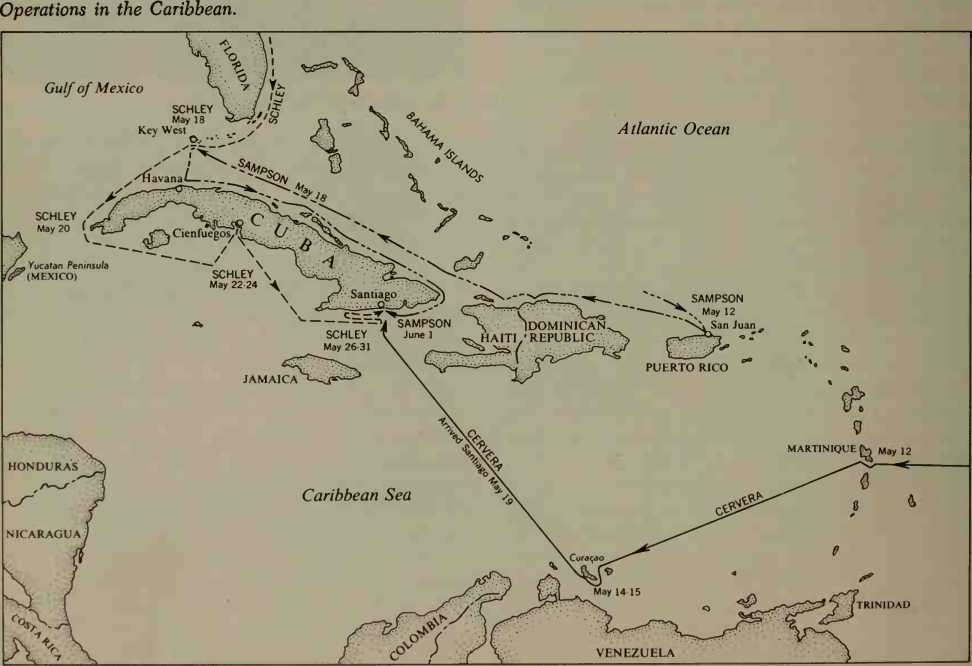

When Admiral Sampson learned that Admiral Cervera had left the Cape Verde Islands, he assumed that the latter would put in for coal at Puerto Rico, the only Spanish base between the Cape Verdes and Cuba. On May 3, therefore, Sampson lifted the blockade of a considerable stretch of Cuban coast, and with the Indiana, the Iowa, his flagship New York, two monitors, and several lesser craft, headed for the other Spanish island. Speed was deemed essential, because Cervera was expected to arrive in the West Indies on May 8. On that date, however, a deeply frustrated Sampson was ofiF Haiti struggling with his monitors, which were so slow that they had to be towed; moreover, they kept breaking down or parting their tow lines. When the Americans arrived off San Juan, Puerto Rico, on the 12th, they found no sign of Cervera, who was a little too wily to make so obvious a landfall.

While Sampson was venting his frustrations and, incidentally, risking his ships and men in a useless bombardment of San Juan’s defenses, a cablegram reached the Navy Department from the U. S. consul on Martinique reporting that Cervera’s squadron had appeared off that island. This was shocking news, for not only was the north Atlantic squadron divided into several sections, but the Oregon, having circumnavigated South America, was now headed for the very waters where Cervera was reported to be.

The Navy Department promptly ordered the Flying Squadron to Key West, whither Sampson also sped with his swiftest vessels, leaving the cumbersome monitors to get back to base as best they could. Schley and Sampson both arrived at Key West on May 18, to learn that Cervera had dropped off at Martinique a destroyer that had been disabled by the Atlantic crossing, and then had touched at the Dutch island of Curasao.

This news meant that the Oregon was safe, but it provided no clue to Cervera’s destination. The Navy Department, basing its estimate on information that the Spanish squadron was bringing munitions for the defense of the Cuban capital, concluded that Cervera would attempt to reach Havana, or that he was bound for the southern port of Cienfuegos, which was connected to the capital by rail. Sampson therefore o/dered

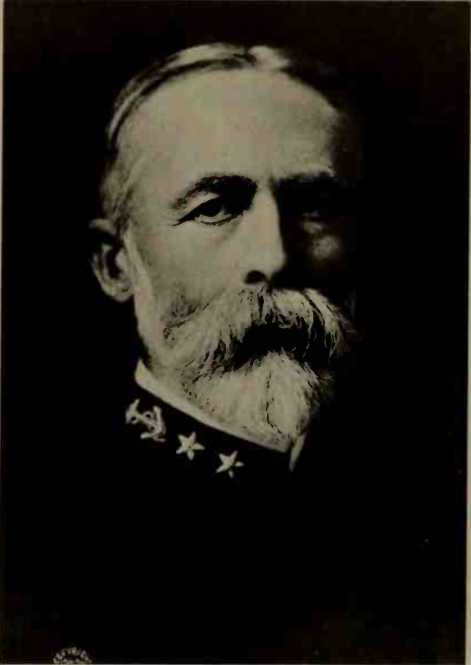

William T. Sampson.

