Pare for war, and Neurath, whom IlindcMi-burg had made foreign minister to safeguard the foreign serviee against Nazi influence, was replaced by Rihhentrop who for years had been pushing a radical Nazi policy in open rivalry with the more cautious official line of the foreign office.

The annexation of Austria which followed (March 1938) was an improvisation, hut an improvisation which fitted in perfectly with Hitler’s long-term programme and illustrates the relationship between this and the tactics of opportunism. Throughout the rest of 1938 and 1939, it was Hitler who forced the pace in foreign affairs, both externally by the demands he made on Czechoslovakia and Poland and internally by his determination to take risks which still, in 1938, alarmed the army leaders and led to the resignation of the army’s chief-of-staff. General Beck. Neither in 1938 nor in 1939 did Hitler deliberately plan to start a general European war; in August 1939 he was convinced that the masterpiece of Nazi diplomacy, the Nazi-Soviet Pact, would remove any danger of Western intervention and either break the Poles’ determination to resist or leave them isolated. But when his bluff failed, he steeled himself to gamble on the chances of a Blitzkrieg victory over Poland before the British and French could bring their forces to bear. The gamble came off and came off again, with the stakes increased, in Norway, the Low Countries, and France in 1940, against Yugoslavia, and almost against Russia the next year. By then the stakes had been raised to the point where failure meant the long-term, two-front war which Hitler had sworn to avoid, and for which Germany was ill-prepared.

The particular war which broke out in September 1939 was not inevitable —what event in history is? But it was no accident either. Nazism glorified force and conflict, and if one thing seemed certain in the later 1930’s it was that this movement which had fastened its hold on Germany must, from the necessities of its own nature, seek to expand by force or the threat of force. Once Nazism —a philosophy of dynamism or nothing —came to a standstill and admitted limits to its expansion, it would lose its rationale and its appeal. The only question was whether the other powers would allow this expansion to take place without resistance or would oppose it. The Nazis themselves had always assumed that at some point they would meet opposition and had prepared to overcome it by force of arms. For this reason, while it is right to point to the differences between Nazi Germany up to September 1939 and after the outbreak of war, it is important to see the continuity between the two periods as well. What followed was a logical, if not inevitable, consequence of what went before.

The Brink of War

The international conference at Munich on 29th September 1938 had a practical task: to 'solve’ the problem of the three million German-speakers in Czechoslovakia and so to prevent a European war. Apparently it succeeded in this task. The Czechoslovak territory inhabited by the three million Germans was transferred to Germany; the Germans were satisfied; there was no war. The controversy which has raged over the conference from before it met until the present day sprang more from what it symbolized than from what it actually did. Those who welcomed the Munich conference and its outcome represented it as a victory for reason and conciliation in international affairs —appeasement as it was called at the time, 'jaw, not war’, as Winston Churchill said of a later occasion. The opponents of Munich saw in it an abdication by the two democratic powers, France and - Great Britain; a surrender to fear; or a sinister conspiracy to prepare for a Nazi war of conquest against Soviet Russia. Munich was all these things.

The problem of the German-speakers in Czechoslovakia was real. They had been a privileged people in the old Habsburg monarchy. They were a tolerated minority in Czechoslovakia. They were discontented and grew more so with the resurgence of national pride in Germany. No doubt Hitler encouraged their discontent, but he did not create it. Those in the West who called out, 'Stand by the Czechs’, never explained what they would do with the Czechoslovak Germans. Partition seemed the obvious solution. In fact, as later events proved, Bohemia was the one area in Europe where partition would not work. Czechs and Germans were so intermingled that one or other had to dominate. Once Czech prestige was shattered, a German protectorate inevitably followed six months later, to the ruin of the Munich settlement. The Czechs themselves recognized that there was no room in Bohemia for both nationalities. When independent Czechoslovakia was restored at the end of the war, the Germans were expelled —a solution which is likely to prove final.

