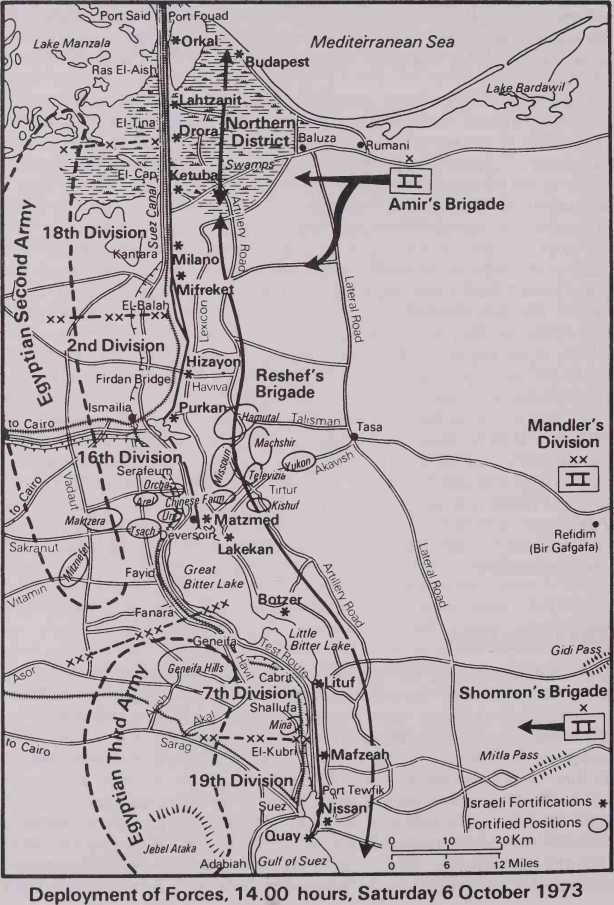

The total strength of the Egyptian Army (one of the largest standing armies in the world) included some 800,000 troops, 2,200 tanks, 2,300 artillery pieces, 150 anti-aircraft missile batteries and 550 first-line aircraft. Deployed along the Canal were five infantry divisions and a number of independent brigades (infantry and armour) backed by three mechanized divisions and two armoured divisions. Each infantry division included a battalion of tanks for every one of the three brigades, making a total of 120 tanks in every infantry division. The three mechanized divisions included two mechanized brigades and one armoured brigade, a total of 160 tanks per division. The two armoured divisions were composed of two armoured brigades and one mechanized brigade, with a total of about 250

Tanks per division. There were also independent tank brigades, two paratroop brigades, some 28 battalions of commandos and a marine brigade.

The Egyptian Second Army was responsible for the northern half of the Canal and Third Army for the southern half. The Second Army front was

Held by the 18th Infantry Division from Port Said to Kantara and the Firdan Bridge; by the 2nd Infantry Division from the Firdan bridge to the north of Lake Timsah; and by the 16th Infantry Division from Lake Timsah to Deversoir at the northern end of the Great Bitter Lake. The dividing line between the two armies ran through the centre of the Great Bitter Lake. Third Army had under command the 7th Infantry Division, responsible for the sector of the Bitter Lakes to half-way down the southernmost section of the Suez Canal, and the 19th Infantry Division south to, and including, the city of Suez. Each of the assaulting infantry divisions was reinforced for the crossing by an armoured brigade, drawn in part from the armoured and mechanized divisions.

Every move in the first phase, which was to take place between 6 and 9 October, had previously been planned and prepared to the minutest detail. Ten bridges were to be thrown across the Canal, three in the area of Kantara, three in the area of Ismailia-Deversoir and four in the area of Geneifa-Suez. A division would cross in a sector some four to five miles wide. The first wave would be entrusted with seizing and holding the earth ramparts; when the second wave reached these, forces of the first phase were to advance 200 yards and remain in their positions; within an hour of the attack, third and fourth waves would move to join the first and second waves. As soon as the support units of the attacking battalion had crossed, the entire force would advance. The first waves of the attacking infantry divisions were to establish themselves one to two miles in depth, following which special infantry units trained for the purpose were to attack and capture the strongpoints. Each bridgehead was ultimately to be five miles wide and three and a half miles deep. They were to remain so until the arrival of the tanks and the artillery, when they would be enlarged to a base of ten miles wide and five miles deep.

