Interest in the Antiquity of man—Connected with the Glacial Age—The Subject Difficult—Proofs of a Glacial Age—State of Greenland to-day—The Terminal Moraine—Appearance of the North Atlantic—Interglacial Age—Causes of the Glacial Age—Croll's Theory—Geographical causes—The two theories not Antagonistic—The date of the Glacial Age—Probable length of the Paleolithic Age—Time since the close of the Glacial Age—Summary of results.

WE have already remarked, geological periods give us no insight as to the actual passage of years. To say that man lived in the Glacial Age, and that we have some faint traces of his presence in still earlier periods, after all conveys to our minds only vague ideas of a far-away time. The more a geologist studies the structure of the earth, the more impressed is he with the magnitude of the time that must have passed since "The Beginning." At present, however, there are no means known of accurately measuring the time that has passed. It is just as well that it is so, since, were it known, the human mind would be utterly incapable of comprehending it. But as to the antiquity of man, it is but natural that we should seek more particularly to solve the problem and express our answer in some term of years.

Now, we have seen that the question of the antiquity of man is intimately connected with that of the Glacial Age. That is to say, the relics of man as far as we know them in Europe, are found under such circumstances that we feel confident they are not far removed from the period of cold. For it will be found that those conservative scholars who do not think that man preceded the Glacial Age, or inhabited Europe during the long course of years included in that period, do think he came into Europe as soon as it passed away. So, in any case, if we can determine the date of the Glacial Age, we shall have made a most important step in advance in solving the problem of the antiquity of man himself. So it seems to us best to go over the subject of the Glacial Age again, and see what conclusions some of our best thinkers have come to as to its cause, when it occurred, and other matters in relation to it.

It is best to state frankly at the outset that this topic is one of the great battle-grounds of science to-day, and that there are as yet but few points well settled in regard to it. One needs but attempt to read the literature on this subject to become quickly impressed with the necessity of making haste slowly in forming any conclusions. He must invoke the aid of the astronomer, geologist, physical-geographer, and physicist. Yet we must not suppose that questions relating to the Glacial Age are so abstruse that they are of interest only to the scholar. On the contrary, all ought to be interested in them. They open up one of the most wonderful chapters in the history of the world. They recall from the past a picture of ice-bound coasts and countries groaning under icy loads, where now are harbors enlivened by the commerce of the world, or ripening fields attesting the vivifying influence of a genial sun. Let us, therefore, follow after the leaders in thought. When we come to where they can not agree we can at least see what both sides have to say.

Somewhat at the risk of repetition, we will try and impress on our readers a sense of the reality and severity of the Glacial Age. There is danger in regarding this as simply a convenient theory that geologists have originated to explain some puzzling facts, that it is not very well founded, and is liable to give way any day to some more ingenious explanation. On the contrary, this whole matter has been worked out by very careful scholars. "There is, perhaps, no great conclusion in any science which rests upon a surer foundation than this, and if we are to be guided by our reason at all in deducting the unknown from the known, the past from the present, we can not refuse our assent to the reality of the Glacial Age of the Northern Hemisphere in all its more important features.2 At the present day glaciers do exist in several places on the earth. They are found in the Alps and the mountains of Norway, and the Caucasus, in Europe. The Himalaya mountains support immense glaciers in Asia; and in America a few still linger in the more inaccessible heights of the Sierra Nevada. It is from a study of these glaciers, mainly however, those of the Alps, that geologists have been enabled to explain the true meaning of certain formations they find in both Europe and America, that go by the name of drift.

When in an Alpine valley we come upon a glacier, filling it from side to side, there will be noticed upon both sides a long train of rock, drift, and other débris that have fallen down upon its surface from the mountain sides. If two of these ice-rivers unite to form one glacier, two of these trains will then be borne along in the middle of the resulting glacier. As this glacier continues down the valley, it at length reaches a point where a further advance is rendered impossible by the increased temperature melting the ice as fast as it advances. At this point the train of rocks and dirt are dumped, and of course form great mounds, called moraines. The glacier at times shrinks back on its rocky bed and allows explorers to examine it.

In such cases they find the rocks smoothed and polished, but here and there marked with long grooves and striæ. These points are learned from an examination of existing glaciers. Further down the valley, where now the glaciers never extend, are seen very distinctly the same signs. There are the same moraines, striated rocks, and bowlders that have evidently traveled from their home up the valley. The only explanation possible in this case is that once the glaciers extended to that point in the valley.

