But Rommel was not working office hours. He did not wait until 8 a. m. As dawn broke, his infantry of the 6. Rifle Regiment were trying to force a crossing at Bouvignes and getting badly shot up by French artillery and small-arms fire as fast as they put their inflatable boats into the river. They persevered in the face of casualties. By the time Rommel himself arrived at the riverbank, one company was already across.

Noting the absence of smoke that would screen his men from the enemy fire, Rommel ordered some houses to be set ablaze so that smoke would pour down the valley. The crossing attempts continued. Rommel ordered tanks and artillery support and then went back for a meeting with Kluge, the commander of the Fourth Army, and with his panzer corps commander, Hoth, both of whom had arrived at Rommel’s HQ to watch the progress of the battle.

Both Kluge and Hoth were at fault for requiring Rommel’s presence at headquarters. In such critical circumstances the divisional commander must be left to get on with his job or the higher ranks should go to the place where he is.

By the time Rommel had returned to Dinant, the crossing attempt had come to a complete standstill. Punctured rubber boats lined both sides of the river, and his officers had ceased to urge their men out from the cover behind which they sheltered from fierce French fire.

Partly due to the effect that the presence of the divisional commander had upon the men, and more especially upon the junior officers who led them, a few Germans managed to get across the river.

The cumbrous communications system of the French Army was already playing a part in the battle. The telephone was subject to delays and even the corps commanders had no clear picture of what was happening. The French counterattack, planned for 8 a. m. that morning, was canceled. At the battlefront it became apparent that only a sharp riposte would dislodge the Germans, for although they had no tanks or artillery across the river, infantry were filtering along the bank. By 10 A. M. Bouvignes was in German hands. At noon the German foothold was about 3 miles wide and 2 miles deep. By now the artillery support that Rommel had requested was beginning to arrive. So were some of the PzKw IV tanks, with 7.5 cm guns, that could fire back at the French positions.

Rommel’s lengthy and frequent visits to the front enabled him to make instant decisions about tactics, forcing subordinate commanders to show similar energy and initiative with their units and inspiring lower ranks to extraordinary feats. His operations staff remained in the rear, and he kept in contact with them by means of radio and twice-daily conferences with his lA, the operations officer. Said one German officer:

In all the war in France from frontier to Channel, Rommel never saw his Chief of Staff personally. Never! He only had with him, next to the tank of my regimental commander, two armoured reconnaissance cars with long-range radio. The one car was in contact with all the troops of his own division. The other car was for contact with the corps, the Army and often to the air force.40

Rommel was criticized by his seniors for spending too much time at the front, but he had never commanded a panzer division before and needed to see the problems of the advance at close hand.

Now Rommel went even further. He took command of the second battalion of his 7. Rifle Regiment, urging them forward to get their boats into the water. Climbing into one of the boats, he personally led the assault on the far bank.

It was while Rommel was on the west bank of the Meuse that some French tanks were sighted. Without tanks or antitank guns, the Germans had no alternative but to engage them with small-arms fire. Rommel ordered even flare pistols to be fired at them. Perhaps believing the flares to be the sighting rounds for an artillery battery, the French tanks moved away.

A cable ferry had been built under covering fire provided by the guns of the PzKw IV tanks. The engineers moved twenty antitank guns to the west bank by noon of 13 May. Rommel, having returned from the far bank, told his engineers to convert the 8-ton pontoon into a 16-ton unit to ferry light tanks and armored cars across. The very first trip took Rommel himself across the Meuse for a second time, together

