Would have been much better employed in North Africa, a theatre which, as a result of the Russian campaign, was inevitably down-graded in Hitler’s eyes, with serious consequences for Italy.

The resultant withdrawal to the Balkans of the bulk of the German air force units which Hitler had sent to Sicily at the end of 1940 greatly reduced the pressure upon Malta, the British island base which lay athwart the main supply route from Italy to North Africa. In the autumn of 1941, as a result, Italian convoy losses increased to an intolerable degree. So, on 2nd December, Hitler issued a directive appointing Field-Marshal Albert Kesselring as Commander-in-Chief South, in charge of an entire air corps and with the threefold mission of protecting the supply route between Italy and North Africa, co-operating with the Italo-German ground forces in North Africa, and stopping enemy traffic through the Mediterranean. Kesselring’s appointment, which was regarded with mixed feelings by the Italians, marked a further stage in the subordination of Italy to Germany.

Not long after Kesselring’s arrival in Italy, the Second World War was transformed into, a truly global conflict by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour and British and Dutch possessions in the Far East. Mussolini, together with Hitler, gratuitously linked his fate with that of the Land of the Rising Sun by declaring war upon the USA on 11th December 1941. Initially American intervention did not provide much relief for the British position in the Mediterranean and the Middle East, whereas Japanese intervention seemed to offer alluring prospects to the Axis powers. 'The Japanese admirals have informed us that they intend to proceed towards India,’ Ciano noted in his diary on 7th March 1942. 'The Axis must move towards them in the Persian Gulf.’

Before this could happen, however, the Italo-German base in North Africa had to be made secure. The key to this was supply, and the key to supply was the elimination of Malta. Kesselring had set himself the task of 'neutralizing’ the island from the air, but the Italians had come to the conclusion that nothing less than its seizure would suffice. In this they were surely right, for whatever the short-term success of an aerial assault, it could not be maintained indefinitely, particularly when it depended almost entirely upon German aircraft which were always liable to recall to the Russian front. As early as October 1941, the Armed Forces Chief of Staff, General Ugo Cavallero (who replaced Ba-doglio in December 1940), had instructed the army to plan the invasion of Malta. By the beginning of 1942, the other services were involved and the Germans were also drawn in. At a meeting between Hitler and Mussolini at the end of April, it was decided to recapture Tobruk and advance as far as the Egyptian frontier by the middle of June, and then to take Malta before any further advance in North Africa.

Unfortunately for the Italians, however, they were dependent upon German help for the success of the Malta invasion,-and it soon became clear that Hitler was not very enthusiastic about the operation. In a meeting with his military advisers on 21st May, he argued that the Italians were really incapable of carrying out such a complex manoeuvre and that, in any case, their security was so bad that the British would soon know as much about the plans as their own commanders. In these circumstances, it was not surprising that, after the Italo-German forces had captured Tobruk on 21st June and Rommel, confident in the belief that he could be in Cairo by the end of the month, had pressed for the restrictions upon his advance to be lifted. Hitler urged Mussolini to let him have his way. 'Destiny has offered us a chance which will never occur twice in the same theatre of war,’ he wrote. 'The goddess of battles visits warriors only once. He who does not grasp her at such a moment never reaches her again.’ But the Duce did not need such lyrical prose to persuade him. He was as mesmerized by the prospect of conquering Egypt as Hitler or Rommel and, in spite of the reasoned objections of Cavallero and Kesselring, he gladly gave the German field commander his head. The Malta invasion was postponed — indefinitely as it turned out —and the Duce even went to North Africa to preside personally over the fall of Egypt.

But Egypt did not fall. Auchinleck held Rommel’s offensive and the initiative passed to the British with the second Battle of El Alamein in October. The following month, the Anglo-American landings in French North Africa (Operation Torch) put the Italo-German forces in a vice, and when they were finally expelled from Tunisia in May 1943, the way was clear for a direct assault upon Festung Europa ('Fortress Europe’) itself—by way of Italy.

Was Italy a liability?

