In Spring 1981 the ongoing civil war in Lebanon, which had been ravaging that unhappy country since 1975, took a new turn as the Syrian forces manning the Damascus-Beirut road pushed northwards in order to penetrate the mountainous area north of the road and northeast of Beirut held by the Christian Phalangist forces commanded by the Christian leader Bashir Gemayel. These forces had since 1976 been receiving military supplies from Israel, and had been urging the Israelis to become militarily involved in Lebanon in order to evict the Syrian forces and the PLO.

This renewed outburst of fighting in Lebanon erupted around the Christian town of Zahle in the Beqa’a Valley and on the main highway linking Beirut with Damascus. The citizens of Zahle had attempted to construct an alternative road to this highway, which was controlled by the Syrians, and which would enable them to be in direct contact with the mountainous area further east controlled by the Christian Phalangist forces. The Syrians were opposed to the construction of such a road and began a systematic shelling of the town of Zahle. Fighting erupted between the Syrian Army and reinforced Christian units as the Syrians began to destroy the town indiscriminately. Heavy casualties and loss of materiel resulted from the fight around Zahle, which was placed under siege by the Syrians.

Late in April 1981 the Syrians attacked the Christian position on Mount Sanine known as the ‘French Room! This strategic position affords artillery control of both Zahle and the port of Jounieh, which had become the capital city of the Christian Phalangist enclave to the north of Beirut. Through this port the Christians received all their supplies.

When the Syrians encountered heavy resistance on the ‘French Room’ and on Mount Lebanon, they launched attacks by assault helicopters on 25-27 April, 1981. Their very effective use of helicopter missile fire directed point-blank at the Christian mountain positions placed the Christians in a very serious predicament, and in danger of being overrun by the Syrian Army.

The Phalangists appealed in desperation to Israel for help, maintaining that the Lebanese Christian community without protection from air attack faced slaughter and possible annihilation. Prime Minister Begin ordered the Israeli Air Force to lend support to the Christians, maintaining that the Christian community faced the danger of a holocaust.

As the Israelis saw it, for the first time in four years of Syrian intervention in Lebanon, the threat of annihilation of the Christians meant that the tacit ‘red line’ with Israel had been crossed.

In pursuance of Mr. Begin’s decision, on 28 April the Israel Air Force shot down two Russian-built MI-8 Syrian helicopters engaged in supplying the attacking Syrian forces. This action too broke one of the unwritten, tacit agreements which characterized the Israeli-Syrian relations in Lebanon. Thereupon the Syrians, in order to protect their forces against the Israel Air Force, moved their surface-to-air missiles—which covered from Syrian territory the Beqa’a Valley in east Lebanon held by the Syrians—into the Beqa’a Valley, thus violating another unwritten Syrian-Israeli agreement. For the presence of the Syrian surface-to-air missile batteries in the Beqa’a Valley hampered the regular Israeli reconnaissance flights taking place over Lebanese territory, in which hitherto the Syrians had tacitly acquiesced.

The Israelis requested through Ambassador Philip Habib, the U. S. mediator who had been sent to the area by President Reagan, that the Syrians withdraw their missile sites from inside Lebanese territory. The Syrians refused. According to Mr. Begin at a political rally (Israel was in the throes of a campaign in national elections which were to be held on 30 June), Israeli aircraft had been sent to attack these missile sites in April, but had failed to do so because of heavy clouds in the area. Ambassador Habib continued his efforts, with little success.

Mr. Begin’s Likud party won a slight majority over the Labour Alignment, which made a spectacular come-back, gaining 47 seats in place of the previous 32. Mr. Begin was able, with the aid of the three religious parties in the Knesset, to form a coalition government.

In July 1981 PLO units in southern Lebanon opened hea'vy and indiscriminate fire from long-range 130 mm Soviet-type guns and Katyusha rocket launchers against some 33 Israeli towns and villages in northern Galilee. The battle on the northern border of Israel was waged for some ten days, with the Israeli population driven into shelters.

It became clear that Israel could not afford to live with such a situation, which had brought to a halt normal life in northern Galilee. In Kiryat Shmoneh, industry came to a standstill with a high proportion of the population leaving the town. In the northern resort town of Nahariya the tourist industry came to a halt.

The Israeli reaction, which included the bombing of PLO headquarters and stores in Beirut and PLO bases throughout Lebanon, was wide-ranging, fierce and massive. At this point. Ambassador Philip Habib instituted negotiations in order to achieve a cease-fire, to which both sides—the Israelis for whom life in the Upper Galilee was being disrupted, and the PLO who were suffering heavily from Israeli counter-action—were receptive. On 24 July 1981, using Saudi Arabian mediation with the PLO, Ambassador Habib arranged a cease-fire. Life in the Galilee began to return to normal.

Soon, however, differences of opinion emerged as to the nature of the cease-fire. The Israelis maintained that they understood the cease-fire to be a complete cease-fire in which no action would be taken against Israeli targets in Israel or Israeli and Jewish targets abroad. The PLO maintained that the agreement covered only operations across the Lebanese-Israeli border. The American interpretation tended in favour of accepting the cease-fire as applying to targets in Israel from whatever direction the attack came, but not to targets abroad. Soon, while the northern border remained peaceful, other PLO-mounted operations took place. There were clashes and encounters with PLO units which crossed the border into Israel from Jordan across the Jordan River; terrorist activities took place within Israel; an Israeli diplomat was assassinated in Paris; Israeli and Jewish targets were attacked in various parts of Europe. Israel made it clear that all these activities were a violation of the cease-fire. Over 240 terrorist actions were mounted by the PLO against Israeli targets during the cease-fire.

On a number of occasions tension rose to almost breaking-point as Israeli forces were mobilised and poised to cross the Lebanese border. The Israeli Defence Minister, Mr. Ariel Sharon, made it clear that Israel’s intention was to cross the border in force and wipe out the PLO infrastructure. In his various discussions, including those with representatives of the American Government, he stated his desire to link up with the Christians north of Beirut and by so doing, to influence the creation of a stable government in Lebanon, thereby ridding the Lebanon of PLO and Syrian forces, and conceivably achieving normal relations with Israel.

A major consideration at the time was that Israel was due to withdraw finally from Sinai on 26 April in accordance with the Israel-Egypt peace treaty, and it was felt that neither Egypt nor the U. S. would react adversely to Israel’s intention to cross the border lest such opposition would give Israel second thoughts about withdrawing from Sinai. However, powerful U. S. pressure and opposition within the Cabinet led to the postponement of this operation.

The Israeli withdrawal from Sinai was completed against heavy internal opposition, forcing the Israeli armed forces to evict many who refused to vacate Israeli settlements in Sinai and the town of Yamit. Thereafter the process of normalisation between Israel and Egypt proceeded apace.

