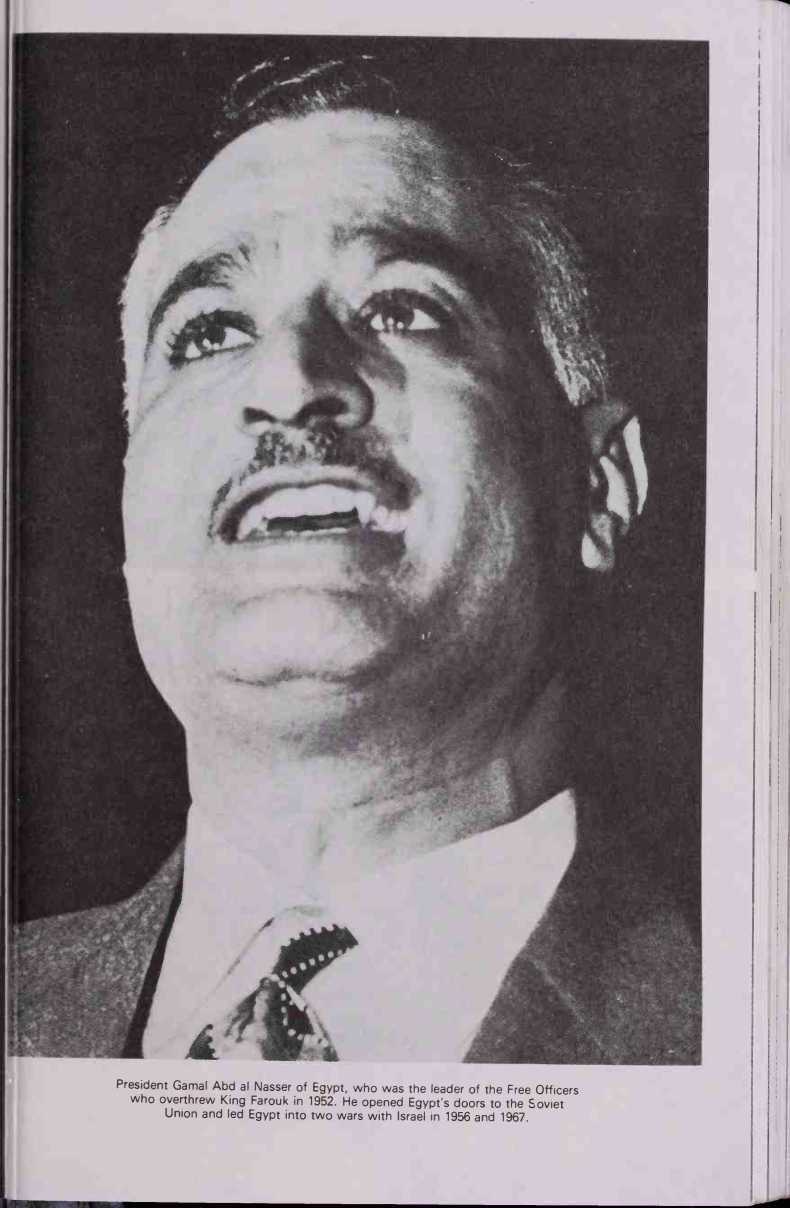

The major Arab defeat in 1948 exacerbated many of their internal problems, bringing to the fore the extreme elements and creating an atmosphere of unrest and near-revolution in many of the Arab countries. In July 1951, King Abdullah of Jordan, who had secretly initialled an agreement intended to lead to a peace accord with Israel, was assassinated, struck down by the agents of the Mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin el-Husseini, on the steps of the El Aqsa Mosque on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. (His grandson Hussein, who was to be proclaimed King of Jordan a year later, was at his side.) In Egypt, the Egyptian Prime Minister, Nokrashi Pasha, was assassinated in the aftermath of the War. The Syrian Government was overthrown by General Husni el Zaim in 1949, and he in turn was overthrown in 1951; thereafter, Syria was to be torn by frequent military revolutions. In Egypt, a group of so-called ‘Free Officers’ led by Lieutenant-Colonel Gamal Abd al Nasser seized control of the government on 23 July 1952 and sent King Farouk into exile. For a period, the officers appointed as their leader General Mohammed Neguib,

Who had emerged from the 1948 War as a popular figure, but he was soon deposed and full authority over the new republic was assumed by Nasser. (One of the leading members of the Free Officers group who participated in the revolution was Lieutenant-Colonel Anwar el Sadat, later to be the President of Egypt and the first Arab leader to sign a peace treaty with Israel.) In Jordan, moves made by the British Government to induce the Kingdom to join the Western Middle East alliance known as the ‘Baghdad Pact’ provoked riots in December 1954. This extreme reaction was brought about by an anti-Western, pro-Nasser change of direction in the Jordanian Government: Glubb Pasha and the British officers serving in the Arab Legion were dismissed summarily, and thereafter armed incursions from Jordan by fedayeen groups frequently attacked objectives in Israel.

