Late in 1942, at the time North Africa was being cleared of Axis troops, the Allies decided the first step in the retaking of Europe should be Sicily, a region of Italy separated from the mainland by a narrow strait at its southeastern tip. Someone once said that Sicily looks like a football about ready to be kicked by the Itahan boot.

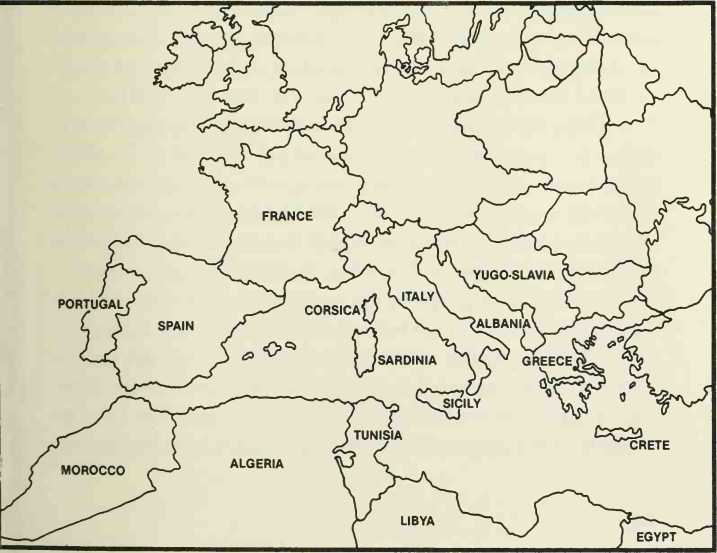

A quick glance at a map of the Mediterranean Sea shows Sicily to be the logical stepping-stone from the North African coast into southern Europe. The northern tip of Tunisia is, in fact, only 95 miles from the Sicilian coast. Because it was such an inviting target, the Alhes knew that the Germans and Italians would be expecting the attack and preparing for it.

How, the Alhes asked themselves, could they get the enemy to believe the landings were to be made elsewhere?

Lieut. Comdr. Ewen Montagu and his colleagues

At British Naval Intelligence believed they had the answer: Take an anonymous corpse, give him an identity as a British officer, plant phony documents on him indicating a planned Allied landing on Greece and Sardinia, and allow his body to wash ashore on the Spanish coast. Wait for the body to be discovered by the Spanish and the documents to be turned over to the Germans. Then hope that the Germans would believe the documents were genuine and would change their Mediterranean defense plans so the Allies could invade Sicily with minimum losses.

To confuse and mislead the enemy has always been one of the chief goals of warring nations. Virtually every campaign, indeed, every battle, offers evi-

SICILY, OFF ITALY’S SOUTHWESTERN TIP, WAS LOGICAL STEPPING-STONE INTO SOUTHERN EUROPE. (Neil Katine, Herb Field Art Studio)

Dence of one side’s attempt to deceive the other.

The plan involving the anonymous corpse was one of the most preposterous hoaxes of its type hatched during World War II. Yet it was more successful than anyone ever dreamed it would be.

When Comdr. Montagu revealed his scheme for the first time, it immediately raised several questions, such as, where could a body be obtained? That was the most difficult question of all.

Nobody involved in the hoax liked the idea of tinkering with the sanctity of a human body. But the realization that the project could result in the saving of many lives helped overcome their misgivings.

Comdr. Montagu learned of a man in his midthirties who had just died of pneumonia. He sought out the man’s relatives and explained as much as he could without giving the secret away. It was a worthwhile cause, he told the relatives, and the man would eventually receive a proper burial. His name would never be revealed. The relatives granted Naval Intelligence permission to use the body.

The corpse was given the name of Wilham Martin and the rank of major in the Royal Marines. An identification card was prepared and the appropriate stamps put on it. Comdr. Montagu didn’t want the card to look brand-new so he spent hours rubbing it up and down his trouser leg to age it.

British intelligence experts not only created an identity for the body, but they also made up a personality for it. Letters that the major carried in his pocket gave some idea of what kind of person he was.

