At Isurava, Horii met unexpected resistance. From ground so high that the Japanese referred to it as "Mt. Isurava”, the Australians poured down a heavy fire that stopped him for three days. On August 28 his casualties were so heavy that a Japanese officer wrote in his diary, "The outcome of the battle is very difficult to foresee.”

That evening, at his command post on a neighbouring hill lit by fires in which his men were cremating their dead, Horii learned the reason for the repulse: the untrained Australian militiamen of the 39th Battalion had been reinforced by experienced regulars of the 21st Brigade, brought home from the Middle East. Horii ordered his reserve forward from Kokoda and on the afternoon of August 29 launched an onslaught that drove the

Defenders out of Isurava. By the evening of August 30 the Australian forces were in full retreat up the Kokoda Track.

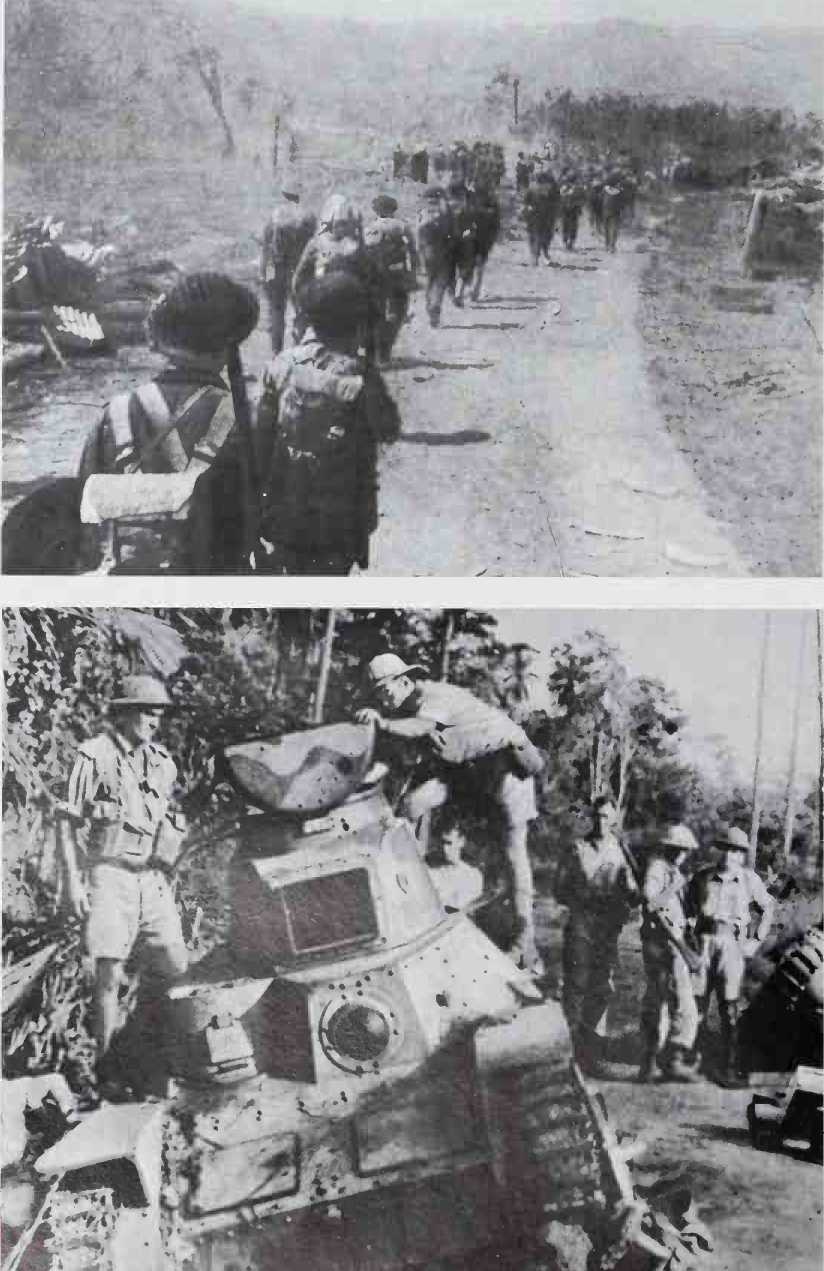

General Horii subjected them to constant pressure, using alternately his 144th (Colonel Masao Kusunose) and his 41st (Colonel Yazawa) Infantry Regiments. Following closely to keep the Australians off balance he gave them no time to prepare counter-attacks, outflanking them from high ground, and bombarding them with his mountain guns at ranges they could not match. His troops crossed mountain after mountain, "an endless serpentine movement of infantry, artillery, transport unit, infantry again, first-aid station, field hospital, signal unit, and engineers”.

Between the mountains, swift torrents roared through deep ravines. Beyond Eora Creek the track ascended to the crest of the range, covered with moss forest. "The jungle became thicker and thicker, and even at mid-day we walked in the halflight of dusk.” The ground was covered with thick, velvety green moss. "We felt as if we were treading on some living animal.” Rain fell almost all day and all night. "The soldiers got wet to the skin through their boots and the undercloth round their bellies.”

