The only good Chechen is a dead Chechen.

- Attributed to General Alexei Yermolov, 1812

Traditionally, Russian attitudes towards the Chechens have been complex, a mix of fear, hatred and respect. In the main, the Russians have considered the gortsy, the 'mountaineers' as they sometimes call the peoples of the North Caucasus, to be generally untrustworthy, wily yet primitive. However, the Chechens assumed a special place in the 19th-century Russian idea of the Caucasus, sometimes the noble savage, often just the savage. Mikhail Lermontov's Cossack Lullaby, for example, includes the lines 'The Terek runs over its rocky bed./And splashes its dark wave;/A sly brigand crawls along the bank;/Sharpening his dagger' while in the song the Cossack mother reassures her child that 'your father is an old warrior; hardened in battle'. There was something different, something alarming about the Chechens.

To a considerable extent this reflects the tenacity, skill and ferocity with which they have fought against Russian imperialism since the earliest contacts.

Although Cossack communities, seeking an independent life outside Tsarist control, settled in the North Caucasus as far back as the 16th century, it was really only in the 18th century that the Chechens and the Russian state encountered each other. There were skirmishes during Peter the Great's 1722-23 Caucasus campaign against Safavid Iran that showed that the Chechens in their home forests were not to be taken lightly, but it was the struggle against Sheikh Mansur (1732-94) which began in 1784 that truly alerted the Russians to the threat they faced. A Chechen Muslim imam, or religious leader, educated in the Sufi tradition, Mansur was angered by the survival of so many preIslamic traditions within Chechnya and campaigned for the universal adoption of sharia Islamic law over the adat. He declared a holy war - jihad or, in the North Caucasus, gazavat - initially against 'corrupt Muslims' who did not recognize the primary of sharia and, coincidentally, his own authority.

This was an essentially domestic issue, but Mansur's message became increasingly popular across the North Caucasus as a whole and followers of other ethnic groups began flocking to his cause. When the Russian authorities heard that he was

Tsar Peter the Great (1672-1725), depicted in an 1838 work by Paul Delaroche (1797-1856). Although Peter the Great is best known for building St Petersburg and his European military adventures, his Azov campaigns against the Ottoman Empire (1695-96) continued a drift to the south in Russian imperial expansion that would bring them into collision with the Chechens. (Public domain)

Planning to invade neighbouring Kabardia to spread his word, and even opening negotiations with the Ottoman Empire, they became alarmed. The Ottomans were the Russians' main rivals along their southwestern flank, and Mansur's holy war could easily and quickly be turned against Orthodox Christian Russia. Contemptuous of Mansur's 'scoundrels' and 'ragamuffins', the Russians sent the Astrakhan Regiment into Chechnya, to Mansur's home village of Aldy. Finding it empty, they put it to the torch, handing Mansur perfect grounds to declare gazavat against the Russians. Ambushed by the Chechens at the Sunzha River crossing as they marched back, the Russians were massacred: up to 600 were killed, 100 captured and the regiment disintegrated, individuals and small groups hunted down as they tried to flee through the woods.

Buoyed by this success, Mansur gathered a force of up to 12,000 fighters from across the North Caucasus, although Chechens were the largest contingent. His skills were as charismatic leader rather than strategist, though, and Mansur made the mistake of crossing into Russian territory and trying to take the fortress of Kizlyar. Fighting the Russian Army on its own terms and in its own territory, Mansur's forces were routed. Although Mansur would remain active until his capture in 1791, whenever he took the field against the Russians, he lost. Even so, he had demonstrated that the Chechens could be formidable when united against a foreign enemy and fighting their own kind of war.

Hitherto, though, Chechnya had been considered something of an irrelevance, a land rich only in troublesome locals. The real prize was Georgia to the south, and the real enemies were Safavid Iran and the Ottomans. When Georgia was annexed in 1801, secure routes to Imperial Russia's newest possession began to matter. Once Russia found itself at war with both Iran (1804-13) and the Ottoman Empire (1807-09), then the need to shore up the Caucasus flank meant that St Petersburg finally decided it was time to extend its rule in the North Caucasus.

