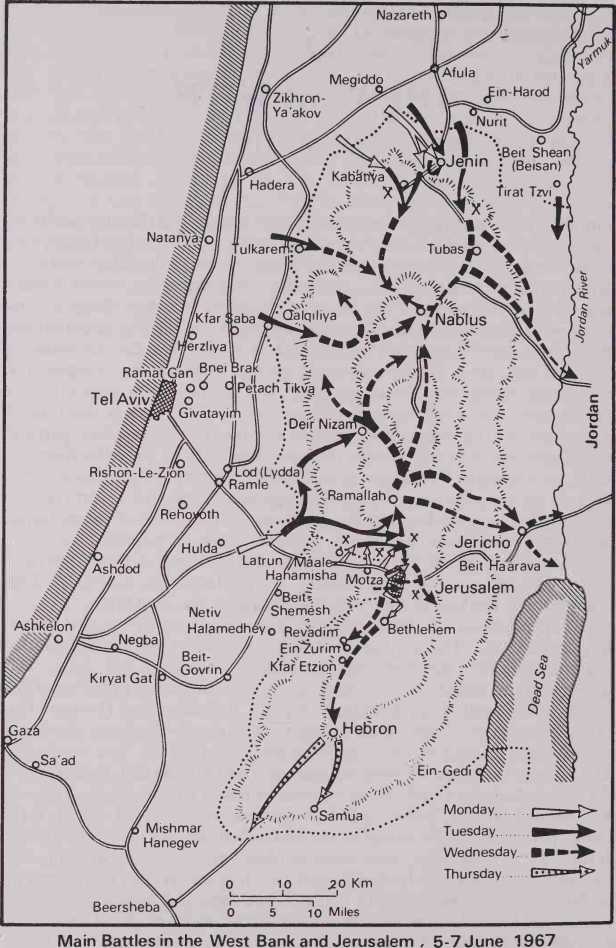

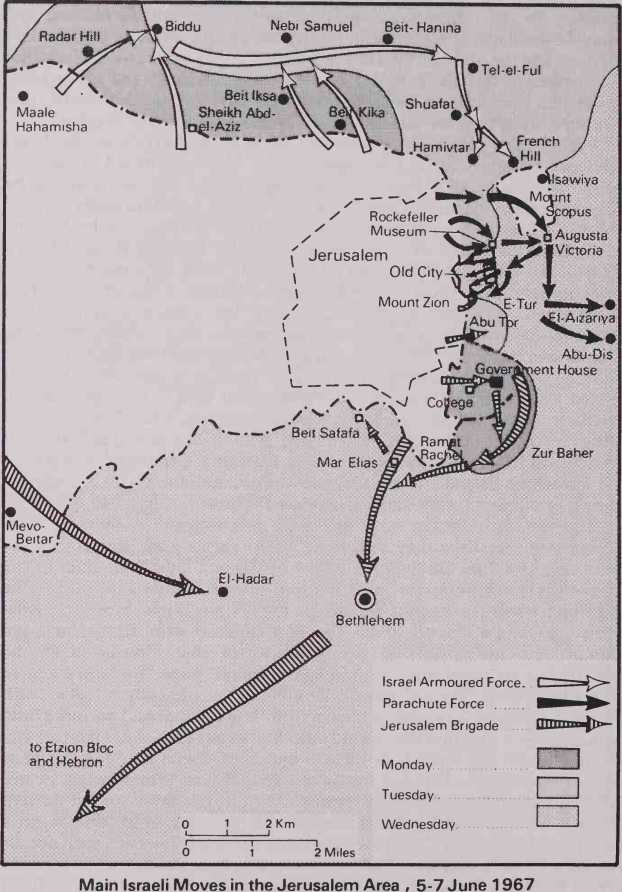

Unlike in 1956, the Sinai Campaign of 1967 constituted but one theatre of conflict in a war that was waged on three fronts. The war with Jordan was fought on territory of a very different character from the Sinai, and over cities and towns of a religious and historic connotation for Jews, Moslems and Christians. The structure of the territory in the West Bank area is based on a central mountainous ridge running from north to south; to the east of this, there is a steep drop to the River Jordan and, farther south, to the Dead Sea. Here, few roads permit passage from the west bank of the river towards the Mediterranean coast: the mountainous nature of the terrain makes it a difficult proposition for an army facing determined opposition. To the west of this ridge lies a fertile, populated plain, parts of which were controlled by Jordan no more than eight or ten miles from the coast, at the point where the coastal plain commenced its gentle climb towards the central ridge. Passage through and across this western area is comparatively easy, while artillery positions on the hills and ridges facing the coastal resort areas and towns covered centres of population such as Natanya, Herzliya and Tel Aviv. Farther south, a spur of Israeli territory thrust into the area held by Jordan — the Jerusalem Corridor. This Corridor was flanked by high ridges fortified by the Jordanians.

