At 11.00 hours on 5 June 1967, the Jordanian Army launched a barrage of artillery and small arms fire from positions along the winding armistice line against targets inside Israel, including the cities of Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, and its forces crossed the border south of Jerusalem, occupying the United Nations observers’ headquarters in Government House, supposedly a demilitarized zone.8

In charge of the Israeli Central Command was Major-General Uzi Narkiss. He had served with distinction with the Palmach, and had in fact commanded the battalion that had broken into the Old City at the Zion Gate in the War of Independence in 1948. Major David Elazar (‘Dado’) commanded the company in his battalion that actually broke in. A graduate of the French Ecole de Guerre, General Narkiss, a short, slightly-built man, combined a sharp analytical mind with a keen military understanding. He had served as Deputy Director of Military Intelligence and also as Defence Attache to France.

Narkiss ordered the Israeli artillery to reply to the Jordanian bombardment, and a force of the 16th Jerusalem Brigade was sent to oust the Jordanians of the ‘Hittin’ Brigade from Government House. Units of the 16th Brigade stormed the area, relieved the United Nations personnel who had been cut off inside, and the impetus of the attack continued towards the village of Zur Baher, lying astride the main Hebron-Jerusalem road — which, in fact, linked the Hebron Hills and the area of Hebron with the rest of the Jordanian kingdom. The Jordanians in the Hebron Hills would now have only secondary roads and mountain tracks as a means of communication with the Jerusalem area and with other parts of the West Bank. The action of the Jerusalem Brigade had thus cut off the area of the Hebron Hills, which was to have been a jumping-off ground for the Jordanian forces in the direction of Beersheba and the Negev, with a view to linking up with the Egyptian forces that were supposed to be advancing across the Negev.

With Jerusalem again under bombardment from the guns of the Arab Legion, and Ramat David airfield and the centre of the city of Tel Aviv being shelled by the long-range Jordanian guns, orders were given by the Israeli General Staff to General Narkiss to move over to the offensive. As part of the plan to isolate Jerusalem from the bulk of the Jordanian Army to the north. Colonel Ben Ari’s 10th (‘Harel’) Mechanized Brigade was ordered to move up into the Jerusalem Corridor to break through the Jordanian lines in the area of Maale Hahamisha and to seize the mountain ridge and road connecting Jerusalem with Ramallah. This area is the key to the control of the Judean Hills and Jerusalem, for it overlooks the

Descent to Jericho and controls all approaches to the city. (This was the area that Joshua, in his campaign to occupy the hills of Judea, saw as his first priority when he crossed the River Jordan; and it was also the area that the British 90th Division in the First World War occupied before Allenby took Jerusalem.) The ‘Harel’ Brigade under Ben Ari, who had achieved renown at the head of the 7th Armoured Brigade in the 1956 Sinai Campaign, advanced towards the central region up between three mountainous spurs abutting the Jerusalem Corridor at Maale Hahamisha — Radar Hill, Sheikh Abd-el-Aziz and Beit Iksa. Indeed, Colonel Ben Ari was back again fighting over familiar territory. In 1948, he had been a company commander in the Palmach ‘Harel’ Brigade that had fought over the area north of the Jerusalem Corridor. The strategic Radar Hill had been taken by the Arab Legion in fierce fighting at the time. In vain, Ben Ari had led his company in five counterattacks on the position — and for the ensuing nineteen years this dominant feature, which in effect controlled the Jerusalem road to the coast, had been in the hands of the Arab Legion.

The area chosen by Ben Ari was difficult mountainous terrain, with well-fortified positions of the Arab Legion covering all approach routes. Ben Ari’s forces advanced up the main Jerusalem road from the coast and, without any pause, turned northwards along the three parallel axes and stormed the Legion positions, the tanks neutralizing the Arab bunkers at point-blank range and the armoured engineers and infantry overcoming them. This operation began in the afternoon hours of 5 June; by midnight, after hours of heavy fighting, the breakthrough had been achieved and, in the morning of 6 June, Ben Ari’s brigade was well established on the strategic ridge (facing the hill at Tel El-Ful overlooking Jerusalem, on which a palace for King Hussein had been in the course of construction). The Brigade now controlled an area with roads leading to Jericho in the east, to Latrun in the west, to Ramallah in the north and to Jerusalem in the south. Parallel and simultaneous to this operation, units of Yotvat’s infantry brigade from the Lod area had occupied the Latrun complex, putting to flight the Egyptian commandos who had begun to operate from the area against Israeli targets. Thus, for the first time after so many bloody battles that had failed in the War of Independence, Latrun was in Israeli hands, and the Latrun-Ramallah road was under Israeli control.