The chosen instrument was General Alexei Yermolov, an artilleryman who had distinguished himself during the war with Napoleon and who was made viceroy of the Caucasus. He set out to subjugate the highlands by a policy of deliberate, methodical brutality. His strategy was to build fortified bases and settlements across the region, to bring in Cossack soldier-settlers and to respond to risings and provocations with savage reprisals. Infamously, he affirmed 'I desire that the terror of my name shall guard our frontiers more potently than chains or fortresses.'

Yermolov was especially wary of the Chechens, whom he considered 'a bold and dangerous people'. He founded the fortress of Grozny in 1818 - the name means 'Dread' - as a base from which to control the central lowlands. His aim was to pen the Chechens in the mountains, clearing the fertile lowlands between the Terek and Sunzha rivers for Cossack settlers. They in turn would cut down the forests that gave the Chechens such an advantage. In 1821, the Chechens held a gathering of the teips to unite against the Russians; Yermolov

This portrait of General Alexei Yermolov (1777-1861), painted by British artist George Dawe (1781-1829) while Yermolov was still viceroy of the Caucasus, captures the man’s determination and obdurate ferocity (Public domain)

Responded with a campaign to drive the Chechens into the highlands with fire, shot and sword. Even so, the Chechens were beleaguered but not beaten. In a sign of things to come, terrorism and assassination began to supplement raids in their tactical repertoire. In 1825 two of Yermolov's most notorious officers, Lieutenant-General Dmitri Lissanievich and Major-General Nikolai Grekov, died when an imam, brought in for interrogation, produced a hidden dagger and stabbed them both. The Russians executed 300 Chechens in reprisal.

In 1827, Yermolov was recalled and removed, the victim of court politics rather than as a result of any discomfort about his methods. His successors followed broadly similar policies, albeit with less ruthless enthusiasm. However, the next phase of the Russo-Chechen conflict would instead be

Recent accounts of the storming of the small, stone-hewn mountain villages, once the artillery bombardment had lifted and it became a question of close-quarter combat, are uncannily reminiscent of tales of taking fiercely held Chechen villages in the 19th century including the 1832 assault on Gimri represented in this 1891 work by Franz Roubaud (1856-1928). (Public domain) initiated and defined by the 'mountaineers', specifically Imam Shamil (1797-1871), a Dagestani who raised the North Caucasus in rebellion and who remains a cultural hero for the Chechens to this day.

Shamil was a fighter as well as a religious figure, the de facto moral leader of the scattered 'mountaineer' resistance movement from 1834. At first, he tried to come to terms with the Russians, offering to accept their sovereignty and end raids on the lowlands, in return for a degree of cultural and legal autonomy. Major-General Grigory Rosen - who in 1832 had led a force of almost 20,000 troops across Chechnya, systematically burning crops and villages - rejected any thought of compromise. In part, this was precisely because the Russians feared the Chechens. In 1832, one officer admitted that 'amidst their forests and mountains, no troops in the world could afford to despise them' as they were 'good shots, fiercely brave [and] intelligent in military affairs'. Lieutenant-General Alexei Vel'yaminov, Yermolov's chief of staff, noted that they were 'very superior in many ways both to our regular cavalry and the Cossacks. They are all but born on horseback.'

The Russians, thinking themselves on the verge of victory, simply increased the pressure. In 1839, Shamil only barely managed to escape when besieged for 80 days at Akhoulgo. The Russians took some 3,000 casualties before eventually storming this fortified village. However, they overplayed their hand and tried to implement a range of policies, meant to quash Chechen spirits once and for all. They only managed to rekindle the rising. Pristavy, government inspectors recruited from local collaborators, were given wider powers, which they typically used to persecute and plunder. Lowland Chechens were forbidden to have any contact with their upland relatives - or even sell them grain, one of their main sources of income. Then the

Russians tried to disarm the Chechens, confiscating weapons which were seen as the main accoutrements of manhood and were often cherished family heirlooms.