There were increasing signs of unrest within the PLO camp because a cease-fire with Israel in effect removed much of the raison d’etre of that organization. Pressures were growing to resume hostile activities against Israel.

On Thursday, 3 June, the Israeli Ambassador to the Court of St. James’s, Mr. Shlomo Argov, was leaving a dinner party at the Dorchester Hotel in London when a would-be assassin fired at him, causing him critical injuries in the head. The assailant was shot down by a special Scotland Yard security officer and his accomplices were apprehended a short while thereafter by the London police, who uncovered a terrorist gang with quantities of arms and lists of prominent Israelis and Jews in Britain marked for assassination. The three men apprehended included an Iranian, a Jordanian and an Iraqi. They apparently belonged to an Iraqi terrorist group which had broken away from the PLO when led by one Abu Nidal, and had been adopted by the Syrians. The PLO denied complicity in the assassination attempt.

The Israeli Cabinet met and decided that it could no longer remain silent in face of such provocation, and on Friday, 4 June, heavy Israeli air attacks

Were launched against PLO targets in the area of Beirut and throughout the Lebanon. The PLO reacted immediately with artillery and Katyusha fire on the Israeli settlements in northern Galilee, causing considerable damage and some loss of life.

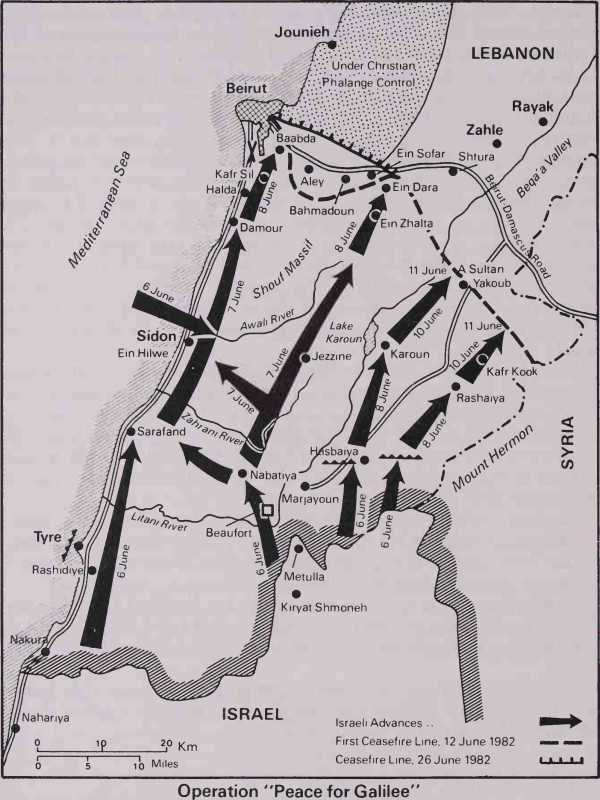

On 6 June at 11.00 hours, a large Israeli armoured force crossed the Lebanese border in Operation ‘Peace for Galilee.’ The Government of Israel declared that the purpose of this operation was to ensure that the area north of the Lebanese border would be demilitarised from all hostile elements for a distance which would place the Israeli towns and villages along the border out of range. As the Government spokesman announced, the purpose of the operation was to put “...all settlements in Galilee out of range of terrorist artillery...positioned in Lebanon.” In other words, this would mean an operation encompassing an area to a distance of some 40 kms. (25 miles) north of the Israeli border.

The main features of Lebanon are two alpine mountain ranges (the Lebanon, reaching a height of 2,046 metres, south of Beirut, and the Anti-Lebanon, reaching a height of 2,814 metres at Mount Hermon). These ranges divide the country into four parallel zones running from north to south. These are: the coastal plain; the Lebanon ridge; the Beqa’a Valley; and the Anti-Lebanon ridge, the crests of which mark the border between Lebanon and Syria.

The mountainous area is particularly difficult for armoured fighting vehicles: the mountain roads are narrow, poorly maintained and easily defended. The coastal area varies between a width ranging from a few hundred metres to a few kilometres, with towns and villages such as Tyre, Sidon and Damour constituting effective road-blocks along the route.

The Beqa’a Valley can be easily covered by fire from the surrounding mountain slopes and the extensive agriculture in the area makes it easy for defending forces to conceal themselves. The Litani River crosses a good part of Lebanon from east to west from the area of the Beqa’a Valley to the Mediterranean, and the southern Beqa’a and its approaches from Israel are dominated by the Beaufort Heights rising to a height of 717 metres near the bend of the Litani River. Manning this highly defensible area were two military forces—the PLO forces and the Syrian Army. The PLO controlled some 15,0(X) fighters organized in military formations, under the overall command of its Supreme Military Council. This force was deployed along the western slopes of the Hermon range, known generally as ‘Fatahland’; in the Nabatiya area comprising the Amoun Heights and commanding the bend of the Litani River; and along the main axis between the southern tip of the Beqa’a Valley and the Mediterranean shore south of Sidon. The Nabatiya area also controls the so-called central axis to the north from Israel, the Aichiye-Rihane area, the Tyre region, the area south and east of Tyre based on Jouaiya, the Greater Sidon area and the north coast region between Damour and Beirut. In each of these areas the PLO forces ranged in size between approximately 1,500 fighters and brigade strength, armed with a wide assortment of light and heavy weapons, artillery ranging up to calibres of 130 mm and 155 mm and Katyusha rocket launchers including some capable of firing forty 122 mm rockets. Over 100 obsolescent

Russian-type T-34 tanks and a number of UR-416 personnel carriers completed the PLO armoury, which included a very large variety of antitank and anti-aircraft weapons.

The PLO had, in fact, taken over a considerable part of the area of southern Lebanon and had created within it a ‘state within a state.’ Lebanese authority was superseded by the brutal PLO terrorist methods which created a nightmare for the Lebanese inhabitants. Much of their military infrastructure was located in the midst of urban and rural areas; thus the cellars of large apartment houses were converted into storage areas for weapons and high-explosive amnumition, and apartments in many buildings were turned into weapon placements. The deployment of PLO forces was planned in such a way as to turn the civilian population into a live shield, and in fact into hostages in the hands of the PLO.

