious assault. He suspected, however, that the coast near Rome was the most likely spot for the Allies to choose, and he accordingly kept two divisions in reserve nearby. They were divisions he could hardly spare, for his armies were at full stretch on the Gustav Line, the cross-peninsula German defense line from which. Hitler had ordered, there was to be no retreat. He was aware, moreover, that even this reserve might not be sufficient to contain a landing, for the Allies might outnumber it before reinforcements, which could only come from southern France, the Balkans and the far north of Italy, had arrived.

On 18 January, and only after receiving the firmest assurances of the unlikelihood of an Allied landing in the near future, from his own and higher Intelligence sources, he agreed to send his two reserve divisions from Rome to Cassino, where Clark’s Fifth Army had just succeeded in forcing the line of the Garigliano. General Heinrich von Vietinghoff, commanding the Tenth Army, had represented this breach of his sector of the Gustav Line as potentially catastrophic, for it threatened to outflank the Monte Cassino position on which

The whole line hinged. Kesselring was persuaded by his entreaties. What neither appreciated was that Clark, though delighted by this local success, had planned it precisely as a means of clearing the Anzio area of anti-invasion forces. Once Lucas was ashore Clark then intended to launch a major offensive from the Garigliano bridgehead, directed towards Anzio, the Alban Hills - and Rome. The Germans in between, if the strategy proved right, would flee, or surrender to the pincer attack.

Thus Lucas, thanks to an excellent stroke of strategic deception by his own commander, and to the enemy’s faulty Intelligence, was to enjoy the most precious advantage an amphibious force leader can obtain - total surprise. His fleet of 240 landing craft and 120 warships made an undetected overnight passage northwards from Naples. In the early morning of 22 January 1944, they began to unload the two assault divisions - 1st British, 3rd US - on beaches left and right of Anzio without interruption from the enemy, apart from some light, uncoordinated cannonading by a few, soon-silenced, batteries. By midnight nine-tenths of the assault force (36,000 men and 3,000 vehicles) had come ashore for a loss of 13 dead, and had established a perimeter between two and three miles inland. The Allied air forces had flown 1,200 sorties, but had not been opposed. The port had been captured intact and was now ready to receive supplies from the fleet which swung untroubled at anchor offshore.

Lucas felt, and rightly felt, that he had done well. Indeed as landings go, the first day at Anzio must be regarded as an impeccable exercise in that particular tactical form. But success did not dispel Lucas’s anxieties, for he now feared a major enemy counter-blow. Rather than cripple the expected counter-attack by seizing commanding terrain features and communication centers inland, he redoubled his concentration on building up his base and perimeter defenses. For the next few days the American 3rd Division pushed cautiously inland, the British 1st Division, on its left, rather more boldly. But both failed to reach their obvious objectives, Campoleone and Cisterna, from which an advance on the Alban Hills must start; and neither was urged onward with any fervency by Lucas. He was now directly under the eye of Clark, who had come to see the bridgehead for himself. But even the presence of his superior could not stir him to action, though his diary reveals that it rattled him. When he was ready, he wrote, he would move. He thought he would be ready by 30 January.

Unfortunately for the Allies, the Germans were ready also. If there was one thing at which their staffs had always excelled, it was the rapid improvisation of defense and counter-attack, and this war had given them all the practice they needed at perfecting their procedures. The landing had badly frightened them - Vietinghoff was so alarmed that he had begged Kesselring for permission to withdraw from the commanding Cassino position. But Oberbefehlshaber (CinC) Kesselring was not prepared to fall for Clark’s ploy and had kept his nerve. He called up his Alarmeinheiten and settled down to win the build-up. Alarmeinheiten were ‘paper’ units, formed from clerks, drivers and men returning from leave and all German headquarters had plans to form such units in an emergency. German headquarters in Rome sent several of these units to the beach-head in the first day.

Meanwhile Kesselring called for better units to replace them. From the north of Rome came the 4th Parachute and Hermann Goering Panzer Divisions, from southern France the 715th Division, from the Balkans the 114th, from northern Italy the 92nd, 65th and 362nd Divisions and the 16th SS Panzer Grenadier Division. From the Gustav Line, which Kesselring insisted should be thinned out, came the 3rd Panzer, the 1st Parachute and the 71st Divisions. Not all of these were destined for Anzio. Kesselring had two crises on his hands, the Anzio beach-head and Cassino, and needed a surplus of units with which to juggle his way to stability. By 30 January, he had extracted sufficient force from these newly liberated reserves to have sealed off the Allied bridgehead and to be contemplating his own counter-offensive, which he had scheduled for 2 February.

