I HE FIRST FOOTHOLDS established on D-Day were quickly expanded to a bridgehead some 80 miles long. Men by the tens of thousands poured in. Allied air coverage was supreme. A week after D-Day, Churchill visited the beaches. He steamed through what he called “a city of ships.”

When Field Marshals von Rundstedt and Erwin Rommel, commanders of the German forces, realized they had failed to prevent the landing, they planned to withdraw their forces and estabhsh a defensive hne farther to the east, a move that would shorten their supply lines.

Hitler, however, would not permit any withdrawal. Von Rundstedt and Rommel met with him at Soissons, about halfway between Paris and the Belgian border, 11 days after the Alhed landings. “You must stay where you are,” Hitler told his generals.

They, in turn, warned him that it was disastrous

To hold a line so far to the west. Hitler dismissed the warning and told them of a secret weapon he was about to unveil—the flying bomb. The Fuehrer believed it would change the course of the war.

The generals urged Hitler to use the new weapon against the invasion beaches or the ports along the British coast that were supplying the Allied forces. Hitler had a different strategy. He planned to bombard London instead, believing this strategy would “convert the English to peace.”

The flying bomb that Hitler talked of was a small, pilotless craft that flew a preset course. Each carried a one-ton package of explosives.

The miniature craft flew at an altitude of about 2,000 feet, travehng 350 miles an hour. Its maximum range was about 150 miles. When its fuel supply gave out, it dived for ground, exploding on impact.

These weapons rained death and destruction upon London for the next two and a half months. They arrived at random intervals, so Londoners never felt safe. The Germans called the weapon Ver-geltungswaffe Bins (Vengeance Weapon One). To the Americans and British, they were known as V-ls.

The V-1 was powered by a special jet engine, a pulse jet, which made a low, stuttering sound. Because of its distinctive sound, the British nicknamed the weapon the “buzz bomb.”

The reign of terror did not reduce London to ruins nor did it come close to defeating the British, but it killed many people and frightened millions more.

To thwart the V-1, the British installed antiaircraft guns along the coast so the small planes could

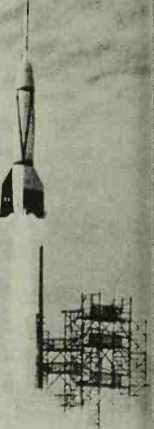

BRITISH FIGHTER PLANE (RIGHT) TRAILS A V-2 ROCKET ACROSS SOUTHERN ENGLAND. (United Press International)

Be fired upon as they approached. Fighter planes were dispatched to shoot them down over the English Channel. A ring of big helium-filled balloons, each resembling a blimp, went up around London. But still the V-ls got through.

Advancing Alhed armies eventually captured the V-1 launching sites in France, ending the attacks. More than 40,000 people, mostly civilians, were killed or injured by the V-ls.

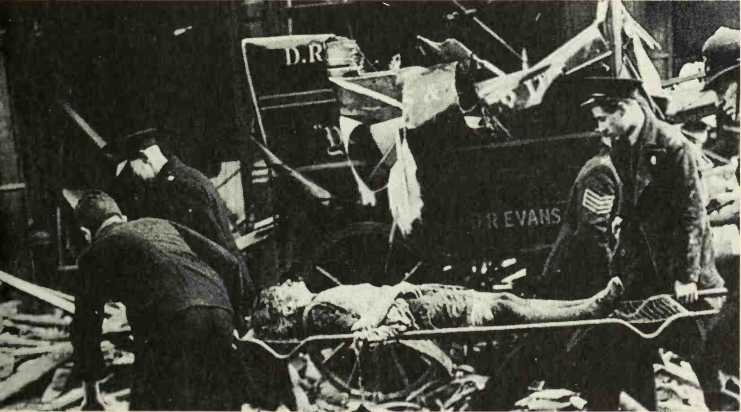

A GIRL VICTIM OF A ROCKET BOMB IN LONDON. (United Press International)

