On JUNE 6, 1944, the biggest invasion in history was launched across the English Channel into France. Almost 3,000,000 American, British, and Canadian troops took part. They were supported by a fleet of more than 5,000 ships and 11,000 aircraft.

Minesweepers went first, clearing the coastal waters of explosive charges. Battleships, cruisers, and destroyers blasted enemy fortifications with their gunfire. Bombers attacked from the sky.

Paratroopers cut railroad lines, blew up bridges, and seized landing fields. Gliders brought in jeeps, small tanks, and light artillery.

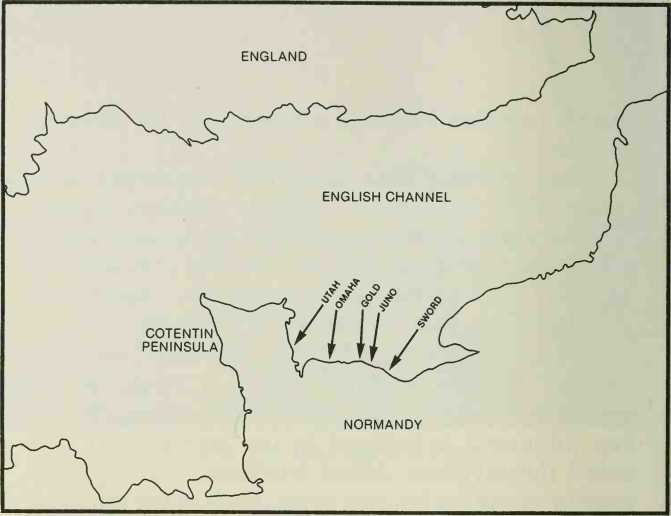

At 6:30 A. M., under gray skies, the first waves of infantry waded ashore at carefully-planned points along 50 miles of French coastline in the province of Normandy. Americans landed at beaches with the code names Utah and Omaha. At Utah, only pockets of resistance were encountered, but at Omaha the

A PORTION OF THE D-DAY INVASION FORCE. (U. S. Navy)

Germans fought fiercely.

Gold, Juno, and Sword were the code names of beaches where the British landed. At Juno, they were supported by Canadian units. British and Canadians were successful on all three beaches, although at points the Germans fought with the savagery the Americans faced at Omaha.

In the days that followed, the Alhes poured hundreds of thousands more men into the ever-widening beachheads. Tons of supplies and tens of thousands of vehicles were landed along with the troops.

A long struggle remained. France and other German holdings throughout Europe, and Germany itself, still had to be fought for and won. But the Allies had gained a vital foothold from which the final assault on Hitler’s “Fortress Europe” could be launched.

There were many reasons how and why the invasion had succeeded against a tough and experienced enemy. One fact, however, stands out: the Normandy invasion came as a surprise to the German defenders.

Field Marshal Carl Gerd von Rundstedt, who commanded the German forces in Western Europe, held back from committing all of his ground troops and firepower. This was not the real invasion, he thought. Von Rundstedt was waiting for a second Allied thrust, an assault that never occurred.

Von Rundstedt believed that the “real” invasion was to take place at Calais, about 100 miles to the northeast, which was exactly what the Allies wanted von Rundstedt to believe! In the months that preceded the invasion. Allied intelligence agents had gone to enormous lengths to establish in the minds of the German High Command that the assault on Normandy was merely a feint, a soft jab before the knockout punch. And they succeeded.

The Alhes began to plan an assault across the English Channel as early as 1942. Deciding exactly where to land was the first order of business.

Calais was the obvious choice. The distance across the English Channel at Calais was only about 20 miles, while the Normandy beaches were more than 75 miles from England. But the terrain inland from Calais was a problem. The many rivers and streams that crisscrossed the area would have slowed the progress of the attacking force.

Brittany, the large peninsula at France’s northwest corner, was also considered as the invasion target. But it was too far from England.

Normandy had several advantages. It was in easy range of fighter planes and aircraft needed for ground support. It offered plenty of space for tactical

ALLIED LANDING ZONES ON D-DAY. (Neil Katine, Herb Field Art Studio)

Maneuvering. And the area selected for the landings was flanked by the Seine and Orne Rivers, which would offer some measure of natural protection.

