During the War of 1812, the stringent British blockade had kept American ports crowded with idle shipping while cotton, grain, tobacco, and other products piled high in warehouses and on wharves. On the ratification of the Treaty of Ghent, American ships loaded with goods took to sea. At the same time sorely needed foreign goods began to arrive from England, continental Europe, the West Indies, India, and China. This was only the beginning of an unprecedented surge in American overseas commerce which, between 1815 and i860, nearly quintupled in value.

The U. S. Navy was not permitted to decline, as had happened after earlier wars. This was partly because of the need to protect expanding trade and partly because of American pride in the Navy’s accomplishments. Three ships of the line, the Independence, the Franklin, and the Washington, laid down during hostilities, were completed shortly after the return of peace. By 1818 eight more had been laid down, but three of these ships were never completed. In 1822 work was begun on the mighty 120-gun Pennsylvania, the largest sailing ship ever built for the U. S. Navy, and the largest in the world at the time of her launching in 1837. During the same period numerous frigates, sloops, and schooners were also added to what soon became a respectable oceangoing fleet. As American trade continued to expand, segments of the fleet were formed into semipermanent squadrons and dispatched to the four quarters of the world, wherever they were needed.

The first of the squadrons to be formed was actually a revival of the Mediterranean Squadron of the Tripolitan

War period. Its objective was the same, to deal with the nuisance of Barbary pirates. The Dey of Algiers, complaining that the U. S. tribute money was not being promptly or fully paid, had begun in 1807 to seize American merchantmen. In 1812 the United States had broken off diplomatic relations with the dey’s government. Shortly after the conclusion of peace with England, Congress declared war on Algiers, and in May 1815 Commodore Stephen Decatur sailed for the Mediterranean Sea with a force of nine vessels, including three frigates. In the Mediterranean, Decatur’s squadron captured two Algerian warships, then proceeded to Algiers. There Decatur presented his terms: no further tribute, no more capturing of American ships, and a treaty to be concluded giving most-favored-nation status to the United States. When the dey hesitated to abandon his piratical practices, Decatur threatened to capture the rest of his squadron, expected soon in port. At that the dey reluctantly signed. “Why,” he complained, “do they send wild young men to treat for peace with old powers?”

Decatur next proceeded to Tunis and Tripoli, where he demanded and received indemnity for American privateer prizes which, when sent into these ports during the War of 1812, had been turned over to the British. The United States, in order to impress upon the Barbary Powers its ability to maintain its rights, sent after Decatur’s squadron a more powerful one which, included the new 74-gun ship of the line Independence, commanded by Commodore William Bainbridge. This squadron touched at the same ports.

The growing U. S. Navy and the expanding American fleet operations posed severe administrative problems, particularly since no clear distinction was drawn between operational and logistic control. Moreover, both were administered by an inexperienced Secretary of the Navy, who had no ofiBcers specifically assigned to advise him. To alleviate this situation. Secretary Benjamin Crowninshield in 1815 persuaded Congress to create a Board of Navy Commissioners, consisting of three senior captains, to administer logistics and to advise the Secretary on operations and policy. Early members of the board were Captains Porter, Decatur, and Bain-bridge. In 1842, in response to increasing complications incident to the introduction of iron construction and steam propulsion, the board was replaced by five bureaus, each headed by an oflBcer: Yards and Docks; Ordnance and Hydrography; Construction, Equipment and Repair; Provisions and Clothing; and Medicine and Surgery.

No comparative evolution occurred to establish professional control of naval operations, mainly because senior naval ofiBcers and national administrations, counting on the nation's geographical isolation and misreading the lessons of the American Revolution and the War of 1812, remained defense-minded. The Navy’s main function, they believed, was the protection of maritime commerce. Its secondary function was defense against enemy invasion of coastal waters—though actual coast defense was assigned chiefly to extensive new Army-controlled coastal fortifications. OfiFensive naval operations were to be limited to raiding enemy commerce, for which privateers also were to be used, and attacking separated segments of a hostile fleet. With such limited concepts of the function of American sea power. Congress maintained naval appropriations at an average of $7 million annually, less than a quarter of British or French appropriations.

SUPPRESSING PIRACY IN THE WEST INDIES

The West Indies Squadron was established to safeguard shipping and to track down sea robbers in another hotbed of piracy. When the European naval powers became preoccupied with the Wars of the French Revolution and Empire, buccaneering, long suppressed, began again to flourish in the Caribbean Sea and the Culf of Mexico. It was given a special impetus after 1810, when Mexico, Venezuela, and Colombia revolted against Spanish rule, sending out swarms of privateers who readily turned to piracy. Cuba and

Puerto Rico, remaining loyal to Spain, sent out retaliatory privateers with an equal taste for marauding.

