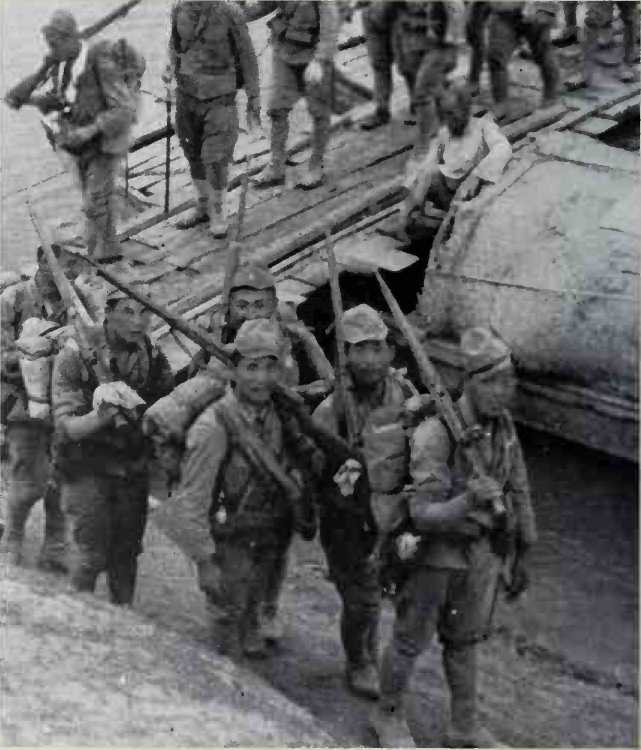

Japanese soldiers, armed with Arisaka M38's, cross a pontoon

Bridge.

Like the Italian, the Japanese soldier went to war with only an ordinary bolt action rifle. The Japanese rifle was the Arisaka M38, or Meiji 38 model (the 38 corresponds to the year 1905, the 38th year of the Meiji Dynasty), also known as the Ml 905.

Using the Mauser mechanism as a starting point, the Japanese adapted and improved their original 1897 model, adding a bulbous safety knob at the back of the bolt and redesigning the striker mechanism. An additional modification was the use of a metal bolt cover which served as protection against extreme weather conditions for the mechanism. One notable failing, however, was its lack of robustness and issuing of clattering noise which gave away the position of the firer-many Arisaka 38's were "lost in action" with little regret.

The original Arisaka M38 measured 50.2 inches long and weighed 9i pounds. The Mauser-type magazine was fitted into the body. The bullet weighed 9 grams and had a muzzle velocity of 2,400 f. p.s.

Yet the M38 was an old-fashioned weapon with 6.5-mm calibre ammunition, like the Italian Carcano, and in 1939 the Japanese decided to increase the calibre of their rifles and produced the Type 99. The calibre chosen was the more powerful 7.7-mm-equivalenttothe British .303-inch, and the bullet, weighing 11.34 grams, had a muzzle velocity of 2,600 f. p.s. But in spite of its modernisation, because of manufacturing and supply problems, the earlier 6.5-mm rifle was much more widely used than the 7.7-mm model during World War II.

Variations on the basic design included the Arisaka Ml 938 carbine. Although originally designed for artillery and cavalry troops, being about a foot and a half shorter than the rifle and

About seven ounces lighter, it was much favoured by the infantry.

The M97 sniper's rifle was a modified Arisaka in which the bolt handle was turned down to prevent the hand of the firer obscuring the sight. Used with a bipod and with a telescope off to the left it could be charger loaded.

I

At the beginning of March 1942 Japanese bombs were falling on the eastern half of New Guinea, the great jungle-covered island off the northern coast of Australia. The bombers came from Rabaul on the island of New Britain, to the east.

Rabaul, the capital of territory mandated to Australia at the end of World War I, which included the Bismarcks and a strip along the northern coast of New Guinea, had been captured on January 23 by the Japanese Army’s 5,000-man South Seas Detachment (Major-General Tomitaro Horii) supported by the Navy’s 4th Fleet (Vice-Admiral Shigeyo-shi Inouye). Sailing into its spacious harbour, ringed by smoking volcanoes, the invaders in a few hours forced the small Australian garrison to scatter into the hills.

