The Egyptian Command prepared to break the stalemate. Having withdrawn and redeployed its forces in the area along the coast south of Beit Hanun, concentrating primarily in the area of Gaza-Rafah, it planned to launch an attack from the Gaza area to relieve the Faluja pocket. As a prelude to the operation, Egyptian columns occupied a number of dominating points, particularly in the south-west. Very heavy fighting took place and, in a series of counterattacks on 5 December, the Israeli forces succeeded in occupying a number of strategic positions along the Gaza front-line in what was known as Operation ‘Assaf, units of the 8th Armoured Brigade and ‘Golani’ Brigade fighting-off heavy infantry and armoured Egyptian attacks. As a result, the Israeli line was strengthened and much improved.

Late in November, the Israeli forces had also extended their control to the east of Beersheba, across the desert towards the Dead Sea and down Wadi Arava, running south along the Jordanian border, thus relieving the southern Dead Sea potash plant at Sdom which had been cut off for well-nigh six months. (This area, on the shores of the Dead Sea, included Masada, scene of the heroic last stand of the Jews in their uprising against the Romans, in ad72.)

Meanwhile, political pressure was mounting in the United Nations Security Council to force Israel to withdraw to the lines of 14 October — which would mean allowing the Negev to be cut off again. This political pressure, in which Britain played a major role, coupled with the Egyptian moves towards Faluja (which led to the eruption of a series of battles along the Gaza front), convinced the Israeli Command that it was essential to drive the Egyptians out of the country and to remove the threat that an Egyptian concentration in the Gaza area would constitute against the security of the Negev and against Israeli security in general. Above all, the Israelis were conscious of the fact that the British Government refused to reconcile itself to the incorporation of the Negev in Israel; indeed.

Bernadotte’s plan to allocate the Negev to the Arabs in exchange for Galilee was still an option favoured by some of the Western powers. Accordingly, the Government of Israel decided to mount an additional military operation in the Negev designed to destroy the invading Egyptian forces and to create a military situation that would force the Egyptians to come to the negotiating table.

