Cont. iminj; two arinourcil divisions. All cflorts by the British to reach the men isolated at Arnhem were repelled after fierce clashes.

At the bridge, the paratroopers were pushed hack into a defensive

Air superiority during D-Day became the key to Allied success. While it was thought that the Luftwaffe would sent up some 900 aircraft to make 1,200 sorties on D-Day, in fact only 100 were made in daylight and a further 175 after dark. By contrast the RAF alone flew 5,656 sorties on D-Day, about 40 per cent of the total made by the Allies.

Allied aircraft dropped a total of 4,310 paratroops and lowed gliders containing 493 men, 17 guns, 44 Jeeps and 55 motorcycles without suffering harassment from enemy bombers.

As well as protecting troops and ships. Allied aircraft dropped 5,267 bombs against the coastal gun batteries.

The first German plane to fall victim on D-Day was a Ju 88, brought down by New Zealand Flying Officer Johnnie Moulton, one of 2,000 pilots in the Second Tactical Air Force who was in a Spitfire.

In the months which followed, three times as many bombs were dropped on Germany than in all the previous years.

Right: Troops taken by gliders into Arnhem In a bid to short-circuit the route to Berlin. The Britons had a grim late In store.

Of committing the ground troops to one hammer-blow into nortitern Germany, l-'isenhower favoured a fan-shaped attack instead.

‘Operation. Market Garden’ was designed to capture key bridges in Holland through which Allied troops could be funnelled into Germany. The US 101 St Airborne Division was charged with gaining land north of Eindhoven, the US 82nd Airborne Division was allocated two big bridges over the. Meuse and the Wall rivers, while the British 1st Airborne Division had to seize bridges over the lower Rhine at Arnhem.

The men were carried to their targets in a total of 1,068 aircraft and 478 gliders. While the Americans experienced considerable success on their fronts, the British met enormous German resistance en route to their target, just one battalion, the 2nd, reached the bridge at Arnbem. Soon after, they were cut off.

Unfortunately for the British paratroopers, the Germans picked Arnhem as a focal point of defence and reinforced their lines with troops, including an S. S Panzer corps

It took nine days for the men to establish an escape route across the Rhine

Margin. It took nine days for the men to establish an escape route across the Rhine, just 2,200 men got out from a force which began with a strength of 10,000. Montgomery’s plan to by-pass Germany’s defensive Siegfried line had failed. The thrust continued as before.