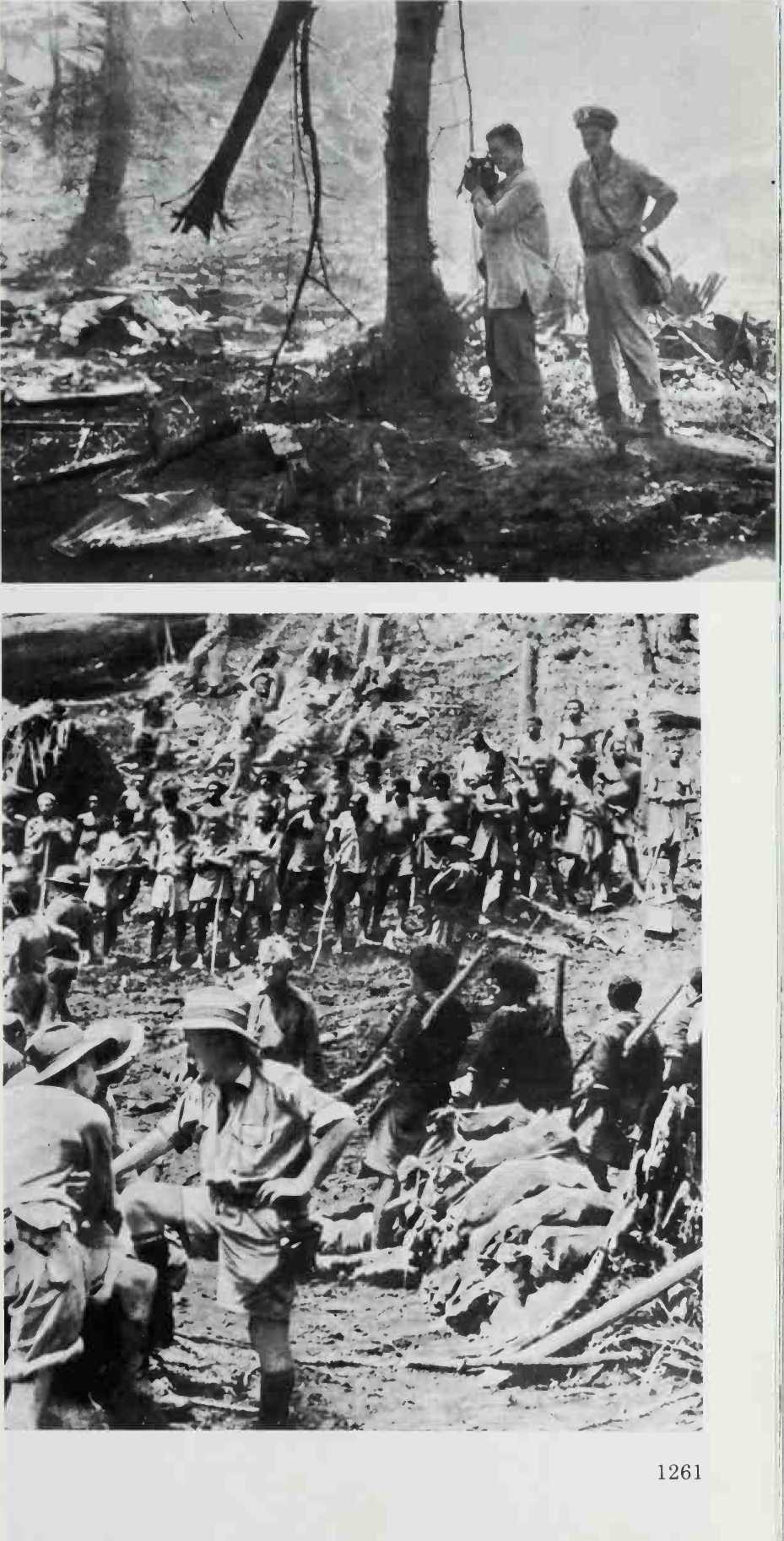

Coming down from the crest on the morning of September 7, slipping and sliding on the muddy downward track, the Japanese vanguard found the Australians preparing to make a stand on the ridge behind a ravine at Efogi. During the morning Allied planes came over, strafing and bombing, but in the thick jungle did little damage. The following day before dawn the Japanese attacked, and by noon, in bitter hand-to-hand fighting that left about 200 Japanese and Australian bodies scattered in the ravine, they pushed the defenders off the ridge.

In mid-September the Australians, reinforced by a fresh brigade of regulars, the 25th, tried to hold on a ridge at loribaiwa, only 30 miles from Port Moresby, so near that when the wind was right the drone of motors from the airfield could be heard. But on September 17 the Japanese, who still outnumbered them, forced them to withdraw across a deep ravine to the last mountain above the port, Imita Ridge.

At loribaiwa, Horii halted, his forces weakened by a breakdown in supply and by Allied air attacks. In any case, he had orders not to move on Port Moresby until an advance could be made by sea from Milne Bay.

World History

World History