The Flying Squadron, reinforced by the Iowa, to pass around west of Cuba to blockade Cienfuegos, while he himself guarded the approaches to Havana.

Both the department’s information and its conclusion were erroneous. Cervera was bringing no munitions for Havana. Short of coal, he had steamed straight from Curasao to the nearest harbor of refuge, the relatively isolated southeastern port of Santiago de Cuba, which he entered on May 19.

Schley’s operations during the next few days have been the subject of so much controversy that it is difficult to know how to describe them fairly. A postwar court of inquiry pronounced them “characterized with dilatoriness, vacillation, and lack of enterprise,” but this verdict has not won universal concurrence.

Because the Navy’s overriding objective was locating and destroying Cervera’s squadron, or at the very least blockading it tightly in port, one might have expected Schley to dash to his destination. Instead, the Flying Squadron, belying its name, poked around to Cienfuegos at an average speed of 10 knots. The commodore’s explanation was that, anticipating a lengthy blockade, and possibly a battle, he was sensibly conserving coal.

Arriving off Cienfuegos on May 22, Schley could not see inside the harbor, but observing smoke and hearing what he took to be a gun salute, he concluded that the enemy squadron was inside. Meanwhile, evidence was piling up in Washington that the Spanish ships were at Santiago. Sampson rushed this information to Schley by fast dispatch boat, adding: “If you are satisfied that they are not in Cienfuegos, proceed with all dispatch, but cautiously, to Santiago de Cuba, and if the enemy is there, blockade him in port.”

Because the Cienfuegos area was strongly held by the Spaniards, who would probably capture any spies he sent ashore, Schley was at a loss how to get the information he needed. Among reinforcements arriving on May 24, however, was the cruiser Marblehead, whose commanding ofiBcer had earlier made contact with rebels ashore. From these reinforcements Schley now learned that the Spanish squadron was definitely not present.

Within a few hours Schley’s squadron was en route to Santiago. The 315-mile run took two days because his gunboats, which were slow, had additional diflBculty riding the rough seas; Schley had not felt justified in leaving them behind in waters where Cervera’s ships might be prowling. Some 22 miles from Santiago, he made contact with three American scout cruisers, which reported that, although they had been in the area several days, they had seen nothing of the Spanish squadron.

Schley, feeling that he had come on a wild goose chase, now began to worry about his coal supply. Although he had a collier with him, he considered the weather too rough for coaling at sea. He therefore signaled his ships to get underway on a westerly course for a return to Key West. This was the beginning of the famous “Retrograde Movement,” for which Schley was later sharply criticized.

Progress at first was exceedingly slow because the collier developed engine trouble and had to be taken in tow. Hence the next morning a scout cruiser was able to overtake the squadron and to deliver a cable from Washington via Haiti: “All Department’s information indicates Spanish division is still at Santiago de Cuba. The Department looks to you to ascertain facts, and

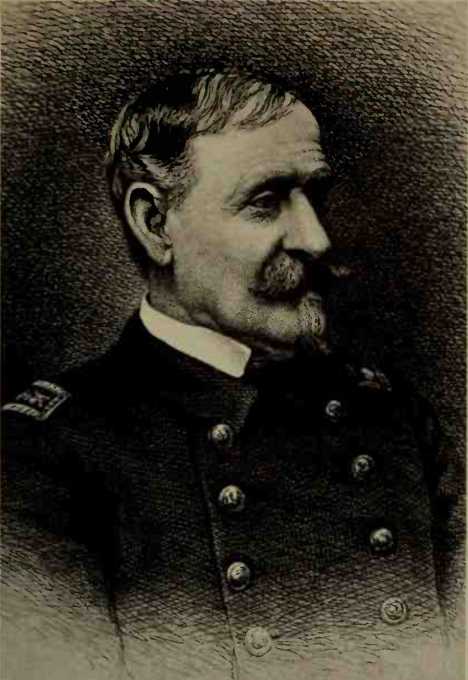

Winfield Scott Schley.

That the enemy, if therein, does not leave without a decisive action.”