It required a person who was perfectly familiar with the behavior of Alpine glaciers, and knew exactly what marks they left behind in their passage, to point out the proofs of their former presence in Northern Europe and America, where it seems almost impossible to believe they existed. Such a man was Louis Agassiz, the eminent naturalist. Born and educated in Switzerland, he spent nine years in researches among the glaciers of the mountains of his native country. He proved the former wide extension of the glaciers of Switzerland. With these results before them, geologists were not long in showing that there had once been glacial ice over a large part of Europe and North America.

The proofs in this case are almost exactly the same as those used to show that the ancient glaciers of Switzerland were once larger than now. But as the great glaciers of the glacial age were many times larger than any thing we know of at the present day, there were of course different results produced.

For instance, the water circulating under Alpine glaciers is enabled to wash out and carry away the mass of pulverized rock and dirt ground along underneath the ice. But when the glaciers covered such an enormous extent of country as they did in the Glacial Age, the water could not sweep away this detritus, and so great beds of gravel, sand, and clay would be formed over a large extent of country. But to go over the entire ground would require volumes; it is sufficient to give the results.

The interior of Greenland to-day is covered by one vast sea of ice. Explorers have traversed its surface for many miles; not a plant, or stone, or patch of earth is to be seen. In the Winter it is a snow-swept waste. In the Summer streams of ice-cold water flow over its surface, penetrating here and there by crevasses to unknown depths. This great glacier is some twelve hundred miles long, by four hundred in width.3 Vast as it is, it is utterly insignificant as compared with the great continental glacier that geologists assure us once held in its grasp the larger portion of North America.

The conclusions of some of our best scholars on this subject are so opposed to all that we would think possible, according to the present climate and surroundings, that they seem at first incredible, and yet they have been worked out with such care that there is no doubt of the substantial truth of the results.

The terminal moraine of the great glacier has been carefully traced through several States. We now know that one vast sea of ice covered the eastern part of North America, down to about the thirty-ninth parallel of latitude. We have every reason to think that the great glacier, extending many miles out in the Atlantic, terminated in a great sea of ice, rising several hundred feet perpendicularly above the surface of the water. Long Island marks the southern extension of this glacier. From there its temporal moraine has been traced west, across New Jersey and Pennsylvania, diagonally across Ohio, crossing the river near Cincinnati, and thence west across Indiana and Illinois. West of the Mississippi it bears off to the north- west, and finally passes into British America.4

All of North America, to the north and northeast of this line, must have been covered by one vast sea of ice.5 Doubtless, as in Greenland to-day, there was no hill or patch of earth to be seen, simply one great field of ice. The ice was thick enough to cover from sight Mt. Washington, in New Hampshire, and must have been at least a mile thick over a large portion of this area,6 and even at its southern border it must in places have been from two hundred to two thousand feet thick.7 This, as we have seen, is a picture very similar to what must have been presented by Europe at this time.8

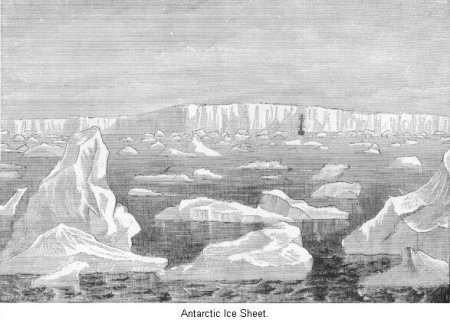

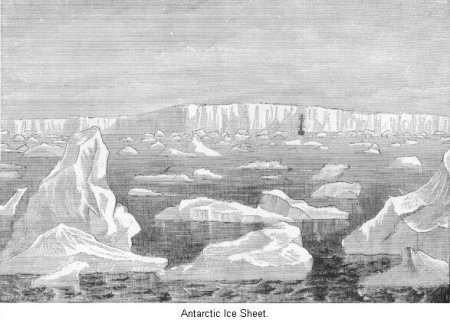

The Northern Atlantic Ocean must have presented a dreary aspect. Its shores were walls of ice, from which ever and anon great masses sailed away as icebergs. These are startling conclusions. Yet, in the Southern Hemisphere to-day is to be seen nearly the same state of things. It is well-known that all the lands around the South Pole are covered by a layer of ice of enormous thickness. Sir J. A. Ross, in attempting to reach high southern latitudes, while yet one thousand four hundred miles from the pole, found his further progress impeded by a perpendicular wall of ice one hundred and eighty feet thick. He sailed along that barrier four hundred and fifty miles, and then gave up the attempt. Only at one point in all that distance did the ice wall sink low enough to allow of its upper surface being seen from the mast-head. He describes the upper surface as an immense plain shining like frosted silver, and stretching away as far as eye could reach into the illimitable distance.9