The most notorious freebooter of the period was, however, an erstwhile New Orleans master blacksmith, Jean Lafitte, who took to smuggling, then to piracy, and finally commanded a pirate fleet from an island base near the mouth of the Mississippi River. Offered a naval captaincy by the British as an inducement to assist in the attack on New Orleans, Lafitte informed American authorities of the British plan. He and his pirate gang then joined General Jackson in the successful defense of the city. President Madison rewarded the pirates with pardons, which they gratefully accepted, but they promptly resumed their profitable vocation.

With end of the war in Europe and North America, trade in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea flourished as never before. Because of heavy westward migration. New Orleans developed a maritime commerce second among American ports only to that of New York. The pirates fell greedily upon this commerce, attacking hundreds of merchantmen each year.

The savagery of some of the attacks is well illustrated by the case of the merchant sloop Blessing, which was halted by a pirate schooner south of Cuba. When the master of the Blessing, William Smith, failed to produce a satisfactory sum of money, the pirate captain had him thrown overboard and fired at him with a musket until he sank. The pirate then turned on Smith's screaming fourteen-year-old son, clubbed him in the head with the butt of his musket, and threw him overboard too. Finally, stripping the Blessing of everything of value, the pirates set fire to her and set her crew adrift in a boat.

The American government assigned to the Navy not only the job of suppressing the pirates but also the more delicate task of dealing with the Latin-American colonies from which most of the pirates came. Thus in 1819 the Secretary of the Navy sent Captain Oliver Hazard Perry on a special mission to Angostura (now Ciudad Bolivar, Venezuela) to dissuade General Sim6n Bolivar from issuing blank letters of marque that were in efiFect mere licenses to piracy. Perry had a successful interview with the Vice-President of the Colombian Republic, the general being absent from the capital; but the mission cost him his life, for he caught yellow fever and died on the return voyage.

As piracy originating from the new republics subsided, thanks to the Perry mission, the problem became intensified in the vicinity of Cuba and Puerto Rico. The Spanish authorities on these islands, resenting U. S. aid to their revolted colonies, tolerated the outrageous marauding expeditions that operated from

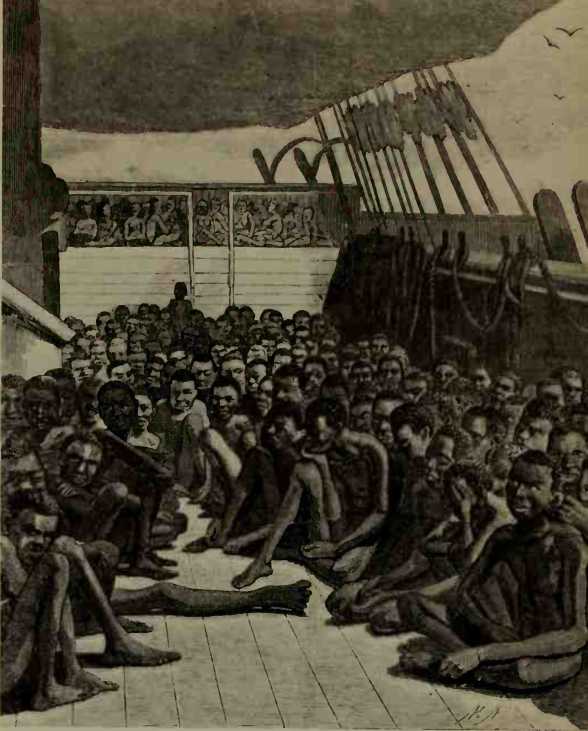

Aboard a slaver.

Their shores. Many of the pirates were in fact financed by leading Cuban and Puerto Rican citizens, who shared in the profits.

It was to deal with this maritime lawlessness that the Navy Department created the West Indies Squadron, first commanded by Captain James Biddle in the captured frigate Macedonian. Occasionally the heavy ships overtook a pirate craft at sea, but much of the pursuit was done in open boats, which navigated in shallow inlets and lagoons. The chase often ended in hand-to-hand fighting ashore. More dangerous than pirate weapons in this toilsome tropical service was yellow fever. Of flagship Macedonians crew of about 300, a third died of fever the first summer.