The timing of the Czech crisis was not determined by the Czechoslovak Germans

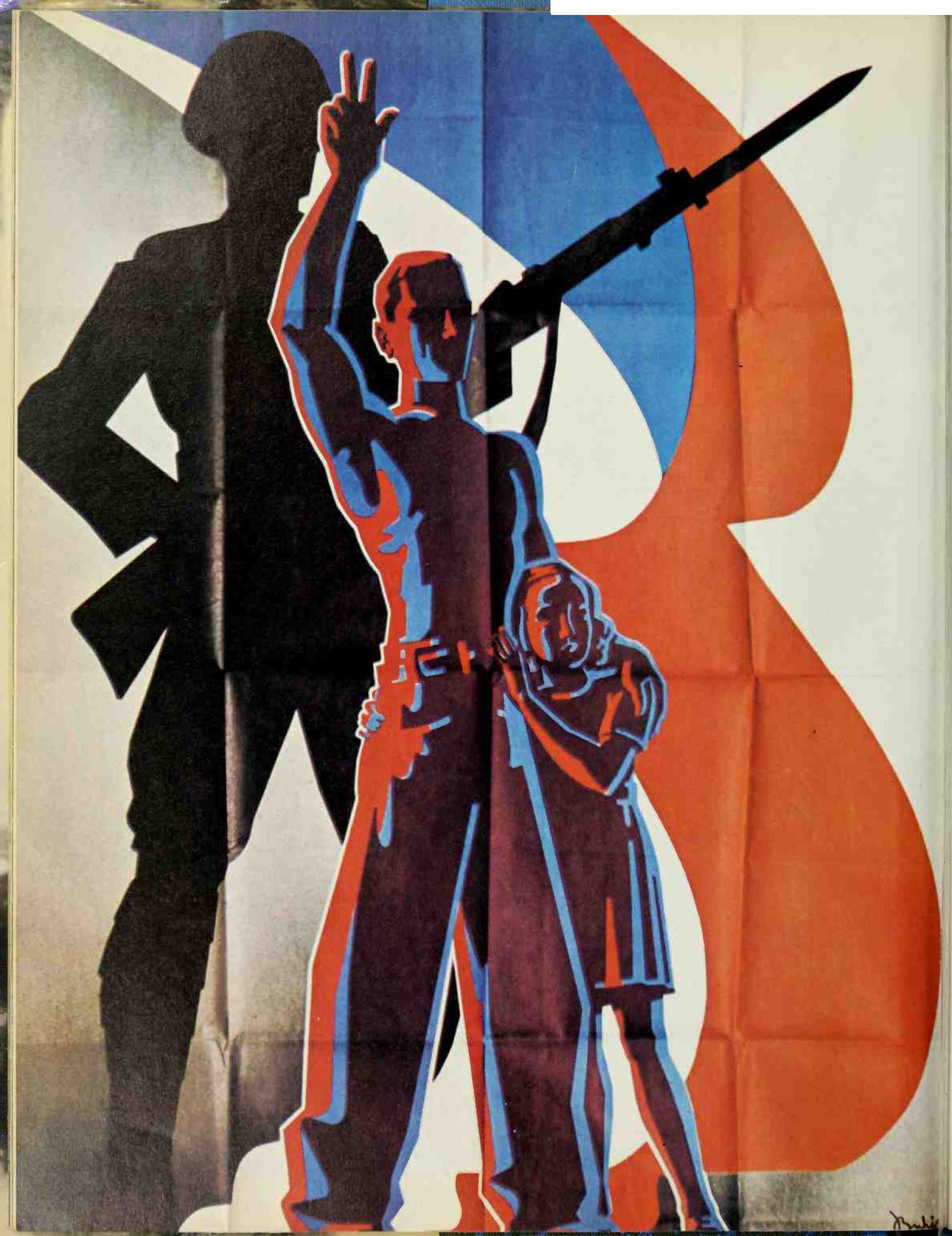

Left: A poster distributed throughout Czechoslovakia in 1938: 'We will all become soldiers if necessary. ’

Czech morale remained high during the war of nerves conducted by Hitler.

Right: Britain’s Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain arriving at Heston Airport, London, promising 'Peace in our time’

Or by Hitler. It was determined by the British government, and especially by Neville Chamberlain, the British Prime Minister. He wanted to restore tranquillity in Europe and believed that this could be done only if German grievances were met. Moreover they must be met willingly. Concessions must be offered to Germany, not extracted under threat of war. Until 1938 Hitler had been destroying one bit of the 1919 settlement after another, to the accompaniment of protests from the Western powers. This time Chamberlain meant to get in ahead of him. Hitler was to be satisfied almost before he had time to formulate grievances.

Fear not reason

Chamberlain set himself two tasks. First, the French must be induced not to support their ally, Czechoslovakia. Second, the Czech government must be persuaded or compelled to yield to the German demands. He succeeded in both tasks, but not in the way that he intended. He had meant to use the argument of morality: that German grievances were justified and therefore must be redressed. Instead, as the months passed, he came to rely on practical arguments of force and fear. The French were driven to admit, with a reluctance which grew ever weaker, that they were unable to support Czechoslovakia. The Czechs were threatened with the horrors of war unless they gave way. When Chamberlain flew to Munich on his first visit to Hitler, it was not as the emissary of even-handed justice. He came in a desperate effort to avert a war which the Western powers dreaded. Thereafter fear, not reason, was his main argument, and the principal moral which the British drew from Munich was not that conciliation had triumphed, but that they must push on faster with rearmament.

At the Munich conference there was certainly an abdication by the Western powers. France especially had been the dominant power in Eastern Europe since the end of the First World War. Germany was disarmed; Soviet Russia was boycotted; all the new states of Eastern Europe were France’s allies. She regarded these alliances as a source of strength. As soon as her allies made demands on her, she turned against them. France had been bled white in the first war, and Frenchmen were determined not to repeat the experience. They believed that they were secure behind their fortified frontier, the Maginot Line. Hence they did not care what happened beyond it. As to the British, they

World History

World History