The rise of Nasser to power in Egypt was welcomed at first by Israel. Indeed, the aims of the revolution and initial contacts with Nasser’s regime inspired hope for the future. But Nasser’s mixture of radicalism and extreme Arab nationalism, coupled with an ambition to achieve leadership in the Arab world, pre-eminence in the world of Islam and primacy in the so-called ‘non-aligned’ group of nations (which, with Presidents Tito and Nehru, he founded), gradually came to expression in a bitter, blind antagonism to Israel. It was to lead Egypt to tragedy.

In late 1955, a massive arms transaction between Egypt and Czechoslovakia was concluded, whereby Egypt received modern weapons. This, as Nasser declared, constituted a major step toward the decisive battle for the destruction of Israel. Egypt received 530 armoured vehicles (230 tanks, 200 armoured troop carriers and 100 self-propelled guns), some 500 artillery pieces, and up to 200 fighter, bomber and transport aircraft, plus destroyers, motor torpedo-boats and submarines. Thus was established the first major Soviet foothold in the Middle East. This arms agreement with the Eastern bloc was a major boost to Nasser’s ambitions. He was now establishing himself as the leading element hostile to ‘Western imperialism’ in the Middle East, and becoming a serious embarrassment to the British and French in the area. Besides supporting radical governments in Africa and backing the fedayeen raids on Israel, he was active in helping the FLN* revolutionaries in Algeria against French rule. This, however, created a bond of common interest between Israel and France, as a result of which Shimon Peres (then the dynamic Director-General of Israel’s Ministry of Defence) was able to promote various areas of co-operation between the two countries. Israel now began to receive shipments of arms from France (although sufficient only to avoid Egypt’s superiority in weaponry from exceeding four to one on the eve of the Sinai campaign).

Egypt meanwhile blocked the navigation of Israeli vessels in the international waterways of the area in violation both of the 1949 armistice agreement and of international law. In order to reach the Red Sea and maintain commercial and maritime contacts with the Far East and Africa, Israeli vessels had to navigate through the Straits of Tiran, which Egypt had blocked by installing a coastal artillery battery at Ras Nasrani. Egypt

* Front de Liberation Nationale, the Algerian revolutionary movement against the French, which was proclaimed on 1 November 1954.

Above: King Hussein of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan shakes the hand of his implacable enemy, Ahmed Shukeiri, the Palestine delegate of the Arab League, later a founder of the Palestine Liberation Organization. (UPl)

Right: President Aref of Iraq with Nasser. (UPl)

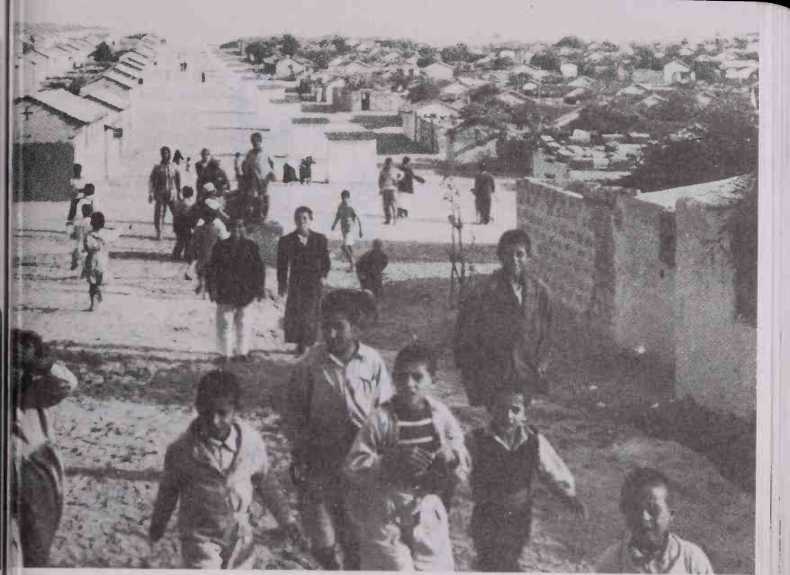

Far right, top: A refugee camp in Gaza, The Arab governments have for political reasons perpetuated this crucial problem in the Middle East, opposing any attempt to dissolve the camps and resettle the refugees.

Far right, below: The '101 Unit' of the IDF was specially created to combat fedayeen raids. Its commander was Ariel Sharon (left), later to become a major-general and commander of the southern front in 1973; today he is Israel's Minister of Defence, On his left is Lieutenant-General Moshe Dayan, then Chief of G Branch (Operations) of the IDF,

Above: An Israeli pilot climbing into a French-manufactured A British-manufactured Archer self-propelled anti-tank gur

Mystere IV A single-seat fighter - an aircraft that played a of Second World War vintage, captured from the Egyptiar

Key role in the Sinai Campaign, (Zahal-Bamahane) Below: In the background is a Soviet-built T34/85 tank. (GPO)

Had also barred all passage by Israeli vessels through the Suez Canal — despite a Resolution of the United Nations Security Council in 1951 censuring Egypt’s policy on this issue. But, even after this Resolution, Egypt, aided politically by the Soviet Union, extended the maritime limitations, impounded Israeli vessels, cargo and crews.