Captain David Porter, Biddle’s successor as commodore of the squadron, sought the cooperation of the Puerto Rican governor, but with scant success. An American schooner taking a message into San’Juan was fired on from guns ashore which killed her commanding oflBcer. A lieutenant sent to Fajardo on the Puerto Rican east coast to inquire about stolen American goods was thrown into jail. For the hot-tempered Porter this latter act was too much. Landing 290 armed men, he vowed that he would have an apology from the mayor or else blow Fajardo off the map. Porter promptly received his apology but was called home to face a court-martial, which suspended him for six months for exceeding his authority. He thereupon resigned his commission in the U. S. Navy. Ceneral Jackson denounced the court-martial, praising Porter for upholding the honor of the flag. Upon becoming President, Jackson appointed him Minister to Turkey, where he died in 1843.

Meanwhile Captain Lewis Warrington, successor to Porter as commodore of the West Indies Squadron, had completed the work of his predecessors. The Americans, operating sometimes jointly with British pirate hunters, gradually made the Caribbean safe for commerce. By 1829 the American squadron was reduced to a small patrol force. The U. S. Navy had captured, in all, about 65 pirate vessels.

THE NAVY AROUND THE WORLD

Although participation of Americans in the African slave trade had been outlawed in 1807, and although the United States and Britain had agreed in the Treaty of Ghent to cooperate in suppressing it, many privateer veterans of the War of 1812 entered the traffic, continuing even after Congress in 1819 branded it piracy. In 1820 the corvette Cyane, first of several American warships sent to cruise the African west coast, captured nine slavers. Her successors did less well, partly because they were much involved in founding and protecting the Republic of Liberia, populated mostly by freed American slaves. In 1824 the United States withdrew its patrol in a dispute with the British over rights of visit and search, a subject about which Americans were understandably sensitive. Thereafter for many years, slavers of several nations made use of false U. S. identification to foil the British patrols. In the Webster-Ash-burton Treaty of 1842, the United States again agreed to cooperate with the British, this time by maintaining an 80-gun Africa Squadron. Although the squadron operated regularly until after the outbreak of the Civil War, the slave trade continued almost unabated, American ships and capital participating in it.

Of the several scientific expeditions sponsored by the U. S. Navy before the Civil War, none attracted more favorable interest or was more fruitful than the six-ship United States Exploring Expedition of 1838-42. This squadron was commanded by Lieutenant Charles Wilkes and included a group of scientists with elaborate equipment. They discovered and explored the coast of Antarctica, visited the Tuamotu, Society, and Fiji

Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry.

Islands, surveyed portions of the west coast of North America, and brought home a wealth of oceanographic and geographic data.

After the Peace of Ghent, American commerce with the Far East not only revived but soon reached boom dimensions. The perils of such distant trade were demonstrated when in 1831 the Salem pepper trader Friendship was plundered and part of her crew slaughtered at Quallah Battoo, Sumatra. The following year U. S. frigate Potomac arrived at Quallah Battoo to take punitive measures. Her sailors and marines, with gunfire support from the ship, captured and burned the town. The natives were granted peace only upon guaranteeing safety for Americans who should visit the area thereafter.

As a more sweeping guarantee, the Navy in 1835 established a permanent East India Squadron. Commodore Lawrence Kearny, its commander from 1840 to 1842, so favorably impressed the Chinese government by his firmness, fairness, and tact that he was able to pave the way for a general opening of China to American trade. When the expanding United States reached the Pacific coast, a transpacific steamship line to China was planned.

Squarely in the way of this line stood the still medieval Empire of Japan, which for nearly three centuries had avoided contact with foreigners, the sole exceptions being the Chinese and the Dutch, who were allowed highly restricted trading privileges through the port of Nagasaki. Shipwreck victims landing on the Japanese coast were treated as felons. The United States, with its flourishing Oriental trade and growing Pacific whaling fishery, was anxious to change all this—to open in Japan ports of fuel and refuge and hopefully also of trade. But American attempts to establish diplomatic relations with Japan were insultingly rebuffed. In the early 1850s President Fillmore sent an impressive naval expedition to try once again to negotiate some sort of treaty.

Selected as commodore of the Japan Expedition was Captain Matthew Calbraith Perry, brother of the victor of Lake Erie. The choice was an apt one. “Old Bruin” Perry at age fifty-nine was able, iron-willed, imperious, not to say pompous; he was just the man to impress the ceremonious, rank-conscious dignitaries of Japan. Perry prepared the expedition with the utmost care, learning all he could about the Japanese, seeking out top-notch officers and crews, and collecting as gifts striking examples of Western technology.