Lucas’s methodical preparation of his offensive had thus ensured the conditions which would bring about its failure. For his postponement of the capture of Cistema and Campoleone had not only allowed the Germans to build up opposition on the commanding ground of the region; it had also betrayed to them what would be the thrust of his eventual attack. If he had taken these two places, his forces could have moved north-west, north or north-east. Cramped within his original bridgehead, with the coast on his left and the impassable inundations of the Pontine Marshes on his right, he could only attack straight ahead, due north. There the Germans sat and waited for him.

Lucas planned his H-hour, the attack time, for 0200 on 30 January. This timing gave his infantrymen some advantage for

Darkness covered the movements of the Ranger force he sent along the dry bottom of the Pantano ditch towards Cisterna. But it also concealed the Germans assembling stealthily to ambush them. Of the 767 Rangers who set out on this commando penetration only six returned to the Allied lines. Their comrades of the 1st and 3rd Armored Divisions, following up in a conventional assault, suffered fewer casualties but nevertheless met desperate resistance and, after an advance of three miles in three days, which brought them near to the vital Highway 7, were forced to a halt. Only in the British sector was there promising progress. Here the veteran 1st Division had launched its attack from the positions it had won a week before near Aprilia. (These were The Factory’, as the Allies termed the Fascist model farm at Aprilia, and The Flyover’, a road bridge which carried a minor road over the Anzio-Campoleone road.) But it was made at a dreadful price.

The countryside beyond the roads was a maze of gullies or ‘wadis’, and these denied protection to the flanks of 3rd Brigade, attacking up the Anzio-Campoleone highway. Its three battalions suffered crippling casualties as a result; one, the 2nd Sherwood Foresters, was almost completely destroyed in the final assault on Campoleone. ‘There were dead bodies everywhere,’ wrote an American visitor to the scene, ‘I have never seen so many dead men in one place. They lay so close I had to step with care.’

Though the offensive of 30 January to 3 February was a failure, in that it cost much for little, fell short of a break-out and further depressed Lucas at a time when buoyant leadership was becoming vital to the beleaguered invaders, it did achieve some positive gains for the Allies. It had inflicted heavy losses on the Germans, who had no way of suppressing the fire of the Allied fleet or of chasing off the Allied air force, and had no real answer to the enormous weight of artillery the Allies could always deliver. Both the British 1st and American 3rd Divisions had penetrated Kesselring’s main line of resistance; and the upset they had inflicted forced him to postpone the planned 2 February offensive.

The Allied assault had averted a German offensive designed to obliterate the Anzio beach-head and sweep the Allies into the sea. But if it had avoided another Dunkirk, Colonel General Eberhard von Mackensen, whose Fourteenth Army Headquarters Kesselring had brought down to oversee German operations at Anzio, was determined not to let the Allies consolidate. He inaugurated the

First of a series of minor attacks, beginning on 3 February, and chiefly aimed at the British Campoleone salient. All of these were designed to win the ground necessary for a major counterblow. He was unable to shift the British on 3 February but kept them subjected to fierce pressure which, the next day, drove them out of most of their salient. On 7 February, Mackensen attacked towards The Factory* and nearly took it. On 9 February he got possession of Aprilia village but failed to take The Factory*. It fell next day, was retaken by the British in a counter-attack, and only passed finally from their hands on 11 February.

The British 1st Division had now lost half its strength, which, as always in a stricken infantry formation, meant much more than half its infantrymen. A fresh British division, the 56th, had landed but it was needed elsewhere in the line and could not relieve the 1st and much of its front was, on Lucas*s orders, taken over by the American 45th Division with the aim of fighting the Germans out of Aprilia. Lucas seemed to have litde fight left in him. Badgered by his sup>eri-ors, Mark Clark and Alexander, who were frequent visitors to the beach-head; menaced by the appointment of a deputy commander, Major General Lucian K. Truscott, whom he suspocted of being kept ready to supplant him, and more distressed than ever by the losses his men were suffering, Lucas busied himself in supervising the preparation of a ‘final beach-head line* of strongpoints, roughly following the perimeter of 24 January.