Since 1976 the Syrian Army, which had intervened and had entered Lebanon at the request of the Christian forces to protect them from the attacks of the PLO, had established itself with a force of approximately

30,000 troops in Lebanon. Ostensibly, this was part of an Arab peacekeeping force designed to impose a cease-fire in the Lebanese civil war, but gradually the other Arab contingents withdrew when it began to become clear that the Syrian ‘peace-keeping force’ was in effect a Syrian occupation force designed to implement Syria’s policy of turning Lebanon into a vassal state.*

The Syrian forces in Lebanon included a division-size force including a tank brigade and two infantry brigades of the so-called Palestinian Liberation Army (PLA). A further tank brigade and support troops were deployed in the area between the Syrian border and Joub Jannine, covering batteries of SAM-2, SAM-3 and SAM-6 surface-to-air missiles positioned in Lebanon. Further south a brigade-size force was deployed in the Beqa’a Valley on both sides of Lake Karoun down to the area of Hasbaiya. The Syrian force in Lebanon included some 200 tanks with an additional 100 tanks on the Lebanese border. In most of the areas controlled by the Syrians, particularly in the south-eastern sector, PLO forces positioned themselves behind the cover of the forward Syrian troops.

The Israelis concentrated a large armoured force in order to move into Lebanon. The figures published indicate a force of eight divisional groups. The Israeli plan was for a three-pronged push: one along the coastal plain which would bring the Israeli forces to the area north of Damour or the southern suburbs of Beirut and the international airport; a central force which would advance through the Shouf Massif, and would cut the Beirut-Damascus road in the area of Ein Dara to the west of Shtura; and an eastern force which would roll up ‘Fatahland’ to the southern part of the Beqa’a Valley.

The purpose of the three-pronged attack was to destroy the PLO military infrastructure, and clear the area north of Israel for a distance of 40-45 kms. (25 miles). The strategic purpose of the central advance was to reach the ¦"Syria never recognised Lebanon as an independent country, and in fact had no formal diplomatic relations with Lebanon. There was never any Syrian embassy in Beirut. It maintains that Lebanon is part of Greater Syria.

Damascus-Beinit road, turn eastwards along that road, and by feinting in the direction of the Syrian border to cause the Syrian forces in the Beqa’a Valley, who would thus be in danger of being outflanked, to withdraw eastwards towards the Syrian border.

The assumption was that the main strategic key to the operation must be establishing a presence on the Beirut-Damascus road. This was Syria’s first strategic aim when its forces entered Lebanon in 1976. The isolation of Beirut from Damascus was considered to be essential.

The operation was commanded by Major-General Amir Drori, GOC Northern Command. A product of Israel’s Military Academy, he had advanced in rank in combat units. In the 1973 Yom Kippur War he commanded the Golani Infantry Brigade, including in the heavily fought battle for the recapture of Mount Hermon. He himself was severely wounded. He rose to command a division, to head the Training Branch at GHQ, and finally to be GOC Northern Command. A quiet, soft-spoken, intellectual man, he was rather typical of the new professional officer who had grown up in the Israel Defense Forces.

The forces operating in the eastern sectors were commanded by Major-General Avigdor Ben-Gal (‘Yanosh’), who a year earlier had left his post as GOC Northern Command for a year of academic studies in the United States. He returned in the midst of his studies to assume a field command. Once again, he was to find himself in military confrontation with the Syrian armoured forces.

Shortly after the central thrust, two columns to the west crossed the border—one column advancing along the coastal road towards Tyre with a parallel column moving along an internal road towards the foothills overlooking the coast and parallel to the coastal operation.

The coastal column was led by an armoured brigade commanded by Colonel Eli Geva, who had been a company commander in the tank force that fought so desperately against the Syrian invasion of the Golan Heights in 1973.

The policy laid down was for the forces to advance and reach the final objectives as rapidly as possible, thus closing off the escape and reinforcement routes of the PLO, and only thereafter to mount a mopping-up operation and engage the PLO forces.

Thus the forces advancing along the coastal road by-passed a heavy concentration of PLO units and moved forward rapidly in order to join up with the task force which was to be landed by the navy from the sea. By midnight, 6-7 June, the advance units had reached the town of Sarafand. As the coastal column advanced, a landing was effected near the mouth of the Litani River at Qasmiya, and the town of Tyre was closed off.

To the east of this force the Syrian task force moved along the slopes of the Hermon towards Rashaiya El-Foukhar while another force advanced from Metulla on Hasbaiya. Yet another force moved in a north-easterly direction, by-passing the Beaufort positions and moving towards the strongly held area of Nabatiya.

On the second day of the fighting, the advancing forces along the coastal road reinforced by the eastern arm of the coastal attack, which had crossed the Aqiya Bridge across the Litani River and had been advancing in the foothills above the coastal road, linked up with the task force which had been landed from the sea to the north of Sidon.

Meanwhile, Tyre was completely isolated, and its inhabitants were advised to leave the town and to concentrate along the seashore in order to enable the Israeli forces to proceed with the task of evicting the PLO terrorists who had taken up positions in the buildings throughout the town. This move undoubtedly saved a large number of civilian lives, because the fighting against the PLO in the town was to prove to be fierce and bitter.

In the central sector, shortly after midnight on 7 June, the well-nigh inaccessible Beaufort Crusader fortress was captured after heavy fighting and serious casualties by the Golani Brigade reconnaissance unit. From this fortress the PLO had dominated northern Galilee and were able to direct their artillery fire against targets in northern Galilee and in the southern part of Lebanon held by forces comanded by Major Saad Haddad, a Lebanese officer who had created an enclave of approximately 100,000 Christians and Shi‘ite Moslems which was linked to, and supported by, Israel.

Meanwhile, in the central sector the troops of the central task force stormed the Arnoun Heights and established themselves in the Nabatiya sector. The Hardale Bridge across the Litani River was taken and in the central sector the forces commenced to advance, against strong resistance, along the narrow mountain roads. The Israeli forces came up against the first strong concentration of Syrian forces in the area of the town of Jezzine. The task force to the east advanced slowly along narrow roads and gorges which were easily defensible, past Hasbaiya. The Syrians moved the 91st Armoured Brigade to the southern Beqa’a Valley.

The problem facing the Israeli command now in the central and eastern sectors was that the Syrians were blocking any possibility of achieving the 40 kilometre limit from the border of eastern Galilee. The Government of Israel announced officially that it would not engage the Syrian Army unless its forces were engaged by the Syrian Army. Messages were passed via Washington, suggesting that the Syrians take control of the PLO and prevent them shelling targets in Israel. The problem for Israel was complicated by the fact that the PLO units in the eastern sector had withdrawn behind the covering screen of the Syrian forces, and indeed for the first two days fired sporadically into the eastern panhandle of the Galilee.

When the Israeli proposal evoked no response on the part of the Syrians, whose reaction was to strengthen considerably their forces in the eastern sector, the sporadic firing which had taken place along the Israeli-Syrian front line now developed into full-scale fighting. In the general area to the south of Lake Karoun, the Israeli forces were facing a Syrian commando battalion in addition to an armoured battalion from the 62nd Syrian Brigade, which was deployed along the Damascus-Beirut road. Additional Syrian reinforcements in the form of the 51st Brigade were moved southwards from the Shtura area to the area south of Jezzine.