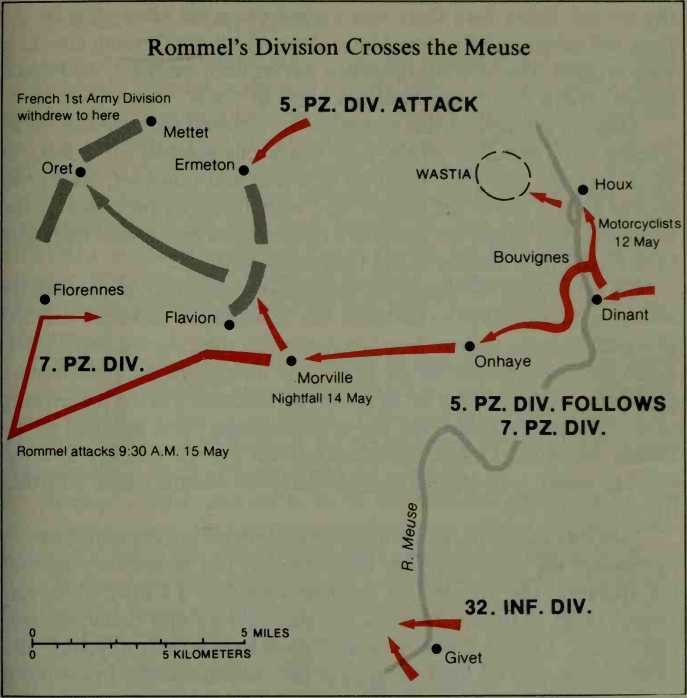

MAP i6

With his eight-wheel armored car. But it was a slow business, for here the river was 120 yards wide, twice the width of the river at Guderian’s Sedan sector.

The cable ferry was under constant fire and at least one tank went to the bottom of the river. When darkness fell, the engineers were able to work with less interference, and by dawn of the next day, 14 May, Rommel had moved fifteen tanks to the west side of the river. Local people told me that access ramps at the marble quarry were used to get the tanks up to the heights by the quickest possible route. And several local people remembered seeing the tank that had toppled into the water.

It was the Germans who had got up to the heights of Wastia that most worried the defenders. This plateau controlled all the surrounding terrain. From here there was a view down the steep cliffs to the river and across to the eastern bank, along which the German attackers were arrayed. The morning operation having been canceled, the French decided that a counterattack would begin at 1 p. m.

German triumphs in this campaign have caused their military recklessness to be hailed as genius, their dangerous gambles to be thought of as miracles. The great columns of armor and transport, trailing as frail as threads across the French rear, were in theory protected by the Luftwaffe. But in fact the Luftwaffe commanders interpreted their role in as foolhardy a manner as did the panzer generals.

To overwhelm the enemy air forces and to concentrate dive bombers and fighters enough to pulverize the defenders, it had been decided to concentrate the Luftwaffe in one sector at a time. As the French prepared the counterattack on the heights of Wastia, the bulk of German air power was over Sedan far to the south. But such was the inadequacy of the French Air Force that the small covering force assigned to the Dinant sector on 13 May dive-bombed the French infantry and the reconnaissance with enough vigor to delay the counterattack a further five hours to 6 p. m.

Motorized infantry and tanks to the north of Wastia were ordered to dislodge the Germans from those heights, but before they moved, the operation was retimed for the following day, 14 May. However, French tanks to the south of the Germans did go into battle. As twilight came, French armor attacked the German motorcyclists and gained possession of the high ground that dominated the bridgehead, the river, and the crossing places.

But the French supporting infantry failed to arrive, and without them the tanks could not properly consolidate their gains. After dark the tank crews fell prey to the fears that all unprotected tank forces have at night in the presence of enemy infantry. So the French tanks withdrew to their starting place and let the Germans reoccupy the vitally important high ground.

The bridging unit of Rommel’s division was now provided with a perfect opportunity to start work, except that all its bridging tackle had already been used on the first day of the advance. With that ruthlessness he was already displaying in battle, and secure in the personal support of Hitler, Rommel simply helped himself to the bridging tackle of his neighboring S. Pz. Div. He brushed aside protests from the commander of that division. General Max von Hartlieb, and said that he was going to make sure that his division was first across the Meuse.

World History

World History