The French offensive in the Ardennes at the beginning of the war

Started out as the northern half of Joffre’s offensive into Germany and turned

Into a flank stroke into the German line of advance.

But the French adherence to tactical doctrines long out of date, and a serious under-estimate of the German numbers, led to a decisive defeat = which at least had the result of enforcing a reconsideration of those doctrines ,

On the French High Command

Peter Young

V

A German artist’s impression of the savage hand-to-hand fighting which took place during the Battle of the Frontiers, as the Germans began to push the French back toward their start lines

In the two daj - battles of the Ardennes, August 22-23, 1914, two French armies, the Third under Ruffej' and the Fourth under de Langle de Cary, met two German, the Fourth under the Duke of Wiirttemberg and the Fifth under Crown Prince Wilhelm. It was, however, far from being an equal encounter. The Germans, whose strength between Bastogne* and Thionville Joffre’s Intelligence Section had estimated on August 16 at onlj' six or seven corps with two or three cavalry divisions, actually had ten corps and two cavalry divisions. The French, who flattered themselves that they were advancing with a numerical advantage, had ten corps, with two reserve divisions and three cavalry divisions. The Germans thus had a numerical superiority over the French of 380,000 to 361,000 (200,000 in the Fifth Army and 180,000 in the Fourth to 168,000 in the Third Army and 193,000 in the Fourth).

By August 16 it was clear to the French that the main German advance was swinging round through Belgium, while to the south of Metz the Germans seemed to be on the defensive. Joffre came to the conclusion that he had the opportunity to break his enemy’s centre, and then fall upon the German right. It was his intention, therefore, to use the Third and Fourth Armies for a great thrust through Luxembourg and Belgian Luxembourg. This, his principal attack, would strike at the southern flank and the communications of the Germans who had crossed the River Meuse between Namur and the Dutch frontier. He hoped that he would be able to attack them before they could swing south and deploy for battle. The offensive of the First and Second Armies further to the south was of secondary importance, its aim being to hold the German forces, who seemed to be shifting westwards and so posing a threat to the right flank of the Third Army. Furtner north, the Fifth Army, the BEF and the Belgian army, by checking the German advance from the Meuse, were to give the Third and Fourth Armies time to develop their offensive.

Joffre sent out his orders on August 20. The Third Army was to begin its offensive movement next day in the general direction of Arlon —'The mission of the Third Army is to counterattack any enemy force which may try to gain the right flank of the Fourth Army.’

The Fourth Army was to move in the general direction of Neufchateau. Joffre telegraphed to its commander, de Langle de Cary: 'I authorise you to send strong advanced guards of all arms tonight to the general line Bertrix-Tintigny to secure the debouchment of your army beyond tbe (River) Semois.’

The eve of the great French offensive in the Ardennes found the BEF concentrated south of Maubeuge, the French Fifth Army with its forward elements on the River Sambre and on the Meuse near Dinant, the Third and Fourth close up to the Belgian frontier, astride the river Chiers, from the vicinity of Longwy to Sedan, and ready to cross the Semois river. To the south the newly-formed Sixth Army under Maunoury was keeping Metz under observation, while the First and Second Armies (Dubail and de Castelnau) mauled at Sarrebourg and Morhange had been compelled to retire.

The repulse of de Castelnau and Dubail was a poor omen, but on the 21st the French centre crossed the Belgian frontier and

Advanced some 10 to 15 miles into the Ardennes —no mean feat for the country is very difficult: rough, tree-clad hills, broken up by deep river valleys with occasional narrow belts of pasture. The French groped forward, their aeroplanes able to see nothing, their cavalry proving ineffective for reconnaissance in the forest defiles and villages. Thus on the 22nd the French columns literally ran into the Germans, who were crossing their front, and a number of separate actions developed, which are known to the French as the battles of Virton and of the Semois, and to the Germans as Longwy and Neufchateau.

The nature of the country made liaison between the various columns practically impossible, and rendered it extremely difficult for corps (still less army) headquarters to exercise any effective control over operations. Under the circumstances the Germans, who were more realistically trained than their adversaries, enjoyed a tactical advantage, which was far more important than their slight numerical advantage. Moreover, while the French were not expecting serious opposition, the Germans had no such illusions. They expected to meet an aggressive foe of a strength equal to their own, and in consequence had explored the Ardennes with Hollens’ cavalry (TV Cavalry Corps) who were ready to guide and support their advancing infantry. The French, not knowing that the Germans had Reserve corps in the line, underestimated their enemy.