Once the Allies decided upon Normandy, the next task was to keep it a secret. If the Germans knew in advance where the Alhes were going to land, they would mass troops and guns against the invasion force, making it easy to push the troops back into the sea.

At first the Alhes considered launching an attack on Calais at the same time as the Normandy assault. The Calais attacking force would be much smaller and only for the purpose of drawing the Germans’ attention from what was happening at Normandy. But this plan would never fool the Germans. They would realize from the small number of troops and landing craft that it was not the real invasion force.

Then the Alhes developed the “Big Lie” to feed the Germans:

The main Allied assault would be launched against Calais, and it would come six weeks after the landings at Normandy. The Normandy attack was to be a decoy to divert the Germans from the main attack that was to follow.

The Allies figured if they could get the Germans to beheve this lie it would go a long way toward making D-Day a success. The Germans would hold back some of their forces from Normandy, waiting for the attack on Calais.

To entice the Germans into beheving the lie, the Allies pretended to be making invasion preparations much farther to the east, opposite Calais. The build up for the real attack was to be kept secret.

The Alhes wanted the Germans to think the U. S. First Army would be landing at Calais. Troops of the First Army were transferred to the coastal region of England just opposite Calais.

A commanding officer had to be assigned to the First Army Group, one who would seem believable in that post to the Germans. The name of General Omar Bradley was suggested, but Bradley was scheduled to land in Normandy with the real assault forces. If the Germans saw Bradley in France, they would realize something was wrong.

Then it was decided to choose General George Patton to lead the First Army Group. Patton was already in charge of the Third Army, but the Third Army was not scheduled to land in France until more

Than a month after D-Day. By that time there would be no need for the deception.

To transport the First Army and its equipment to Calais, a fleet of fake landing craft was created to be displayed along the rivers of southeast England. It included countless dummy landing craft for tanks, known as “Bigbobs,” and dummy landing craft for the troops, called “Wetbobs.”

The Bigbobs, 160 feet long and 30 feet wide, were made of painted canvas strips lashed to steel tubing. They were equipped with wheels so they could be pushed from the assembly sheds to the water. Once in the water they were supported by floats.

The Wetbobs were smaller and made of inflatable rubber. Twenty Wetbobs, rolled up like carpets, could be carried in a single truck.

After more than 250 Bigbobs and Wetbobs had been placed in position, camouflage experts were taken aloft to look them over. They decided the dummy craft didn’t look real enough. To make them appear more genuine, clotheslines were strung on some of them with washing hung out to dry.

When a reconnaissance plane approached and was picked up on radar, coastal antiaircraft batteries were automatically put on alert and Allied fighter squadrons were sent into the air. But once the Bigbobs and Wetbobs were in place, these plans were revised. Fighter planes were kept on the ground so as not to scare a reconnaissance plane away. And although the antiaircraft fired at the plane, the gunners were told to shoot too low.

When a German reconnaissance plane returned home, its cameras contained hundreds of photo-

U. S. TROOPS ABOARD A LANDING CRAFT BEFORE INVASION OF FRANCE.

(U. S. Navy)

Graphs of landing craft in Dover Harbor. German intelligence experts examining the pictures would draw the conclusion that the craft must be intended for landings at Calais. Certainly they couldn’t be intended for Normandy; it was too far away for such boats.

To add to the deception, various units of the First Army broadcast fake messages to each other. The Allies knew that the Germans monitored such radio traffic.

Often the fake messages would comment on local weather conditions. This made them sound more authentic. And when fog blanketed the English Channel between Calais and the southeast coast, broadcasts were cancelled, giving the Germans the impression that training exercises had been called off because of bad weather.

At one time in the weeks before D-Day, 20 units of the First Army were transmitting fake radio messages. Since most of this radio traffic originated only a short distance from the enemy forces, less than 50 miles in most cases, it was very easy to monitor.

In the early years of the war, the Alhed forces had worked diligently on the development of fake tanks, vehicles, and guns to deceive the Germans. All this knowledge and experience was to be put to use in promoting the D-Day hoax. Take the case of the Sherman tank, one of the most formidable of Allied weapons. Dummy Sherman tanks were available in three different versions—folding, inflatable, and mobile.