A girl friend named Pam was invented for the major. Two letters were handwritten and signed by

Her. In one, she enclosed a snapshot. The photograph actually depicted a friend of Comdr. Montagu’s.

The correspondence that Major Martin carried disclosed that he and Pam were planning to be married and that he had given her an engagement ring. A bill from a jewelry store for the ring was included among the major’s papers. A bill from a Naval and Military Club, where he supposedly stayed the night before his ill-fated airplane flight, was also included.

Comdr. Montagu and his fellow conspirators filled Major Martin’s pockets with the usual odds and ends a man carries, including several coins, a ring of keys, a pencil stub, a packet of cigarettes, a box of matches, and two theater ticket stubs. A wristwatch was placed on one wrist. A chain with a silver cross and an identification tag was placed around his neck. A wallet was placed in his right back pocket. It contained the photograph of Pam, a book of stamps with two missing, an invitation to the Cabaret Club in London, the identification card, and several pound notes.

Other parts of the plan began to fall into place. It was decided that papers being carried by Major Martin would make it appear that he had floated ashore from an aircraft that had crash-landed at sea.

How should the body fall into enemy hands? Where should it float ashore? Germany itself was ruled out. Comdr. Montagu did not want German doctors examining the body firsthand. Eventually Huelva, Spain, not far from the Portuguese border, was chosen as the landing point for the body. Intelligence officials knew that there was a top-notch German secret agent at Huelva. He would be certain to

Learn of the body and the documents it carried.

The problem of getting Major Martin into the waters off the Spanish coast had to be solved. The body could not be dropped from an airplane. That would cause injury to it. A ship would be hkely to attract attention ashore. Comdr. Montagu and his associates decided that a submarine was the best bet. It could get close to the shoreline without being seen. British naval officials gave the assignment to the submarine Seraph.

Major Martin was to be carrying a briefcase that contained several documents. It was to be attached to his body with a leather-covered chain, the type used by some bank messengers when carrying valuable securities. The chain prevented the briefcase from being snatched away from them.

In the case of Major Martin, it was hoped that the Spanish and Germans would believe that the chain served the same purpose. It was actually intended to prevent the briefcase from becoming separated from him.

A great amount of planning went into the preparation of the essential document that Major Martin was to carry in his briefcase, the one that was to give the Germans misleading information. The document took the form of a letter from a very high-ranking officer. Sir Archibald Nye, Vice-Chief of the Imperial Staff, to Sir Harold R. L. Alexander, who commanded an Alhed Army in Tunisia under General Eisenhower.

It was a friendly and informal letter from one long-time colleague and friend to another, and was addressed to “My dear Alex” and signed, “Best of

Luck, Yours ever, Archie Nye.”

In the letter Sir Archibald appeared to be turning down certain requests that General Alexander had made for additional troops and supplies. Sir Archibald explained that these men were needed for the assault on Greece, and the letter disclosed that efforts were underway to get the Germans to think that Sicily would be the next target.

A second letter was prepared to explain Major Martin’s mission. It was signed by Lord Louis Mountbatten, Chief of Combined Operations, and addressed to Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham, Commander-in-Chief of Britain’s Mediterranean Forces. It declared that Major Martin was a specialist in the use of landing craft and barges, and that his knowledge and experience would be useful in the upcoming invasion. The letter contained references to make the Germans believe that Sardinia, the large island directly south of Tunisia, might be the target for the invasion.

An airtight container was built to hold the body. It looked something like a torpedo with flattened ends. One end was fitted with a lid.

Major Martin was loaded into the sheet metal container. Then it was filled with dry ice. As the dry ice melted into carbon dioxide, it would prevent oxygen from entering the container. This would slow the decomposition of the body.

The container was trucked north to Greenock, not far from where the Seraph lay at anchor. A motor launch ferried the container to the submarine. Early in the evening of April 19, 1943, the Seraph sailed for Spain.

Comdr. Montagu waited anxiously for news from the submarine. A week went by. Then Naval Intelh-gence headquarters received a coded message from the Seraph reporting that Major Martin had been successfully launched.