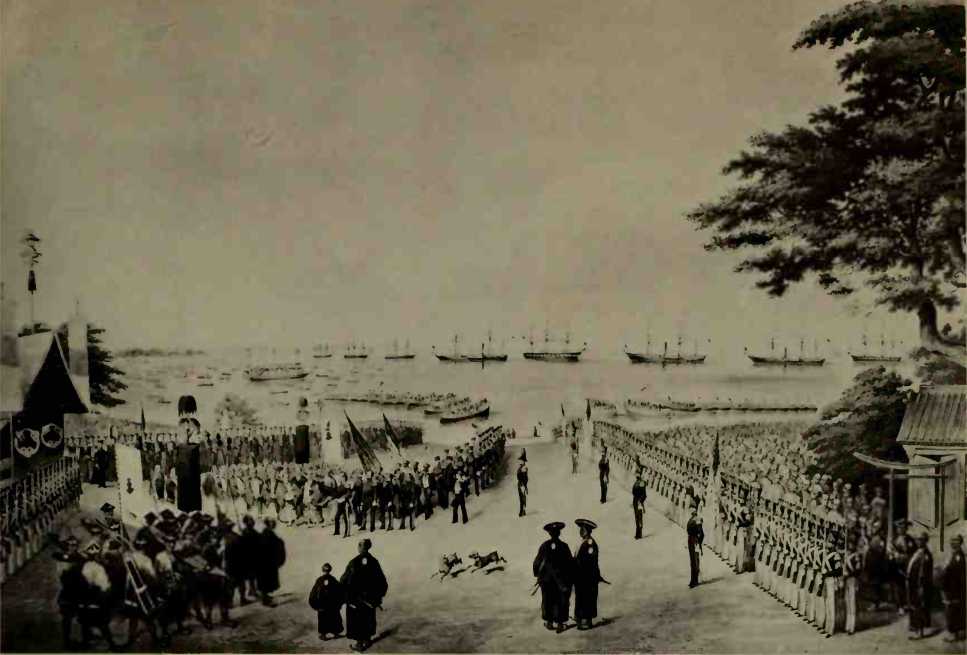

The Japan Expedition entered Tokyo Bay on July 8, 1853, the sidewheelers Susquehanna and Mississippi towing the sailing sloops Plymouth and Saratoga. Perry, styling himself “Commander in Chief United States Naval Forces Stationed in the East India, China and Japan Seas,” rejected peremptory orders to depart and refused to make himself available to minor dignitaries who arrived aboard his flagship. These were met by junior officers, who announced that the commodore had come to deliver a letter from his president to oflBcials of suitable eminence representing the emperor.

The ruling shogunate, lacking weapons to expel Perry by force and impressed by his dignified conduct and assertion of rank, decided that they could get rid of him only by meeting his demands. They therefore had a reception hall built on the shore in record time and dispatched thither two princes in gorgeous array attended by 5,000 soldiers. Commodore Perry now came ashore in stately procession, to the sound of gunfire salutes and ships’ bands playing “Hail, Columbia!” The princes, in dignified silence, received the presidential letter enclosed in a rosewood box. Perry then departed

Perry delivers the President’s letter.

To winter in Chinese waters, announcing that he would return the following year for the imperial reply.

When he returned to Tokyo Bay the following February with an augmented squadron, the shogunate had already come to the conclusion that Japan’s only hope for peace lay in making some concessions. After lengthy negotiations in another specially built reception hall, the Japanese representatives concluded with Perry the Treaty of Kanagawa, opening two ports to American shipping but granting no trade. Now at last the Japanese dropped their reserve. Many insisted upon riding, their robes flapping in the breeze, atop the coach of a miniature steam railway, one of Perry’s gifts. At a subsequent banquet aboard Perry’s flagship, one of the imperial secretaries, flushed with drink and enthusiasm, threw his arms about the startled commodore’s neck, exclaiming, “Nippon and America, all the same heart!”

Four years later the shogunate, realizing that Japan must have foreign trade to promote the technological revolution she needed to achieve security in the modern world, opened commercial relations with the United States.

PATHFINDER OF THE SEAS

While most naval ofiicers were distinguishing themselves as explorers, diplomats, protectors of trade, and chasers of pirates and slavers. Lieutenant Matthew Fontaine Maury usn was diligently studying the seas for ways to improve navigation.

Shorebound by a crippling accident, Maury was appointed in 1842 to the usually humdrum post of superintendent of the Depot of Charts and Instruments in Washington, D. C. Under his vigorous superintendency the operations of the depot soon ceased to be humdrum. Noting that the charts he issued were British and nearly all long out of date, Maury and his midshipman

Assistants began to examine the log books of U. S. naval vessels deposited at the depot. From the logs they extracted data concerning prevailing winds and ocean currents, weather conditions, length of daily runs, and seasonal variations.