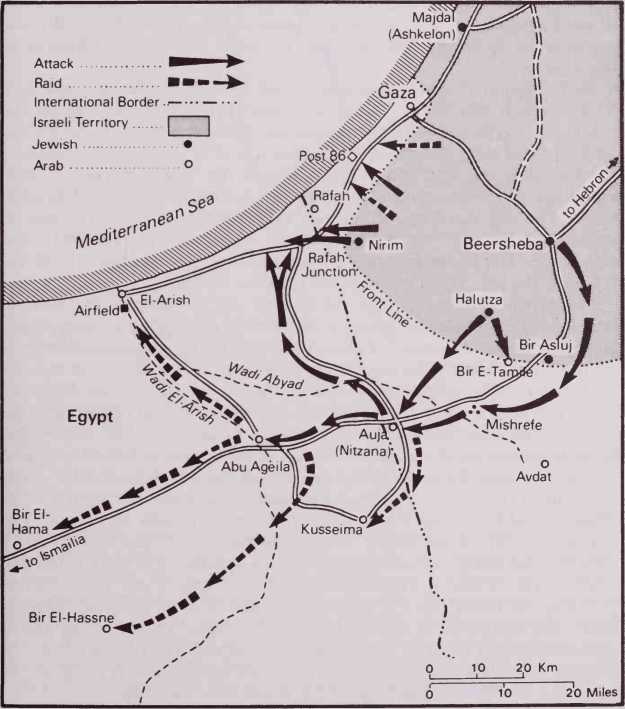

The five Egyptian brigades that now comprised the Egyptian expeditionary force, were dispersed as follows: one brigade of approximately 4,000 men besieged in the Faluja pocket; two reinforced brigades in the Gaza area; and one brigade in the area around Abu Ageila and El-Arish. There were also approximately 2,000 men, remnants of the Moslem Brotherhood battalions, still isolated in the Hebron-Bethlehem area. Thus, the Egyptian forces in Palestine were deployed in a wide arc, with the western arm sweeping from the Gaza area southwards to the area of El-Arish and Abu Ageila, and the eastern arm northwards from Abu Ageila to Bir Asluj. The main concentration of Egyptian forces was in the Gaza area, to the defence of which the Egyptian Command revealed considerable sensitivity. It was clear to Allon that a head-on attack against Gaza would be a very costly venture. As he saw it, the key to bringing about the collapse of the Egyptian dispositions would be to cut the lateral communications between the eastern and western forces. The concept — Operation ‘Horev’ — was to strike with this aim in view, to roll back the forces on the eastern road from Bir Asluj southwards and then, in a broad sweep into the Sinai Desert, to close in on El-Arish from the south and thus cut off the entire Egyptian force from its sources of supplies and reinforcements.

The forces at the disposal of the southern front commander for Operation ‘Horev’ consisted of five brigades: the 8th Armoured Brigade, commanded by Yitzhak Sadeh; the ‘Negev’ and ‘Golani’ Brigades and the ‘Harel’ Brigade; which had been moved south from the Jerusalem Corridor. The ‘Alexandroni’ Brigade continued to besiege the Faluja pocket. The Israeli Command sought a way to avoid committing forces to potentially costly operations against one strongly-held Egyptian position after another, for the Egyptians held a series of strongpoints in the area of Bir Asluj, particularly at Bir E-Tamile and Mishrefe to the south of Bir Asluj, on the road to El Auja. The Egyptian positions were deployed along the main road connecting El Auja and Beersheba — but the Israeli Command was aware of the existence of the remains of an ancient Roman road which would bypass them, running as it did almost in a straight line from Beersheba to El Auja. It had been covered by the sands over the centuries and would require considerable repairs to render it usable, but an advance along this road would bypass all the Egyptian positions in the area of Bir Asluj and cut their lines of communication to El Auja. In order to divert Egyptian attention from the activity engendered by the forces engaged in repairing the Roman road, and to mislead the Egyptians as to the direction of the principal Israeli effort, a major assault by ‘Golani’ forces was directed against the Gaza area at Hirbet Main. The ‘Golani’ troops were ordered to hammer a wedge into that area to prevent the

Egyptians from using the main coastal road. In the east, the 8th Armoured Brigade, supported by a battalion from the ‘Harel’ Brigade, would capture El Auja, and follow-up in the direction of Abu Ageila in the Sinai Peninsula. Furthermore, units of the 8th Armoured Brigade were to cut the lateral road from Rafah to El Auja and, simultaneously, two battalions of the ‘Negev’ Brigade were to capture the Bir E-Tamile and Mishrefe strongpoints astride the main road north of El Auja. An air and naval bombardment of Egyptian bases and concentrations would add to the pressure.

On 22 December, in the midst of a heavy downpour of rain in the coastal area and a violent sandstorm in the desert to the east. Operation ‘Horev’ was launched. A battalion of the ‘Golani’ Brigade surprised and

Operation 'Horev', 22 December 1948 to 8 January 1949

Captured Hill 86 controlling the Gaza-Rafah road. The Egyptians mounted a concentrated counterattack with armour, artillery and halftracks mounting flame-throwers, forcing the ‘Golani’ unit to withdraw under heavy pressure. However, the operation had the effect of concentrating Egyptian attention on this sector. Air attacks were mounted against the Egyptians in the western sector only, and naval units shelled Gaza. The Egyptians were by now convinced that the main Israeli effort was to be directed against their forces nearest the coast. Meanwhile, Israeli engineers were working around the clock, moving the sand that had accumulated over the old Roman road (known as the ‘Ruheiba trail’) and laying wire netting on it. By 25 December, an armoured force was able to move gingerly along the ancient road. Simultaneously, a commando unit executed a broad sweep into the eastern desert, emerging from the east to capture the Mishrefe stronghold, thus severing the lines of communication of the Egyptian forces based on Bir Asluj. A unit of the ‘Negev’ Brigade captured Bir E-Tamile, the defenders of which withdrew northwards to Bir Asluj.