The Japanese found Rabaul "a nice little town”, with wide-eaved bungalows surrounded by red hibiscus. General Horii, the conqueror of Guam, rounded up the white civilians and sent them off to Japan in the transport Montevideo Maru (they were all lost en route when the ship was sunk by an American submarine). Then he began building an air base. Admiral Inouye helped to make the

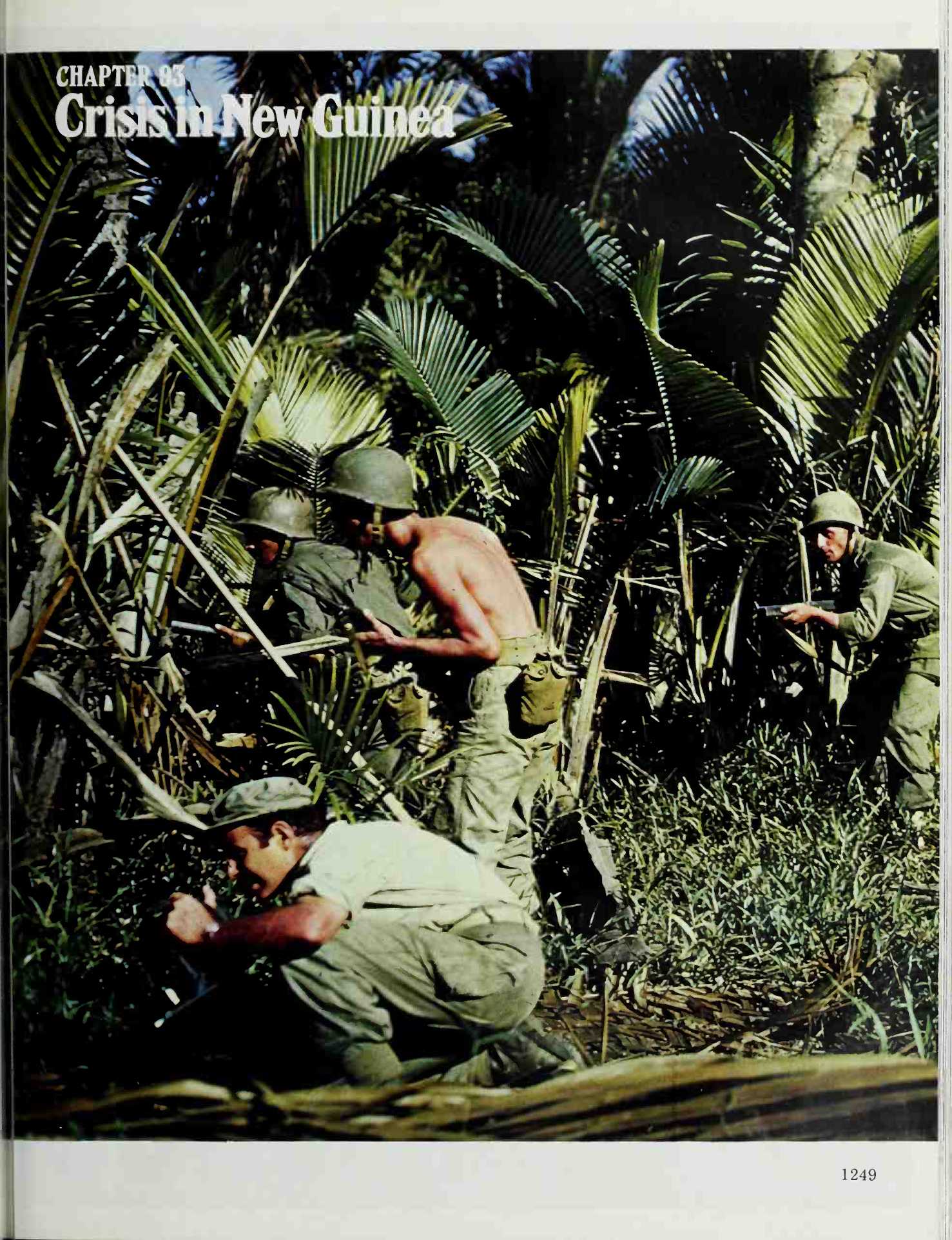

A They saved Port Moresby and turned the tide in the Owen Stanleys: Australian troops, fording a river in New Guinea.