The folding model was made of plywood sections that were painted in standard tank colors and bore tank markings. The parts for several folding models could be carried in one truck and assembled on the site.

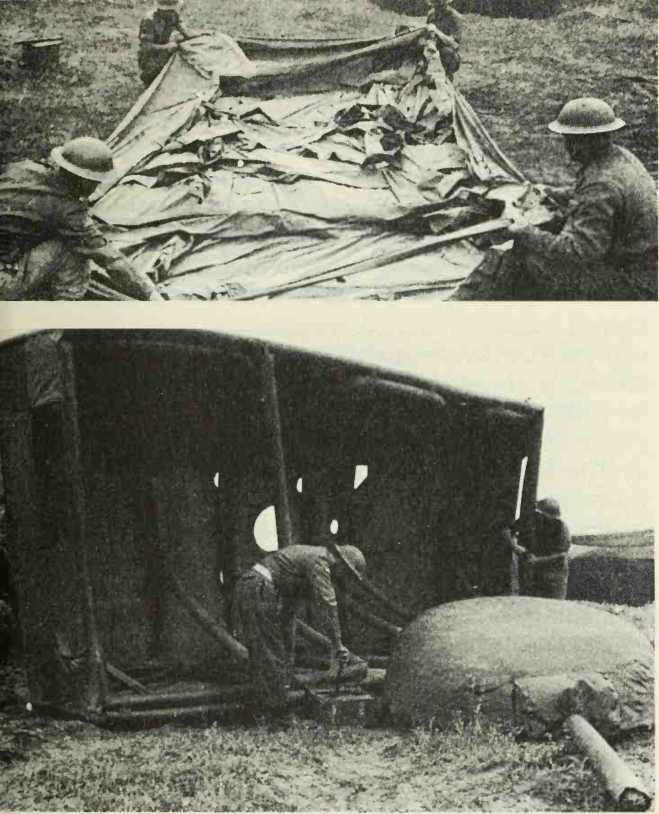

The inflatable models were made of lengths of rubber tubing. When filled with air, the tubing became a rigid tank skeleton. By fastening on strips of

(TOP) BODY ASSEMBLY FOR A DUMMY TANK IS LAID OUT BEFORE INFLATING. (National Archives) (MIDDLE) BRITISH SOLDIERS INFLATE THE TURRET OF A DUMMY TANK. INFLATED BODY ASSEMBLY IS IN BACKGROUND. (National Archives) (BOTTOM) INFLATED DUMMY TANK IS PLACED IN POSITION UNDER CAMOUFLAGE NETTING. (National Archives)

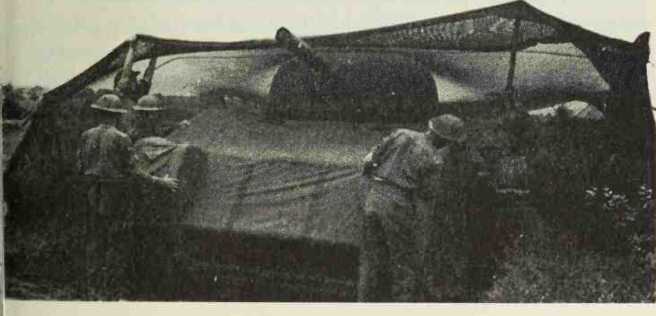

Canvas, the result was an object with a tank shape. It did not look very much hke a real tank up close, of course, but from the air it was difficult to tell an inflatable from the genuine article. Not only were tanks created in this fashion, but also big trucks, armored vehicles, guns, and even aircraft.

The mobile Sherman tank consisted of a tankshaped framework of light steel tubing covered with canvas. The various features of a tank—the caterpillar treads, the turret, etc.—were painted on the canvas. Fitted over the body of a jeep, it gave the appearance of a tank moving into position quickly.

The deception had several defects, however. The fake tanks could not cross ditches or climb steep banks. They did not send up thick clouds of dust when crossing open terrain. And they did not make the loud rumbhng sounds real tanks made. But these flaws didn’t matter. From distances of 350 yards and more, the mobile Sherman tank dummies looked authentic.