Schley sent back a reply in which he stressed his coaling difiBculties and concluded with the regret that the “Department’s orders cannot be obeyed, earnestly as we have all striven to that end. I am obliged to return to Key West, via Yucatan Passage for coal. Can ascertain nothing concerning enemy.” When this reply, so shocking to the Navy Department, was relayed to Sampson, he decided that if Schley was coming back to Key West, he himself had better go to Santiago.

The Flying Squadron steamed westward until the evening of May 27 when, the wind having abated, Schley ordered his ships to coal at sea. The squadron then headed back to Santiago. There, on the morning of the 29th, the Cristdbal Coldn, Cervera’s best cruiser, was clearly visible, awnings spread, at the harbor entrance, where she had been for the past four days. On the 31st, Schley conducted an eight-minute bombardment'of the

Coldn and the harbor forts at such extreme ranges that no damage was done. The next day Sampson reached Santiago with reinforcements, including the newly arrived Oregon, whereupon the Coldn withdrew into the inner harbor. The Americans then established a close blockade.

Sampson had known of the Flying Squadron’s return to Santiago, but he decided, in view of Schley’s recent actions, that he had better come anyway and take personal command of operations. On his arrival Sampson expressed no disapproval of Schley! s conduct, but afterward, in a secret message to Secretary Long, he characterized it as “reprehensible.”

Sampson arranged his blockaders in a semicircle off the harbor entrance, the battleships in the center and the smaller vessels in the wings. At night all the ships drew in closer and a searchlight was directed into the channel. On the night of June 3, in order to prevent the escape of the Spanish squadron should the blockaders be blown off station by a storm. Lieutenant Richard P. Hobson attempted, with a volunteer crew, to seal the ships inside the harbor by sinking a collier athwart the narrow, winding entrance channel. But fire from the flanking Spanish batteries smashed the collier’s steering gear so that she drifted past the narrows and sank at a point where she presented no serious obstacle. On June 18 American marines went ashore some 40 miles to the east of Santiago and, in the first fighting on Cuban soil, seized Guantanamo Bay for use as a coaling and operational base.

Sampson at last concluded that, if Cervera’s squadron would not come out of the harbor, he must go in and get it. First, however, the channel had to be swept clear of mines, lest one of his ships in midcolumn should be sunk and block those inside from those still outside. So he called on the Army for troops to capture the batteries at the channel mouth in order that he might send in boats to clear the mines. The Army, eager to participate in the campaign, readily complied, sending from Tampa an expeditionary force of 16,000 soldiers led by Major General William R. Shafter, a sixty-three-year-old Civil War veteran. With naval support and aid, the soldiers began to go ashore with their equipment at Daiquiri, 16 miles east of Santiago. The landing, which began on June 22, took four days and was carried out in such wild disarray that it surely would have been thrown back had there been any opposition.

During the landing Sampson and Shafter conferred, but succeeded only in thoroughly confusing each other. The general, instead of attacking the Spanish batteries, plunged into the jungle and headed for Santiago. At the outskirts of the city after a bloody battle, Shafter, who