King Hussein’s air force had attacked targets in Israel that morning at

11.00 hours, its main target being a minor Israeli airfield at Kfar Sirkin near Petach Tikva. In attacking. King Hussein was a victim not only of his own folly but of the duplicity and false reporting of his Arab allies. He had received false information, cabled by Field Marshal Amer from Egypt to the Egyptian General Riadh early in the morning, advising that 70 per cent of the Israeli Air Force had been wiped out; he had also been advised by Nasser of the failure of the Israeli attack and of the armoured advance of the Egyptians across the Negev towards the Hebron Hills. The Syrians, who let him down, as he described quite vividly in his memoirs on the war, and who despite all their promises did not send any forces to support him over a period of a week, announced that their air force was not yet ready

To operate. The Iraqis advised him that they had already taken off and bombed Tel Aviv, causing much destruction there — a claim that was completely false. King Hussein, for his part, launched his aircraft against Israel in an unsuccessful attack. Thereupon, the Israeli Air Force, having eliminated most of the Egyptian Air Force, directed its attention to the Jordanian Air Force, attacking the Jordanian bases at Mafraq and Amman. Jordan’s Air Force, numbering some 22 Hawker Hunters, was wiped out and Jordan was left without air support in the ensuing fighting.

This allowed the Israeli Air Force to focus its attention on close ground support. Since orders were that on no account should air attacks be mounted in the vicinity of Jerusalem, Israeli Air Force strikes were directed towards the Jordanian reserves in the Jordan valley and the interdiction of forces moving along the Jericho-Jerusalem road to reinforce the Jordanian units battling in Jerusalem. The Israeli air attacks forced the Jordanian West Bank HQ to withdraw to the east of the River Jordan. The road from Jericho to Jerusalem lay strewn with the tanks of the Jordanian 60th Brigade, which had tried in vain to move up to the Jerusalem area.