On the third day of the fighting, the parallel forces which had joined together on the coast road now advanced towards Damour. Operations against the PLO units in Tyre and Sidon were escalated; the Israeli forces faced the problem of endeavouring to avoid civilian casualties while at the same time the PLO held large groups of civilians as hostages in order to prevent Israeli attacks. In many cases the Israelis endangered the lives of their own troops in order to avoid causing heavy casualties to the civilians, but the severe fighting inevitably took its toll of civilians too.

In the central sector, the armoured battle developed in the Jezzine area with an Israeli task force ranged against a Syrian armoured brigade strengthened by an infantry battalion and a commando battalion. The Syrian 1st Armoured Division assumed responsibility south of the area of Lake Karoun. After a day’s battle the Syrian forces withdrew from the Jezzine Heights, and the central task force advanced some 20 kms., thus threatening the whole area to the east of Lake Karoun and the roads leading down to the Mediterranean. The outskirts of Beit El-Din and Ein Dara were reached. This advance was beginning to threaten the Syrian hold over Beirut.

Heavy fighting continued in the eastern sector, with the Syrians making full use of their commandos manning anti-tank missile units, which were effective in the narrow passes and tortuously narrow roads in the mountainous area. The roads were mined, the passes were blown up, and the advance, because of the nature of the territory, was very slow. The Israeli Air Force became a central factor in this fighting. Meanwhile the Syrian Air Force began to intervene in the fighting, and in three separate dogfights six Syrian MiG planes were shot down: there were no Israeli losses.

Probably one of the most significant events of the war, within the purely military connotation, occurred on 9 June, the fourth day of the fighting. Once the Israelis had decided to push the Syrian forces in Lebanon back to the 40 kilometre limit from the Israeli border, it was clear that air support in such an operation was essential if casualties were to be kept to a minimum. The terrain was mountainous, with narrow roads, deep gorges, heavily wooded and easily defensible, and was much more suited to defense than to an armoured attack. But the air space over the battlefield was covered by the surface-to-air missile batteries which the Syrians had brought into the Beqa’a Valley a year earlier and had now reinforced. These batteries, of the SAM-2, SAM-3 and SAM-6 types, hampered the operations of the Israeli Air Force over the battlefield. Accordingly, the Israeli Government decided on an attack against these surface-to-air missiles. At 14.00 hours the Israeli Air Force attacked, with the result that 19 batteries were completely annihilated and four were severely damaged, without the loss of a single Israeli plane.

The Syrian Air Force reacted in strength to this Israeli operation, and one of the major dogfights to have taken place in the history of air warfare developed over the Beqa’a Valley. According to the Syrians, some 100 Israeli planes participated in the operation and 100 Syrian planes were ranged against them. In the battle which followed, 29 Syrian planes were shot down, without any Israeli losses. In the ensuing days the Syrians renewed their air attacks as the Israeli Air Force intervened to prevent the entry of additional surface-to-air batteries into Lebanon.

In all, in the course of the first week’s fighting in the war, a total of 86 Syrian planes, all first line, of the MiG-21, MiG-23 and Sukhoi-22 types, were shot down without the loss of one Israeli plane. The only Israeli air losses had been two helicopters and a Skyhawk plane which had been shot down by PLO missile fire.

The Israeli victory over the missiles gave Israel complete mastery of the air. There had been much conjecture as to whether or not the Syrians would attack the Golan Heights in the event of a Syrian-Israeli clash in Lebanon. The destruction by Israel of the missile system in Lebanon and of some 15% of the first-line planes of the Syrian Air Force doubtless affected the Syrian considerations in this respect. The air victory was a dramatic one which gave rise to considerable concern in the Warsaw Pact headquarters, and to considerable interest in the Western countries, particularly NATO. This new development now enabled the Israeli forces to take full advantage of Israeli air power and to dominate the battlefield.

Meanwhile, on the western sector the Israeli forces tightened their grip on the PLO in Sidon, and on the Ein Hilwe refugee camp from which area the PLO forces were resisting. Once again an attempt was made to divide the civilian population from the combatants by calling on the civilians to congregate on the seashore and thus avoid unnecessary civilian bloodshed.

The armoured and infantry forces now advanced to the township of Damour, some 18 kms. (11 miles) south of Beirut. Damour, which had been a beautiful Christian township, had been destroyed by the PLO in 1976, when they massacred a considerable part of the Christian population and drove the rest out. The town was occupied by PLO camps and headquarters, with ammunition dumps and weapons storage warehouses located everywhere. Heavy fighting took place in this town, which fell after a bitter battle.

Meanwhile, in the central sector, heavy tank battles with the Syrians were taking place around Ein Dara, which commands the Damascus-Beirut highway from a distance of 3 kms. Here the Syrians, using heavy concentrations of anti-tank weapons manned by special commando units, fought stubbornly in order to prevent Israeli forces from reaching the stragetic road.

In the eastern sector, the easterly effort of Ben-Gal’s corps finally broke through the Syrian defenses and advanced in the area east of Lake Karoun, joined in battle as it was with the 1st Syrian Armoured Division, which fought stubbornly and contested every position. Ben-Gal sent part of his force around the western shores of Lake Karoun. This force was able to attack the right-hand rear flank of the Syrian 1 st Armoured Division which was resisting the Israeli advance up the Beqa’a Valley to the east of Lake Karoun.

The manoeuvre was effective, and in the battle that ensued the Syrian armoured division suffered considerable losses. One Syrian armoured brigade was totally destroyed, and in all the Syrians lost in this battle some 150 tanks. At one stage in this fighting, an Israeli armoured battalion discovered that it had moved into a Syrian-defended locality in the Beqa’a Valley and was being engaged on all sides, especially from the high ground on both flanks of the valley. Its situation appeared to be desperate, but it was finally relieved by a heavy concentration of artillery fire backed by air support, after having suffered considerable losses.

The advance in the western sector was held up near Kafr Sil, where the Syrians and the PLO had planned an armoured ambush with commando units and special anti-tank forces. The advancing force pinned down the Syrian and PLO forces facing it from the north, and developed an outflanking thrust to the east aimed at cutting off Beirut and the terrorist forces in its western and southern outskirts from the east and the Damascus road.

Meanwhile, as the battle in the central and eastern sectors had developed, Syrian reinforcements were moved into Lebanon; a Syrian armoured brigade en route to the front was completely destroyed by an Israeli Air Force interdiction action, while the Syrian 3rd Armoured Division, which was equipped with the T-72 tank—the most modem in the Soviet arsenal—moved into the Beqa’a Valley. Syrian tank strength in the Lebanon was thus in the region of 700.

