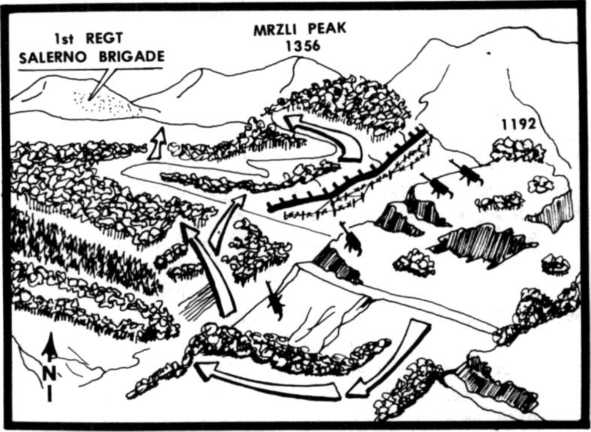

In spite of the exhaustion following the seizure of Mount Cragonza, I was unable to give my men a well-earned rest on the summit. The splendid Technical Sergeant Hugel took up his new job with his characteristic energy, exploited his limited forces to a maximum and, without waiting for support, attacked along the ridge rising toward Hill 1192 and Mrzli peak in order to gain as much additional ground as his weakened force would permit.

I sent orders by runners to the detachment to follow quickly over Mount Cragonza and to take the Matajur road in the direction of Mrzli peak. Then I joined the 2nd Company. A hundred yards farther on we ran into the enemy who was dug in on a wooded knoll on the ridge. On the east slope to our right the noise of combat increased considerably. Apparently rearward units of the Rommel detachment, climbing from Jecscek toward Cragonza, were being fired on or attacked. But it might have been units of the Alpine Corps attempting to climb the Matajur Road from Luico to Mount Cragonza.

Technical Sergeant Hugel was a past master at holding the enemy, who was superior in numbers and weapons, frontally and simultaneously attacking him in flank and rear with assault squads. These movements were accomplished in a few minutes and led to a repulse of the enemy, causing him to retire to the northeast, downhill toward Luico.

Since we attacked readily whenever we met the enemy, contact with our rear was soon broken. A report reached us that the detachment was being delayed by strong machine-gun fire from Italian positions northeast of Cragonza and was almost a mile behind me. Should I halt the 2nd Company at this point? No, we would stay on the attack against Mrzli Peak until we encountered a strong enemy force.

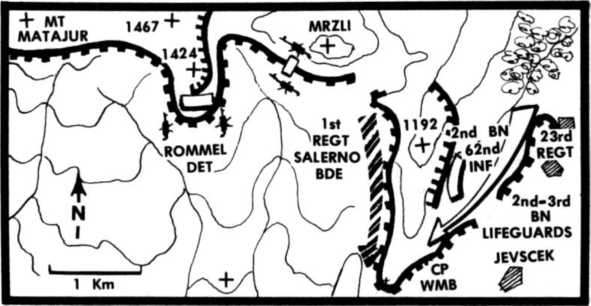

By 0830 the 2nd Company, having dwindled to a platoon with two light machine guns, captured Hill 1192 a mile and a half west of Avsa. The enemy prevented a further advance. He was in considerable strength half a mile northeast of Mrzli peak (1356) and plastered our newly won hilltop with heavy machine-gun fire. Lively fighting was in progress down the slope to the right, and also to the right rear in the direction of Jevscek. Alpine Corps units were attacking.

A minimum force required to attack the enemy on the southeast slope of Mrzli was estimated at two rifle companies and one machine-gun company. In order to assemble these forces quickly, I hurried to the rear down the Matajur road. Hugel had orders to hold Hill 1192. Even after searching far and wide I found no liaison officer of the trailing Rommel detachment. After rounding a curve seven hundred yards south of Hill 1192, I suddenly ran into an Italian detachment which was coming from the direction of Avsa and was crossing the Matajur road. The Bersaglieri grabbed their rifles and fired. A quick leap into the bushes just below the road saved me from the aimed fire. A few adversaries followed me down-slope through the bushes. But while they hastened down toward the valley, I was climbing toward Hill 1192. Arriving there, I ordered a fairly-strong scout squad to establish contact with the other units of the Rommel detachment and to give the various company commanders the order to close on Hill 1192 as soon as possible.7

I had to wait until 1000 before I had assembled a force equal to two rifle and one machine-gun company. These groups were composed of all companies of the Rommel detachment. Their approach to Hill 1192 was greatly delayed, because the various units were repeatedly involved in battles with the enemy, who was trying to retreat in a south-westerly direction across the Mount Cragonza— Hill 1192 line.