Comdr. Montagu later learned that the Seraph had surfaced off the Spanish coast not far from the mouth of the Huelva River in the pre-dawn hours of April 23. The steel container was hauled up onto the deck and Major Martin removed from it.

The body was wrapped in a hfe jacket, assuring that it would float. Officers checked to see that the briefcase was securely attached to Major Martin’s wrist.

Major Martin was lowered into the water. Crew members of the Seraph then shoved the empty container into the sea and sank it with gunfire. Its task completed, the Seraph submerged and moved away.

Not long after, a Spanish fisherman noticed a floating object, which turned out to be the body of Major Martin. The body was brought ashore and military officials were summoned. A Naval officer took charge of the documents and personal effects.

After being examined by a Spanish doctor, who reported Major Martin had drowned, the body was turned over to British diplomatic officials in Huelva. They arranged for a mihtary funeral and for Major Martin’s burial in the cemetery there. When Comdr. Montagu learned of this, he arranged for a wreath to be placed on the grave from Pam and the major’s family.

At the time the body had been turned over to the British, mention had been made of the briefcase and

The documents the major had been carrying. British officials demanded that the Spanish turn them over. Eventually they did.

When the documents finally reached London, Comdr. Montagu examined them. The envelope seals appeared not to have been broken, but scientific tests disclosed that the envelopes had been opened and their contents removed. Comdr. Montagu felt certain that German agents had been permitted to make copies of them.

In the early morning hours of July 10, 1943, the Allies invaded Sicily. The American task force was made up of 580 vessels and 1,124 landing craft. The British task force consisted of 795 ships and 715 landing craft. Despite their enormous size, the task forces suffered only minor losses. One admiral remarked that it was “almost magical that great fleets of ships could remain anchored on the enemy’s coast . . . with only such shght losses from an attack as were incurred.”

Some 478,000 troops—228,000 American, 250, 000 British—landed on the Sicilian beaches in the first three days. The landings met little opposition and the beach defenses were quickly overthrown.

After 39 days. Allied forces occupied all of Sicily. They later were to use the island as a springboard for their invasion of Italy. Mussolini fell from power in Italy during the fighting in Sicily.

It was not until several months after the war had ended that Comdr. Montagu learned how Major Martin had influenced the Sicihan campaign.

Documents found in the German naval archives revealed that their agents had telegraphed the con-

Tents of the letters carried by Major Martin to their superiors in Berlin. There the letters were treated with the greatest importance. The translation into German of the letter from Sir Archibald Nye to General Alexander was stamped most secret and made available to top-level German officials. Even Admiral Karl Doenitz, Commander-in-Chief of the German Navy, had initialed the letter, indicating that he had read it. Hitler learned of the documents from Doenitz.

A report that the Germans circulated with the let-

CLOSE TO HALF A MILLION ALLIED TROOPS LANDED ON SICILIAN BEACHES IN FIRST THREE DAYS OF INVASION. THEY MET LITTLE OPPOSITION. (National Archives)

Ter stated, ‘The genuineness of the captured document is above suspicion/’ Other reports gave evidence that the personal papers that Major Martin carried had been carefully inspected.

The German High Command acted on the belief that Greece and Sardinia were the targets of the Allied invasion. A newly-formed German motorized division was sent to Sardinia to reinforce Italian troops there. Another motorized division was sent across France to Greece.

The German Naval Command ordered the laying of minefields off the Greek coast. A group of German submarines was transferred from Sicilian waters to the Aegean Sea.

Even after the first landings in Sicily, the Germans still could not beheve that they had been misled. They thought the Sicihan attack was meant to divert their attention from the real invasions that were to come. A bulletin went out to German agents to be on the lookout for an Allied convoy bound for Sardinia.

The scheme concocted by Comdr. Montagu and his associates fooled the Spanish, who were working with the Germans, fooled German intelligence officers in Spain and Berlin, and fooled the German High Command. The plan even fooled Hitler.

No one knows for sure how many thousands of American and British lives were saved by Comdr. Montagu’s hoax, but one thing is certain—Major Martin served the Alhes well.

World History

World History