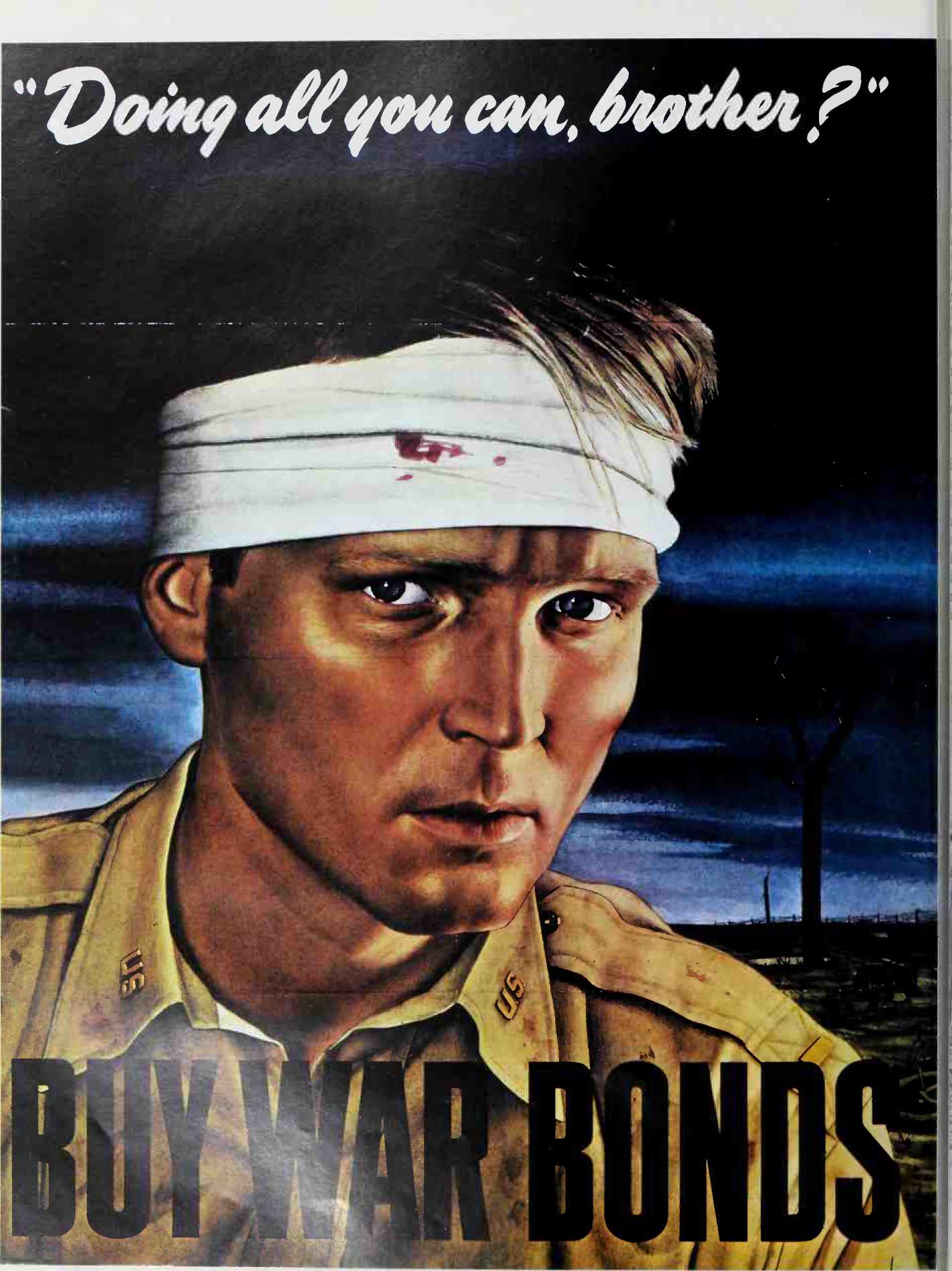

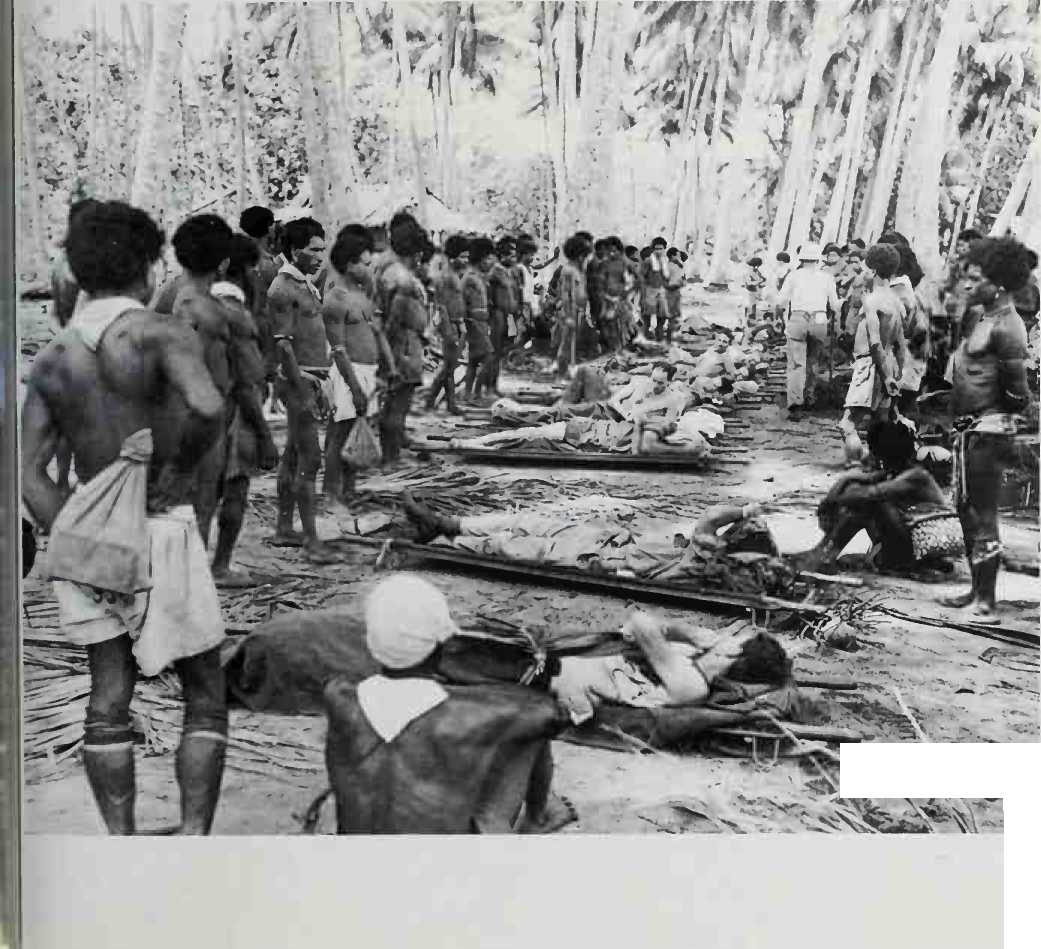

<1 Native stretcher-bearers in New Guinea resting in a coconut grove, while carrying American front-line wounded to hospitals. <]<i In this American poster an appeal to buy war bonds comes from a battered young lieutenant, on a battlefield rather reminiscent of World War I.