Maury became convinced that navigators often fought the forces of nature instead of using them. He was certain that, by taking account of winds and currents and avoiding storms and calms, mariners could greatly diminish hazards and speed up voyages. To extend and confirm his investigations, Maury prepared an abstract log which he sent to ship captains, requesting that in the spaces provided they record navigational, hydrographic, and meteorological observations and return the completed logs to him. At his request the Secretary of the Navy made such reports mandatory for cruising U. S. naval vessels. With this aid, Maury devised wind and current charts and determined the most eflB-cient sea routes from point to point. "

Widespread skepticism of Maury’s findings was dispelled in 1849 when a Baltimore merchant skipper, following his suggested routes, cut 35 days from the usual time required for a voyage to Rio de Janeiro and back. Thereafter Maury’s charts and their accompanying Explanations and Sailing Directions were eagerly sought, particularly by clippers which, in response to the gold rush, were plying in even greater numbers between New York and San Francisco. The use of Maury’s charts and directions shortened the clippers’ average sailing time from 187 to 136 days.

In recognition of his achievements, Maury was appointed superintendent of the new United States Naval Observatory, which absorbed the Depot of Charts and Instruments. Despite broadened responsibilities, Maury continued his maritime charting and pathfinding. New charts showed the best whaling grounds, the extent of iceberg drift, and water temperatures from season to season. Successive editions of the Explanations and Sailing Directions expanded from 10 to 1,300 pages.

Maiuy’s charting of separate east - and westbound transatlantic steamship lanes, when generally adopted, practically eliminated the numerous collisions that were costing ships and lives; his charts and routes saved shippers in many countries uncounted millions of dollars. His book Physical Geography of the Sea virtually founded the science of oceanography, and his soundings and studies of the ocean depths paved the way for the laying of the Atlantic telegraphic cable.

In 1853, in response to a proposal by Maury, representatives of the major maritime nations held in Brussels the first International Maritime Meteorological Conference. On their unanimous recommendation Maury’s system of observing, reporting, recording, and analyzing maritime phenomena was adopted on a worldwide scale.

THE TECHNOLOGICAL REVOLUTION

The United States was a major participant in the 1815-60 technological revolution that transformed the world’s navies as they shifted from sail to steam, from wood to iron, and from shot to shell. In the process the major fleets, while not changing greatly in appearance, altered more in operational characteristics than they had done in the preceding three centuries.

When the British blockade closed dowm American commerce in the War of 1812, the U. S. Navy turned to Robert Fulton, the maritime engineering genius. Since 1807 Fulton had been operating on the Hudson River his commercially successful steamer Clermont, propelled by paddle wheels of his own invention. Could he devise a harbor defense vessel and blockade breaker powerful enough to deal with ships of the Royal Navy?

Fulton could and did. His efforts produced the Demologos, the first steam-propelled warship. She had twin hulls, joined above the water in catamaran fashion, and carried a paddle wheel in a channelway between the hulls. Her engines and her twenty 32-pounder guns were protected by five-foot-thick timbers, armor which no ordnance of the day could penetrate. Had she got into action, the Demologos would surely have caused among the British blockaders an alarm as frenzied as that later produced among the Union blockaders by the appearance of U. S.S. Merrimack. Her attack would have been far more decisive than that of the Merrimack, for she was invulnerable to anything the British could have sent against her, and her inevitable victories would probably have ushered in the naval age of steam without delay.

But before the Demologos, launched in the fall of 1814, was ready for action, the war had ended. Renamed the Fulton after the death of her designer, she saw brief peacetime service and then was tied up as a receiving ship in the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

In the next two decades business interests built him-dreds of steamers, which took over most of the passenger and carrying trade in America’s inland waterways. The Navy built no steam warships, although in the 1820s Commodore Porter made good use of a converted commercial sidewheeler, the Sea Gull, in chasing pirates in the West Indies. There were excellent reasons for the Navy’s delay. Fuel and machinery took up space.

Trial run off New York of U. S.S. Fulton (formerly Demologos), the first steam-propelled warship.

Which was at a premium in a man-of-war. The early, low-pressure steam engines were notoriously unreliable, and were such heavy consumers of fuel that they afforded a maximum cruising radius of only about loo miles. The paddle wheels would cover a large part of a warship’s broadside, cutting deeply into her firepower; moreover, sidewheels and machinery were highly vulnerable to shot. In battle a single hit could leave a steamer both outgunned and fatally outmaneuvered. Hence naval officers everywhere preferred to wait until commerical vessels had evolved a dependable, fuel-conserving engine, and until bigger guns were developed to offset the loss of broadside area.

Matthew Galbraith Perry, as a young officer, had seen the Demologos launched, and as captain of a ship in the West Indies Squadron he had observed the versatility of the Sea Gull. His interest aroused, he kept himself informed of progress in steam engines and boilers. In the 1830s, when he was commandant of the Brooklyn Navy Yard, he concluded that the time had come for the U. S. Navy to take the plunge. He accordingly prevailed upon Navy Secretary Mahlon Dickerson to let him build a prototype steam warship.

