Born to Persian immigrants in the Afghan city of Kandahar, Princess Mihr un-nisa (meer oon-NEE-sah), known to history as Nur Jahan, or “Light of the World,” married the Mughal emperor Jahangir (jah-hahn-GEER) in 1611, at the age of thirty-four. As the emperor increasingly turned his attention to science and the arts, as well as to his addictions to wine and opium, Nur Jahan increasingly assumed the ruler’s duties throughout the last decade of her husband’s life, which ended in 1627. She had coins struck in her name, and most importantly, she made certain that a daughter from an earlier marriage and her brother’s daughter both wed likely heirs to the Mughal throne.

As her husband withdrew from worldly affairs, Nur Jahan actively engaged them. After a visit from the English ambassador in 1613, she developed a keen interest in European manufactures, especially quality textiles. She established domestic industries in cloth manufacture and jewelry making and developed an export trade in indigo dye. Indigo from her farms was shipped to Portuguese and English trading forts along India’s west coast, then sent to Lisbon, London, Antwerp, and beyond.

In 1614, Nur Jahan arranged for her niece, Arjumand Banu Begum (AHR-joo-mond bah-noo BEH-goom), to marry Jahangir’s favorite son, Prince Khurram, known after he became emperor as Shah Jahan. Arjumand Banu Begum, who took the title Mumtaz Mahal,

Trading Cities and Inland Networks: East Africa

How did Swahili Coast traders link the East African interior to the Indian Ocean basin?

Trade and Empire in South Asia

What factors account for the fall of Vijayanagara and the rise of the Mughals?

European Interlopers

What factors enabled Europeans to take over key Indian Ocean trade networks?

COUNTERPOINT:

Aceh: Fighting Back in Southeast Asia

Why was the tiny sultanate of Aceh able to hold out against European interlopers in early modern times?

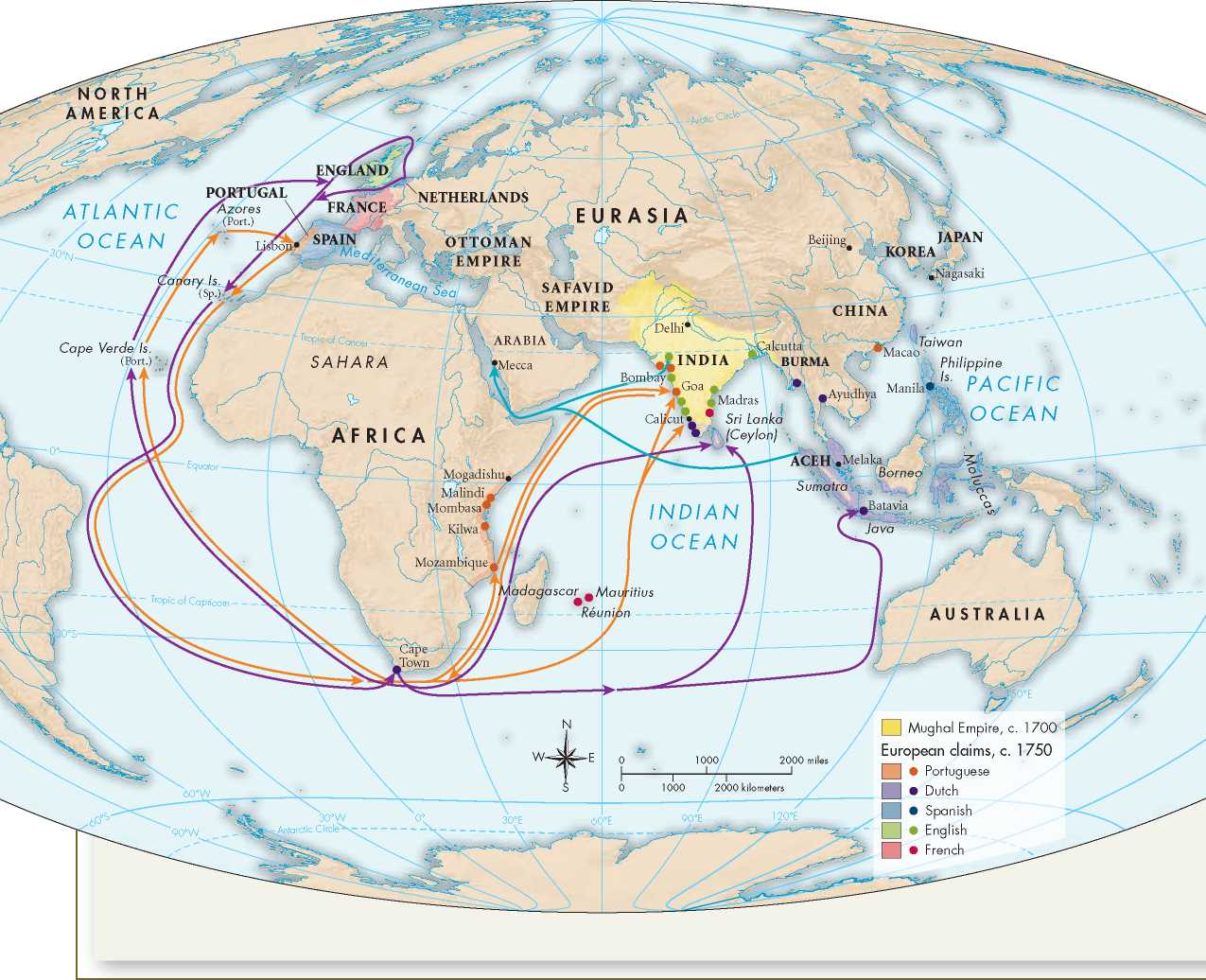

For centuries before the rise of the Atlantic system (see Chapter 17), the vast Indian Ocean basin thrived as a religious and commercial crossroads. Powered by the annual monsoon wind cycle, traders, mainly Muslim, developed a flourishing commerce over thousands of miles in such luxury goods as spices, gems, and precious metals. The network included the trading enclaves of East Africa and Arabia and the many ports of South and Southeast Asia. Ideas, religious traditions— notably Islam—and pilgrimages moved along the same routes. Throughout the Indian Ocean basin, there was also a trade in enslaved laborers, mostly war captives, including many non-Africans, but this trade grew mostly after the rise of plantation agriculture in the later eighteenth century. The vast majority of the region’s many millions of inhabitants were peasant farmers, many of them dependent on wet-rice agriculture.

At the dawn of the early modern period, Hindu kingdoms still flourished in southern India and parts of island Southeast Asia, but these were on the wane. By contrast, some Muslim kingdoms began an expansive phase. After 1500, a key factor in changes throughout the Indian Ocean basin was the introduction of gunpowder weapons from Europe.

1336-1565 Vijayanagara kingdom in southern India

¦ 1498 Vasco da Gama reaches India

¦ 1511 Portuguese conquest of Melaka

1526 Battle of Panipat led by Mughal emperor Babur onquest of Melaka 1517 Portuguese establish fort in Sri Lanka (Ceylon)

1605-1627 Reign of Mughal emperor Jahangir

¦ 1600 English East India Company founded in London

World History

World History