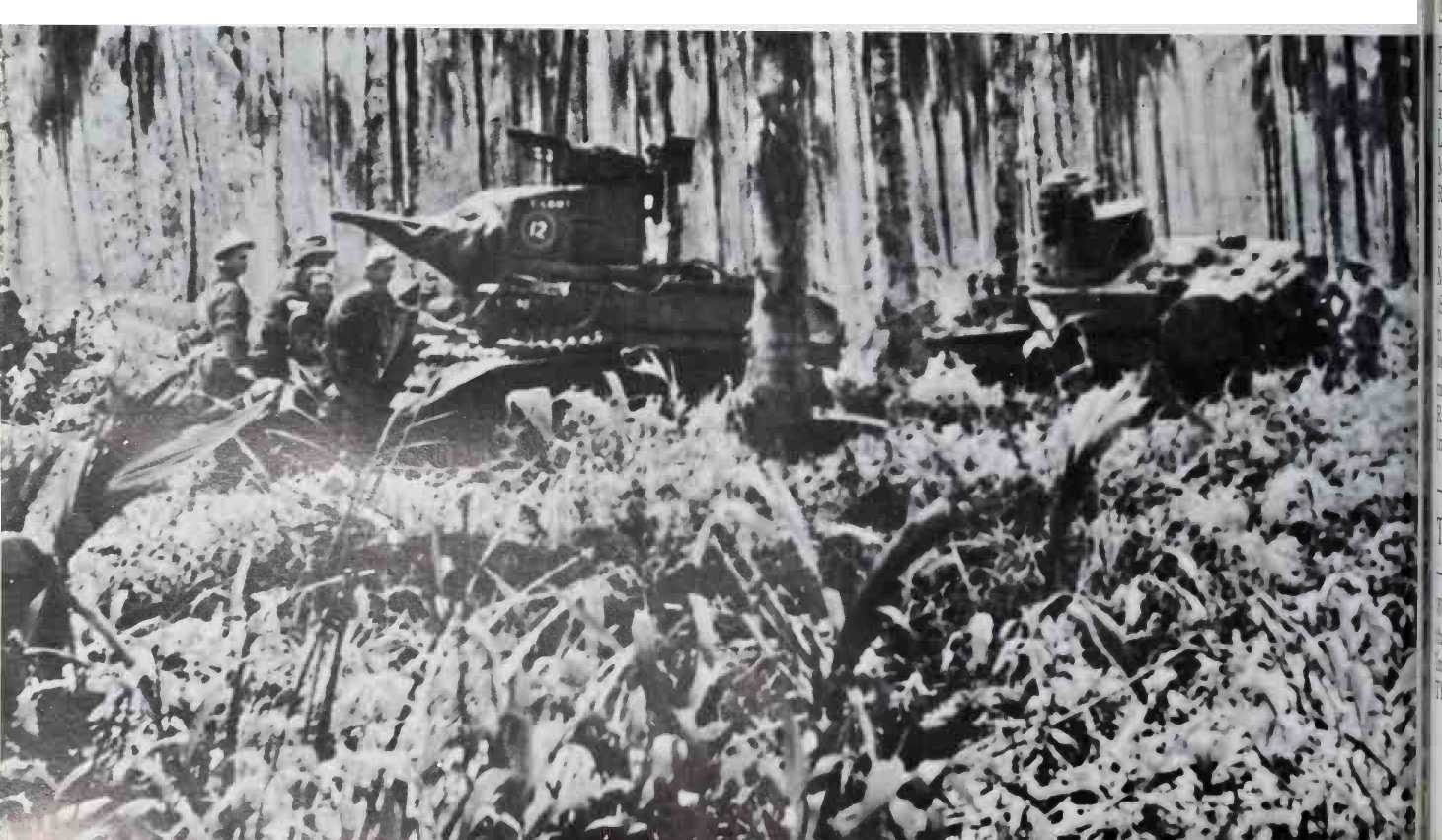

(Page 1249): More muscle from the Americans; a U. S. platoon in the New Guinea jungle.

V Equally at home in Alamein sand or New Guinea jungle: the familiar, rangy silhouette of the Ameriean Stuart light tank.

Connaissance.

To facilitate the bombing of Port Moresby, some 550 miles from Rabaul,

Base secure by occupying Kavieng on New Ireland to the north. To the southeast, bombing took care of Bougainville, northernmost of the long string of Solomon Islands.

The towns of Lae and Salamaua, in the Huon Gulf in the east of New Guinea, had been heavily bombed in the preliminary attack on Rabaul on January 21. The civilians fled, some on foot to the wild interior, some in native canoes down the Solomon Sea, hugging the New Guinea coast. One party, after a voyage of about two weeks, put in at Gona, an Anglican mission on the coast in Australia’s own Territory of Papua, in the south-east of New Guinea.

The arrival of the refugees from the Mandated Territory was long remembered by Father James Benson, the priest at Gona. The big sailing canoes against a flaming sunset sky brought through the surf "thirty-two woefully weatherbeaten refugees whose poor sun - and salt-cracked lips and bearded faces bore evidence of a fortnight’s constant exposure.’’_ With only the clothes they fled in, "they looked indeed a sorry lot of ragamuffins”. Next morning they began the five-day walk to Kokoda, a government station about 50 miles inland. From there planes could take them to Port Moresby, the territorial capital on the Coral Sea, facing Australia.

Planes flying from Kokoda to Port Moresby had to skim the green peaks of the Owen Stanley Range, the towering.

Jungle-covered mountain chain that runs the length of the Papuan peninsula. After? a flight of about 45 minutes they put down at a dusty airstrip in bare brown foothills. From the foothills a road descended to Port Moresby, in peacetime a sleepy copra port with tin-roofed warehouses baking in the tropical sun along the waterfront. A single jetty extended into a big harbour; beyond, a channel led to a second harbour large enough to have sheltered the Australian fleet in World War I.

Because of its fine harbour and its position dominating the populous east coast of Australia, Port Moresby was heavily ringed on military maps in Tokyo. On orders from Imperial General Headquarters the first air raid was launched from Rabaul on February 3. The bombers did a thorough job and returned unscathed. Port Moresby’s handful of obsolete planes and small anti-aircraft guns was no match for modern Japanese aircraft.