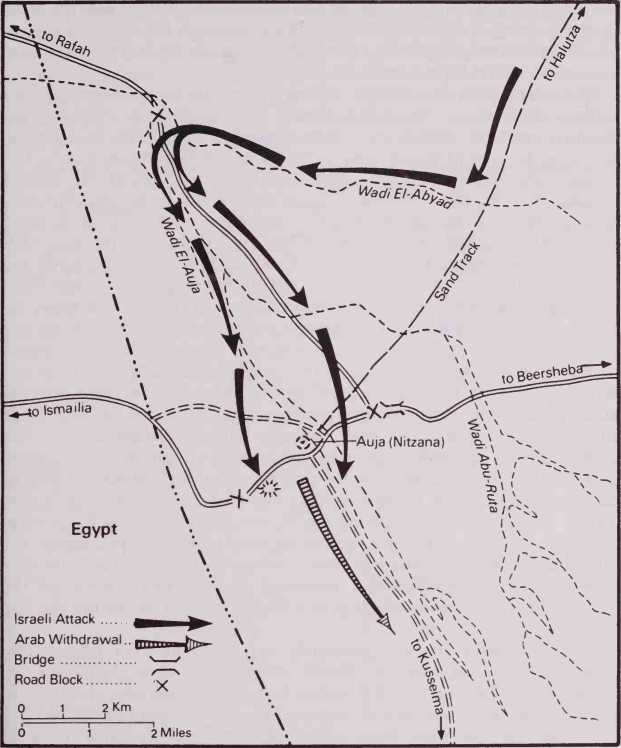

The armoured brigade operation against El Auja did not succeed until 27 December. Parallel to this, the ‘Negev’ Brigade moved against the remaining Egyptian positions between Bir Asluj and El Auja, which cut off Beersheba from El Auja. By the afternoon of 27 December, the capture of these positions had been completed and the ‘Negev’ Brigade moved along the Beersheba-Auja road, linking-up with the armoured brigade before the day was over. The entire Beersheba-Auja road was now in Israeli hands, and the first phase of Operation ‘Horev’ had been completed. The Egyptian eastern front had collapsed completely, all the forces in the area either being taken prisoner or fleeing.

The extent of the Egyptian defeat was not yet appreciated abroad, because the Egyptian Government persisted in misleading its own people with false claims of victory. Political pressure on Israel had therefore not yet mounted. At the same time, it was clear that this new situation must be exploited to take advantage of the confusion into which the Egyptian camp had been thrown and to prevent the restabilization of the Egyptian forces in the Sinai Peninsula. On the night of 28 December, the ‘Negev’ Brigade, supported by the tank battalion of the armoured brigade, crossed the border into Sinai with the mission of taking Abu Ageila. After overcoming resistance at Um-Katef, the commando battalion of the ‘Negev’ Brigade entered Abu Ageila without encountering opposition. The next day, a unit of the ‘Negev’ Brigade advanced northwards to El-Arish with the tank battalion leading, overcoming opposition at Bir Lahfan and reaching the airfield at El-Arish, while to the south ‘Harel’ units reached the village of Kusseima. The Israeli forces poised to hit El-Arish from the south now regrouped to prepare for the next phase. Their purpose was to create a threat at El-Arish and Rafah that, coupled with pressure from the ‘Golani’ Brigade along the Gaza front, would encourage the Egyptians to withdraw their remaining forces from south-west Palestine.

In the meantime, on 29 December, the Security Council of the United Nations ordered another cease-fire. Egyptian appeals to the other Arab

The Conquest of Auja (Nitzana)—Operation 'Horev', 27 December 1948

Contingents to mount diversionary attacks against Israel were in vain, but the Egyptian salvation was to come from a totally unexpected quarter. On 1 January 1949, the United States Ambassador to Israel delivered an ultimatum from the British Government: unless Israeli forces withdrew from the Sinai, the British would be obliged to invoke the provisions of the Anglo-Egyptian treaty of 1936, and to come to the aid of the Egyptians. (Ironically, the Egyptians had been mounting a campaign to abrogate the treaty, a goal that was in fact achieved seven years later by President Nasser.) Unwilling to take unnecessary political risks, and mindful of the inherent weakness of the new State, Ben-Gurion ordered General Allon to

Postpone the attack on El-Arish and to withdraw all forces from the Sinai by the morning of 2 January. But for this ultimatum, the Egyptian forces, which were already beginning to withdraw from the Gaza area in disorder and panic, would have been doomed.