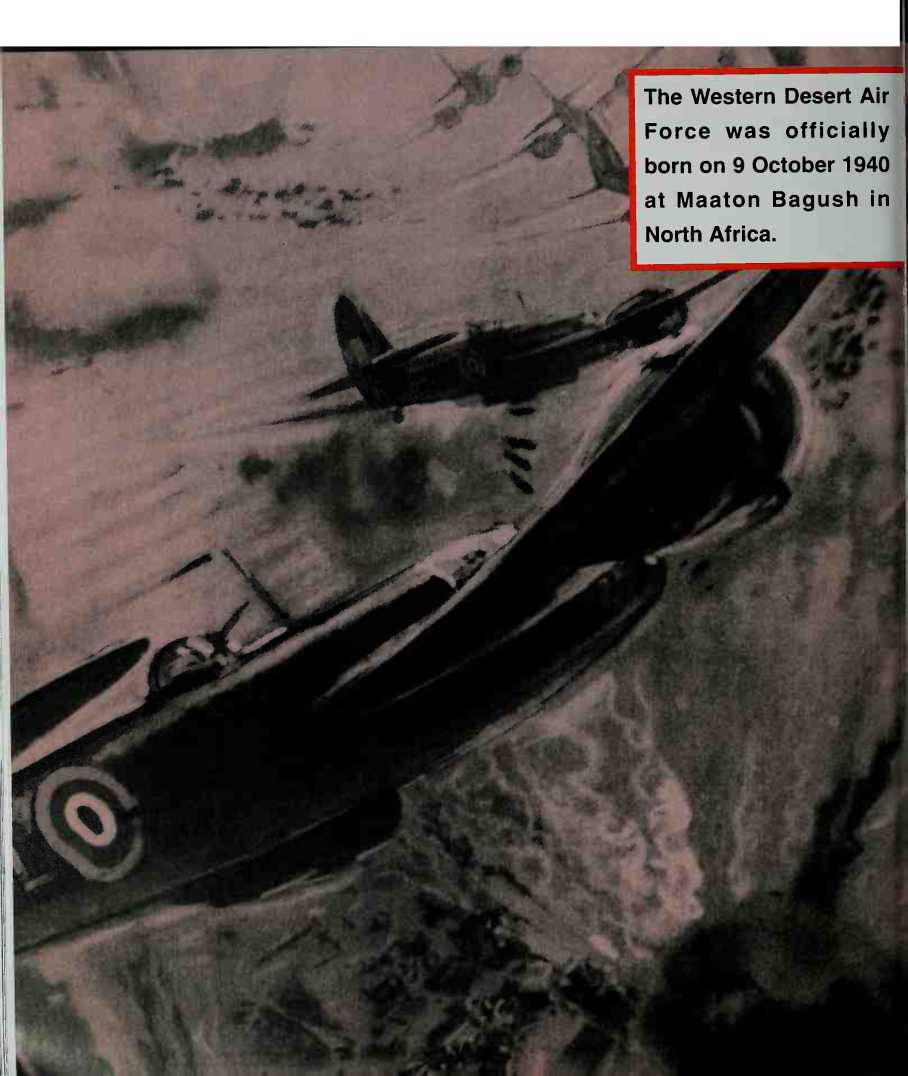

WINGS OVER THE DESERT

Here in the African desert, the theories of modern air warfare were established. For it was in North Africa that the principles of ‘partnership’ bervs-een air, sea and land forces were tried and tested for the first time, helping to put an end to decades of overt inter-service rivalry.

Co-operation of the kind enjoyed by air, sea and naval personnel among the Allies was unthinkable for their German and Italian counterparts, who not only fought a common enemy but were constantly embroiled in sniping against different factions on their own side. Indeed, there were plenty of hiccoughs along the way among the Allies with soldiers convinced the only worthwhile aeroplane was the one that flew protectively above their heads, regardless of the risk to the pilot and his inability to achieve results from that vulnerable spot.

The initial trials of tactical airborne operations were honed by the men of the Desert Air Force until they finally became adopted everywhere.

Unfortunately for the Italians, early promise was soon done down by the Desert Air Force

Lessons learned in the Desert Air Force now seem rudimentary and even naive. Yet aerial combat was still in its infancy when the war commenced. Fliers in World War I had the opportunity to make only elementary trials and errors. Little was done to advance the theory of warfare in the air after 1918 as most nations were concentrating on peace.

And until the conflict in the desert got underway, the Royal Air Force was from necessity concentrating primarily on defence.

To call it simply a Desert Air Force is to vastly over-simplify the case. The men who worked under its umbrella saw action in the skies above Egypt, Libya, East and West Africa, Greece, Yugoslavia, Palestine, Italy and other hot spots in the region.

This tremendous fighting force grew from an original nucleus of some 29 squadrons - a total of 600 aircraft. These were all that were available to Middle East commander Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Longmore when hostilities with Italy commenced in 1940. Included in this total were a goodly number of outdated biplanes and obsolete Blenheim bombers. That summer on the home front saw the Battle of Britain reach its momentous heights. So the chances of getting top-notch replacements were slim.

In addition, the airmen faced the same shortages that cursed the soldiers on the ground, those of water, fuel and spare parts to replace those worn by the inhospitable terrain.

Above: Mussolini believed his air force could win the skies over Africa. Left: Stalwart Beaufighters played a key role in the North African campaign.