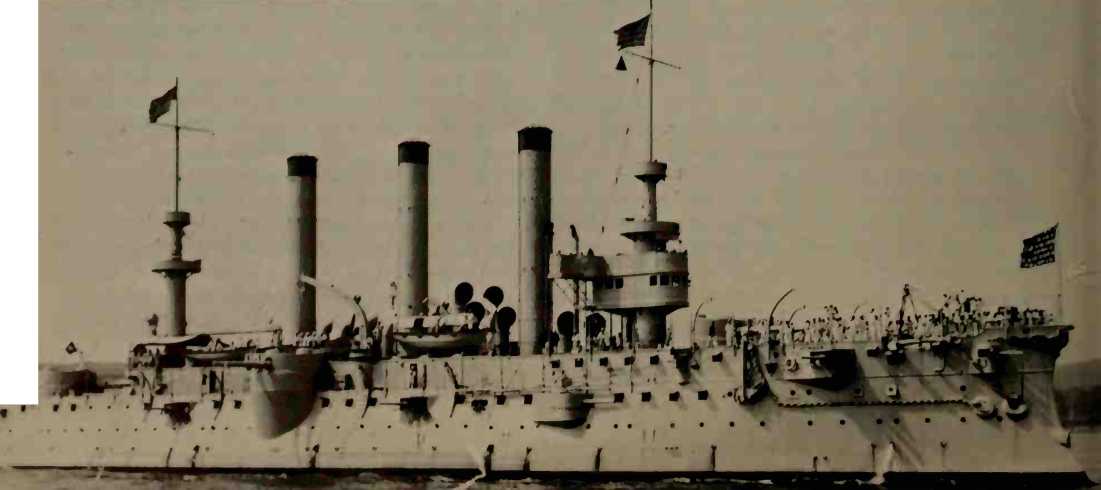

Weighed 300 pounds, and was feverish from the heat, fired off a hysterical message to Sampson urging him to “force the entrance” and to bring his ships into Santiago harbor in order to support the Army. Sampson, exasperated by this reversal of assigned Army-Navy roles and unable to reach an understanding with the general by messenger, on July 3 turned the tactical command over to Schley. He then headed east along the coast in the New York for a personal interview with Shafter. The blockade was further weakened that morning by the absence of the battleship Massachusetts, then coaling at Guantanamo Bay.

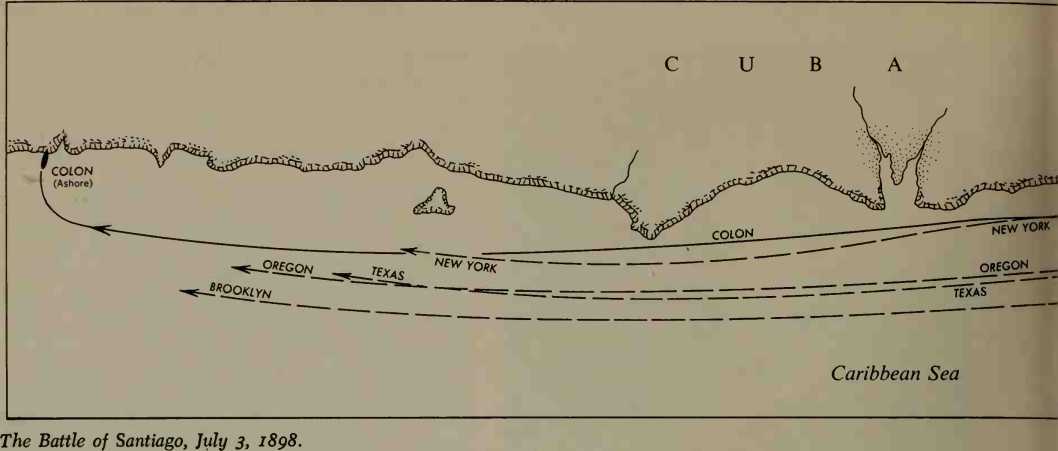

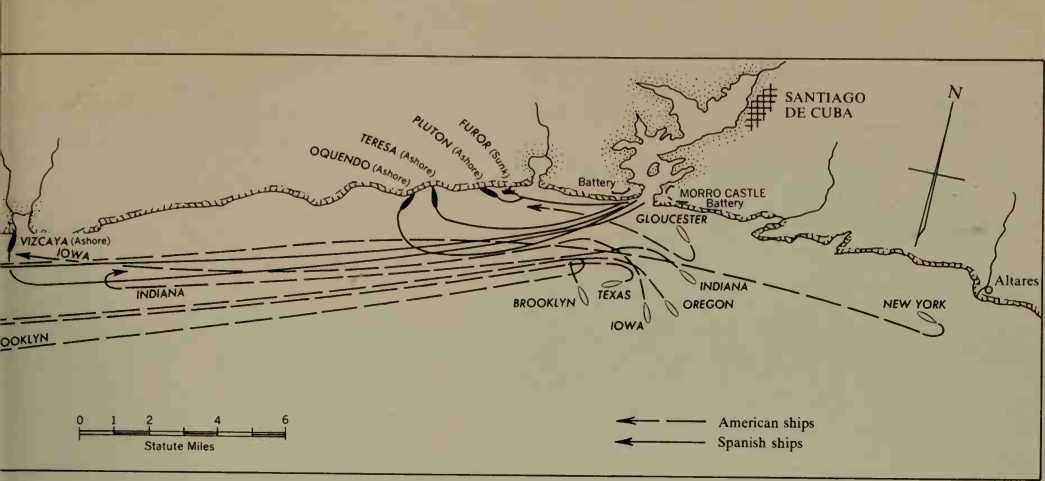

Cervera, ordered to get his ships out of Santiago harbor before they were captured or destroyed by the U. S. Army, chose this opportunity to sortie, leading the way out of the channel at 9:35 a. m. in the Maria

Teresa. The Iowa fired a warning shot, whereupon all the blockaders, opening fire, steamed toward the head of the emerging Spanish column. The Teresa turned west, hugging the shore and firing at the swift Brooklyn, Schley’s flagship. Crossing the Brooklyn’s bows, she broke out of the blockade. The Brooklyn, instead of immediately turning westward with the Teresa, turned east, on Schley’s orders, and made a complete loop. This clockwise revolution, never satisfactorily explained, not only cost the Brooklyn priceless time but very nearly brought her into collision with the Texas.