In the course of negotiations with Great Britain, Nasser negotiated the withdrawal of British troops from the Suez Canal Zone, where they had been stationed for over eighty years by treaty. He was also negotiating with the United States Government and with the British Government for a loan from the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development to finance the construction of a dam on the River Nile above Aswan. This would supply electricity, control the Nile floods and by irrigation increase considerably the area of arable land in Egypt. At the same time, he conducted parallel negotiations on this project with the Soviet Union. But his attempt to play off West against East on this issue aroused the wrath of the United States Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, who in July 1956 withdrew the American offer to finance the dam. Infuriated, Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal on 27 July 1956 by seizing control from the Suez Canal Company, in which the British Government held a majority share, and abrogating the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty. Seeing the seizure of the Canal as a threat to their strategic interests — including their oil-supply routes — the British and French began to prepare contingency plans. Forces were moved to Malta and Cyprus in the Mediterranean in preparation for the seizure of the Canal Zone and, indirectly, to bring about Nasser’s downfall. Such a campaign, whilst objectively-speaking independent of the local Arab-Israeli problems, naturally had its implications — a factor that undoubtedly contributed to the decisionmaking process prior to the start of the campaign.

By this time, the Israeli leadership had reached the conclusion that Nasser was heading for an all-out war against Israel. This could be the only explanation for the joint military command established in October 1955 between Egypt and Syria (to be expanded in 1956 to include Jordan). The blockade of the Suez Canal and the Gulf of Aqaba was part of an allout economic war against Israel, while the fedayeen incursions into Israel were becoming more frequent and exacting greater numbers of casualties — some 260 Israeli citizens being killed or wounded by the fedayeen in

1955. The Egyptians would very rapidly absorb the weapons supplied by the Soviet bloc. It was clear that Israel could not allow Nasser to develop his plans with impunity. Accordingly, in July 1956, David Ben-Gurion decided that he had no option but to take a pre-emptive move, and gave instructions to the Israeli General Staff to plan for war in the course of

1956, concentrating initially on the opening of the Straits of Tiran.

Israel meanwhile mounted diplomatic efforts to expedite the supply of

Arms from France. According to Moshe Dayan, the Chief of Staff at that time, the Israeli military attache in Paris cabled on 1 September 1956, advising him of the Anglo-French plans against the Suez Canal and informing him that Admiral Pierre Barjot, who was to be Deputy Commander of the combined Allied forces, was of the opinion that Israel

Should be invited to take part in the operation. Ben-Gurion’s instructions were to reply that in principle Israel was ready to co-operate. An exploratory meeting took place six days later between the Israeli Chief of Operations and French military representatives, while Shimon Peres continued talks in Paris with the French Minister of Defence, Maurice Bourges-Maunoury. At the end of the month, an Israeli mission headed by Foreign Minister Golda Meir, and including Peres and Dayan, met a French mission that included the French Defence Minister and the French Foreign Minister, Christian Pineau. As the preparations were set afoot to strike at Egypt, Franco-Israeli meetings became more frequent. Then, on 21 October, at the invitation of the French, Ben-Gurion flew to Sevres in France, accompanied by Shimon Peres and Moshe Dayan. At these negotiations, in which the French Prime Minister, Guy Mollet, participated, they were joined by a British mission consisting of the British Foreign Minister Selwyn Lloyd and one senior official. After much discussion, during which Ben-Gurion was very hesitant because of his innate lack of trust in the British, the plan was arranged in such a way that Israel’s first moves would not be interpreted as an invasion, and its forces could be withdrawn should the British and French allies not fulfil their part of the agreement.

A further factor affecting considerations was the way in which both the United States and the Soviet Union were preoccupied in such a manner (or so it was estimated) as to limit their freedom of action at the time. The United States was in the throes of a presidential election, during which it was assumed that President Eisenhower would not take any vital international decision that might prejudice his chances of re-election. Similarly, the Soviet Union was busy during the three months prior to the campaign, quelling the national urge for liberalization that had begun to come to expression in Poland and Hungary.

By October 1956, the Egyptian threat to Israel had taken on an increasing active form. Fedayeen raids reached an all-time high, in both intensity and violence, and the Israeli reprisal policy did not supply any final, secure or convincing answer. This and the prevailing global situation placed Israel in a position in which it had to take advantage of the circumstances in order to break the Egyptian stranglehold on its commercial sea routes and along its border areas. The aims were to be threefold: to remove the threat, wholly or partially, of the Egyptian Army in the Sinai; to destroy the framework of the fedayeen; and to secure the freedom of navigation through the Straits of Tiran. Only thus would Israel place itself in a comfortable bargaining position for the political struggle that would undoubtedly ensue.

World History

World History