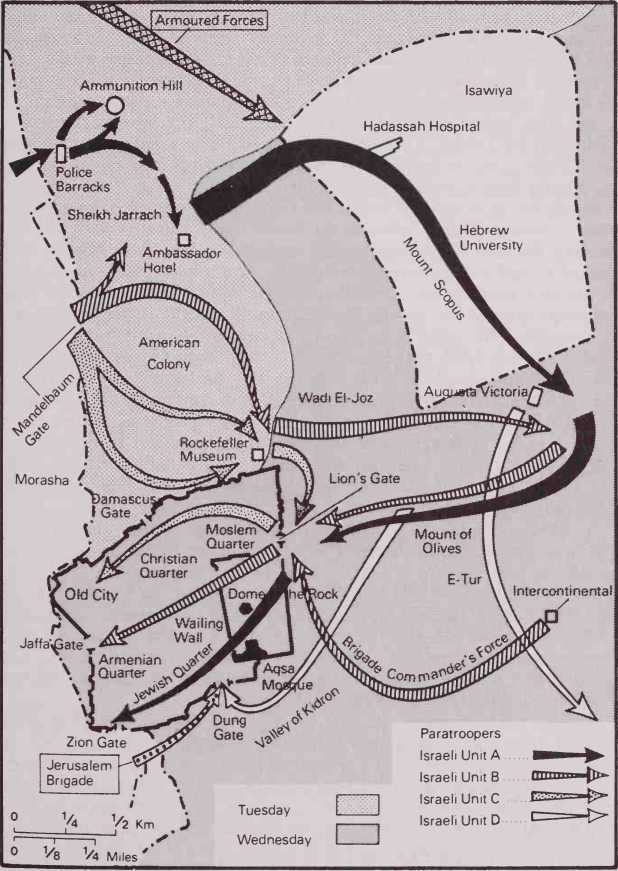

Colonel ‘Motta’ Gur’s 55 Parachute Brigade had now been assigned fully to General Narkiss’s Command. Its mission would be to break through in the built-up area north of the Old City of Jerusalem at Sheikh Jarrach, the Police School and Ammunition Hill. This was the area that controlled the road leading up to the Mount Scopus enclave, where a small force of 120 Jewish policemen had been isolated for years (and only supplied under the auspices of the United Nations). Such a move would also complement Ben Ari’s operation and would doubly sever the link between Ramallah and northern Jerusalem leading into the Old City. The Arab Legion was only too aware of the bitter battles that had been fought over this area in 1948 and of the strategic importance of these districts in northern Jerusalem. Accordingly, over nineteen years they had constructed a vast complex of most formidable defence works with the purpose of ensuring that no Israeli attack could break the link between the area of Ramallah and the Old City of Jerusalem. The buildings and positions in this area were honeycombed with a complex of reinforced concrete defences, in many cases several stories high, all interconnected by deep trenches and protected by minefields and barbed wire.

Since the conclusion of hostilities in 1948, Jerusalem had been divided between two warring elements: barbed-wire in profusion, fortifications, trenches and battlements cut through the city, and across them each side watched the other warily. The western part of the city was predominantly Jewish, with over 100,000 inhabitants, and was the tip of the Israeli salient connected to the coast by the Jerusalem Corridor. The city itself was surrounded on three sides by Jordanian military positions, which controlled the approaches from the high ground on each side. In particular, the Jordanian Arab Legion threatened the Corridor, primarily at Latrun, which it had held since the battles of 1948, and from the high ground north of the Corridor covered the road linking Jerusalem to the coastal plain. The Arab part of Jerusalem was held by the Arab Legion

Centring in particular on the historic Old City, with its shrines and holy places revered by all three major religions, and also the eastern, predominantly Arab part of Jerusalem. There were two enclaves in Jerusalem that added to the military problems of the commanders there. The first was Mount Scopus, an Israeli enclave on the site of the Hebrew University and the Hadassah Hospital; it had been completely surrounded in 1948, but had held out successfully against all Arab attacks. The second enclave was the area of Government House, which had been the residence of the British High Commissioner of Palestine and had continued after the British withdrawal as the headquarters of the United Nations Truce Supervision Organization following the war and the signing of the armistice agreement. It was situated to the south of the Old City on a spur known as the Hill of Evil Counsel, jutting eastwards and controlling the road linking Jerusalem and Bethlehem, which had been built by the Jordanians.

Jerusalem was defended by a very heavy concentration of Jordanian forces. The responsibility for the defence of the Old City lay with the 27th Infantry Brigade of the Arab Legion under the command of Brigadier Ata Ali. The area of Ramallah north of Jerusalem was held by the ‘El Hashim’ Brigade, which detached some forces to the northern suburbs of the city. One battalion of tanks of the 60th Armoured Brigade was stationed just outside Jerusalem across the Kidron valley. The ‘Hittin’ Brigade, which was responsible for the Hebron area south of Jerusalem, had also detached a battalion to be responsible for the area between Jerusalem and Bethlehem. Surprisingly enough, there was no Jordanian central command for the whole area of the City of Jerusalem.

When General Narkiss was finally given permission to commence hostilities after the Jordanian forces had opened fire and taken Government House, he set into motion the contingency plans of the Israel Defence Forces. These envisaged a move by the Jerusalem Brigade under command of Colonel Amitai to seize an area to the south of the city, which would cut the communications between Bethlehem and Jerusalem and threaten the Jordanian communications from Jerusalem to Jericho. Colonel Ben Ari’s Mechanized ‘Harel’ Brigade was to seize the high ground and the ridge between Jerusalem and Ramallah, thus effectively cutting off Jerusalem from both Jericho and Ramallah. The main effort against the eastern part of the city and the Old City would be made by Colonel Gur’s parachute brigade. One of the outstanding qualities of the Israel Defence Forces was emphasized by the flexible manner in which Gur’s brigade, poised to parachute into El-Arish or Sharm El-Sheikh, had its mission changed at a moment’s notice and was, literally in a matter of hours, moving up to Jerusalem. Its commanders had moved ahead and were reconnoitring the built-up area far from the desert sands where they had anticipated operating, and planning to overcome heavily-fortified positions in one of the most difficult types of military operation — fighting in built-up areas.