In the spring of 1944, when German reconnaissance planes made daily flights over southeast England, their cameras recorded what appeared to be enormous buildups of troops and equipment. There were tent cities where troops of the First Army were quartered. Tanks, vehicles, and guns were lined row upon row in vast staging areas.

Meanwhile, farther to the west, where the real invasion force was being assembled, strict security precautions were observed. A ten-mile strip of coasthne became a restricted zone. No one was allowed to enter or leave the area without permission from top authority.

All new buildings in the area used for housing or training the invasion force were camouflaged by painted patterns of foliage to hide them from German reconnaissance planes. Tents were kept darkened at night. Only smokeless stoves could be used in cookhouses. All troops were issued khaki-colored towels and underclothing. White cloth could too easily be spotted from the sky.

The Big Lie also directly involved General Montgomery, who had previously headed the British Eighth Army in North Africa and now commanded the British forces who were being massed for the D-Day assault.

Clifton James, an actor, was called upon to impersonate Montgomery. James looked a great deal like the general except for a missing middle finger on his right hand. That was camouflaged by having him wear gloves.

James was assigned to Montgomery’s staff to study the general at close range. At night in his room he practiced the way Montgomery walked and carried himself. He took to clasping his hands behind his back during a discussion the way Montgomery did. He frequently carried a Bible, another trait for which Montgomery was well known.

James had long conversations with Montgomery so he could become familiar with the quality and cadence of his voice. The general had a habit of selecting his words with great care. James developed that habit.

When James felt he was ready, he was given a test. A group of senior intelhgence officers assembled and James was brought in to address them. The

Officers marveled at how closely the actor resembled Monty and how well he duphcated the general’s crisp man-to-man style of speaking.

Toward the end of May, with D-Day about a week away, James was given a crucial assignment. He was flown to Gibraltar, the British fortress and seaport near the southern tip of Spain that guards the entrance to the Mediterranean Sea. There he was met at the plane and driven to Government House in an open car. The Alhes wanted to be sure that the many German agents in Gibraltar learned of the famous general’s arrival. Sir Ralph Eastwood, the governor and a close friend of Montgomery’s, was in on the secret.

During his stay in Gibraltar, Montgomery’s impersonator spoke often of a mysterious “Plan 300,” which he described as an assault on the Mediterranean coast of France that would be mounted across the Mediterranean from the northern coast of Africa. Eastwood arranged for certain Spanish businessmen, known to be in contact with German agents, to overhear James discussing Plan 300. When James left Gibraltar his destination was Algiers, capital of Algeria on Africa’s north coast.

The Alhes did not care whether the Germans believed that Plan 300 might or might not be real. (It was not.) Their main objective was to estabhsh General Montgomery’s physical presence in Gibraltar. If the Germans beheved that he was there and that he was embarking on a tour of North Africa, they were likely to conclude that an invasion across the Enghsh Channel into France was not planned for the immediate future, for such an undertaking could never be

Scheduled without Monty’s full participation.

By the middle of May there were indications that the Germans were beginning to believe the “Big Lie.” In his report for the week ending May 21, just 16 days before the invasion was to take place, Field Marshal von Rundstedt named southeast England—the area opposite Calais—as one point from which the invasion might be launched.

Allied bombing planes pounded the French coast in the weeks before the invasion. The bombs they dropped were real, of course, but the bombing pattern was meant to mislead the enemy. For every bomb dropped on Normandy, two were dropped on Calais.

Day in and day out this rule was followed religiously. Somewhere, the Allies knew, a German in-telhgence officer was keeping count of the bombs showering down, attempting to establish a pattern to the attacks. His calculations would show that Calais was deemed by Allied bombing planes to be twice as important as Normandy. The Allies hoped the Germans would draw the obvious conclusion.

About a week before the invasion the troops began leaving the sprawling camps where they were quartered. They were brought by trucks to huge assembly areas near the ports from which they were to embark. The assembly areas were called “sausages” because they had an oblong shape with rounded ends.

When the men entered the sausages, they still did not know where they were going to land. They were given photos of the beaches, which had been taken at sea level, and showed the coast exactly as the men

Would see it as their landing craft approached. But there was no indication of where each particular piece of coast was located.