The battle on the eastern front sector continued on Friday, 11 June, with the Israeli forces deploying the new Israeli main battle tank, the Merkava (Chariot), fighting the most modern Soviet tank, the T-72. As the 91st and 76th Syrian tank brigades of the 1st Armoured Division fought in the area of Lake Karoun, elements of the 3rd Armoured Division engaged Israeli forces in the Beqa’a Valley. In the course of the fighting, nine T-72 tanks were destroyed by Israeli fire.

Israel announced a unilateral cease-fire, to come into effect at midday on Friday, 11 June. Immediately after the Israeli announcement, Syria announced that it woulcPbbserve the cease-fire too. Israel made it clear that the cease-fire did not apply to the PLO forces. At the outset of the ceasefire, the Israeli forces in the eastern sector were established on the Beqa’a Joub Jannine line with the easternmost elements being some 5 kms. from the Syrian border to the east. Israeli forces in the central sector held the line in the area of Ein Dara, just south, but in range of, the Beirut-Damascus road.

In the western sector, in the area of Kafr Sil held by the Syrian 85th Brigade—by now completely cut off in Beirut—the cease-fire broke down after two hours. The Syrians blocked the road which would enable the Israeli forces to link up with East Beimt via Halde and Baabde. As evening fell, the Israeli forces outflanked the Syrian positions.

Fighting continued in the area of the Ein Hilwe refugee camp near Sidon, with the Israelis calling on the PLO to lay down their arms. They refused, and the fighting continued. Meanwhile hundreds of PLO fighters were giving themselves up or being captured in the area occupied by the Israeli forces.

The fighting continued into 12 June to the south of Beirut, with an Israeli armoured force breaking through after capturing Kafr Sil and moving in the direction of Halde and Baabde, the seat of the President of Lebanon.

BEIRUT

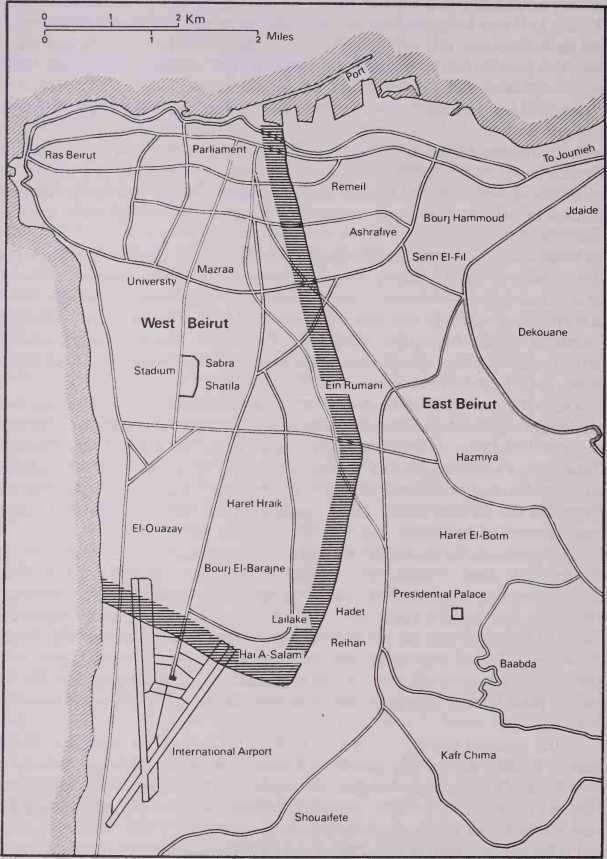

A second cease-fire was negotiated by the American Ambassador, Philip Habib, after the Israeli forces had completely surrounded West Beirut and linked up with the Christian Phalangist forces in East Beirut.

Only on Monday, 14 June, was the Ein Hilwe camp, in which the PLO forces fought stubbornly, taken.

The uneasy cease-fire continued, with frequent eruptions as each side tried to improve its position. On Tuesday, 22 June, Israeli forces attacked the Syrian and PLO positions on the Beirut-Damascus road in the area of Aley-Bahmadoun. This move was designed to push eastwards the Syrian forces which endangered the flanks of the Israeli forces laying siege to Beirut. Once again, the Israeli Air Force was brought into action. The Syrians sent in reinforcements along the Beirut-Damascus road, and Syrian commando forces engaged the Israeli forces from the area of A1 Mansouriya which they had taken the day before. After 60 hours of heavy fighting against the determined Syrian forces, the Israel Defence Forces succeeded in removing the Syrians from the area of Bahmadoun-Aley on the Damascus road. Both sides suffered heavy losses, with the Israelis admitting to 28 killed and 168 wounded in that sector in three days’ fighting. The Syrian forces withdrew eastwards from Bahmadoun. A renewed cease-fire took effect.

An uneasy cease-fire continued, with the Israel Defence Forces tightening their hold around Beirut, from the international airport to the south to the Beirut port to the north. As of mid-July, negotiations were afoot between U. S. Ambassador Philip Habib on the one hand, and through the mediation of the Lebanese Government with the PLO on the other hand, in order to bring about the total evacuation of some 8,000 PLO fighters besieged in Beirut and the remnants of the Syrian 85th Brigade.

On 14 July, the Lebanese Government officially issued a call for the removal of all foreign forces. This was the first time that the Lebanese Government came out in favour of the policy supported both by Israel and the United States. The Israelis announced that while they would retain the military option to move into West Beirut, they would accede to the various requests to give more time for the process of negotiation to take its course.

In the course of the negotiations between Ambassador Philip Habib and the PLO, the cease-fire broke down on numerous occasions.

In Israel, voices were raised against any move by Israeli forces into West Beirut. It was clear that such an operation could be costly, not only to the Israel Defence Forces but also in terms of civilian casualties in the city. From time to time the Israelis applied heavy pressure on the western part of the city by cutting off at intervals the electricity and water supplies. These steps were also the subject of a bitter internal debate in Israel. It was evident that one of the considerations of Yasser Arafat, in prolonging the negotiations on the evacuation of the PLO from Beirut, was that he was not unmindful of the internal debate that was raging in Israel. However, as the Israel Defence Forces intensified their pressure on the besieged city with artillery attacks from land and sea and with bombing attacks, it became clear to Arafat that the Israeli Government would continue to intensify the pressure until the evacuation of the PLO forces from Beirut.

On 4 August 1982, the Israeli forces mounted a limited attack on the city, capturing two southern districts and completing the occupation of the Beirut international airport. At the same time they exerted pressure westwards along the vital Comiche el-Mazra’a highway from the area of the Museum. The tactical implications of these moves were not lost on the PLO leadership, who became more and more aware of the untenable situation in which they found themselves.

Meanwhile, Philip Habib continued his efforts for the evacuation of the PLO, with the main problem which he encountered being the unwillingness of the Arab states to accept the PLO evacuees.