I felt we were strong enough to engage the Italian garrison on Mrzli. By means of light signals we asked for artillery fire on the hostile positions on the southeast slope of Mrzli peak, with the astounding result that German shells were soon striking there. Then the lively fire of the machine-gun company from Hill 1192 pinned the hostile garrison down in their positions while two rifle companies under my leadership came into close combat with the enemy just below the ridge road. We succeeded in turning the hostile west flank. Then we swung in against the flank and rear of the hostile position. But the enemy hastily withdrew when he saw us attacking in this direction and retired to the east slope of Mrzli. We took a few dozen prisoners. Since I did not intend to follow the enemy retreating on the east or north slopes of Mrzli, I broke off the engagement, continued my advance up the ridge road toward the south slopes of Mrzli and brought up the machine-gun company. (Sketch 57)

Already during our attack we had observed hundreds of Italian soldiers in an extensive bivouac area in the saddle of Mrzli between its two highest prominences. They were standing about, seemingly irresolute and inactive, and watched our advance as if petrified. They had not expected the Germans from a southerly direction —that is, from the rear. We were only a mile away from this concentration of troops. The Matajur road wound up over the partially-wooded south slope of Mrzli and, on the way west to the Matajur, passed just under the hostile encampment.

The number of enemy in the saddle on Mrzli was continually increasing until the Italians must have had two or three battalions massed there. Since they did not come out fighting, I moved near along the road, waving a handkerchief, with my detachment echeloned in great depth. The three days of the offensive had indicated how we should deal with the new enemy. We approached to within eleven hundred yards and nothing happened. Had he no intention of fighting? Certainly his situation was far from hopeless! In fact, had he committed all his forces, he would have crushed my weak detachment and regained Mount Cragonza. Or he could have retired to the Matajur massif almost unseen under the fire support of a few machine guns. Nothing like that happened. In a dense human mass the hostile formation stood there as though petrified and did not budge. Our waving with handkerchiefs went unanswered.

We drew nearer and moved into a dense high forest seven hundred yards from the enemy and thus out of his line of sight, for he was located about three hundred feet up the slope. Here the road bent very sharply to the east. What would the enemy up there do? Had he decided to fight after all? If he rushed downhill we would have had a man to man battle in the forest. The enemy was fresh, had tremendous numerical superiority, and moreover enjoyed the advantage of being able to fight downhill. Under these conditions I considered it a vital necessity to reach the edge of the wood below the hostile camp. But my mountain troopers with the heavy machine guns on their backs were so exhausted that I did not expect them to make the steep climb through dense underbrush.

Therefore, I allowed the detachment to continue marching along the road while Lieutenant Streicher, Dr. Lenz, a few mountain soldiers and I climbed on a broad front, about a hundred yard interval between men, and took the shortest route through the forest toward the enemy. Lieutenant Streicher surprised a hostile machine-gun crew and took it prisoner. We reached the edge of the forest unhindered. We were still three hundred yards from the enemy above

Sketch 57

Attack of Mrzli Peak. View from the southeast.

The Matajur road; it was a huge mass of men. Much shouting and gesticulating was going on. They all had weapons in their hands. Up front there seemed to be a group of officers. The leading elements of my detachment were not expected for some time and I estimated them to be at the hairpin turn seven hundred yards to the east.

With the feeling of being forced to act before the adversary decided to do something, I left the edge of the forest and, walking steadily forward, demanded, by calling and waving my handkerchief, that the enemy surrender and lay down his weapons. The mass of men stared at me and did not move. I was about a hundred yards from the edge of the woods, and a retreat under enemy fire was impossible. I had the impression that I must not stand still or we were lost.

I came to within 150 yards of the enemy! Suddenly the mass began to move and, in the ensuing panic, swept its resisting officers along downhill. Most of the soldiers threw their weapons away and hundreds hurried to me. In an instant I was surrounded and hoisted on Italian shoulders. “Evvrva GermaniaE* sounded from a thousand throats. An Italian officer who hesitated to surrender was shot down by his own troops. For the Italians on Mrzli peak the war was over. They shouted with joy.

Now the head of my mountain troops came up along the road from the forest. They moved forward with their habitual, easy but powerful mountaineer stride in spite of the hot sun and their heavy loads. Through an Italian who spoke German I ordered the prisoners to line up facing east below the Matajur road. There were 1500 men of the 1st Regiment of the Salerno Brigade. I did not let my own detachment halt at all, but I did call one officer and three men out of the column. Two mountain riflemen were assigned to move the Italian regiment across Mount Cragonza to Luico; and the disarming and removal of the 43 Italian officers, separated from their men, was entrusted to Sergeant Goppinger. The Italian officers became pugnacious after seeing the weak Rommel detachment and they tried to re-establish control over their men. But now it was too late. Goppinger performed his duty conscientiously.

