Operation Barbarossa was launched on 22 June 1941. At 0400 that Sunday morning German forces crossed the Russian frontier. In the north an army group under the command of General Leeb crossed from East Prussia into Lithuania. In the south a second army group under the command of General Rundstedt moved from Lwow toward Galicia. In the center, a third group under the command of General Bock moved across northern Poland toward the Russian border. The long awaited invasion of the Soviet Union had begun.

As Hitler had expected, the Ru. ssians were unprepared for the German attack. Although units of the Red Army had been moved into the Baltic states and the western provinces just weeks before the attack, they were not deployed systematically. Such forces as there were on the German frontier were thinly spread over a large area. When the three German army groups initiated action, these forward units were easily overrun and could not be rescued, due to the distance between them and the rest of the Russian forces, scattered an)'where from 60 to 380 miles away in the hinterland. With little effective resistance from the Red Army, German forces were able to race eastward at a pace never dreamt of by Hitler and Paulus. Even the most whole-hearted advocates of the operation were stunned at the speed and facility of the Wehrmacht’s advance.

Germany’s military leaders had reason to be impressed by the results of the first day’s activities against the Soviets. Within twenty-four hours,

10,000 prisoners had been taken, the Luftwaffe had destroyed or disabled 1200 Russian aircraft, and German mechanized units had moved fifty miles into Russian controlled areas of Poland. It was an unmitigated triumph for the Germans and in succeeding days they were able to press on further, repeating the feat of the first day. By the beginning of July few in Berlin doubted that Hitler would feast in Moscow at Christmas.

Success posed certain problems for Hitler’s lieutenants, who were divided over whether to alter the original plan ofinvasion and race toward Moscow and other interior points, or maintain the original program which called for a slower eastward advance and the encirclement of Russian armies in the western part of the Soviet Union. Tank experts, like Guderian, wanted to take advantage of the momentum to rush eastward, driving as deep as space and time would permit, thus repeating in Russia the program which had been so successful in France. More conservative strategists urged restraint. They advised Hitler to use tank forces in support of infantry action until the bulk of Russia’s western armies were defeated, promising the capture of tens of thousands of prisoners when the encirclement of Soviet forces was completed. To the chagrin of the tank experts. Hitler chose to accept the more orthodox approach.

The decision to abide by the original plan of invasion proved to be of greater benefit to the Red Army than to the Wehrmacht because it allowed the Russians to finally respond to the invasion while German forces were still tied up on the fringe of the Soviet Union, far removed from the important urban centers and rear grouping areas of the Russian army. Although the Germans would exact a heavy price in men and material from Russian forces, Stalin could rally the nation while forward units of the Red Army tenaciously held out against overwhelming odds. Losses would be heavy by orthodox standards, but in the end Germany’s resources would be strained long before Russia’s were depleted.

On ;5 July, after a silence of nearly two weeks, Stalin spoke to his nation. All, Soiet citizens were called upon to defend their motherland and make whatever saerifiee was necessary to defeat fascist aggression. If the Red Army was forced to retreat, nothing of value would be left for the (Jermans; the Soviet citizenry would (nirsue the same scorched earth policy against the in adcr as their forefathers had used a century before. Hitler would reap no easy v ictory in Russia.

.Stalin’s refusal to succumb in the face of adversity led him to risk losses that other men would nev er have considered. If Soviet citizens were prepared to sacrifice themselves in the defense of mother Russia, members of the Red Army could be asked to do no less. I'ield commanders were instructed to hold positions regardless of cost, so that even when surrounded and clearly defeated, Russian forces continued to fight on, their stubborn resistance slowly blunting the German advance. I he proverbial doggedness of the. Slav was well illustrated by the Russian conscripts, who seemed to have ‘an illimitable capacity for obedience and endurance’; the Germans might outflank ;ind outmancuver their adversaries, but they would not outfight them.