Heavy rain fell during the afternoon and evening of August 21, and during the night that followed there was a heavy mist. In the early hours of the 22nd the Crown Prince’s advanced guards located French troops at Virton, Ethe and Signeul. It was still dark and the Germans halted under cover in the forward edge of the woods and dug in.

Surrounded, outnumbered — but still fighting

The French got on the move some hours later and it was already daylight when they stumbled into the German lines. In the fog V Corps under Brochin wandered into the German XIII Corps (Fabeck), which was preparing to attack. There ensued a disorganised battle, which ebbed and flowed for two hours until the fog lifted to reveal the French artillery in close support of their infantry. The Germans lost no time in bringing a heavy fire on the hapless 75s. Simultaneously the German infantry got in their attack. Panic seized the French and it was not long before V Corps, Ruffey’s centre, was beating a hasty retreat for Tellancourt, leaving each of the neighbouring corps with a flank in the air. On Ruffey’s right Sarrail’s VI Corps did well, but during the afternoon it was compelled to retire in the face of superior numbers. On the left of the Third Army the IV Corps (Boelle) became engaged at Virton and Ethe with Strantz (V Corps) and part of Fabeck’s XIII Corps. Boelle’s two divisions, fighting separate battles, though less than three miles apart, held their own, but were unable to make progress, and so left de Langle’s right flank unprotected. Gerard (II Corps),, hesitating to advance when thus exposed, made no real effort in the direction of Tintigny, but, halting on the outskirts of Bellefontaine, launched an attack eastwards bringing timely assistance to the hard-pressed IV Corps of Ruffey’s army. This altruistic action had an unhappy effect on the Colonial Corps on Gerard’s left. This was the formation to which de Langle de Cary had given the task of taking his main objective, Neufchateau. Its selection was not surprising, for not only had it three divisions, as opposed to the normal two, but it was composed largely of professional soldiers, veteran campaigners of Indo-China and North Africa. This corps d’elite pushed forward in two columns. On the right the 3rd Colonial Division advanced through the Forest of Neufchateau by way of Rossignol and on the left a mixed brigade, advancing through the Forest of Chiny by way of Suxy. The columns, separated by a broad and well-nigh impassable stretch of woods, were expected to converge for the final assault on Neufchateau.

Expecting little opposition except perhaps from patrols or advanced guards, the 3rd Colonial Division ran into Pritzelwitz’s VI Corps in the woods north of Rossignol and launched a series of furious bayonet charges. Five French battalions were taking on nine German battalions, with three squadrons of dismounted cavalry. The French column tried in vain to break through, while the Germans deployed and worked round both their flanks. It was as if the French had learned nothing since the days of Waterloo, when their columns had withered before the musketry of British and German infantry fighting in line. The very courage and zeal of the French was their undoing. The loss of officers was particularly heavy. Early in the action three of the five battalion commanders were mown down by a burst of machine gun fire as they conferred at the roadside. Confusion reigned. The leading brigade fell back on Rossignol to await —in vain —the support of the second brigade of the division. The failure of Gerard’s II Corps to advance had left the right flank of the Colonial Corps in the air. The German 22nd Brigade, belonging to Pritzelwitz’ VI Corps, striking in from the east towards St Vincent now compelled the second brigade of the French corps to turn 90 degrees instead of continuing the march on Rossignol. Hard pressed though it was this formation might have rendered some assistance to its fellows had it not been that the narrow River Semois divided them. Though not more than 15 or 20 yards wide, its banks were marshy and vehicles could only cross by the stone bridge at Breuvanne, one and a quarter miles south of Rossignol. By keeping this under a heavy artillery fire the Germans effectively cut the Colonial Division in two, depriving the defenders of Rossignol of all relief Surrounded and outnumbered, the survivors fought on with admirable devotion. In the dusk the regimental colours were buried among the burning houses of the shell torn villages. When the last wave of German infantrymen broke over Rossignol the division had suffered 11,000 casualties. The divisional commander and one of the brigade commanders were dead and the other brigade commander was a wounded prisoner. Most of the divisional artillery was in German hands.