New plans were accordingly drawn up by the Israeli Command to achieve the aims of Operation ‘Horev’ without actually operating on Egyptian territory. Efforts were to be directed at cutting off the Egyptian forces in the area of Rafah, and to capturing the Rafah crossroads. The ‘Golani’ and ‘Harel’ Brigades, supported by a battalion of the ‘Negev’ Brigade, with the 8th Armoured Brigade and the remainder of the ‘Negev’ Brigade held in reserve, were given the mission. The ‘Golani’ force launched its attack on the night of 3/4 January 1949, aiming to capture the cemetery and nearby high ground, as well as Hill 102; it captured the cemetery but failed to take Hill 102. The ‘Harel’ Brigade and units from the ‘Negev’ Brigade, led by the 4th Battalion of ‘Harel’, advanced on Rafah from the south. Their advance reconnaissance and preparation had been inadequate, but they advanced doggedly from position to position, capturing four strongpoints during the night. Additionally, two positions were captured by the 5th Battalion of the Brigade in a fierce bayonet attack. The struggle took place in a violent sandstorm, but the Armoured Brigade that was due to break through into the Rafah camps, thus completing the operation, was once again delayed and did not arrive as planned. Furthermore, because of communication difficulties, it failed to advise the ‘Harel’ forces now holding the crossroads about the delay. Thus, when the ‘Harel’ troops heard the sound of armoured units advancing through the heavy sandstorm they assumed it to indicate the arrival of the 8th Armoured Brigade reinforcements — too late did they realize that it was an Egyptian armoured counterattack. Driven off the position, the Israelis counterattacked but could not make up the lost ground.

‘Golani’ Brigade troops meanwhile extended the area under their control, almost reaching the ‘Harel’ outposts and thus closing off the Rafah camps. The fate of the Egyptian army in the Gaza area now hung in the balance, with the Israeli forces consolidating around Rafah and preparing for the final blow that would cut the Egyptian lines of communication. As the Israelis deployed for the final push, the blinding sandstorm that was raging finally became so bad that operations were impossible. However, the Egyptian Command had already drawn its own conclusions: the bulk of the army was now doomed, and it was but a matter of hours before it would be cut off from its supplies and destroyed by the Israeli forces. Acknowledging the inevitable, the Egyptian Government declared its willingness to enter into negotiations for an armistice agreement.

International pressure in the United Nations and elsewhere was now mounting against Israel, and the British sent a patrol of fighter aircraft to reconnoitre the Sinai and ensure that the Israelis had withdrawn from Egyptian territory. Israeli pilots patrolling the border with Egypt encountered British Spitfires, which (according to the Israeli pilots’

Reports) were strafing Israeli transport inside Israel. A series of dogfights ensued as the Israeli fighter aircraft engaged the British patrol over Israeli air space in the Negev. In all, five British Spitfires were shot down, four in aerial combat and one by ground fire. Two British pilots lost their lives, two were taken prisoner by the Israelis and one succeeded in making his way to the Egyptian lines. (One of the Spitfires was shot down by a young pilot in the first Israeli Fighter Squadron, 101, Ezer Weizman, in later

Years to command the Air Force and become Minister of Defence.) Later that day, an RAF patrol consisting of one Mosquito with an escort of Hawker Tempests came looking for the missing Spitfires. They too were engaged by aircraft of 101 Squadron, and one of the Tempests was shot down. The British reaction was violent and threatening: the Israelis found themselves with no choice but to agree to a cease-fire, which came into force on 7 January.

