The German geographer Karl Haushofer believed that Germany’s defeat in World War I was caused by her leaders’ failure to appreciate the influence of geography. To overcome this deficiency Haushofer founded in 1922, in Munich, the Institut fur Geopolitik, which comprised geographers, political scientists, and economists. With these men he studied, among others, the works of Alfred T. Mahan, the sea-power historian, and Halford J. Mackinder, the British geographer and land-power theorist. Mahan attributed Britain’s imperial predominance to her sea power, and her sea power to such geographical factors as her insularity and her position athwart the sea communications of western Europe. Mackinder pointed out that sea and land power had dominated alternately in history. Mahan explained England’s rise; Mackinder explained her decline in relation to the continental powers.

The rising influence of land power was ascribed by Mackinder to steam and gasoline engines and the expanding networks of railroads and all-weather roads. Land transporation at last competed with sea transportation in cost and safety; moreover, distances were usually shorter and speed was greater. Hence, the interiors of continents became as accessible and exploitable as the rimlands, and they had the added advantage of being less vulnerable in time of war.

Mackinder called the Europe-Asia-Africa land mass the World-Island. Other lands, including the Americas, Britain, Japan, and Australia, he called satellites, because of their smaller areas and populations. The hinterland of Eurasia, including most of Siberia and European Russia, he called the Heartland, the earth’s largest and least vulnerable continental interior.

Writing in 1919, Mackinder did not believe that the Russians themselves would be able fully to reap the unique advantages of their Heartland. Germany, however, which he called a “going concern,” was in his

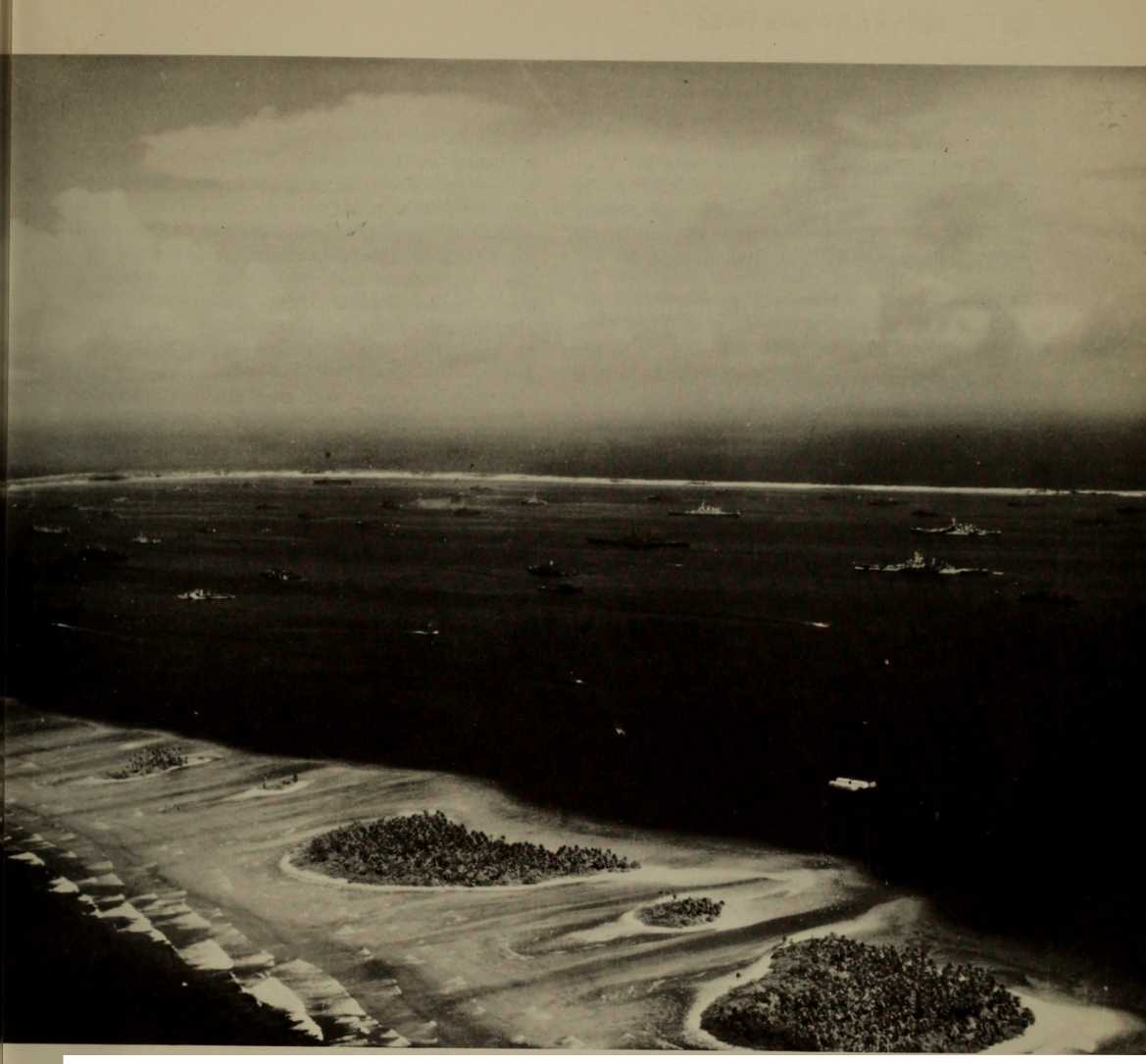

Service squadron in the lagoon of an atoll.