Shamil combined Mansur's charisma with rather greater military acumen. He raised the North Caucasus in a rebellion characterized by guerrilla attacks rather than set-piece battles in which Tsarist discipline and firepower could prevail. In 1841, General Yevgeni Golovin - who had previously quelled a Polish uprising - warned that the Russians had 'never had in the Caucasus an enemy so savage and dangerous as Shamil'. Ultimately, though, he would fail. It was perhaps inevitable when set against the whole weight of the Russian Empire. After the end of the Crimean War in 1856, the

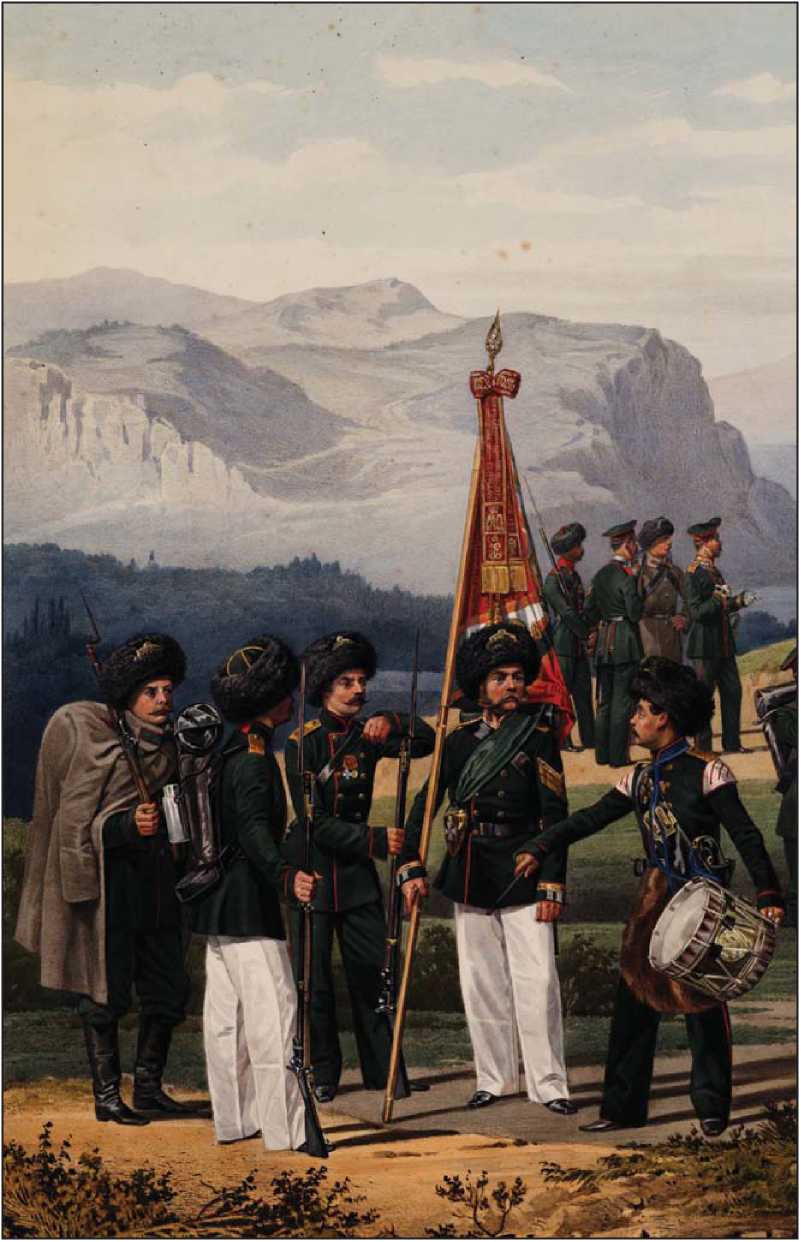

Left: Detail from Infanterie de I’Armee de Caucase (1867), a hand-coloured lithocolour plate from an original by Piratski and Gubaryev, showing Russian and Cossack infantry officers and men from the Army of the Caucasus. Service in the Army was deemed one of the more arduous and dangerous postings in the Tsarist military. (Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

Below: This undated photograph from the early Soviet era shows Muslim women crowding a street in the Caucasus region to listen to a Communist speaker delivering a speech on Soviet doctrine. This was presumably staged for the camera, as the Bolsheviks had relatively limited success in spreading their message in the region. (© Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS)

Russians were able to deploy fully 200,000 troops to the Caucasus. In 1859, Chechnya was formally annexed to the Russian Empire and Shamil was captured, whereupon he was treated as an honoured prisoner. He was brought to St Petersburg for an audience with Tsar Alexander II before being placed in luxurious detention first in Kaluga and then Kiev. In 1869 he was even permitted to make the hajj pilgrimage to Mecca and he died in Medina in 1871. In an irony of history, while two of his four sons continued to fight in the Caucasus, the other two would become officers in the Russian military.

World History

World History