It was Gerard’s failure to advance that had permitted the German 22nd Brigade to intervene with such effect, but it was by no means the sole reason for the catastrophe that overwhelmed the 3rd Colonial Division. Throughout the day the 2nd Colonial Division remained at Jamoigne, barely three miles distant, in Army Reserve. Early in the afternoon General Lefevre, the corps commander, ventured to ask de Langle de Cary’s permission to send the division into action, but permission did notcome through until night had fallen. Leblois, the divisional commander, sent forward a battalion to create a diversion, but that was all. It cannot be said that either Lefevre or Leblois displayed much initiative, and the latter was removed from his command a few months later for his incapacity.

The left-hand column of the Colonial Corps, some 6,000 strong, advanced harassed by Uhlans, and under the surveillance of German aircraft. Nevertheless, the brigade under Gaullet reached the neighbourhood of Neufchateau without undue difficulty. Here they met the Hessians and Rhinelanders of the XVIII Reserve Corps under Steuben, and gave a good account of themselves against odds of two to one. Gaullet held on until nightfall without word of the other column. Neither corps nor army headquarters enlightened him as to events at Rossignol and, threatened with encirclement, he fell back during the night. The 5th Colonial Brigade regained its start line, south of the Semois, unmolested. Gaullet had done rather well as the breakdown of the opposing forces at Neufchateau reveals. For in opposition to the six French battalions the Germans had

Bayonets fixed and rifles at the ready,

French infantry move forward to begin their attack

12, with one German regiment and squadron of cavalry against one troop, one German battalion of engineers against one company and nine German batteries (54 77-mm field guns) against three batteries (12 75-mm field guns).

Another German brigade remained in reserve. Given a fair chance the hardened French colonial troops were more than a match for the ardent but inexperienced German reservists.

Captured without a shot

Roques’ XII Corps scored an initial success at St Medard against one of Steuben’s brigades, but perceiving that Neufchateau remained in German hands, it halted though there was nothing much between it and Recogne, about seven miles north of St Medard. Poline’s XVII Corps got through the forests during the morning, to find open country between it and its objective, Ochamps, where the Germans were firmly ensconced. A typical French attempt to storm the place by a brusque attack broke down. A German counterattack came in from the east, and fell on the French communications. Wagons and guns, nose to tail, blocked the road through the Forest of Lunchy, where the corps train was awaiting the fall of Ochamps. Surprised by part of XVIII Corps under Schenck, the French broke and fled in confusion after the briefest resistance. One group of artillery broke out, but for the most part the guns, unable to deploy, were captured without a shot fired. Soon the whole corps was in panic-struck flight. It was not rallied until it was far beyond its original start line. De Langle de Cary’s

Army, like Ruffey’s, had a breach the width of the front of a whole corps in its centre. After heavy fighting Eydoux’ XI Corps had driven part of Schenck’s corps from Mais-siu, but hearing of the departure of Poline’s men, Eydoux prudently evacuated the place and took up a defensive position on the heights to the south. He at last had carried out his mission.

For the French it had been a day of disaster. For two corps (I Colonial and XVII) had been severely mauled, and if those of Gerard and Roques (II and XII) were more or less intact it was largely because they had made no serious effort to carry out their missions. Two corps of the German Fourth Army had not been engaged at all. Pritzelwitz’s victory at Rossignol had cost him dear, and Stuben had paid an even heavier price, without enjoying the same measure of success, at Neufchateau. From the German point of view the honours of the day had gone to Schenck’s XVIII Corps, which had routed the French XVII Corps and also fought the XI Corps to a standstill.

The reports that reached the army commanders and seeped through to Joffre were both sparse and garbled. At the end of the day Ruffey still thought he had not five but three corps to deal with. De Langle de Cary, still unaware of the presence of VIII Corps and VIII Reserve Corps, nevertheless gave the Commander-in-Chief a fairly realistic account of the day’s work: 'All corps engaged today. On the whole results hardly satisfactory. Serious reverses in the region of Tintigny [Rossignoll and Ochamps. Successes before St Medard and Maissiu cannot be main-

'Without good tactics, the best strategy must be ineffective’

German artillerymen take a brief rest on the side of the road during their advance through the Argonne

Tained. Have given orders to hold the front Hondvemont/Bievre/Paliseul/Bertrix/ Straiment/Jamoigne/Meix-devant-Virton.’

To this Joffre, not the man to abandon his offensive lightly, replied: 'Information collected, taken as a whole, shows only approximately three army corps before your front. Consequently you must resume your offensive as soon as possible.’