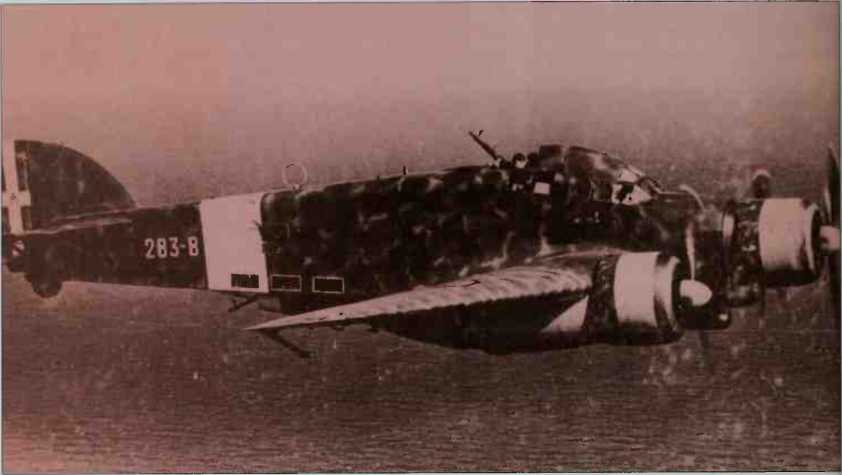

Against them was the might of the Regia Aeronautica, the Italian air force, which had proved itself already in the Spanish Civil War and Mussolini’s Ethiopian campaign in the mid-1930s. The Italians were flying home-produced planes like Capronis and Fiats. Unfortunately for the Italians, their early promise was soon done down by the Desert Air Force.

The Regia Aeronautica went into action for the first time on I I June 1940, with 35 Savoia-.Marchetti bombers attacking. Malta. Pitted against them were four Gloster Sea Gladiators, constituting the island’s only fighter defence force. By the end of the day, the Italians had launched seven attacks for no loss.

By way of response, 26 RAF Bristol Blenheims launched an attack against an Italian airfield in North Africa, eventually destroying 18 enemy aircraft on the ground.

Above: Despite their years of experience, Italian aircraft and pilots proved no match for the Desert Air Force.

There followed a number of skirmishes. Prime targets for the Italians were Malta, Gibraltar, the British base at Alexandria in Egypt and the British Mediterranean Fleet.

The action in Africa then forked, with General Graziani leading his contingent of Italians in the Western Desert against Wavell, while the Duke of Aosta led some 215,000 troops out of Italian East Africa and into a British dominion. To meet Graziani’s men were the British 7th Armoured Division, soon to be joined by the 6th Australian Division. Meanwhile, the 4th Indian Division was dispatched to meet the threat in East Africa.

It was in the East African campaign that vital steps towards an orchestrated plan for close air support were made. At the outset in October 1940, the Italians in East

Africa were a formidable enemy. Their spirits were high, their maturity in desert warfare a major advantage. But much of their buoyancy could be put down to the fact that they enjoyed air superiority. Italy had 14 bomber squadrons or gruppi in East Africa, and five supporting fighter gruppi. The over-stretched British forces, comprising nine squadrons, were happily reinforced by a further eight squadrons from South Africa, flying Hurricane aircraft.

Soon the battle to win supremacy of the skies began to swing in favour of the Allies

Soon, the battle to win supremacy in the skies began to swing in favour of the Allies. Both sides fought bitterly, both on land and in the air, for command of Keren, a fortified hill top in Eritrea. At the end of eight weeks, however, the Italians were turfed out of their stronghold and, by April 1941, a corner in the war of East Africa had been turned. As the campaign toiled on, the South African Air Force formed a first Close Support Flight to co-operate with ground troops, achieving a good measure of success.

After the battle of Keren, one British observer noted five lessons to be learned. They were: the need for transport planes; the need for supplies to be dropped by air (which was to prove crucial in the jungle wars of Burma and the Pacific); the advantage lent by long-range fighters which could destroy the enemy’s aircraft before they lifted off; the need for Red Cross air ambulances to evacuate the wounded; and the preference for dive bombers.

World History

World History