The result was the Fulton II, constructed imder Perry’s supervision, and launched in 1837. Perry himself took command of her, in addition to his duties as navy yard commandant. A 700-ton, i8o-foot-long sidewheeler, she was more conventional than the first Fulton, and much faster. She was awkward and barely seaworthy, but she taught Perry and the Navy what to avoid in later steamships. Equally important, she convinced Congressional skeptics that a steam navy was practical.

On Perry’s recommendation. Congress appropriated funds for the steam warships Mississippi and Missouri, launched in 1841. These fine vessels, nearly 1,700 tons each, and 229 feet long, were the dreadnoughts of their day, giving the United States a temporary lead over all the other navies of the world. The Missouri was destroyed by fire in 1843, but the Mississippi had a distinguished career. She served under Perry in the Mexican War and the Japan Expedition, and during the

Civil War she played an important part in reopening the river whose name she bore.

Most of the Navy’s remaining objections to steam-driven warships were overcome by the invention of a practical screw propeller. Both screw and engine were beneath the waterline, not easily reached by shot, and no broadside area was masked. Captain Robert F. Stockton usN persuaded the nautical screw’s chief designer, the Swedish inventive genius John Ericsson, to come to the United States. Here Ericsson designed, and Stockton supervised, the construction of the steam sloop Princeton, the first screw-driven warship.

In 1855 the Merrimack was launched; she was the first of a series of fast screw frigates acquired by the U. S. Navy. These frigates were wooden-hulled vessels and, like all large steamers of the day, were provided with masts and sails. In appearance they rather closely resembled the frigates of the War of 1812. '

In the pre-Civil War period, Britain and France made increasing use of iron for ship armor, and later also for hulls—partly to offset the growing power of gunfire and partly because they were running out of ship timber. The United States, which had ample timber, continued to build the cheaper wooden ships, both naval and commercial. For several years the speedy American sailing clippers competed favorably with European steamers, but by i860 the steam-driven iron vessels had developed to a point where they clearly outclassed wooden vessels propelled by steam or sail.

Because paddle wheels masked so much of the broadsides of early steam warships, experimenters sought means of securing greater firepower with fewer guns. The pivot gun, which could be swung about to strengthen either broadside, was one obvious answer, but the main trend was toward bigger guns. This necessarily meant stronger guns, for charges needed to propel shot weighing much more than 32 pounds were likely to burst the old cast-iron ordnance, killing or injuring the gun crews.

Ericsson, by shifting to wrought iron, was able to build a practical 12-inch gun, the Oregon, which he mounted in the Princeton. A poor imitation of the Oregon, designed by Captain Stockton and also mounted in the Princeton, shattered during an exhibition firing, killing an oflficer, two congressmen, the Secretary of the Navy, and the Secretary of State. This accident put an end to experiments with wrought-iron ordnance for some time. Commander John A. Dahlgren usn developed a highly practical bottle-shaped gun, thick in proportion to pressures in the barrel. The Dahlgren gun was used widely by the Navy in the Civil War.

Naval officers had preferred solid shot 'for use against enemy ships until 1853, when the Russian fleet opened the Crimean War by sinking seven Turkish frigates with shellfire. That demonstration converted most navies to the use of shell for attack and iron armor for defense.

The Civil War navies used both solid shot and shell, wooden ships and ironclads. Their shells were iron spheres filled with explosive and fitted with time fuses. The shell was held in place inside the gun barrel by a round grommet, or collar; the flash of the exploding charge, passing around the shell, ignited the outwardpointing fuse.

In 1859 the British adopted the built-up rifled Armstrong gun that fired an elongated percussion-fused shell at long range with great accuracy.® The Americans, however, stuck to their Dahlgrens. At this stage of development, and at the close ranges the Americans favored, these guns were found better for penetrating armor.

THE UNITED STATES NAVAL ACADEMY

The British navy had had a naval academy for the education of its young officers since 1733. In 1802 the U. S. Army had acquired its military academy at West Point. But the U. S. Navy had nothing of the sort during the first half century of its existence. American midshipmen were expected, for the most part, to “learn by doing.” Chaplains were indeed ordered to instruct them in mathematics, navigation, and French, but they were rarely qualified to do so. Ships of the line each had an underpaid, politically appointed schoolmaster. Classes afloat were, however, not taken very seriously and were subject to constant interruption as midshipmen were ordered to “more important duties.”