In the coming days the men at the front, who were also frantically strengthening their tactical positions, were to feel grateful for the sense of refuge the final beach-head line offered, for on 16 February Mackensen unleashed his long-prepared offensive. There were two thrusts to the assault. The first, against the British 56th Division on the west bridge-head, was by 4th Parachute and 65th Divisions. The other, and main attack, by 3rd Panzer Grenadier, 114th and 715th Divisions, with 29th Panzer Grenadier and 26th Panzer Divisions in support, was down the now dreadfully familiar axis of the Campoleone-Anzio road. It was spoarheaded by a unit chosen specially for the task by Hitler - the Infanterie Lehr Regiment. Successor to the Lehr Regiment of the Kaiser*s Guard, and brother to the mighty Panzer Lehr Division, the regiment looked, and thought itself, invincible. In fact, the only activity it was accustomed to were military displays and demonstrations in Germany. It was inexporienced and overconfident. Exposed to the defiant resistance

Of the American 45th Division, astride the main road, the Nazi regiment suffered heavy casualties and its discipline broke.

Equally disappointing - for those like Hitler, who believed in fancy solutions to old-fashioned military problems - was the performance of the ‘Goliath’, a remote-control miniature tank. Each of the 13 such tanks used in the attack carried 200 lb of explosive at 6 m. p.h. for a maximum distance of 2,000 ft. It was supposed to open a cheap way into an enemy position. All bogged down on the approach; Allied fire destroyed three, the rest were dragged ignominiously back to base.

But these two reverses were compensated by substantial German successes on 16 February. Although unable to deploy their tanks off the road, just as the Allies had been unable to do during their offensive, Mackensen’s divisions had inflicted substantial loss on the British 56th and American 45th Divisions and driven both back. Behind one of their rare air bombardments they continued their attacks during the night, and attacked again early next morning down the main road. A further air raid in mid-morning aided their advance, and by noon they had secured a salient two miles deep and one mile wide in the 45th’s front. They were now only a mile from Lucas’s ‘final beach-head line’. But the Germans could get no farther. Lucas found reinforcements, which included the battered British 1st Division, and with the help of these troops the 45th held out.

The Germans, by the end of the day, had suffered such heavy losses in their engaged infantry battalions, which were down to a rifle strength of 150 to 200 men, that Mackensen persuaded Kesselring that he could only continue if allowed to commit his panzer reserve -26th and 29th Divisions. Kesselring, though not optimistic, agreed. They attacked next day, 18 February, and managed to enlarge the breach considerably. Then they ran into a carefully prepared fire-trap laid on by a ‘grand battery’ of 200 Allied guns. Five times the Germans tried to break through the barrage that the battery laid around the Flyover on the Anzio road but each time their formations were broken up and driven back. Still they rallied to attack again in the afternoon and only the committal of final Allied reserves from Anzio, and more self-sacrifice by the 45th and 56th Divisions, turned back the assault.

The Germans had very nearly broken through on the afternoon of 18 February and Mackenson continued to attack, at a lower intensity, for the rest of the month. But after 18 February both he and Kesselring accepted that their offensive must end. With the

Cessation of the great Allied attack on Cassino on 13 February, the reason for the German offensive had gone. They had also, with 5,000 casualties in five days, run out of troops and supplies were low.

The Allies too had suffered heavy losses in men. But their supply line, though occasionally interrupted by the new German radio-controlled glider bomb - most sj>ectacularly when the ammunition-ship Elihu Yale was blown up - was never broken and continued to provide ammunition in a quantity the enemy could not hope to match. Profusion of ammunition, after stark bravery, was the principal reason for the Allies’ survival in the beach-head. After 20 February the German commanders tacitly accepted that the continued existence of the beach-head was a situation they would have to five with.

For the Allies, however, mere survival fell rather short of a victory. It was enough to satisfy Lucas, but not his superiors who, in the aftermath of the German winter-offensive, promoted him out of his command and into obscurity. With his departure, and the Germans’ exhaustion, the beach-head relapsed into a lethal slumber. Maj. Gen. Truscott, who could have won the ground Lucas dared not grasp for, was ironically compelled to oversee a prolonged period of siege-warfare ~ something for which his predecessor was perfectly fitted.