Later in the war Adolf Hitler pondered upon the effects of his partnership with Italy. 'When I pass judgement, objectively and without emotion, on events,’ he wrote, 'I must admit that my unshakeable friendship for Italy and the Duce may well be held to be an error on my part. It is in fact quite obvious that our Italian alliance has been of more service to our enemies than to ourselves. Italian intervention has conferred benefits which are modest in the extreme in comparison with the numerous difficulties to which it has given rise. If, in spite of all our efforts, we fail to win this war, the Italian alliance will have contributed to our defeat.’

Italy’s presence at Germany’s side, he claimed, prevented him from mobilizing the Muslim peoples in his support, 'for the Italians in these parts of the world are more bitterly hated, of course, than either the British or the F’rench.’ On a more purely military level, the Italian defeats in Greece 'compelled us, contrary to all our plans, to intervene in the Balkans, and that in its turn led to a catastrophic delay in the launching of our attack on Russia. We were compelled to expend some of our best divisions there. And as a net result we were then forced to occupy vast territories in which, but for this stupid show, the presence of any of our troops would have been quite unnece. ssary. . . Ah! if only the Italians had remained aloof from this war!’

When reflections such as these are placed alongside the actual record of Italian performance during the Second World War, it is easy to see the basis for the belief that Italy was Germany’s Achilles heel. But is this belief justified? After all, it was not the Italian alliance which prevented Hitler from exploiting Arab nationalism, but his preoccupation with Barbarossa (the offensive against Russia). And even if that Operation could have been launched a few weeks earlier but for the German campaigns in Greece and Yugoslavia (which is very doubtful), would it have made all that much difference to the final outcome? As for the German troops allegedly tied down in the Balkans, these amounted to seven divisions in June 1941 compared with the 153 massed for Barbarossa. It is hard to see how they would have had much effect upon the balance of forces on the Eastern Front.

It was not so much Hitler’s support for Mussolini which contributed to his losing the Second World War, as his failure to give him adequate support by according the Mediterranean a higher priority in his overall strategy, as, for example, his naval advisers constantly urged. The Middle East was of great strategic importance to the British Empire, and a small increase in German resources devoted to the area could have resulted in proportionately large rewards. As it was, the main burden of Axis operations in the Mediterranean fell upon the Italians, who were totally incapable of shouldering it. The brilliant tactical successes of a commander like Rommel could obscure the harsh realities for a while, but by the end of 1942 they were plainly there for all to see, and Mussolini had cause to reflect upon the words of his fellow-Italian, Niccolo Machi-avelli; 'Everyone may begin a war at his pleasure, but cannot so finish it.’

The Battle of Britain

Of all the innumerable battles fought during the last 2,500 years, no more than fifteen have been generally regarded as decisive. A decisive battle has been defined as one in which 'a contrary event would have essentially varied the drama of the world in all its subsequent stages’. By this reckoning, the Battle of Britain was certainly decisive.

To find another decisive battle fought so close to British homes we have to go back to the defeat of the Armada in 1588, when Drake’s well-handled little ships, with some assistance from the weather, destroyed a vast array of Spanish warships. But a closer parallel is with the Battle of Trafalgar.

In 1805 Napoleon controlled the whole of Flurope west of the Russian frontier, with the exception of Great Britain and some parts of the Iberian peninsula. He understood very well that if he could destroy

British sea power he could invade and conquer that stubborn island kingdom, and the whole of Western Europe would fall under his sway. But at Trafalgar his own sea power was destroyed by Nelson’s fleet, and with it disappeared his hopes of subduing Great Britain. The narrow waters of the Channel were an insuperable barrier to his invading armies. Thwarted in the west, he turned against Russia, and his Grande Armee was all but destroyed amid the ice and snow during the terrible retreat from Moscow in the winter of 1812.