American naval officers, if they were educated at all, were thus likely to be self-educated. Two of the most successful of the self-educated officers, Matthew Fontaine Maury and Matthew Calbraith Perry, strongly advocated the establishment of an academy ashore for training midshipmen. But Congress refused to authorize the necessary appropriations, especially as many naval officers insisted that a midshipman could learn all he needed to know by “keeping his eyes open,” and that training midshipmen ashore would be like “trying to teach ducks to swim in a garret.”

As it became increasingly evident that midshipmen

® The most common form of built-up gun has a barrel consisting of two or more tight-fitting concentric cylinders.

Could not leam enough while afloat to pass their required examinations, coaching schools were established in the Boston, New York, and Norfolk navy yards, and at the Naval Asylum, a home for old sailors in Philadelphia. In these schools the midshipmen were trained by both civilian and military professors and then examined for promotion by a board of senior naval ofificers.

The Philadelphia school began to eclipse the others in reputation in 1842 when twenty-three-year-old William Chauvenet succeeded to the head of its small faculty. Brilliant, energetic, a recent honor graduate of Yale, Chauvenet set out to develop a two-year course at the Asylum School, but did not succeed because senior officers said that midshipmen could not be spared so long. He did, however, establish a one-year course, maintaining such high standards that the Navy Department began to phase out the other schools and send all midshipman trainees to Chauvenet at Philadelphia.

It is not clear when Chauvenet and Ceorge Bancroft, the historian and educator, first got their heads together, but when Bancroft became Secretary of the Navy in 1845, and Chauvenet were in agreement that the time was ripe for establishing a college of the Navy.

The idea may have been Chauvenet’s, but Secretary Bancroft had the finesse to see it through.

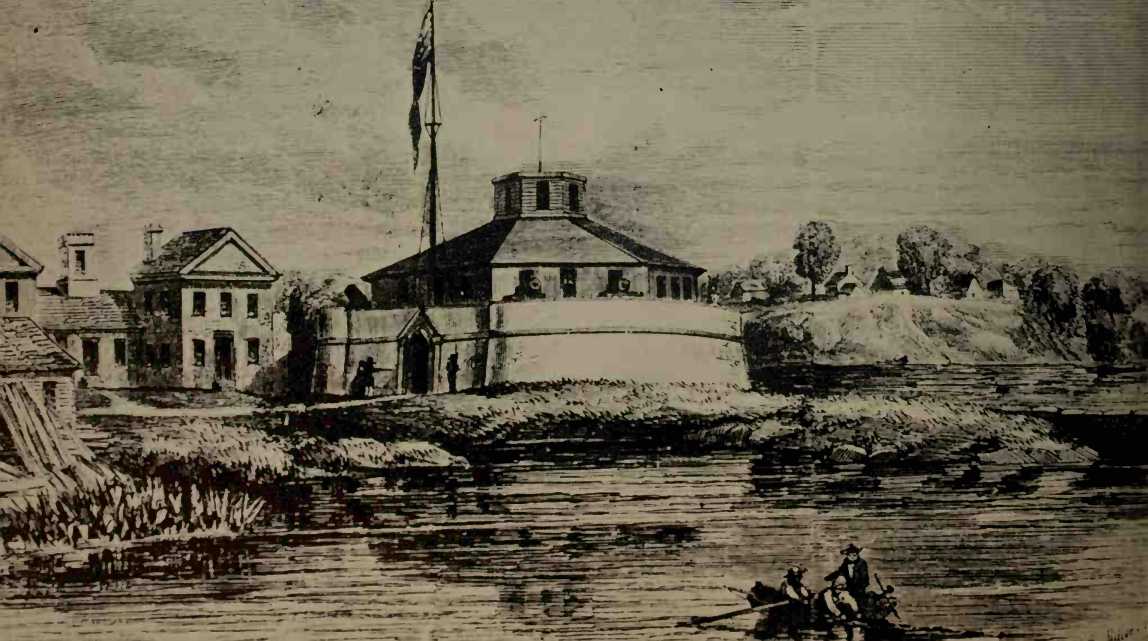

Bancroft first induced the Army to transfer to the Navy an outdated post, old Fort Severn at Annapolis, Maryland. Then, when the examining board of senior officers, including Commodore Perry, met at Philadelphia in 1845, Bancroft consulted them. He recommended moving the school to a better location and proposed Annapolis. The officers. concurred on both points.

The new Naval School opened at Annapolis on October 10, 1845, under the stem but fair superintendency of Commander Franklin Buchanan. Although both faculty and student body had been enlarged, it was generally assumed that this was merely the Philadelphia school transferred to Annapolis in order to remove the midshipmen from the temptations of the big city.