On 12 August 1982, Israeli air attacks were mounted for some eleven hours on West Beirut. These attacks prompted the President of the United States, Mr. Ronald Reagan, to phone the Israeli Prime Minister, Mr. Mena-chem Begin, personally and to express his concern about them.

Mr. Begin issued orders for an immediate cease-fire, and considerable criticism was directed in the Cabinet and in public against Ariel Sharon, the Minister of Defence. He was accused of exceeding the terms of reference which had been laid down by the Cabinet. He found himself isolated in the Cabinet with only one Minister supporting him. The debate which took place in the Cabinet reflected a widespread feeling which received expression in the public debate on the war, that the Minister of Defence had on a number of occasions acted without sufficient authority from the Government and that on more than one occasion had presented it with a fait accompli. Once again, Ariel Sharon was at the centre of a public storm about military decisions and operations.

Gradually Philip Habib managed to negotiate arrangements covering the evacuation of PLO and Syrian forces from Beirut and the transfer of PLO personnel to those Arab countries which agreed to absorb them. In part this was accomplished with the help of Saudi Arabian pressure and promises of economic aid to the host countries. In all, some 14,000 Syrians, PLO, and Palestinian Liberation Army personnel were evacuated from Beirut under the supervision of the Multinational Force composed of U. S. Marines, and French and Italian troops. Of these, some 8,000 PLO personnel were evacuated by sea to eight Arab countries, while Arafat with part of his headquarters was moved to Tunis. The Syrian forces, the remnants of the 85th Brigade, were evacuated by land along the Beirut-Damascus highway to the Bequa’a Valley in east Lebanon. By the first week in September the evacuation had been completed.

At the end of August 1982, elections took place in the Lebanese parliament for a new President, and Bashir Gemayel, the leader of the Christian Phalangists, the only candidate presented, was elected. He was due to assume the presidency from Elias Sarkis on 23 September. However, on 14 September, while Bashir Gemayel was conducting a staff conference in the Phalangist headquarters in Beirut, the building in which the conference was taking place was blown up by a 200-kg. explosive which had been introduced into the building. Bashir Gemayel’s lifeless body was found in the ruins. With his passing, the hopes which attended his election—that he would succeed in creating a strong independent government in Lebanon which would maintain close relations with Israel—evaporated. Bashir Ge-mayel had many enemies, both in Lebanon and elsewhere, but all the indications are that the act was planned by the Syrians and perpetrated by Bashir Gemayel’s enemies within the Lebanese Christian camp.

Syria has always been jealous of her special position in Lebanon, and indeed never recognised Lebanon’s independence. Hence the prospect of a strong government in Beirut under Bashir Gemayel was irreconcilable with the Syrian approach, which called, in effect, for the existence of a vassal state in Lebanon, under the indirect control of Syria.

Following the murder of Bashir Gemayel, Defence Minister Ariel Sharon, with the approval of the Prime Minister, ordered the Israel Defence Forces to enter West Beirut. The Government of Israel announced that this move was taken for the purpose of preventing the outbreak of intercommunal strife and massacres. At a later stage, Ariel Sharon announced that the purpose of the operation was to clear out the remnants of the PLO. He maintained that 2,000 such operatives had stayed behind in West Beirut with large quantities of equipment and ammunition.

Two days following the entry of the Israel Defence Forces into West Beirut, both Sharon and General Eitan, the Israeli Chief of Staff, announced in interviews to the press that all the centres of control in West Beirut were in the hands of the Israel Defence Forces, and that the Palestinian refugee camps were surrounded. For some weeks, the Israel Defence Forces had been negotiating with the Lebanese Army, urging it to accept responsibility for the Palestinian refugee camps. Until Bashir Gemayel’s murder, the Lebanese forces had assumed responsibility for a number of camps, but after his assassination they stopped doing so.

On 15 September 1982, the Israeli General Officer Commanding in Beirut, acting under the instructions of the Minister of Defence, coordinated the entry into two Palestinian refugee camps, Shatilla and Sabra, of Lebanese Phalangist forces. These camps were in fact urban districts: one of them had some 2,000 buildings. The purpose of the entry of the Phalangists was to root out the remainder of the PLO forces which were believed to be inside the camps.

On 16 September, in the evening, these forces entered the camps, after having been warned by Israeli officers to ensure that no civilians be harmed in the course of the operation. The approval by the Israeli Cabinet of the operation was given shortly after the Lebanese Phalangist forces had in fact entered the camps. Sounds of shooting in the camps were heard by the Israeli and Lebanese forces in the area, but they were assumed to be the sounds of battle between the PLO forces and the Phalangists. However, soon the grisly picture emerged, when it became evident that the Phalangist forces had carried out a massacre, killing hundreds of defenceless men, women and children. As the confused picture became clearer on the morning of 17 September, General Amir Drori, the GOC Northern Command, summoned the representatives of the Phalangists and demanded that they withdraw from the camps. They did so on the morning of Saturday, 18 September.

The story of the massacre shocked Israel. Throughout the world there was a wave of protest, and Israel and the Jewish people abroad were faced by waves of hatred and incitement which recalled the dark years of antiSemitic outbursts. World Jewish opinion was aroused, and in Israel the opposition parties demanded an emergency meeting of the Knesset, the establishment of a State commission of inquiry, and the resignation of the Prime Minister and the Minister of Defence. They had warned against the decision to enter West Beirut, and maintained that the fact that Israel had announced that it was assuming responsibility for law and order in West Beirut placed on it a degree of indirect responsibility in respect of the tragic events which had taken place in the Palestinian camps. Furthermore, the permission given to the Phalangist forces to enter the camps was seen to be a major error on the part of those who had taken that decision.

Initially, Mr. Begin resisted the public pressure to establish a commission of inquiry, maintaining that it would suffice to appoint an investigator without the authority granted under the law to a formal commission of inquiry. The Minister of Energy in Mr. Begin’s Government, Mr. Yitzhak Berman, and another member of the ruling Coalition Liberal Party voted in the Knesset against the Government and supported the call for a commission of inquiry. Mr. Berman resigned from the Cabinet.

The National Religious Party and also the Tami Party, both members of the ruling coalition, demanded a formal inquiry, thus Jeopardising the majority of the Government in the Knesset should their demand not be met. The public demand in the country for the establishment of a commission of inquiry reached its climax in a mass protest rally which took place in Tel Aviv with the participation of 400,000 people. Some 10 percent of the total population of Israel came to this rally, which was in all probability the largest ever seen in Israel. In the light of the growing demand for a formal inquiry, both in Israel and throughout the world, Mr. Begin retracted, and a commission of inquiry was established under the chairmanship of the President of the Supreme Court, Justice Yitzhak Kahan, with the participation of a member of the Supreme Court, Judge Aharon Barak, and Major-General (res.) Yona Efrat.