Yet perhaps it was still not Lucas’s sort of battle. For despite the lack of movement on either side, Anzio remained a place of death, the death of young soldiers whom Lucas had cherished more deeply with each day of battle. And the deaths they were to suffer, in this gentle Italian landscape, warming to the spring, were those of a different war in another country - the deaths of soldiers of the First World War in the trenches of Flanders. For at Anzio, as at Ypres, the lines ran within grenade-throwing distance of each other, and men spent their days, throughout the ‘lull’ of March, April and May, pressed against the earth walls of their bunkers, listening for the distinctive discharge noises of short-range weapons and bracing themselves to withstand the shock of the explosion. Rest, when it came, took tired units no more than three or four miles from the line where shelling, which at least they were spared ‘up front’ by their proximity to the enemy, was a constant harassment and killer.

There was also the German propaganda barrage. Its message meant nothing to many soldiers; to others it was demoralizing and provocative. Radio broadcasts from Rome warned of the danger

And horror of further fighting and encouraged desertion. Leaflets fired over in shells alleged unfaithfulness on the part of wives and girlfriends at home - leaflets for the British troops spoke of English girls enjoying themselves with the Americans encamped in ‘Merry Old England’ while, for the American soldiers, the villain was the archetypal Jew. One of the most effective leaflets carried the chilling legend, ‘The Beachhead has become a Death’s Head’ and showed a map of Anzio over which a skull was superimposed.

All who survived the ‘lull’ at Anzio testify to the tension, caused by constant alarms and persistent sense of claustrophobia, they experienced within the perimeter. When orders came, on 23 May, to break out and meet the spearhead probing north from Monte Cassino, they were greeted with the sort of genuine enthusiasm soldiers rarely accord the prospect of risk. The Allies had been too long at Anzio. It had proved no short-cut from the path to Rome.

Ought Anzio to have worked? Mark Clark thought so; Alexander thought so; Churchill continued to think so, long after the war’s western focus of effort had moved out of the Mediterranean. Were they all wrong? It depends whether one wants a tactical or strategic answer to the question. Tactically, there seems little doubt that Lucas might have seized the high ground between the beach-head and Rome - the Alban Hills - had he pressed on hard from his perimeter in the first three or four days after the landing. But equally there seems little doubt that to have pressed on farther, to Rome itself, would, even though the city lay temporarily undefended, have resulted in the destruction of his Corps.

Hitler’s snap judgement about Anzio was that it betrayed an Allied reluctance to risk a cross-channel invasion and he was willing in consequence to release reserves from much farther afield than usual to crush the landing. Given this reaction, Lucas’s caution looks justified. But, his critics argue, bolder action would have frightened the Germans into thinning out the Cassino front which, in turn, would have heightened the chance of the Allies breaking the Gustav Line and dashing to his rescue.

That argument shifts the debate from the tactical to the strategic level. Its validity is dubious also - Cassino and Anzio are so far apart (about 70 miles) that the two Allied forces, given their strength relative to each other and to the enemy’s, could not mutually assist each other. A much stronger punch at Cassino, a much bigger landing at Anzio, a weaker Tenth Army, a slower, smaller reinforcement by

Hitler - any of these would have turned the trick for Mark Clark, Alexander, Churchill, perhaps even for the depressive Lucas. But these alterations in the strategic equation presuppose a major revision of priorities in the Allied plans for the conduct of the war in 1944. Not only was there no such revision but American opinion, at the highest level, was rockfast against it.

Roosevelt and Marshall were determined to transfer the focus of Allied war-making out of the Mediterranean and into Normandy, agreed to Anzio with bad grace and resolved to concede it with no more than would pacify Churchill. Given their attitude, the 70 miles between Cassino and Anzio were unbridgeable by any Allied effort. Hitler’s hopes and fears - fears that he might be about to lose both the Balkans and Italy; hopes that a brutal extinction of the Anzio beach-head might deter the Allies from risking a landing elsewhere - determined that the Germans would give Lucas and Mark Clark no help either. It was this combination of enemy determination and Allied lack of enthusiasm which robbed the Anzio operation of its chance of success and made the subsequent battle so terrible.

World History

World History