The school was at first, like its predecessors, a mere coaching center, with midshipmen attending on uncertain schedules between voyages. So it remained in 1846 when Bancroft left the Navy to become Minister to Great Britain, and so it remained the following year when Buchanan departed to fight in the Mexican War. Chauvenet, left behind as president of the school’s academic

The United States Naval Academy in 1853. The wooden structure atop old Fort Severn (center) was a gymnasium.

THE MEXICAN WAR, 1846-1848

Board, supervised the development of the long-range plan which would carry out the intention of its founders. In 1850 the plan was adopted. The school was renamed the United States Naval Academy and its course of instruction was extended to four years.

THE MEXICAN WAR,

1846-1848

By 1845 the chronically unstable Mexican government had almost lost control of California; Texas had been independent of Mexico for nine years. At the request of the Texans, Congress voted to annex their coimtry. Early in 1846, Ceneral Zachary Taylor marched 4,000 U. S. Army troops to the Rio Crande, over territory that Mexico had never recognized as a part of Texas. Thereupon Mexican troops crossed the river, attacked Taylor’s army, and were repulsed. The United States then declared war. Taylor, supported by the U. S. Gulf Squadron, now crossed the Rio Grande, captured the town of Matamoros on the Gulf coast, and plunged inland.

Meanwhile, the U. S. Pacific Squadron, a frigate and three sloops, was operating on the coast of California. Under the command of Commodore John Sloat, parties from the squadron went ashore at Monterey and San Francisco, where they raised the U. S. flag without opposition. Sloat then fell ill and was relieved by Commodore Robert Stockton, who had arrived in the frigate Congress.

Marines and sailors from Stockton’s squadron now joined American forces ashore. These land forces consisted of 160 scouts, frontiersmen, and California settlers led by Captain John C. Fremont, and 100 U. S. Army troops that Brigadier General Stephen W. Kearny had led across country from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Operating sometimes together and sometimes apart, these small forces captured Los Angeles, San Diego, Santa Barbara, and other California settlements. The Treaty of Cahuenga, signed early in 1847 between the Americans and the leaders of the weak Mexican defense force, gave California to the United States. Kearny’s army force had already annexed the territory between California and Texas. Thus, since the Americans and British had now settled their dispute over the Oregon Territory, continental United States was complete except for the later purchases of Alaska and the Gadsden Tract.

The United States, having brought the misgoverned settlers of the Southwest under the protection of the American flag, had won its war. Unfortunately, however, the Mexican government did not recognize the American victory, even though General Taylor’s army was penetrating ever deeper into northeastern Mexico while the Gulf Squadron maintained a close blockade of her east coast. To convince the Mexicans that they were defeated, President Polk decided to use the classical con-vincer, capture of their capital. He therefore ordered Lieutenant General Winfield Scott to land an army at Veracruz and march on Mexico City. The task of getting Scott’s 14,000 troops ashore required the full support of the Gulf Squadron, commanded at that time by Commodore David Conner.

On March 4, 1847, U. S. Army transports joined Conner’s squadron in the roadstead of Anton Lazardo, 13 miles southeast of Veracruz. Assembled in the roadstead were nearly 100 ships, including a fair number of steamers. It was the largest amphibious operation undertaken by the U. S. Navy before the North African invasion in World War II. General Scott and Commodore Conner reconnoitered the shoreline in a small steamer and selected for the landing place a stretch of beach three miles south of Veracruz.

The landing on March 9, though conducted without rehearsal, was a model of efficiency, resembling some of the smoother amphibious assaults of World War II. Off the beachhead, frigates and sloops at a distance and a line of gunboats close in, prepared to lend gunfire support. The troops went ashore in waves of surf boats, each commanded by a midshipman or petty officer and rowed by seamen. Mexican cavalry appeared briefly behind the beach, but, observing the firepower the Americans could bring to bear, they prudently retired inside the city defenses. Hence the soldiers landed to the music of ships’ bands rather than the roar of gunfire.

Commodore Perry, who soon relieved the ailing Conner as commander of the squadron, arranged with General Scott for joint operations against Veracruz. After a two-day bombardment by navy guns afloat and army and navy guns ashore, the city capitulated. Scott’s army now marched inland toward Mexico City, while Perry’s squadron maintained the blockade and took possession of ports. The Americans permitted exports and nonmilitary imports but collected customs duties to help pay for the war.

The two U. S. armies in Mexico were consistently victorious over their ill-equipped adversaries. Scott’s army entered the Mexican capital in mid-September, but no Mexican authority could be found that dared to take responsibility for ceding the territories that U. S. forces had already annexed. At length, after prolonged negotiations, peace was restored in early 1848 by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

World History

World History