Every month the German Army grew in size and strength. In 1934 the 100,000-man army had had no tanks, no airplanes, and very little artillery, and Germany had been disarmed for fourteen years. But by 1939 Prime Minister Chamberlain was facing a Germany in the process of mobilizing 4 million men. Theoretically, in that four-year period, each of those 100,000 professional soldiers had trained forty men. In fact, not even the German Army could have done that, and only about one man in eight had even the briefest training before mobilization. The Ersatz and Landwehr divisions consisted mostly of middle-aged men who hardly remembered what a rifle looked like. The fact remained that Hitler now had the large army he wanted and was virtually in direct control of its operations.

Poland was a huge parcel of land which had emerged periodically from the mists of European history, but never in exactly the same place. Three times already Poland had been divided between Germany and Russia. Now it was to happen for the fourth time.

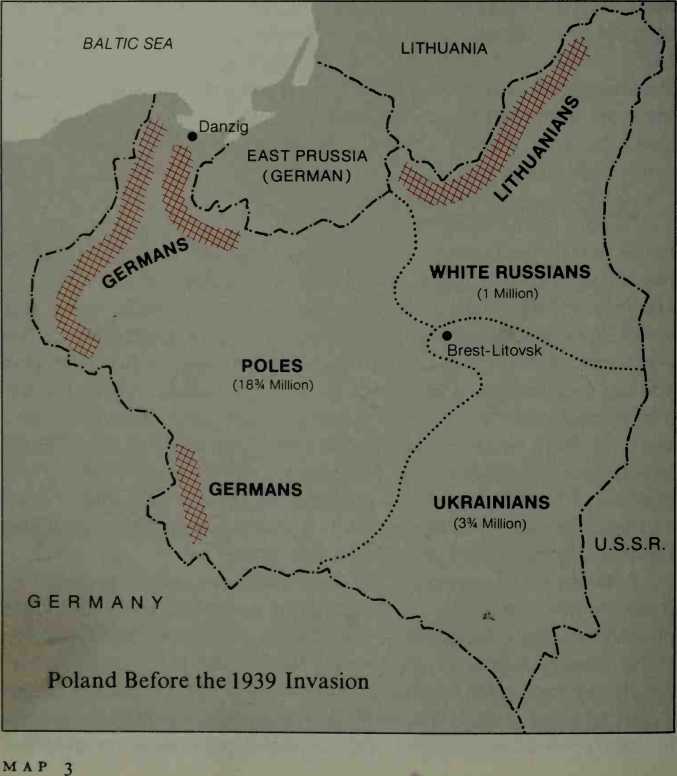

It was inevitable that the frontiers drawn up by Poland at the Treaty of Riga (which followed her victory over the Russian armies in 1920) would be disputed. The northeast region—apart from the border areas taken from Lithuania—was occupied by a million White Russians. The southeast quarter was populated by nearly 4 million Ukrainians. There were a million Germans living inside its western border. The Poles—about 19 million of them—lived in the western half of Poland. Two million Jews were dispersed throughout the land but remained together in communities, principally because of the murderous pogroms against them, which the Polish government did little to discourage.

The Polish government was a combination of soldiers and rightwing politicians. Their conquest of large areas of land from Russia

Had strained the Poles’ relationship with their eastern neighbors, but they were friendly with France and friendly enough with the Nazis to help themselves to a piece of Czechoslovakia when, in 1938, that country succumbed to Hitler’s aggression.

The British and French concessions to him at Munich convinced Hitler that he could screw a few more territorial demands from the men he scoffed at as “old coffee aunties” without much risk of war. He turned his attention next to Danzig.

Poland had been given a “corridor” to the sea, through Prussia, to Danzig, which was now a “free city,” although its population was almost entirely German. Hitler wanted roads and railways across the Corridor and said that Danzig must become German again. By Hitler’s standards, the demands were reasonable. Hitler reckoned that “the worms” who governed the western nations would never go to war for such trifling matters. Hitler told his generals to prepare for an attack on Poland.

But, as might have been expected. Hitler had a trick up his sleeve. This time it had that element of theater that Hitler so loved. Just three days before Hitler first planned to start the attack, the German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact was signed. The Slav “monsters” upon whom all his years of abuse had been heaped were now prepared to divide Poland with him. Hitler reasoned that the news of the pact should be enough to deter the worms. Two days later the British issued a clear warning by signing an Anglo-Polish Mutual Assistance Pact. Hitler remained convinced that the Poles would not go to war and asked them to send a plenipotentiary to Berlin.

The British urged the Poles to negotiate and were confident that they would. The Germans, who were tapping the telephones at the French and British embassies and deciphering the secret telegram messages, shared that confidence. But the Poles would not even name a plenipotentiary. Hitler backed down; now he asked only for the return of Danzig to Germany and for a plebiscite to be held in the Corridor. The Poles still would not agree.

As long before as 3 April, the OKW had ordered the army to prepare plans for an attack on Poland. Commander in Chief of the Army General von Brauchitsch ordered General Franz Haider, Director of Operations for the Army General Staff, to work on them. Haider, a Bavarian artillery officer, ordered his planners to work.12

The Polish plain was a terrain ideally suited for mechanized warfare, even though the roads were very primitive. German intelligence well knew that timing was vital; the rainy weeks of late September and October produce thousands of square miles of mud that would bog down any army. And then there were the broad Polish rivers.