While the disarmed regiment moved down toward the valley, the Rommel detachment moved past and just below the Italian camp ground. Some captured Italians had told me shortly before that the 2nd Regiment of the Salerno Brigade was on the slopes of Matajur; it was a very famous Italian regiment which had been repeatedly praised by Cadorna in his orders of the day because of outstanding achievements before the enemy. They assured me that this regiment would certainly fire on us and that we would have to be careful.

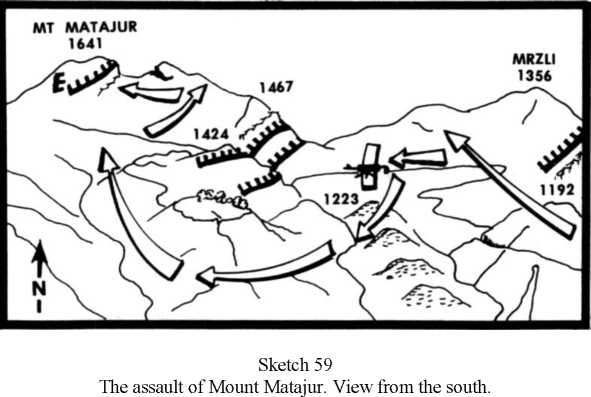

Their assumption was correct. The head of the Rommel detachment no sooner reached the west slope of Mrzli than strong machine-gun fire opened up from Hills 1467 and 1424. The hostile machine-gun fire was excellently adjusted on the road and soon swept it clear. Dense bushes below the road protected us from aimed fire. My men were soon under control and I continued the march, not below the Matajur road in the direction of Hill 1407 but in a sharp turn to the southwest. I wanted to cross Hill 1223 at the double and head toward the hairpin turn in the Matajur road just south of Hill 1424. Once there, then the 2nd Regiment of the Sa-‘ Long live Germany. (Pub) lemo Brigade could scarcely escape and would be in a position similar to that of the 1st Regiment a half hour before. The only difference would be that a withdrawal to the south across the bare slopes of Matajur would be prevented by our fire, whereas on Mrzli peak a covered retreat through the wooded zone had remained open to the Italians. (Sketch 58)

In order to deceive the enemy, I ordered a few machine guns to fire from the west slopes of Mrzli. With the rest of the detach-

Sketch 58

The situation before the attack of Mount Matajur.

Ment I reached the turn of the road seven hundred yards south of Hill 1424 without undergoing hostile fire, for the enemy was unable to observe our movement through thick clumps of bushes. I prepared a surprise attack on the garrison of Hill 1424, which was still firing on the rearward units of the Rommel detachment and on our machine guns on Mrzli. The success of the attack on Mrzli had caused us to forget all our efforts, our fatigue, our sore feet and our shoulders chafed by heavy burdens.

While I was expeditiously carrying out the preparations for the attack, ordering the machine-gun platoons in position, and organizing assault squads, the order came from the rear: —Wurttemberg Mountain Battalion withdraws.”8

The battalion order to withdraw resulted in all units of the Rommel detachment marching back to Mount Cragonza, except for the hundred riflemen and six heavy machine-gun crews who remained with me. Should I break off the engagement and return to Mount Cragonza?

No! The battalion order was given without knowledge of the situation on the south slopes of Matajur. Unfinished business remained. To be sure, I did not figure on further reinforcements in the near future. But the terrain favoured the plan of attack greatly and—every Wurttemberg mountain trooper was in my opinion the equal of twenty Italians. We ventured to attack in spite of our ridiculously small numbers.

Over on Hills 1424 and 1467 the defender was facing east among large rocks and he dove for cover when our unexpected machine-gun fire hit him from the south. The heavy fragmentation up there in the rocks considerably increased the effect of each shot. The hostile reaction was slight. Our machine guns had been emplaced in dense, high bushes, so that the enemy had trouble locating them.