The committee deliberated for several months and heard the testimony of a large number of witnesses, including the Prime Minister, the Minister of Defence and other members of the Cabinet. In February 1983, the report of the commission was published. It faulted the Prime Minister, for, in effect, a lack of effective control on his part; the Minister of Defence; the Chief of Staff; the GOC Northern Command, General Drori; the GOC forces in Beirut, Brigadier-General Amos Yaron; the Director of Military Intelligence, General Yehoshua Saguy; and the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mr. Yitzhak Shamir.

In its conclusions, the commission called for the resignation of the Minister of Defence, the dismissal from his post of the Director of Military Intelligence, and the removal from a command position for three years of Brigadier-General Yaron. These recommendations were implemented by the Government, although Mr. Begin decided to retain Mr. Sharon in the Cabinet as a Minister without Portfolio. Mr. Moshe Arens, Israel’s Ambassador to the United States, replaced Mr. Sharon as Minister of Defence.

A week after the murder of Bashir Gemayel, his brother Amin was elected to the position of President of Lebanon and sworn into office in his place. Unlike his brother, he did not arouse any great enthusiasm in the Christian Lebanese Front and amongst the Phalangist forces. He was known for his close relations with Syria and for his reservations about the maintenance of close relations with Israel, in contrast to the policy of his brother Bashir. It looked as if the Israeli plan that would lead to formal peace with Lebanon had come to naught.

In the meantime, the Multinational Force of U. S. Marines and French and Italian troops—which had departed with undue haste before the termination of its mandate after the evacuation of the Syrian and PLO forces from the city—returned. Its numbers were doubled to some 3,000 troops. The Israeli forces withdrew from Beirut, handing over to Lebanese forces and troops of the Multinational Force.

Meanwhile, Lebanon was racked once again by internecine, intercommunal fighting, when bloody outbreaks broke out in the northern city of Tripoli, which was under the control of Syrian forces, between pro-Syrian and pro-PLO supporters. The communal strife which had characterised the relations between the Christian and Druze communities in the Shouf Mountains erupted, with entire communities being driven out of their villages, and the Israeli forces in the area being hard pressed to stop the fighting and maintain uneasy cease-fires.

The Israeli and Lebanese governments opened negotiations with U. S. participation, which were held alternately in Halde near Beirut and Kiryat Shmoneh in northern Israel, or in Natanya. The Israeli demands, as presented at the conference, were for a withdrawal of all foreign forces from Lebanon, namely Syrian, PLO and Israeli forces; the establishment of adequate security anangements in southern Lebanon to ensure that it would never again become a base for PLO attacks on northern Israel; and the creation of a de facto normalisation of relations between Lebanon and Israel, including freedom of travel, tourism, trade and other links, and the maintenance of Government representative offices in the respective countries.

During these talks, the Israeli negotiators withdrew from their initial demand to maintain Israeli-manned warning outposts on Lebanese soil. Arrangements were negotiated for joint Israeli-Lebanese Army patrols to be active in southern Lebanon, and for Israeli reconnaissance overflights and sea patrols to take place over Lebanese air space and along the Lebanese coast.

Israel’s demands included the retention of Major Sa’ad Haddad (the commander of a mixed Christian and Shi’ite Moslem force which had cooperated with the Israel Defence Forces in fighting the PLO) as commander of the southern Lebanese area—namely, for a distance of 25 miles from the Israeli border, within the framework of the Lebanese Army. This problem became a major issue in the negotiations, with the Lebanese Government refusing to recognise Major Haddad, whom they regarded as a renegade, and the Israeli Government maintaining its opposition to abandoning a man who had proved to be a trusted friend in difficult and adverse times.

These negotiations were being conducted in an atmosphere of uncertainty as to the intention of the Syrians to withdraw their forces. The Israelis were adamant in their refusal to withdraw unless adequate arrangements were made for the withdrawal of the Syrian and PLO forces from Lebanon. The Syrians indicated to the American Government that they would withdraw subject to being assured of an Israeli withdrawal. They later changed this position to one which limited itself to undertaking to consider such a withdrawal after examining the Israeli-Lebanese agreement if and when reached.

Meanwhile tension was growing as Syria tested the vast quantities of brand-new equipment which was supplied to it by the Soviet Union and reinforced its front line facing the Israeli forces in the Bequa’a Valley.

At this point the Soviet Union, which had been comparatively passive during the Israeli operation in Lebanon, stepped up its involvement in the crisis. In February 1983 the Russians installed SAM-5 surface-to-air missiles, with a range of some 300 kms., in two major sites in Syria, thus giving them adequate range to cover the skies over Tel Aviv, and the eastern half of Cyprus, including the area over the Levant Sea in which the U. S. Sixth Fleet is deployed, and southwards to the area of Amman in Jordan. These sites were manned by Soviet troops and protected by them in fenced-off areas which became in effect extraterritorial Soviet territory in Syria. This Soviet move, which was regarded with considerable concern by the United States, Israel and Jordan, was interpreted as a Soviet reply to the massive destruction of Soviet-built ground-to-air Syrian missiles in the Lebanese war, as a move to bolster Syrian morale, and as a Soviet reaction to the stationing of U. S. Marines in Beirut within the Multinational Force— a move which Soviet commentators tended to interpret as the creation of a base for the U. S. Rapid Development Force in the Middle East. Once again the Soviet Union had moved in order to heighten tensions in the Middle East, to threaten Israel, and to embarrass the United States in its efforts to achieve a peaceful solution to the Arab-Israeli problem.

The negotiations with Lebanon took place against the background of a move by the President of the United States, Ronald Reagan, to advance the Israel-Arab negotiations on the basis of his so-called Reagan Plan, which was designed to encourage Jordan to enter negotiations with Israel. This plan, while rejecting the idea of an independent Palestinian state on the West Bank and in Gaza, called in effect for Jordan to act for the Palestinian people in negotiations which envisaged territorial compromise in the West Bank and Gaza between Israel and Jordan.

King Hussein had made it clear that he would not endanger himself by entering negotiations with Israel without receiving a mandate from the PLO to act for the Palestinians. In April 1983, after prolonged negotiations between King Hussein and Yasser Arafat, the PLO, following its Palestine National Conference which had been held in Algiers a month earlier, rejected out of hand the Reagan Plan—which had previously been rejected by the Israeli Prime Minister, Mr. Begin—and withheld from King Hussein authority to enter into negotiations with Israel.

At this point, angered by Arafat’s rejection, despite the urging of the Saudi Arabians and King Hussein, of the Reagan Plan and of Jordanian negotiations with Israel, the United States gave expression to its frustration and disappointment in a statement by the U. S. Secretary of State, George Shultz, questioning the sole representation of the Palestinians by the PLO.