Star of the Japanese air fleet was the Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighter-bomber, one of the best planes of the war. Armed with two 20-mm cannon and two 7.7-mm machine guns, it could carry 264 pounds of bombs and was fast and agile. Its range of 1,150 miles and ceiling of 32,800 feet also made it invaluable for re

A A dense column of smoke marks the grave of an Allied plane, destroyed in a surprise Japanese raid on the air base at Port Moresby.

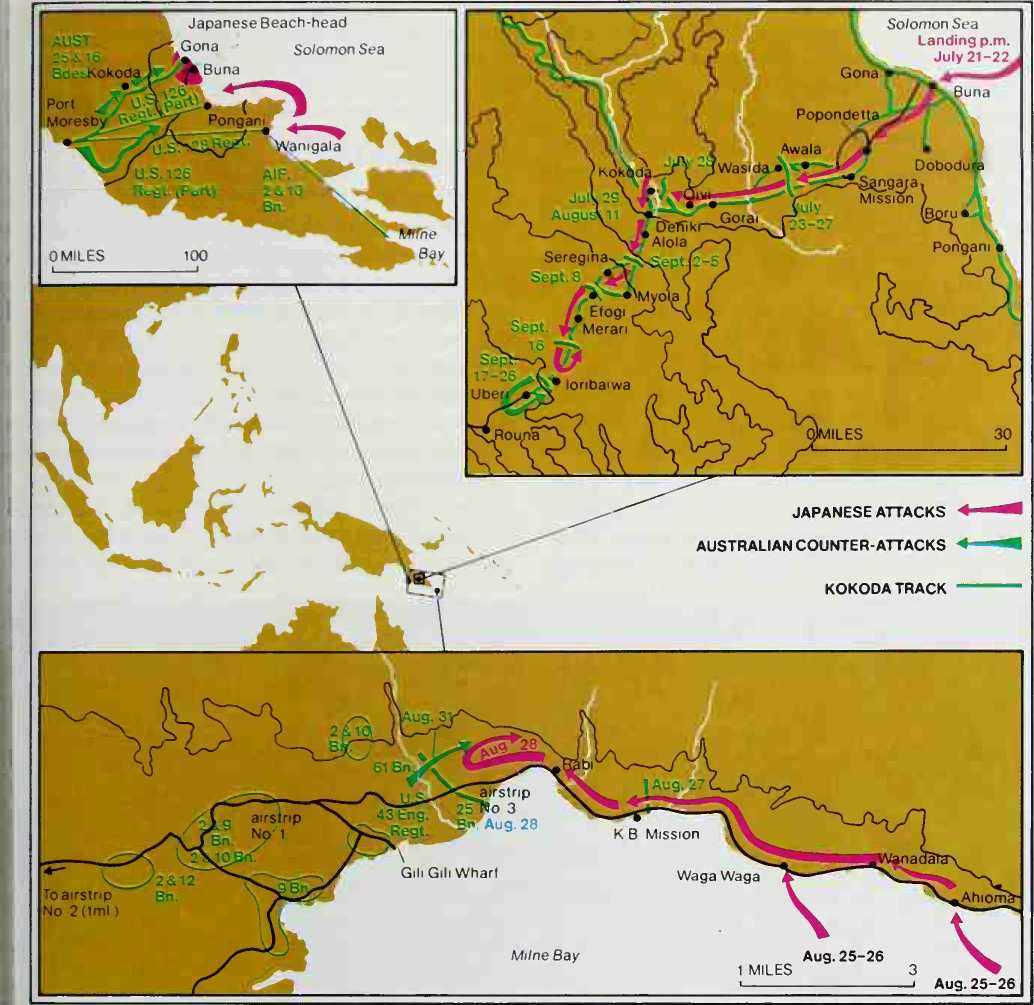

<] The Japanese attacks and Australian counter-attacks on New Guinea.

V Australian soldiers survey the bodies of four dead Japanese, killed in the destruction of their jungle pillbox.

Tokyo ordered General Horii to occupy Lae and Salamaua, Lae to be used as an advanced air base, Salamaua to secure Lae. At 0100 hours on the morning of March 8 a battalion of Horii’s 144th Regiment made an unopposed landing at Salamaua-the first Japanese landing on New Guinea. An hour later Inouye’s Maizuru 2nd Special Naval Landing Force (S. N.L. F.) marines occupied Lae. The naval force, which included engineers and a base unit, then took over at Salamaua. Horii’s infantrymen returned to Rabaul to await orders for the next move in the south-west Pacific.

World History

World History