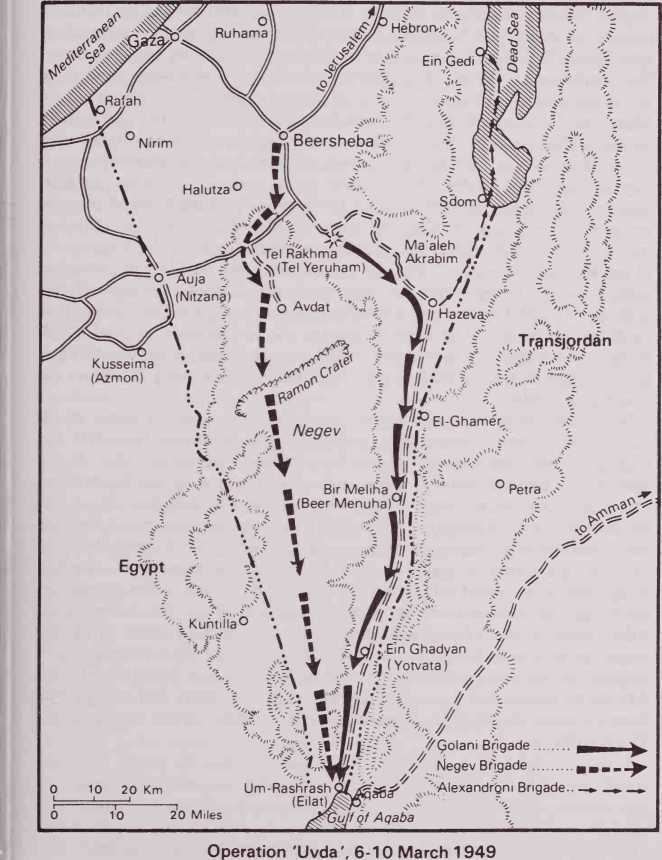

The area of the Negev, with its apex at the northern tip of the Gulf of Aqaba, where the distance between the Egyptian and Jordanian frontiers is some six miles, had been allocated to the State of Israel by the Partition Resolution, but it had not all been brought under actual Israeli control. The Jordanians, with whom preliminary discussions were being conducted at the time, maintained some military control in the southern part of the Negev, and demanded that that area be allocated to Jordan. The Israelis now saw that the most propitious time in which to establish control over the area would be between the signing of the armistice agreement with Egypt and the opening of the armistice negotiations with Jordan. Accordingly, in March 1949, the ‘Negev’ Brigade and the ‘Golani’ Brigade mounted Operation ‘Uvda’. Because of the cease-fire, the strictest instructions were issued to ensure that Jordanian forces in the Negev were in no way to be engaged and no hostile activities were to be mounted against them. The operation was thus envisaged as a series of manoeuvres that would outflank the small Jordanian patrols in the area and make their positions untenable. The main force, the ‘Negev’ Brigade, moved south through the wadis and mountains of the central Negev, while the ‘Golani’ Brigade moved southwards along the Wadi Arava route parallel to the Jordanian border.

Some Jordanian patrols opened fire, but the Israeli forces, which outnumbered them considerably and had set up a makeshift airfield for supplies in the centre of the Negev Desert, easily bypassed them. By 10 March, the small Jordanian outposts had withdrawn across the border, and Um-Rashrash, a desert outpost situated on the Red Sea coast, was evacuated. Two hours later, the Israeli forces arrived there and Captain Avraham (‘Bren’) Adan, a battalion commander in the ‘Negev’ Brigade, shinned up a makeshift pole and affixed to it an improvised flag — a white sheet with the Shield of David drawn on it in ink — marking the assumption of Israeli authority in what was later to be the port of Eilat. Adan, a small, wiry, fair-haired man, hailing from the kibbutz of Nirim, where he had first fought against the invading Egyptian forces, and a veteran of the wars of the Negev, was later to command the Israeli Armoured Corps and subsequently one of the divisions that crossed the Suez Canal in the 1973 War leading to the encirclement of the Egyptian Third Army.

World History

World History