In August 1940 Hitler had mastered all Western Europe, apart from Great Britain, Spain, and Portugal. Although most of the men of the British Expeditionary Force had been brought home—the miracle of Dunkirk —they had lost almost all their weapons and equipment. This disaster had left Great Britain without any effective land forces, for in the whole country it

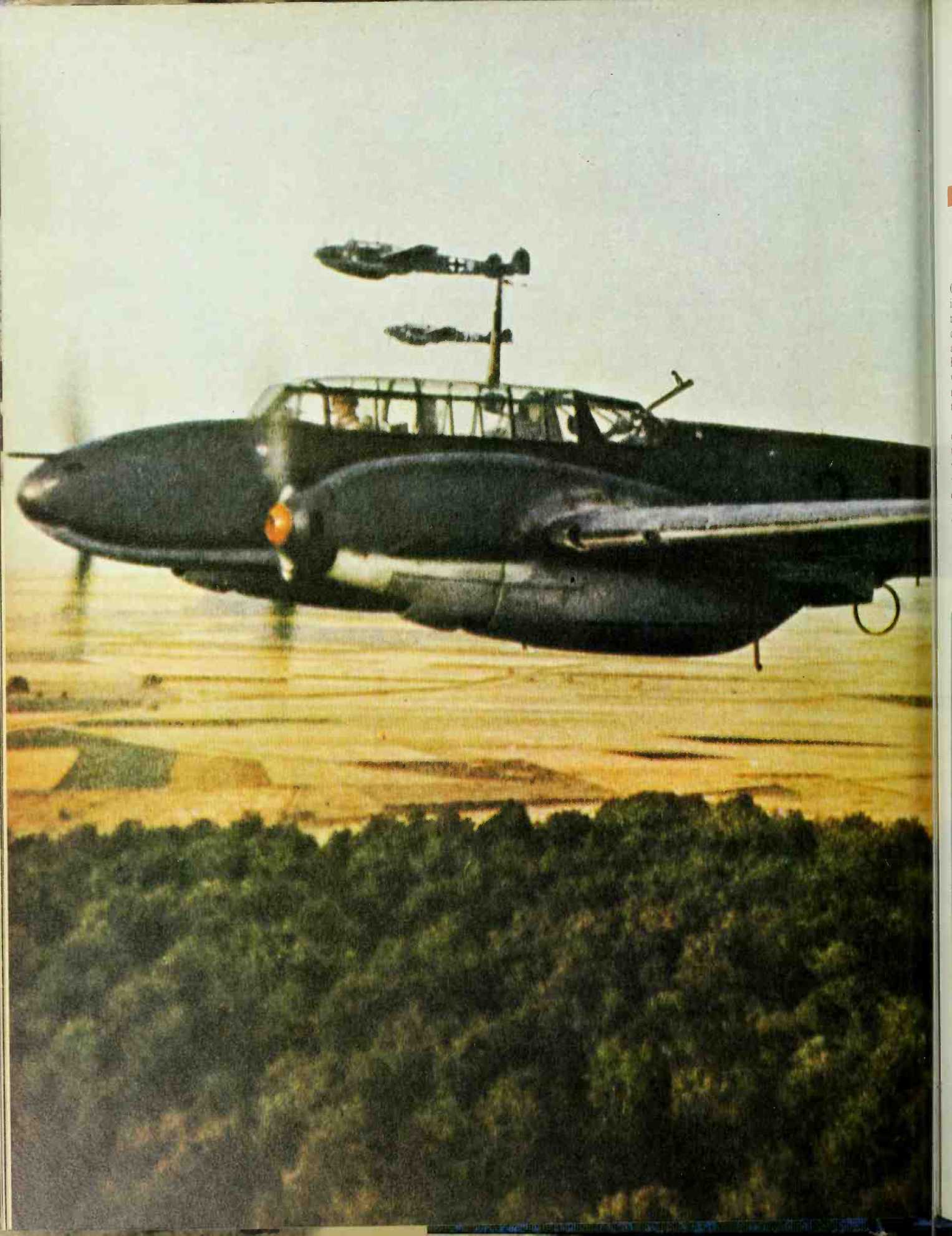

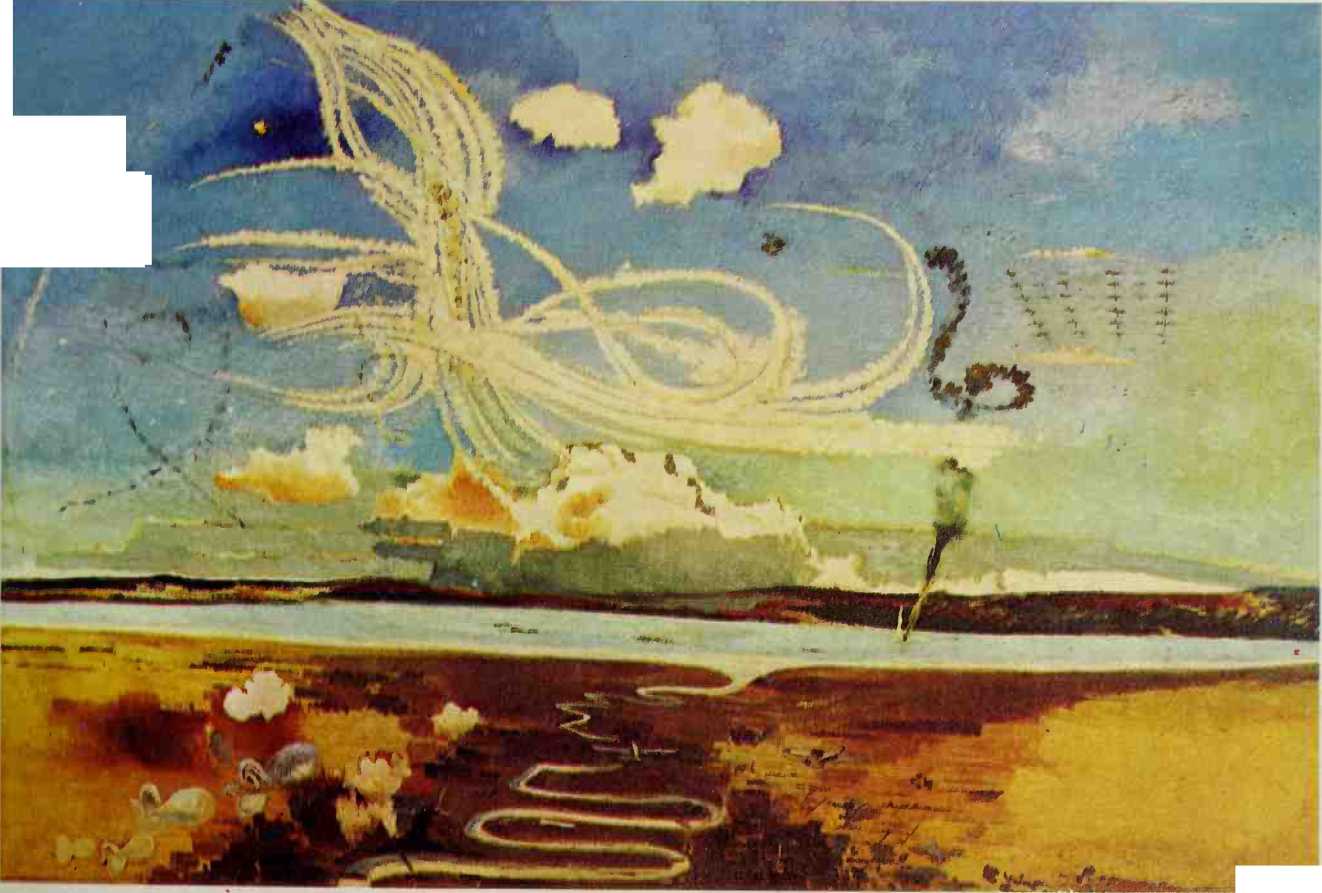

Left: The much vaunted Me,110 which proved a failure in the battle. Helow: 'The 'Battle of Britain' by Paul Nash, an artist during both wars

World History

World History