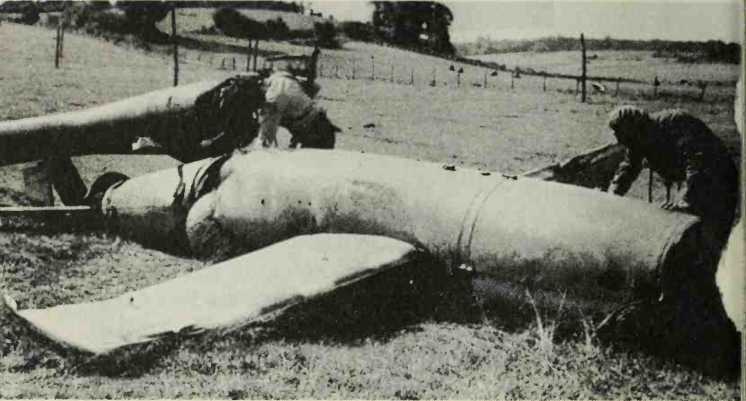

A V-2 THAT CRASHED AFTER TAKEOFF IS EXAMINED BY A CANADIAN SOLDIER (RIGHT) AND A MEMBER OF THE FRENCH RESISTANCE MOVEMENT. (United Press International)

The terror was not over, however. From bases in the Netherlands, the Germans began firing an advanced version of the V-1, called the V-2. The first of these was launched in September of 1944.

The V-2 was much faster than the V-1, capable of a speed of 3,300 miles per hour, meaning that it traveled faster than the speed of sound and arrived without the slightest warning. No one was aware of its presence until there was a deafening explosion and an entire building or city square was blasted out of existence. The V-2 ranks as one of the most frightening weapons of war ever devised.

The Germans mounted V-2 launching platforms on railroad flatcars and moved them from place to place. Not until the Alhed troops captured the sites where the V-2s were being manufactured did the attacks end. That was in March, 1945. In all, more than 12,000 V-2s hit England, causing almost 10,000 casualties.

The V-ls and V-2s never accomphshed what Hit-

Ler expected, nor did they change the course of the war. Nevertheless, when the last of the vengeance weapons had fallen. Allied military experts breathed a sigh of rehef. What would have happened, they wondered, had the use of V-ls and V-2s begun earlier, even three or four weeks earlier? They surely would have crippled Alhed plans for the invasion and they could have extended the war for months, perhaps even a year or more.

Hitler had begun developing these weapons late in the 1930s, not long after he gained control of the Nazi party. They would have been available for his use much earlier had it not been for a strange twist of fate.

The story of the V-ls and V-2s begins after World War I with the Treaty of Versailles. The treaty barred the Germans from producing guns or artillery, but the treaty said nothing about the development and production of rockets for mihtary use.

The Germans decided to take advantage of this loophole. A civilian engineer, Wernher von Braun, who had experimented with rockets as a child, was named to head Germany’s rocket production project.

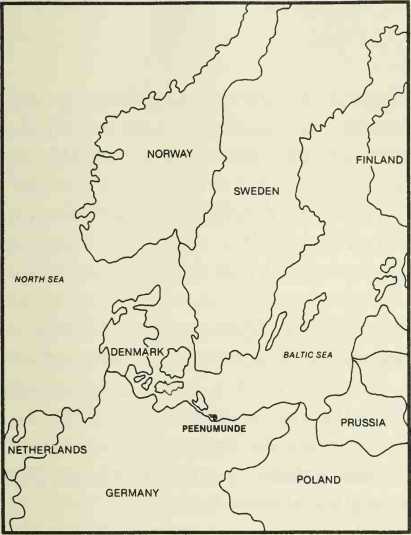

In 1937, the Society for Space Travel, a group headed by von Braun, founded a research center at Peenemunde, a small island in the Baltic Sea just off Germany’s northern coast. Peenemunde was farming and dairy country, a quiet and peaceful region of thatch-roofed homes and green meadows.

Von Braun’s first successful experiments involved the use of rockets in connection with aircraft takeoffs. These eventually led to the development of jet-powered aircraft.

With that work behind him, von Braun began the development of a long range, pilotless rocket that would be able to carry a two-ton warhead. Launched in a high arc to a height of more than 20 miles, it would travel to its target at twice the speed of sound, its hquid fuel propellant carrying it a distance of about 200 miles. It could be neither seen nor heard until its warhead struck the ground, exploding like an aerial bomb.

In March 1939, just a few months before he was to order the invasion of Poland, Hitler witnessed a test of the rocket. He was not impressed. It was so unpredictable in flight that the engineers who launched it were not sure where it was going to come down.

The work at Peenemiinde continued in utmost secrecy, however, with more than 1200 engineers assigned to the project. By late 1942, V-2 rockets were being test fired on a regular basis, but because the weapon sometimes flew erratically, more work was needed.