Broad rivers are the most worrying of obstacles to military planners. Even the mighty Vistula upstream from Warsaw was fordable at several places in that summer of 1939. But when the rains started, such broad rivers could become an obstacle that would daunt not only bridge builders but also the men who might have to cross them under fire.

As the diplomatic wrangling went on. Hitler persuaded himself that France and Britain were looking for a way out of their obligations. The Polish invasion was originally set for 26 August but, as X-day approached. Hitler came to believe that he needed a few more days to drive a wedge between the Poles and their Western Allies. And yet with every day that passed, the wet weather that would protect the Poles came closer. Hitler set the date for 1 September, knowing that if the date was again changed, it would mean a delay of some months. Many of the active army divisions had been brought up to full strength by calling in reservists for their “annual training,” while the regular army had been moved to the jumping-off points under the guise of “summer exercises.” But the summer could not last forever.

By now Hitler did not want a Blumenkrieg. He wanted a real war and military victory in Poland, but he did not want France and Britain involved in the conflict. On the night of 28 August Hitler dreamed up a series of demands that he knew would sound reasonable to the Western Allies but be unacceptable to the Poles. These included giving the Poles just one day to get a plenipotentiary to Berlin. Either they would refuse to comply at such short notice or the negotiator would arrive and find agreement impossible. This would enable Hitler to start his attack on 1 September as planned.

With intercepts of the British ambassador’s telephone conversations to London in his hands. Hitler felt sure that this final device would be enough to sever the Poles from the West. At midday on 31 August he gave his army the provisional go-ahead. A few minutes later the Polish ambassador asked to see the German Foreign Minister. At 4 p. M. on that same day, 31 August 1939, with the Polish ambassador still waiting to speak to him. Hitler gave his army the final decision: the attack would begin next morning.

The Polish ambassador told Hitler that the Polish government was now favorably considering the idea of negotiations. But by this time Hitler was determined upon war and intoxicated with his own power. Dissenters were harshly reminded of how the Fiihrer had been right about the Rhineland, Austria, the Sudetenland, and Czechoslovakia. In none of those cases had the worms acted. Hitler had a hatred for Poland that went far beyond any political ambitions. On 22 August he had told his senior commanders of his intention to send his SS units into Poland “to kill without pity or mercy all men, women and children of Polish race or language.” He had told them that he would use his SS to stage a propaganda stunt to start the war.13 And he told them that, after Poland, he would invade Soviet Russia.

Brauchitsch, who had replaced Fritsch as army Commander in Chief, did little or nothing to dissuade Hitler from aggression. When Hjalmar Schacht, former Minister of Economics and Reichsbank president, reminded Brauchitsch that his oath to the Constitution required that a declaration of war needed the approval of the Reichstag, Brauchitsch told him that if he tried to enter the Army High Command (now moved to Zossen, outside Berlin) he would have him arrested.

In the early hours of 1 September the German invasion began. For what seemed like an age, the British government hesitated as radio reports told of the Polish fighting. Hitler remained in Berlin, still clinging to the hope that Britain and France would find a way to avoid allying themselves to a country that was already doomed. But on 3 September Britain went to war and some hours later France did too. Hitler shrugged, got into his private train, Amerika, and traveled up to the front.

The planning for that attack had been going on all through the summer. The planning team was called Arbeitsstab Rundstedt after its leading figure, Generaloberst Gerd von Rundstedt. Sixty-four years old, Rundstedt had once been the army’s senior general after Blomberg and Fritsch. But for his age, he would have been made Commander in Chief of the Army, according to what Hitler told Keitel. Rundstedt was an eccentric. He seldom wore a general’s uniform (or later a field marshal’s), preferring that of Infantry Regiment No. 18, of which he was honorary commander. Because of his insignia he was often mistaken for a colonel and addressed as such, but he found that amusing. Recalled from retirement, he refused to purchase an overcoat on the grounds that he was too old to make the cost worthwhile. He was an avid reader of detective stories but self-conscious enough to read them in the open drawer of his desk so that they could be quickly hidden from sight.

Although in charge of the planning for the attack on Poland, Rundstedt remained in his house in Kassel through the summer and left the work to the two officers assigned to him. One of them was Erich von Manstein, who had spent almost his entire career in staff work, although at this time he was commanding the 18th Infantry Division at Liegnitz. Fifty-two years old, a stern-looking man with a large beaky nose and heavy eyebrows, Manstein had been chief of the operations branch of the General Staff and later its deputy chief. He had lost his job when, after Blomberg’s resignation, senior officers with little liking for the Nazis had been moved to less sensitive positions. Guderian called Manstein “our finest operational brain,” and more than one historian has called him the most skillful general of the war.

Manstein’s participation in the planning has tended to obscure the contribution made by Colonel Gunther von Blumentritt, who was at that time an officer on the General Staff as chief of the training section. The work these two men did is more remarkable considering that the army would not give them time off in which to do it. Both men, separated by many miles, continued with their day-to-day duties.

As the plan evolved, Rundstedt was ordered to take command of the southern group of armies for the attack and Manstein was made his chief of staff. Army Group North was formed from the existing Army Group Command I under General Fedor von Bock.

Manstein and Blumentritt were two of a small number of officers whose experience with the General Staff and as chiefs of staff to senior commanders made them preeminent in the skills of planning and gave them an importance beyond their military ranks. Other such officers included General Gustav von Wietersheim, who was to command the motorized units that followed Guderian in May 1940, and Haider, who was to oppose Manstein’s ideas.

World History

World History