The men were also given maps, but these did not contain any clues as to their destination. The rivers of Normandy had been given Russian names. The city of Caen, about ten miles inland from the coast, was labeled Warsaw.

A few days before the invasion all the planning and secrecy were suddenly placed in jeopardy. A stiff breeze blew through an open window of the British War Office in London and whisked away 12 copies of Top Secret instructions involving the invasion. The sheets of paper drifted down into a crowd of pedestrians on the sidewalk below.

Office workers raced down to the street in a frantic effort to recover the papers. Eleven of the missing sheets were retrieved right away. The twelfth could not be found.

The street was scoured again, then a third time. The missing document remained lost. Officers went through torment believing the worst, that the information would somehow find its way into German hands, wrecking the invasion. Two agonizing hours passed. Then a British sentry, standing duty on the opposite side of the street, turned in the missing sheet of paper. A stranger had handed it to him, he said. No one ever learned the identity of the individual who held the fate of the invasion in his hands.

On D-Day itself, more deceptive tactics were used. Dummy parachutists were dropped to draw German troops from fortified positions or from areas where real parachutists were set to attack.

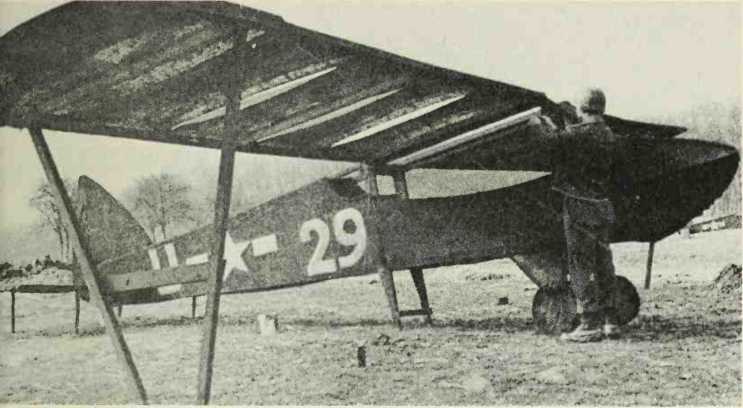

AN AMERICAN SOLDIER PUTS THE FINISHING TOUCHES TO A DUMMY AIRPLANE. (National Archives)

Each dummy was a full-sized representation of a human figure, clothed in an Army uniform. The dummy’s parachute was the real thing.

There were four drops of dummy parachutists on D-Day. One of the biggest of the drops, code named Titanic I, involved 200 dummies. They were dropped near the town of Yvetot about five hours before the first Allied troops were due to hit the nearby beaches. They were meant to draw German defenders away from their beach positions.

To get the Germans to beheve that the drop was the real thing. Allied military experts fitted the dummies with timing devices that triggered recordings of battle noises, sounds of machine gun fire, and exploding grenades. The sounds were so real that anyone in the area would quickly seek cover.

Another part of the deception involved dropping a group of intelligence agents into the area just before the dummy ’chutists were released. The agents put hfe into the attack, firing on German troops or vehicles that entered the area. But they were instructed to allow some enemy soldiers to escape to spread news of the paratroop landing.

Once the invasion began, von Rundstedt reacted just as the Allies had hoped. While German opposition was strong at some points, by nightfall of the first day Alhed forces held several beachheads along the Normandy shore. In the days that followed, no serious counterattack developed.

Wilhelm Keitel, Hitler’s chief of staff, replying to reporters the day after he was sentenced to death as a war criminal at Nuremberg, said this about D-Day: “German military intelhgence knew nothing of the real state of Alhed preparations. Even when craft carrying Allied troops were approaching the coast of Normandy, the highest state of alert was not ordered.”

As late as June 25, almost three weeks after the first landings, von Rundstedt continued to beheve the main Allied assault was targeted on Calais, and he continued to hold back many thousands of troops.

Had they been sent into action, would these German troops have tipped the scales in the first critical hours of D-Day? One can only guess. But one fact is certain. The Big Lie and the Germans’ acceptance of it made the Allied task of gaining a foothold in the Normandy beaches much less difficult and contributed to saving many thousands of lives. For that reason alone, it ranks as one of the war’s important triumphs.

World History

World History