De Langle received this order early on August 23, and made a real effort to carry it out, but the task allotted to him was hopeless, and when night fell his army, thoroughly shaken by the events of the last three days, so far from having made progress, was actually further to the rear. Joffre now realised that the Fourth Army had shot its bolt, and with his approval shortly after midnight on the 24th de Langle de Cary gave orders for 'a withdrawal beyond the River Meuse’.

Thus ended the second great French offensive —in utter failure. The German army commanders for their part were not slow to trumpet their success. The Crown Prince received a telegram from his father, the Kaiser, reading: 'Congratulations in the first victory which, with God’s help, you have won so splendidly. I award you the Iron Cross, Classes I and II. Convey to your brave troops my thanks, and those of the Fatherland. Well done! I am proud of you. Your affectionate father, Wilhelm.’

But, in fact, things were not quite so rosy as the German commanders painted them, for, though mauled, neither the French Third nor Fourth Army was broken.

The battle left Joffre still labouring under his early delusions with regard to

German numbers. He attributed the failure of the offensive to two divisions of the Third Army having allowed themselves to be surprised, and to a division of the Fourth Army falling back and dislocating the whole line. This had led to the Colonial Corps being violently attacked and having to give way. He attributed the German advances in the north to their having drawn troops from their centre. On August 25 he telegraphed to Monsieur Messimy, the Minister for War: 'I am studying the means of stopping this [rearward] movement by abandoning as much ground as is necessary and preparing a new manoeuvre, the object of which will be to oppose the march of the enemy on Paris.’ One can only admire Joffre’s dogged resolution, but the disaster must be attributed at least in part to his miscalculation of the German strength and intentions. In the Ardennes his troops, handicapped by a false tactical doctrine, had little chance in an offensive against the better trained Germans, who also enjoyed a considerable numerical advantage.

To his credit it must be said that Joffre was quick to discern the weakness of that fatal French tactical idea that infantry should attack head down, regardless of the enemy’s fire and without artillery support. As early as August 24 he issued an instruction to all the French armies: Each time that it is necessary to capture a point d’appui (strongpoint) the attack must be prepared with artillery, the infantry must be held back and not launched to the assault until the distance to be covered is so short that it is certain the objectives will be reached. Every time that the infantry has been launched to the attack from too great a distance before the artillery has made its effect felt, the infantry has fallen under the fire of machine guns and suffered losses which might have been avoided.

When a point d’appui has been captured, it must be organised immediately, the troops must entrench, and artillery must be brought up.

The French, in their blue coats and red trousers, paid a heavy price to learn lessons which were taken for granted by their British allies. Without good tactics the best strategy must be ineffective. If the company commanders fail how shall the generals succeed? The unfortunate infantry were horribly mangled in the Ardennes fighting. A company commander, Grasset, describes his ordeal near Virton on August 22:

The sun was scorching, yet my watch showed only nine in the morning. The hours were passing but slowly. It seemed to me that we had been there for a long, long time. My company was sustaining heavy losses. Evidently its action was hampering the enemy, who concentrated the combined fire of his infantry, artillery, and machine guns on us. We were surrounded by a heavy cloud which at times completely veiled the battlefield from our eyes...

Little Bergeyre sprang up, shouted: 'Vive la France!’ at the top of his voice, and fell dead. Among the men lying on the ground, one could no longer distinguish the living from the dead. The first were entirely absorbed by their grim duty, the others lay motionless, having entered eternal rest in the very attitude in which death surprised them.

Not for

The first time — invasion from the east

The changing fortunes of war.

Left.'a quiet French square witnesses French artillery departing forwar.

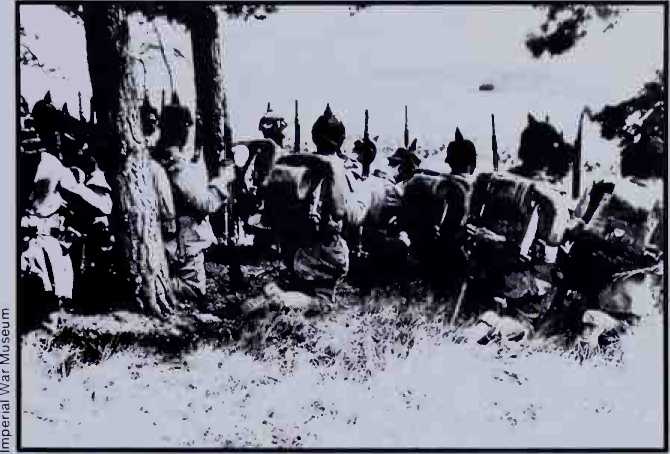

Se/ow/eft.'the same square witnesses achurch service held bytheinvading Germans. Below: German infantry wait on a wooded hilltop for the signal for their next advance into France

The wounded offered a truly impressive sight. Sometimes they would stand up bloody and horrible-looking, amidst bursts of gun-fire. They ran aimlessly around, arms stretched out before them, eyes staring at the ground, turning round and round until, hit by fresh bullets, they would stop and fall heavily.