The dispositions of the Jordanian Army were based on two major defensive sectors. The northern sector comprised the region of Samaria, and was based on the main cities of Nablus, Tulkarem and Jenin. The southern sector based on the Judean region extended along the spine of the Judean Hills south from Ramallah through Jerusalem and Hebron. The forward elements of the forces in both regions were deployed along the coastal strip leading to the narrow ‘waistline’ of Israel. The Jordanian Army comprised eight infantry brigades and two armoured brigades under the Commander-in-Chief, Field Marshal Habis el Majali. Major-General Mohammed Ahmed Salim, the Arab general in command of the West Front, had deployed his forces in the field as follows. Six infantry brigades defended the West Bank, with three holding the district of Samaria, two stationed in and around Jerusalem and a sixth in the Hebron Hills south of Bethlehem. A further infantry brigade was deployed near Jericho, just west of the River Jordan, while the mobile striking force of the Jordanian Army, the 40th and 60th Armoured Brigades, were held back in the area of the Jordan valley, with the 40th Brigade, commanded by Brigadier Rakan Inad el Jazi, responsible for the northern part of the West Bank and the 60th Brigade, commanded by Brigadier Sherif Zeid Ben Shaker, directed towards Jerusalem and the area south of it. (Brigadier Ben Shaker

Was one of the outstanding officers in the Jordanian Army, highly regarded by his cousin, King Hussein. He was in later years to become the Commander-in-Chief of the Jordanian armed forces.) Batteries of 155mm ‘Long Tom’ guns were sited to cover Tel Aviv in the south and Ramat David airfield in the north. As Nasser moved his divisions into the Sinai and signed a pact with King Hussein, the Jordanians advanced their field artillery to the ridges covering the coastal towns and Jerusalem, and readied their armoured forces in the Jordan valley, with one brigade near Jericho and the other by the Damya Bridge, further north, with a battalion in the area of Nablus. In addition to Jordan’s 270 tanks and 150 artillery pieces, an Iraqi infantry brigade was stationed in Jordan: this was to grow within a week to three infantry brigades and an armoured brigade.

Facing these forces were elements of two Commands in the Israel Defence Forces: Central Command, under Major-General Uzi Narkiss, disposed of the 16th Jerusalem Brigade in that city, commanded by Colonel Eliezer Amitai, a reserve infantry brigade near Lod under Colonel Moshe Yotvat, and a reserve infantry brigade commanded by Colonel Zeev Shaham in the area of Natanya. Under Colonel David Elazar’s Northern Command were seven brigades, and these were responsible for the borders with three countries, Syria, Jordan and Lebanon. This deployment included a brigade covering the Lebanese border, two brigades deployed in eastern Galilee facing Syria and one brigade facing Samaria in the area of Nazareth. An armoured brigade was held in reserve for the Syrian front, while an armoured division under Major-General Peled, comprising two armoured brigades, was held in reserve in central Galilee. Held in General Staff Reserve was the ‘Harel’ Mechanized Brigade, under Colonel Uri Ben Ari, who had commanded the 7th Armoured Brigade so successfully in the 1956 Sinai Campaign, and part of 55 Parachute Brigade, under Colonel Mordechai ‘Motta’ Gur, which was being held ready for an air drop against El-Arish or Sharm El-Sheikh.

The war with Jordan came on Israel unexpectedly. A message from Prime Minister Eshkol of Israel had been sent to King Hussein on the morning of 5 June through the offices of General Odd Bull, chief of the United Nations observers, assuring him that if Jordan kept out of the fighting, Israel for its part would not initiate hostilities. However, King Hussein’s commitments under the new alliance with Egypt, and the atmosphere of hysteria in the Arab world that already made the destruction of Israel a reality in the Arab mind, joined together to force the King’s hand. He had joined the alliance with President Nasser with some misgivings. Less did he desire to join the alliance, than to be ‘odd man out’ — a situation that would label him as a traitor to the Arab cause. King Hussein had agreed, further, to appoint General Riadh of Egypt as the Commander-in-Chief of his forces. He behaved with a certain degree of hesitation because he was not completely sure of the wisdom of the step he was taking; indeed, this hesitation was to come to expression on a number of occasions during the conduct of the war. However, such doubts as King Hussein may have had were overcome by an assurance he received from President Nasser in a telephone conversation that morning (5 June)

That scores of Israeli aircraft had been downed (at which moment the Egyptian Air Force lay, unbeknown to Nasser, in smoking ruins), and that Egyptian armoured forces were pushing across the Negev in a move to join up with the Jordanian forces in the Hebron Hills. King Hussein ordered his armed forces to attack.

World History

World History