I observed the splendid effect of our fire with the glass. When the first Italians tried to retire to the north slope of Hill 1424, I advanced my riflemen astride the Matajur road and on the west slope of Hill 1424. We advanced rapidly thanks to the strong fire support from the heavy machine guns. Over on the right the enemy completely vacated his positions on the east slope of Hill 1424 and his fire died out. (Sketch 59)

We kept attacking. The heavy machine guns were moved up in echelon. From Hill 1467 a hostile battalion tried to move off to the southwest by way of Scrilo. But the fire of one of our machine guns, delivered at sixty yards from the head of the column, forced the battalion to halt. A few minutes later, waving handkerchiefs, we approached the rocky hill six hundred yards south of Hill 1467. The enemy had ceased firing. Two heavy machine guns in our rear covered our advance. An unnatural silence prevailed. Now and then we saw an Italian slipping down through the rocks. The road itself wound among the rocks and restricted our view of the terrain to a few yards. As we swung around a sharp bend, the view to the left opened up again. Before us—scarcely three hundred yards away—stood the 2nd Regiment of the Salerno Brigade. It was assembling and laying down its arms. Deeply moved, the regimental commander sat at the roadside, surrounded by his officers, and wept with rage and shame over the insubordination of the soldiers of his once-proud regiment. Quickly, before the Italians saw my small numbers,

I separated the 35 officers from the 1200 men so far assembled, and I sent the latter down the Matajur road at the double, toward Luico. The captured colonel fumed with rage when he saw that we were only a handful of German soldiers.

Without stopping I continued the attack against the summit of Matajur. The latter was still a mile away and seven hundred

Feet above us and we could see through the glasses the garrison in position on the rocky summit. It apparently did not intend to follow the example of its comrades on the south slope of Matajur who had surrendered and were marching away. Lieutenant Leuze used his few machine guns to give fire support for the attack which we attempted on the shortest route from the south. But the hostile defensive fire was very heavy there, and the avenues of approach were so disadvantageous, that I preferred to turn to the east on the arched slope, unseen by the enemy, and attack the summit position from Hill 1467. During this movement small squads of Italians, with and without weapons, kept on moving toward the spot where the 2nd Regiment of the Salerno Brigade had laid down its arms.

We surprised an entire Italian company on the sharp east ridge of Matajur six hundred yards east of the peak. In total ignorance of events in its rear, it was facing the north slope and was engaged with scout squads of the 12th Division who were climbing toward Matajur from Mount Delia Colonna. Our sudden appearance on the slope, in the rear with weapons at the ready, forced this enemy to surrender at once without resistance.

While Lieutenant Leuze fired on the garrison of the summit with a few machine guns from a south-easterly direction, I climbed with the other units of my small group in a westerly direction along the ridge and toward the summit. On a rocky knoll a quarter of a mile east of the peak, other heavy machine guns went into position as fire support for the assault team disposed on the south slope. But before we opened fire, the garrison of the summit gave the sign of surrender. One hundred and twenty more men waited patiently until we took them prisoner at the ruined building (border guardhouse) on the summit of Matajur (1641). A scout squad of the 23rd Infantry Regiment, consisting of a sergeant and six men, met us during its climb from the north.

At 1140 on October 26, 1917, three green and one white flare announced that the Matajur massif had fallen. I ordered a one-hour rest on the summit. It was well deserved. 9

Round about we saw the mighty mountain world in radiant sunshine. Our view reached far: In the northwest the Stol lay six miles away and was being attacked by the Flitsch Group. In the west we saw Mount Mia (1228) far below us. We could not see into the Natisone valley, though it lay only two miles away and forty-seven hundred feet below us. In the southwest were the fertile fields around Udine, Cadorna's headquarters. In the south the Adriatic glittered. In the southeast and east were the mountains so well known to us: Cragonza, Mount San Martino, Mount Hum, Kuk, Hill 1114.

That war was still round about us was indicated by the prisoners sitting amongst us, by weak artillery fire, and by an air battle, in which an Italian machine plunged burning into the depths. Nothing was to be seen of our neighbours. I dictated the combat report which Major Sproesser demanded every day to Lieutenant Streicher.

Observations: The capture of Mount Matajur occurred fifty-two hours after the start of the offensive near Tolmein. My mountain troopers were in the thick of battle almost uninterruptedly during these hours and formed the spearhead of the attack by the Alpine Corps. Here—carrying heavy machine guns on their shoulders— they surmounted elevation differences of eight thousand feet uphill and three thousand downhill, and traversed a distance of twelve miles as the crow flies through unique, hostile mountain fortifications.

In twenty-eight hours five successive and fresh Italian regiments were defeated by the weak Rommel detachment. The number of captives and trophies amounted to: 150 officers, 9000 men, and 81 guns. Not included in these figures were the enemy units which, after they had been cut off on Kuk, around Luico, in the positions on the east and north slopes of Mrzli peak, and on the north slopes of Mount Matajur, voluntarily laid down their arms and joined the columns of prisoners moving toward Tolmein.

