In December 1780, Nathaniel Greene took command of the Continental Army in the South. Greene, a Quaker, had left his pacifist beliefs behind to fight in the Revolution. Now George Washington was counting on him to save that Revolution from being extinguished.

Greene Takes Command. Though he had fought

Alongside Washington in many battles, Greene was not anxious for command. Now, into his hands fell an army that was, in his own words, "wretched beyond description.” The ragged Southern troops numbered only 3,000 and had scant food or supplies. The British General Lord Cornwallis, on the other hand, had 4,000 experienced and disciplined troops ready and eager to grind the Americans into the ground.

Against all rules of warfare, Greene promptly divided his small force. He knew that Cornwallis could not chase one half without risking being attacked from the other. Greene dispatched 600 of his men west under the direction of the hard-fighting, rum-swilling Daniel Morgan. Morgan’s crack riflemen had been key to the American victory at Saratoga.

Cornwallis, in turn, divided his own force, sending half of it in pursuit of Morgan. Commanding these troops was Banastre Tarleton, whose name was infamous throughout the South. It was Tarleton who refused to allow Americans to surrender after Charleston, personally cutting down a soldier who raised the white flag and overseeing the slaughter of men who had laid down their arms. When Nathaniel Greene received word that Tarleton was on Morgan’s trail, he sent him a message. "Colonel Tarleton is said to be on his way to pay you a visit. I doubt not but he will have a decent reception.”

Hannah’s COWPENS. Morgan had a reception in mind, all right. He and his men had gathered near the border between the Carolinas at a place called Hannah’s Cowpens. With their backs to the river and no place to go, Morgan knew his men would fight hard. Still, he was aware that many of them were inexperienced militia. These men weren’t part of the Continental Army. They were defending their homesteads. Most couldn’t be expected to stand and shoot for long.

Morgan knew how to get the best from the motley group he commanded. As the British approached, he assembled his troops in three lines. Up front he put a row of his own sharpshooters, men who could pick off British officers at a distance. Behind them he put a line of the green militiamen, assuring them that they only

In 1780, toward the end of the Revolution, a British fleet with 1,200 troops sailed up Virginia’s James River and took Richmond with little resistance. The most shocking detail about the British raid was its commander—the American, Benedict Arnold.

Arnold was one of the Revolution’s most passionate Patriots and a superb general. Early in the war he had led an epic march of nearly 400 miles through the Maine wilderness into Canada. His daring but failed attack on Quebec

During a blizzard nearly cost the general his left leg. The wounded Arnold had to drag himself bleeding more than a mile back to his lines. He did not retire but went on to be a key figure in the American victory at Saratoga.

Had the Revolution ended earlier, or had Arnold died at Quebec, he would be standing proudly by W/ashington’s side in U. S. history books. Instead Arnold’s name is pure mud. Arnold’s real problem was not lack of belief in the revolutionary cause. It was greed. Like many other Patriots, Arnold had used his own money to finance his expeditions. Members of Congress—not generally fond of Arnold—refused to reimburse his expenses or to raise his salary, even when George Washington himself pleaded Arnold’s case. Arnold’s lifestyle was lavish. As he slipped increasingly into debt he began war profiteer

Ing-dealing in goods that were in short supply. The trade was illegal, and Congress censured him. Arnold reacted furiously to the criticism, having, as he said, “made every sacrifice of fortune and blood, and become a cripple in the service of my country.”

But Arnold did more than complain; he began to conspire. He agreed to turn over the plans of his new command. West Point, in return for a generalship in the British Army. Though Arnold’s treachery was soon discovered, he managed to escape to a British vessel.

Months later, when Arnold captured Richmond, the unrecognized general asked Virginians what they would do if fhey ever caught up to the infamous Benedict. One local replied that he would cut off Arnold’s left leg (wounded in Quebec) and bury it with full military honors. The rest of him he would hang.

_ bAA WJtUM .JHH '.SB, (

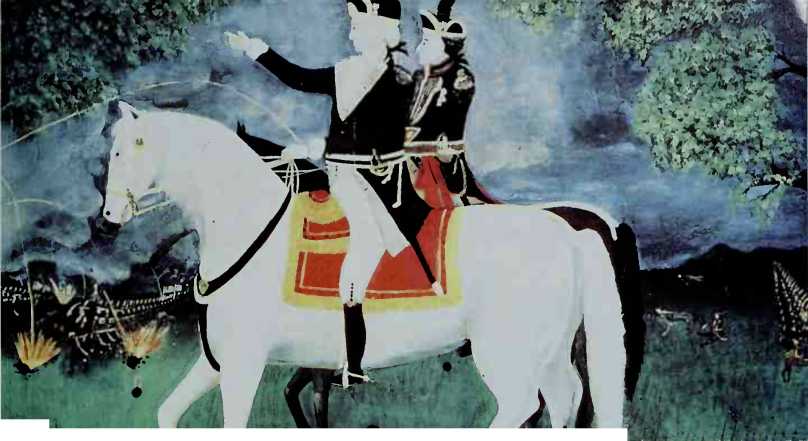

Washington and Lafayette at Yorktown. The French-American alliance had trapped Cornwallis’ British army.

Needed to fire two shots before running for cover. At a distance behind the militia, Morgan lined up a third row of disciplined Continental soldiers.

At dawn on the morning of January 17, Tarleton sent in cavalry scouts to see what the Americans were up to. Morgans sharpshooters promptly dumped them from their saddles. Tarleton then sent in the fii’st lines of his troops. As soon as the militia saw the redcoats, they fired their two rounds and broke for the American flanks. The British mistook the militias move for a retreat and pounded headlong toward the American lines. Before Tarleton’s troops knew what was happening, they ran smack into the ferocious Continentals.

—British Prime Minister Lord North

Tarleton, now a bit desperate, sent in his Highlanders, crack British troops. The Americans—hit hard—now fell back, and the British charged them once again. But as the redcoats approached the American lines, the Continentals turned suddenly around, firing a “sheet of flame” into their enemies’ faces.

The British broke ranks and ran. Within thirty minutes, over 900 men, 90 percent of Tarleton’s force, were killed or captured. Morgan and his soldiers sped over the Carolina border to rejoin their commander. Nathaniel Greene would much appreciate the reception Daniel Morgan had given Banastre Tarleton.

Yorktown. In mid-September, Cornwallis brought his troops up to Yorktown—a river port on the Chesapeake Bay—to await supplies from New York. Washington sent General Lafayette and 1,200 troops south to confront the British commander.

When Washington heard that a French fleet was en route to America, he planned a combined French and American attack on Yorktown. On September 28, 1781, more than 8,000 Americans and 7,800 French soldiers arrived in Yorktown to fight Cornwallis’ weary army of 7,000. The allies dug trenches, moved up their cannons, and before long had the British trapped against the York River. The French and American army then started shelling the outnumbered and despairing British.

Cornwallis had no options. On October 17, 1781, a British officer braved the bombardment and waved a white flag over his lines. Cornwallis’ stunned army was ready to suiTender if necessary.

Nobody realized that Yorktown was the end of the war. King George was prepared to continue the fight, but an annoyed and bankrupt Parliament put an end to it. A treaty was signed in Paris on September 3, 1783, formally ending the Revolutionary War.

World History

World History