Heart-rending cries, agonising appeals and horrible groans were intermingled with the sinister howling of projectiles. Furious contortions told of strong and youthful bodies refusing to give up life.

One man was trying to replace his bloody, dangling hand to his shattered wrist. Another ran from the line holding the bowels falling out of his belly and through his tattered clothes. Before long a bullet struck him down.

We had no support from our artillery! And yet, there were guns in our division and in the army corps, besides those destroyed on the road. Where were they? Why didn’t they arrive? We were alone. I was wondering, in my anxiety, whether we were going to lose all our men on the spot.

Another young officer who had his baptism of fire in the Ardennes was Lieutenant Erwin Rommel of the 124th (Wiirttemberg) Infantry, belonging to the Crown Prince’s Fifth Army. In the attack on Bleid near Longwy, he was scouting forward of the line with three other men when he saw 15 or 20 Frenchmen twenty paces away, 'in the middle of the highway drinking coffee, chatting, their rifles lying idly in their arms. They did not see me’. The 5th Company of the French 101st Infantry Regiment did not believe, it seems, in tak

Ing such elementary precautions as posting sentries! Rommel continues: 1 withdrew quickly behind the building. ITas I to bring up the platoon? No! Four of us would be able to handle this situation. I quickly informed my men of my intention to open fire. We quietly released the safety catches; jumped out from behind the building; and standing erect, opened fire on the enemy nearby. Some were killed or wounded on the spot; but the majority took cover behind steps, garden walls, and wood piles and returned our fire. Rommel’s platoon then came up and assaulted a building which was the main French position.

On signal the 2nd Section opened fire. I dashed forward to the right with the 1st Section —over the same route I had passed over a few minutes before with the platoon — across the street. The enemy in the house opened with heavy rifle fire mainly directed at the section behind the hedge. The assault detachment was now sheltered by the building and safe from the hostile fire. The doors gave way with a crash under heavy blows of the battering ram. Burning bunches of straw were thrown onto the threshing floor, which was covered with grain and fodder. The building had been surrounded. Anyone who had taken a notion to leap out would have landed on our bayonets. Soon bright flames leapt from the roof. Those of the enemy who were still alive laid down their arms. Our casualties consisted of a few slightly wounded.

The point of this passage is that while the French were still employing the tactics of the middle, if not the beginning of the 19th Century, the Germans were already versed in much more modern 'Fire and Movement’ tactics. The point of this tactical dissertation is simply to suggest that the battles of the Ardennes were lost as decisively at pre-1914 manoeuvres as in the offices where Plan 17 was concocted. One thing was certain: with the Fourth Army back across the Meuse, Plan 17 was dead.

Further Reading

King, J. C., The hirst woria War (New York; Harper 1972) .

Rommel, F-M. Erwin, Infantry Attacks (Quan-tico, Virginia 1956)

Spears, Maj-Gen. Sir Edward, Liaison 1914 (London 1968)

Thoumin, R., The First World War (London 1963)

Tyng, S., The Campaign of the Marne, 1914 (London 1935)

BRIGADIER PETER YOUNG (retd), DSO, MC and two bars, FSA, RFHistS, was born in 1915 and educated at Monmouth School and at Trinity College, Oxford. Commissioned in 1937, he served with distinction throughout the Second World War. He was wounded during the Dunkirk campaign, volunteered for special service and sent more than four years with No 3 Commando, taking part in such important raids as those against the Lofotens and Dieppe. When the war ended he was commanding the 1 St Commando Brigade. He was a student at the Staff College, Camberley, in 1946, and from 1953 to 1956 commanded the 9th Regiment of the Arab Legion. He is ex-Head of the Military History Department at the RMA Sandhurst, and has written numerous books and articles.

World History

World History