Opinion the nation geographically best placed and militarily most likely to capture and exploit the Heartland. Possessed of this base and its masses and resources, Germany could thrust outward to the oceans, seizing the seafaring nations and their ports from the landward side. Then, controlling all the resources of the World-Island, she could take to sea to conquer the rest of the world. Mackinder, in his book Democratic Ideals and Reality, expressed his views in a formula:

Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland:

Who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island: Who rules the World-Island commands the World.

The analysis that Mackinder intended as a warning to England Haushofer and his colleagues adopted as a blueprint for German aggression. From Haushofer’s pseudoscientific geopolitics Adolf Hitler derived most of his Lebensraum notions. Luckily for the Allies Hitler would not, or could not, heed Haushofer’s admonition to conquer the Heartland first and at all costs to avoid a second front. When the Germans invaded Russia in 1941, they were simultaneously engaged on several fronts. Thus overextended, they were defeated on all.

THE ROAD TO WORLD WAR II

In the early 1930s, at a time of worldwide economic depression, Germany, Italy, and Japan, each under a military dictatorship, set out to win prosperity and dominion through aggression against their neighbors. The failure of the major powers, particularly France and Britain, to take effective countermeasures destroyed the League of Nations and brought on World War II.

In the latter part of 1931 Japanese military leaders, in defiance of the Nine-Power Treaty, in defiance of the Kellogg-Briand Pact, in defiance indeed of their own government, launched an attack on the Chinese province of Manchuria, which they overran in a little more than three months. Protests from the United States and the League of Nations had no effect whatever on the aggressors. Secretary of State Stimson announced at last that the United States would not recognize Japan’s seizure of Manchuria. After Japan, in retaliation for a Chinese boycott of Japanese trade, landed troops at Shanghai and savagely massacred soldiers and civilians alike, the League adopted Stimson’s nonrecognition policy and demanded that the Japanese withdraw from Manchuria. Japan withdrew instead from membership in the League, and her militarists made good their control of the Japanese government by a process of selective assassination.

The spectacle of Japan defying international authority with utter impunity was not lost on Germany and Italy. Hitler withdrew Germany from the League of Nations;

1935 denounced all treaty limitations on German armaments and reestablished universal military service in the empire. That year the Italians, under the dictatorship of Benito Mussolini, invaded Ethiopia, which they annexed in 1936. The League of Nations denounced this act of bald aggression and temporarily imposed economic sanctions on Italy. Thenceforth Italy purchased from Germany the war-making materials which she could not buy from League members. She withdrew from the League and with Germany formed a Rome-Berlin Axis.

In 1936 Germany, in defiance'xff the Versailles Treaty and the Locarno Pact, remilitarized the Rhineland. In 1937 Japan launched a full-scale, though undeclared, war on China and quickly subdued most of the eastern half of that immense country. Japanese airplanes unerringly bombed American hospitals, schools, and churches in China. The Japanese government apologized for the sinking of U. S. gunboat Fancy in the Yangtze River, but evidence suggests that it was no accident. In 1938 German troops poured across the border into Austria, which Hitler seized and annexed as a province of his Nazi empire. Already the battle lines were being drawn in Spain, where a civil war, which flared up in 1936, had been expanded into a European conflict in miniature, with Germany and Italy actively supporting the rebel Nationalist Party, and Britain, France, and the Soviet Union directly or indirectly supporting the Loyalist government.

Whatever stiffness Britain had shown toward the aggressors from 1935 to 1938 had resulted chiefly from the influence of Anthony Eden, Britain’s tough-minded foreign secretary. The consequences had not been encouraging, for England had been repeatedly humiliated, and neither China, Ethiopia, nor Austria had been saved. Germany, Italy, and Japan were becoming more firmly aligned on one side, and France, Britain, and Russia were aligning themselves on the other. War impended. Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain therefore decided to jettison Eden and his policies and to try another tack. Reasoning that a tougher attitude might hasten war, he decided to try a little appeasement.

At once Chamberlain initiated a series of agreements with Italy. In return for promises by the Italians to muffle their anti-British propaganda and to withdraw their armed forces from Spain, Britain agreed to persuade the League of Nations to recognize Italy’s Ethiopian conquest. Consequently, League members recognized the King of Italy as Emperor of Ethiopia. This humiliat-

THE ROAD TO WORLD WAR II

159

Ing surrender by the League cost it its last remaining shreds of authority.

Chamberlain now prepared to bend the back to Hitler, who was making noisy declarations about German minorities in the Sudeten region of Czechoslovakia. The Sudeten Germans, who had been stirred up by Nazi agents and by Hitler’s speeches, were demanding nothing less than outright annexation to the German empire, and Hitler was declaring his determination to take the Sudetenland, if not peacefully, then by force. The Czechs mobilized and turned to France and Russia for help. Italy championed Germany because they were allies; Poland and Hungary did the same, because they hoped to get a piece of dismembered Czechoslovakia.

Prime Minister Chamberlain and Prime Minister Edouard Daladier of France flew to Munich to petition Hitler to keep the peace. Here they signed the notorious

Munich Agreement of September 29, 1938, which gave Hitler the Sudetenland in return for an empty promise: “This is the last territorial demand I have to make in Europe.”

On Chamberlain’s return to England, he announced: “It is peace in our time.” Six months later Hitler coolly annexed the greater part of Czechoslovakia, leaving the remainder for Poland and Hungary as a reward for their support. He then seized Memel from Lithuania and demanded Danzig from the Poles. Britain and France now abandoned their discredited appeasement policy and allied themselves with Poland. Russia, alienated by the Franco-British sell-out of Czechoslovakia, in August 1939 signed a nonaggression pact with Germany. Hitler, thus freed of threats from the east, on September 1 marched his armies into Polish territory. Two days later Britain and France declared war on Germany.

World History

World History