'I his stilf opposition, and the changing weather, began to have a serious effect on the morale of the German troops; although the Wehrmacht had made great headway during the first two weeks of the Russian campaign, the pace and progress of the invasion were gradually slowed down. In the north Leeb’s army group had raced through the Baltic states but was stalled before Leningrad. In the south Rundstedt was encountering particularly heavy resistance from the. Soviet Fifth /my and had tcj call on Bock’s central armv grouj) for reinforcement. "Fhe diversion of elements of Bock’s army to the south cri()pled the advance on Moscow by depriving it of armored and mechanized units. 'I’his was most unfortunate, since it was Bock’s group which had the greatest chance for an early victory. Fhe capture of the Soviet capital would have paralyzed Russian communications and severely alfceted Russian morale, but for the Fuehrer, the most important task of the Wehrmacht was to conquer the

Left lop: German troops hit (lie dill as a Russian shell explodes m froiil of them. Left center: The lirsi raids of the laiftwaffe on Russian lernlois went almost iino|)posed.

Left: Wounded memliers of Russi. i’s suit ide s(|u. ids,

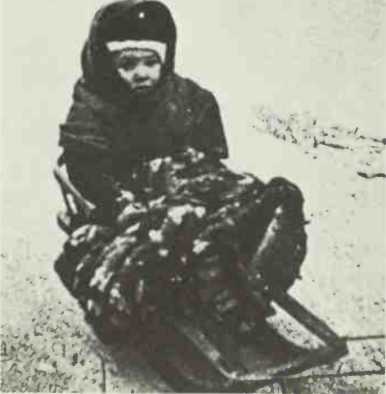

I lies vseie purposeh left liehind when the Russians withdrew in order to h. imper the Na/i ads. line, f ew (.ime out. ills e Right: When winter set in sulFeiing tor (istli. ins and soldters. iliki w. is sesere I his ( htid w. is. imoiig (he m. ins es. it ti. iled Irom I. eningr. id prior to ihe siege

Previous page: The guncrew of a German Panzerjager unit in action against Soviet armor.

Right: Units on both sides were virtually immobilized by the end of November. Far right: Siberian reinforcements move up to bolster the sagging defenses around Moscow.

Opposite center; Cavalry was able to move across the icy terrain which brought Panzer di isions to a standstill. Opposite hottom: Russian troops counterattack to approach the great monastery at .Mozhaisk.

Crimea and the Donetz basin, thereby severing Russia’s pipelines from the Caucasus. Only after this was accomplished could the assault on Moscow be resumed with full force.

Hitler’s diversion of resources to the southern sector proved even more fortuitous to the Russians than his refusal to alter the original invasion plan. Had Bock pressed on toward Moscow, there is little doubt that the city would have fallen into German hands by the end of the summer, but with the movement of armored units south to aid Rundstedt, it was doubtful whether the offensive in the central area could be resumed before the onset of autumn; by that time weather conditions would make such a drive increasingly difficult and Russian reserves from the far eastern provinces would be mobilized and ready to defend the Soviet capital. The specter of being trapped in front of Moscow at the onset of winter was not a pleasant one for the German field commanders and their superiors on the General Staff, and it is not surprising, therefore, that most senior German officers favored disregarding the situation on the southern front and pressing on toward Moscow at full speed and with full strength. If Hitler viewed Moscow as ‘a geographical expression only,’ his commanding officers were of another mind. So serious was the breach over this matter that Brauchitsch and Haider were prepared to tender their resignations if the advance on Moscow was not continued, but even this threat was not sufficient to change Hitler’s mind. In the end, Brauchitsch and Haider chose not to resign, apparently concluding that such a move would serve no useful purpose.

The argument over Rundstedt’s reinforcement wasted five weeks; it was not until 21 August that the matter was finally resolved, and by then conditions were considerably more unsatisfactory for a German advance than they had been at the beginning of the summer. Rains had washed out many secondary roads and primary roads were clogged with men and equipment. The advent of cold weather was near and the movement of supplies was becoming increasingly more difficult. Resistance was stiff and victory was still far from sight. Although a triumph of sorts would be achieved in the south, its cost would be far more than the net gain it yielded.

World History

World History