The battle quickly stretched out into a chase, with the Brooklyn and the Oregon forging out ahead of the other American vessels, and the New York far behind and vainly attempting to catch up. The two Spanish destroyers were almost blown out of the water by fire from the

Sampsons flagship New York.

Converted yacht Gloucester and by shells fired from the Indiana as she sped past. The Teresa, the Oquendo, and the Vizcaya were put out of action, not so much by direct American gunfire, which was less than remarkable, as by burning decks and other woodwork, with which they were too amply provided. All aflame, one after the other they turned toward shore and beached themselves. Only the Colon, swiftest of Cervera’s cruisers, continued in flight, speeding westward at 14 knots, hotly pursued by the Brooklyn and the Oregon, which gradually overtook her and began making hits. At that the Col6n, only slightly damaged, struck her colors and ran onto the beach. The Battle of Santiago was over. The Spaniards had lost 260 men, killed or drowned; some 1,800 others, including Cervera, were taken prisoner. American casualties were 1 man killed and 1 wounded.

Operations following the destruction of Spain’s Asiatic and Atlantic squadrons were militarily anticlimactic but far-reaching in their consequences. An American convoy bringing troops to occupy Manila made a bloodless capture of Spanish Guam, where the governor did not know that a war was in progress. Both Santiago and Manila capitulated after naval bombardments. With naval support, the U. S. Army took possession of the principal towns of Puerto Rico. The Navy next laid plans for a cruise against Spain itself. The Spaniards thereupon promptly sued for peace, relinquishing all claims to Cuba and ceding Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines to the United States. Cuba granted the United States a permanent naval base at Guantanamo Bay.

The gross errors made by the U. S. Army and Navy were more than offset by the far greater mistakes made by the armed forces of Spain. “We cannot expect ever again,” warned Mahan, “to have an enemy so entirely inapt as Spain showed herself to be.” Despite the flaws in the American performance, the war marked a turning point for the American people. The United States emerged as a major world power, and Americans thenceforth participated more generally in international affairs. More ominously, the accession of Guam and the Philippines projected American concerns into the area of interest of another expanding sea-power—Japan.

THE UNITED STATES

BECOMES A NAVAL POWER

The year of the Spanish-American War, 1898, was the watershed of American naval, as well as foreign, policy. That year Congress authorized three 18-knot battleships and four 12-knot monitors. The monitors, obsolete when built, were the final gasp of the old passive coast-defense strategy. Every year thereafter until the end of World War I, at least one battleship was authorized—the sole exception being 1901, and that only because of congestion in the shipyards. The new naval policy and the acquisition of the Philippines prompted the United States in 1898, after long hesitation, to annex the Hawaiian Islands, chiefly for a naval base. The following year the United States annexed Wake Island and American Samoa. In the glow of pride in the Navy’s accomplishments during the war with Spain, Congress also authorized the expansion and complete rebuilding of the United States Naval Academy. Down came the old red-brick buildings, most dating back

The '‘Great White Fleet” entering San Francisco Bay, igo8.

To pre-Civil War times; up went sparkling new French Renaissance-style buildings of granite and gray brick, including Bancroft Hall, the world’s largest dormitory.

The new ship construction, acquisition of bases, and building reflected the acceptance by Congress of the pohcy that the United States should have a navy powerful enough to defeat the main naval force of any potential enemy. The widely accepted national goal was to acquire a navy second only to that of Great Britain, which was no longer considered a potential enemy but a nation closely tied to the United States by a growing community of interests. America’s chief rivals in the new era were Germany, which was challenging British naval supremacy with an ambitious ship-construction program, and Japan, which by destroying Russia’s fleets in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05, had established a world position as a first-rate sea power.

Theodore Roosevelt, who, as Assistant Secretary of the Navy and as Vice President, had campaigned for the capital-ship policy, presided over its implementation from 1901 to 1909 as President. In a gesture of pride and muscle flexing, he sent his 16 first-line battleships, the “Great White Fleet,” on an unprecedented 14-month voyage around the world. It was a triumphant feat of shiphandling, but the British took the edge off

Roosevelt’s display of strength and skill. On the eve of the fleet’s departure from Hampton Roads, at the end of 1907, they revealed the characteristics of their new Dreadnought, which rendered every other battleship in the world obsolete.

World History

World History