At H-Hour on 6 October, 240 Egyptian aircraft crossed the Canal. Their mission was to strike three airfields in the Sinai, to hit the Israeli Hawk surface-to-air missile batteries, to bomb three Israeli command posts, plus radar stations, medium artillery positions, the administration centres and the Israeli strongpoint known as ‘Budapest’ on the sandbank east of Port Fouad. Simultaneously, 2,000 guns opened up along the entire front: field artillery, medium and heavy artillery and medium and heavy mortars. In the first minute of the attack, 10,500 shells fell on Israeli positions at the rate of 175 shells per second. A brigade of frog surface-to-surface missiles launched its weapons, and tanks moved up to the ramps prepared on the sand ramparts, depressed their guns and fired point-blank at the Israeli strongpoints. Over 3,000 tons of concentrated destruction were launched against a handful of Israeli fortifications in a barrage that turned the entire east bank of the Suez Canal into an inferno for 53 minutes.

At 14.15 hours, when the aircraft had returned from their bombing missions, the first wave of 8,000 assault infantrymen, moving exactly as they had been trained dozens and (in many cases) hundreds of times, stormed across the Canal. Along most of the front, they crossed in areas not covered by fire from the Israeli strongpoints or organized for action; in

Most places they avoided such fortifications, bypassing them and pushing eastwards. At the same time, commando and infantry tank-destroyer units crossed the Canal, mined the approaches to the ramps, prepared anti-tank ambushes and lay in wait for the advancing Israeli armour.

In some areas Israeli resistance was heavy; in other areas it was comparatively light. Initial Egyptian estimates had been that the crossing would cost some 25,000-30,000 casualties, including some 10,000 dead, but their casualties in the initial crossing, which totalled only 208 killed, were lower than any Egyptian planner had imagined. (In the Second Army area, the crossing went according to plan with few hitches, but in the area of Third Army there were some problems caused by the Israeli rampart proving to be wider than the Egyptians had estimated and also by the nature of the soil at the southern end of the Suez Canal, which, instead of disintegrating under the high-pressure water hoses, tended instead to become a morass of mud.) The commander of one of the two infantry divisions in Third Army who encountered strong Israeli reaction later recounted that he lost 10 per cent of his men in the initial assault, although he had estimated that he would lose 30 per cent. He related the story of a lone Israeli tank that fought off the attacking forces for over half an hour, causing very heavy casualties to his men when they tried to storm it. When they finally overcame it the Egyptian general recounted how, to his utter amazement, he found that all the crew had been killed with the exception of one wounded soldier, who had continued to fight. He described how impressed he and his men were by this man, who, as he was being carried away on a stretcher to a waiting ambulance, saluted the Egyptian general.

Less successful were the Egyptian commandos, who were landed in depth along the entire length of the front from the area of Port Fouad in the north down to Sharm El-Sheikh at the southern tip of the Sinai Peninsula. Their purpose was to harass the inevitable Israeli counterattacks, and tank-hunting units were ordered into position to prevent the Israeli tanks from deploying according to plan on the ramps between the strongpoints. A special operation in this phase was the crossing of the Great Bitter Lake by 130 Marine Brigade: its amphibious vehicles attempted to bypass Israeli forces and link up with commando forces in the area of the Mitla and Gidi Passes. However, fourteen helicopters loaded with Egyptian commando forces were shot down by the Israeli Air Force, and Israeli forces throughout the Sinai were rapidly organized to deal with the threat.

World History

World History