An additional complicating factor was the strained relations between Syria and the PLO leadership. Syria, backed by the Russians, was a major element in encouraging opposition to any inclination on the part of Arafat to authorise King Hussein to enter into negotiations with Israel, and indeed threatened military action should the Jordanians enter into such negotiations. Syria— with its ominous threats of military action, its massive acquisition of weapons from the Soviet Union, its military association with the Soviet Union, with surface-to-air missile units stationed on Syrian soil in addition to 4,500 Soviet military advisers—was gradually becoming the main force in the Middle East opposing all the moves in the Arab world to open further negotiations with Israel.

Thus the end of April 1983 found the Middle East in a stalemate as far as Jordanian-Israeli negotiations were concerned, because of Arafat’s unwillingness to split the PLO’s ranks on such an issue, while at the same time, with the help of the United States, slow but sure progress was being made in bilateral negotiations between Israel and Lebanon on the future relations of the two countries. This against the background of ominous increased Soviet involvement in the conflict in the area.

In May 1983, an Israeli-Lebanese agreement was reached. It called for the withdrawal of all foreign forces from Lebanese soil and made arrangements for various forms of cooperation between Israel and Lebanon, including the opening of negotiations six months after the agreement came into force, in order to establish normal relations between Israel and Lebanon. Provisions were made for a mechanism that would guarantee Israel against the re-creation of a terrorist base in southern Lebanon. Under the agreement. Major Sa’ad Haddad was to become deputy commander of the southern region, responsible for intelligence. It further provided for the activation of joint Israeli-Lebanese patrols in Lebanon, although Israeli forces would not be allowed to be stationed inside the country.

The agreement left many questions unanswered, and indeed, despite the fact that it was a second agreement between Israel and an Arab country, it did not arouse any enthusiasm with Israel, because it was assumed that the agreement was being made with a weak Lebanese Government whose authority did not extend far beyond the municipal confines of Beirut. In June 1983, both the Knesset in Israel and the Lebanese Parliament ratified the agreement.

Linked to this agreement was the issue of the withdrawal of all foreign forces from Lebanon; it was stipulated that should such a withdrawal not take place, the agreement would be void. The key now lay with Syria. However, despite considerable Arab and international pressure, Syria, justifying itself on an all-out condemnation of the Israeli-Lebanese agreement—which President Assad maintained was prejudicial to the security of Syria—made it quite clear that it had no intention of withdrawing.

Syria was obviously strengthened in its hard line by the considerable political pressure being exerted on the Israeli Government, in favour of either a partial withdrawal of the Israeli forces from the Shouf Mountains and the area of Beirut to the line of the Awali River or, in regard to other political elements, a total withdrawal from Lebanon. The Syrians, as is the case with most dictatorships, failed to understand the various nuances within the political struggle in Israel. President Assad assumed that the steady bleeding of Israel by inflicting casualties, the ongoing economic burden that Lebanon was creating for Israel, the increased number of days that reservists had to serve—all this, coupled with the political pressure within Israel, would lead to an Israeli withdrawal without a concurrent Syrian withdrawal being required.

The American Government exercised its influence, activating Saudi Arabia and moderate Arab countries, in an effort to obtain Syrian agreement to withdraw. Secretary of State Shultz made a number of visits to the area and discussed the matter in difficult and tough negotiations with President Assad. This took place against the background of growing strife in the Shouf Mountains between the Druze community and the Christians. Bloody outbreaks took place between them, and the only element preventing a major disaster was the Israeli forces.

In Israel, objections were voiced against its troops being used to police an area between feuding Lebanese forces, with resultant casualties for the Israelis. The Government of Israel began to consider redeployment along the Awali River, excluding the Shouf Mountains and the area of Beirut from the area held by its forces, thus lightening its burden. However, as the significance of the Israeli partial withdrawal dawned on the Americans and Lebanese, Israel found itself, paradoxically, being pressured not to withdraw. It was feared that a partial withdrawal would mean a de facto partition of Lebanon, with the Syrians holding the Beqa’a Valley in the north of Lebanon and the Israelis holding the area south of the Awali River. Furthermore, there was a suspicion that the Lebanese Army was incapable of taking over from the Israel Defence Forces and maintaining order between the warring Lebanese factions, and that the Multinational Force of some

3,000 American, French, Italian and British troops was not big enough to cope with the situation that would result from the Israeli withdrawal. Israel found itself under considerable international pressure—American, Lebanese and European—not to withdraw from Lebanon until an arrangement for total withdrawal of all forces could be made.

However, the losses incurred by the Israeli forces through attacks by Lebanese and Palestinian terrorist groups, which had infiltrated back into the area of Beirut and other parts of Lebanon, and the economic burden of maintaining its troops, led the Israeli Government to decide in principle on a redeployment of its forces, with a view to shortening its lines, thereby reducing the burden and ensuring greater security for its troops. The actual execution of such a plan is at this time the subject of negotiations between the Israeli Government and the United States and Lebanese governments. It became evident that prospects of a Syrian agreement to withdraw appeared to be very dim indeed. Unless such a Syrian agreement could be achieved, the prospects of a de facto partition of Lebanon into Syrian and Israeli zones of influence, with the central Lebanese Government being propped up for a long period of time by the Multinational Force, were very real indeed.

Meanwhile, a further development occurred in the area that was bound to affect events relating to the Palestinian problem. For months, under American and moderate Arab pressure, King Hussein had been urged to come to the negotiating table with Israel. He was unwilling to do so without being given a mandate for such negotiations from the PLO. There were many elements in the PLO who favoured such a change in policy. King Hussein negotiated on this issue over a long period of time with Yasser Arafat, but the results of the Palestine National Council meeting in Algiers and the growing pressure from the extreme elements against any form of compromise on the drastic policy set out by the Palestinian Covenant (which in fact called for the annihilation of Israel) led to the failure of the Hussein-Arafat talks.

The prolonged negotiations between Arafat and Hussein, however, brought to a head an internal struggle within the ranks of the PLO. The dispersal of the PLO, the distance of its headquarters in Tunis from the planned area of conflict on the Israeli borders, the conversion of Arafat to an itinerant politician with little to offer, the internecine strife between the various Arab and Palestinian elements in northern Lebanon—all combined to create an atmosphere of frustration and disenchantment with the leadership of Arafat. In late June and early July 1983, armed revolution against Arafat’s leadership broke out. This revolution took place within the ranks of the A1 Fatah organization, the largest component within the PLO, led by Arafat. The ostensible reason for the hostilities was dissatisfaction with military appointments that Arafat had made in order to strengthen his hold on the organisation, but the real reason was a demand on the part of the anti-Arafat forces for a more extreme policy based on military struggle rather than on political efforts.

World History

World History