Most incomprehensible of all was the behaviour of the 1st Regiment of the Salerno Brigade on Mrzli. Perplexity and inactivity have frequently led to catastrophes. The councils of the mass undermined the authority of the leaders. Even a single machine gun, operated by an officer could have saved the situation, or at least would have assured the honourable defeat of the regiment. And if the officers of this regiment had led their 1500 men against the Rommel detachment, Mount Matajur would surely not have fallen on October 26.

In the battles from October 24 to 26, 1917, various Italian regiments regarded their situation as hopeless and gave up fighting prematurely when they saw themselves attacked on the flank or rear. The Italian commanders lacked resolution. They were not accustomed to our supple offensive tactics, and besides, they did not have their men well enough in hand. Moreover, the war with Germany was unpopular. Many Italian soldiers had earned their livings in Germany before the war and found a second home there. The attitude of the simple soldier toward Germany was clearly displayed in his “Evviva Germania!" on Mrzli.

A few weeks later the mountain soldiers had Italian troops opposing them in the Grappa region, who fought splendidly and were men in every particular, and the successes of the Tolmein offensive were not repeated.

The evaluation of the successes of the Wurttemberg mountain troops in the first days of the Great Battle is evident in the orders of the day of the German Alpine Corps (General von Tutschek) of November 3, 1917, which states among other things: “The capture of the Kolovrat Ridge caused the collapse of the whole structure of hostile resistance. The Wurttemberg Mountain Battalion under its resolute leader, Major Sproesser, and his courageous officers was the main one active here. The capture of the Kuk, the possession of Luico, and the penetration of the Matajur position by the Rommel detachment initiated the irresistible pursuit on a large scale. ”

The losses of the Rommel detachment in the three days of attack were happily low: 6 dead, including 1 officer; 30 wounded, including 1 officer.

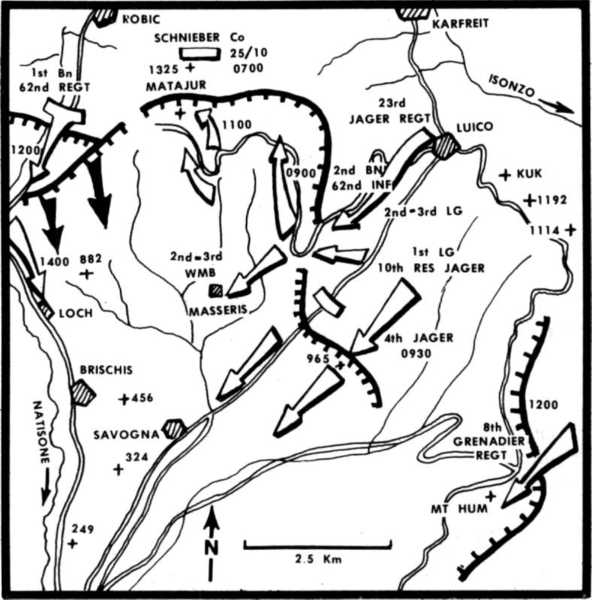

At noon on October 26, 1917, the order of battle in the Flitsch-Tolmein sector stood as follows: (Sketch 60)

Kraus Group: Forward units resting in Bergogna. Hostile attack on the Passo di Tanamea was repulsed.

Stein Group: In the 12th Division sector an attack by the 62nd and 63rd Infantry Regiments was under way in the Natisone valley from the border across Stupizze toward Loch. The latter was reached around 1400. From the north no forces were in position to attack the Italian position on the Matajur-Mrzli line. The 23rd Infantry Regiment marched over Cragonza toward Matajur reaching Cragonza around noon. In the Alpine Corps the Rommel detachment of the Wurttemberg Mountain Battalion took Mrzli and Matajur. The bulk of the Wurttemberg Mountain Battalion under Major Sproesser was descending from Mount Cragonza toward Masseris. The 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the Life Guards followed him; the 1st Battalion of the Life Guards and the 10th Reserve Jager Battalion started the advance toward Polava at 1000, after the enemy had vacated his positions near Polava. In the 200th Division the 4th Jager Regiment took Mount San Martino by 0930 and then advanced in the direction of Azzida.

Scotti Group: The 8th Grenadier Regiment took Mount Hum during the forenoon. The 1st Imperial and Royal Division continued the attack through Cambresko toward St. Jakob.

The result was: The forces of the 12th Division and the Alpine Corps around Luico advanced in a south-westerly direction only after the Italian positions on Mount Cragonza had been taken and the Salerno Brigade on Mrzli and Matajur had been taken

Sketch 60

The situation at noon, October 26, 1917.

By the leading units of the Wurttemberg Mountain Battalion. Also the attack of the 12th Division in the Natisone Valley northwest of the Matajur massif, which was reached in the night of October 24-25, made gains only after the enemy on Matajur had been captured.

World History

World History