During the afternoon of 5 June, after the Jordanian Air Force had been wiped out, Israeli aircraft repeatedly attacked Jordanian positions around

Jerusalem, and particularly all reinforcements on the road from the River Jordan at Jericho towards the city. All Jordanian line communications had been destroyed and, by evening, their main radio transmitter at Ramallah had been put out of action. In the meantime, the headquarters of the West Bank forces had been forced by the Israeli air activity out of

The Battle for Jerusalem, 5-7 June 1967

The West Bank, and had moved over to the East Bank of the River Jordan. Brigadier Ata Ali, commanding the Jordanian 27th Brigade in the general area of Jerusalem, desperately pleaded for forces to reinforce his troops, which were now fighting against heavy odds, and soon elements of the 60th Armoured Brigade and an infantry battalion began to move up after dark along the Jericho-Jerusalem road. However, the Israeli Air Force illuminated the road with flares and then proceeded to destroy the relief column, which was wiped out. The Jordanians were aware of the arrival of Gur’s forces in Jerusalem, and realized that a major offensive would now take place. Efforts were therefore made to send up infantry reinforcements by desert tracks and side roads in order to avoid aerial interdiction.

An hour before midnight on 5/6 June 1967, the historic battle for Jerusalem was joined. A pre-prepared plan of artillery and mortar fire was set in motion and, as searchlights from the western part of Jerusalem and the Mount Scopus enclave focused their beams on target after target, a numbing concentration of Israeli point-blank fire reduced Arab position after position. Shortly after 02.00 hours, Gur’s paratroopers, led by artillery fire and the reconnaissance unit of the Jerusalem Brigade and backed by tanks of the Jerusalem Brigade, advanced across no-man’s land in the area between the Mandelbaum Gate and the Police School. One battalion attacked the heavily-fortified complex of the Police School and Ammunition Hill, while in the north a second battalion advanced into the Sheikh Jarrach district. The Jordanian forces fought fiercely. After Gur’s forces had negotiated the fields of mines that the Jordanians had laid on the approaches to the positions, a series of close-combat battles developed as Israeli forces worked their way along the trench positions, moving from room to room, clearing bunker after bunker, fighting on the roofs and in the cellars. For four hours, this desperate see-saw battle was fought, with the troops of both sides fighting incredibly bravely. The battle on Ammunition Hill has become part of the military saga of Israel.

As dawn approached, Gur threw in his third battalion to the southern sector at Sheikh Jarrach, together with tanks of the Jerusalem Brigade. It fought its way towards the area of the Rockefeller Museum facing the northern sector of the Old City Wall, in the area of the Damascus Gate and Herod’s Gate. By mid-morning, the area had been cleared, and Israeli forces controlled the area between the city wall and Mount Scopus. Communications were now reopened with the besieged enclave, and the paratroopers were established in the valley below Mount Scopus and the Augusta Victoria Hill facing the Old City wall.

Parallel to these operations, Ben Ari’s ‘Harel’ Brigade had taken Nebi Samuel and was consolidating along the Jerusalem-Ramallah road. A battalion of the Jordanian 60th Armoured Brigade that had been stationed in the Jerusalem area launched a counterattack. After a short, fierce battle near Tel El-Ful in which they lost several tanks, the Jordanians withdrew, and Ben Ari’s forces continued towards Shuafat Hill, north of Jerusalem.

Thus, by mid-morning on Tuesday 6 June, units of the 16th Jerusalem Brigade were holding Zur Baher south of Jerusalem, cutting-off the Hebron Hills from Jerusalem; Gur’s paratroopers were poised between

Mount Scopus and the Old City; and Ben Ari’s armoured force was in control of the northern approaches from Ramallah to the city. Brigadier Ata Ali’s brigade was now divided up into three isolated units — in the Old City, on Shuafat Hill and in the general area of Augusta Victoria, which was on the ridge between Mount Scopus and the Mount of Olives. There was a small unit also in the Abu Tor area, just south of the Old City’s walls overlooking the Jerusalem railway station. He was advised by King Hussein personally that efforts would be made to relieve Jerusalem, and he accordingly decided to hold on and fight. Meanwhile, the Qadisiyeh Infantry Brigade that was concentrated in the area of Jericho began to move towards Jerusalem along the mountain roads and tracks. En route, however, the Brigade was spotted by the Israeli Air Force using flares, and heavy casualties were inflicted on it in repeated attacks. The timetable of the relief column was so disrupted by these attacks that by the time it approached Jerusalem it was already too late to be of any assistance to the Jordanian forces in the Old City.

World History

World History