The Allies were aware that something was afoot at Peenemiinde. Danish fishermen told of an unusual amount of activity on the island. Reconnaissance planes were assigned to take photographs of the area.

In May 1943, one such plane took a baffling photo at Peenemiinde. It showed a tiny blurred speck in the shape of a miniature airplane parked on an inclined ramp. In the vicinity of the ramp, the ground was blackened as if by a hot blast.

At about the same time that British intelhgence agents were puzzhng over the photograph, Stanley

PEENEMUNDE IN NORTHERN GERMANY, CENTER FOR ROCKET RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT. (Neil Katine, Herb Field Art Studio)

Lovell, an American intelligence officer, came upon some equally bewildering information concerning Peenemiinde. Based in Washington, Lovell was the Director of Research and Development of the Office of Strategic Services, the OSS, the highly secret sabotage and intelligence arm of the U. S. government.

Lovell was reading copies of messages that had been received from OSS agents around the world, when one caught his eye. It was from an agent in Switzerland and it reported a conversation the agent had had with a worker who had escaped from German-occupied France to Switzerland.

The report ended with these words: “Workman told following improbable story: Said he was forced to guard casks of water from Rjukan in Norway to island of Peenemiinde in Baltic Sea.”

Why would a French lab worker have been guarding water? Lovell asked himself. Then he recalled a scientific discussion he had attended the week before. During the discussion, the term “heavy water” had been used. It had been described as an element necessary to the production of a nuclear or atomic bomb. Heavy water would, indeed, be water worth guarding.

Lovell then learned that Rjukan was the site of one of the biggest hydroelectric plants in all of Europe. As such, it was one of a handful of plants capable of producing heavy water. If the Germans were sending heavy water to Peenemiinde, Lovell concluded, then Peenemiinde must be where Germany was developing its atomic bomb.

Lovell recalled Hitler saying, “We will have a weapon to which there is no answer.” An atomic bomb, Lovell knew, could be such a weapon. When Lovell reported his theory to his superiors, they were skeptical. But leading atomic scientists of the day beheved him.

Lovell was flown to London to meet OSS officials there. They were impressed with what he had to say. If the Germans were developing an atomic bomb at Peenemiinde, they had to be stopped immediately.

On the night of August 17, 1943, a huge fleet of four-engined Lancaster bombers took to the air. The next day, the British Air Ministry issued this official communique:

Last night aircraft of the Bomber Command made a heavy attack in bright moonlight on the research and development establishment at

Peenemunde, 60 miles northeast of Stettin. The establishment is the largest and most important of its kind in Germany. A great number of aircraft were encountered along the route. Several were destroyed.

Later it was learned that enemy fighters had battered the raiders along a great part of the route, and 41 of 300 bombing planes had been lost. But those that managed to reach the target ripped the research center apart.

Daily newspapers in the United States spoke of the destruction that had been wrought at “Germany’s mystery plant.” More than a thousand people were killed in the raid and all above-ground installations were leveled.

While the bombing planes derailed the V-1 and V-2 programs, they did not put an end to them. Production of the weapons continued underground.

It was not until after the war that the mystery of the heavy water being shipped to Peenemunde was unraveled. Lovell learned from the chief of the hydroelectric plant at Rjukan that, for reasons of security, guards were told that heavy water shipments from the plant were headed for Peenemunde. While the ships carrying the heavy water came close to Peenemunde, they never actually landed there but continued to the German port of Wolgast. From Wol-gast, the heavy water was sent by rail to plants where nuclear research was going on.

Thus, by trying to deceive the Alhes, the Germans made the mistake of focusing attention on Peenemunde. The bombing raid that followed has

(LEFT) DR. WERNHER VON BRAUN, ONE-TIME HEAD OF GERMANY’S ROCKET DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM, PICTURED IN THE UNITED STATES IN 1977. (National Aeronautics & Space Administration) (RIGHT) TESTING A V-2 ROCKET AT CAPE CANAVERAL, FLORIDA, IN 1950. (National Aeronautics and Space Administration)

Been ranked as one of the most important of the war.

There is one other strange twist to this story. After the Alhed forces captured Peenemiinde and the war in Europe had ended, Wernher von Braun and more than 125 other German scientists who had worked on the V-1 and V-2 programs joined forces with American scientists who were working on the U. S. rocket program. Thus, the development of Hitler’s terrible vengeance weapons eventually led to man’s first landing on the moon and many of the other space achievements that followed.

World History

World History