The foregoing makes plain to us one phase of the Glacial Age. Though it may not be quite clear what this has to do with the antiquity of man, yet we will see, in the sequel, that it has considerable. As to the periods of mild climate that are thought by some to have broken up the reign of cold, we do not feel that we can say any thing in addition to what has been said in a former chapter.10

We might, however, say, that the sequences of mild and cold climate are not as well made out in America as they seem to be in Europe; or at least our geologists are more cautious as to accepting the evidence as sufficient. And yet such evidences are not wanting: as in Europe, at various places, are found layers of land surfaces with remains of animals and plants, but both above and below such surface soil are found beds of bowlder clay. These offer undeniable evidence that animals and plants occupied the land during temperate inter-glacial epochs, preceded and followed by an Arctic climate, and ice-sheets like those now covering the interior of Greenland, and the Antarctic Continent.11

We have thus, though somewhat at length, gone over the evidence as to the reality and severity of the Glacial Age. It was during the continuance of such climate that Paleolithic man arrived in Europe, though it was not perhaps until its close. We must not lose sight of the fact that our principal object at present is to determine, if we can, a date for either the beginning or ending of this extraordinary season of cold, and thereby achieve an important step in determining the antiquity of man.

A moment's consideration will show us that a period of cold sufficient to produce over a large portion of the Northern Hemisphere the results we have just set forth must have a cause that is strange and far-reaching. It can not be some local cause, affecting but one continent, since the effect produced is observed as well in Europe as in America.

Every year we pass through considerable changes in climate. The four seasons of the year seem to be but an annual repetition, on a very small scale of course, of the great changes in the climate of the earth that culminated in the Glacial Age; though we do not mean to say, that periods of glacial cold come and go with the regularity of our Winter. The changes in the seasons of the year are caused by the earth's position in its orbit, and its annual revolution around the sun. It may be that the cause of the Glacial Age itself is of a similar nature; in which case it is an astronomical problem, and we ought, by calculation, to determine, with considerable accuracy, dates for the beginning and ending of this epoch.

Nothing is clearer than that great fluctuations of climate have occurred in the past. Many theories have been put forth in explanation. It has been suggested that it was caused by loss of heat from the earth itself. That the earth was once a ball of incandescent matter, like the sun, and has since cooled down, is of course admitted. More than that, this process still continues; and the time must come when the earth, having yielded up its internal heat, will cease to be an inhabitable globe. But the climate of the surface of the earth is not dependent upon the heat of the interior. This now depends "according to the proportion of heat received either directly or indirectly from the sun; and so it must have been during all the ages of which any records have come down to us."12 Some have supposed that the sun, traveling as it does through space, carrying the earth and the other planets with him, might, in the course of ages, pass through portions of space either warmer or colder than that in which it now moves. When we come to a warm region of space, a genial climate would prevail over the earth; but, when we struck a cold belt, eternal Winter would mantle a large part of the globe with snow and ice. This, of course, is simply guess-work. No less than seven distinct causes have been urged; most of them either purely conjectural, like the last, or manifestly incompetent to produce the great results which we have seen must be accounted for. But, amongst these, two causes have been advanced—the one astronomical, the other geographical; and, to the one or the other, the majority of scholars have given their consent.

It will be no harm to see what can be said in favor of both theories. So, we will ask the reader's attention, as it is our earnest desire to make as plain as possible a question that has so much to do with our present inquiry. In the course of our investigations, we can not fail to catch glimpses of wonderful changes in far away times; and can not help seeing what labor is involved in the solution of all questions relating to the same.13

The earth revolves around the sun in an orbit called an ellipse. This is not a fixed form, but slowly varies from year to year. It is now gradually becoming circular. It will, however, not become an exact circle. Astronomers assure us that, after a long lapse of time, it will commence to elongate as an ellipse again. Thus, it will continually change from an ellipse to an approximate circle, and back again. In scientific language, the eccentricity of, the earth's orbit is said to increase and decrease.

In common language we would state that the shape of the path of the earth around the sun was sometimes much more elongated and elliptical than at others. The line drawn through the longest part of an ellipse is called the major axis. Now the sun does not occupy the center of this line, but is placed to one side of it; or, in other words, occupies one focus of the ellipse. It will thus be seen that the earth, at one time during its yearly journey, is considerably nearer to the sun than at others. The point where it approaches nearest the sun is called Perihelion, and the point where it reaches the greatest distance from the sun is called its Aphelion. It will be readily seen that the more elliptical its orbit becomes the greater will be the difference between the perihelion and aphelion distance of the sun. At present the earth is about three millions of miles nearer the sun in perihelion than in aphelion. But we must remember the orbit of the earth is now nearly circular. There have been times in the past when the difference was about thirteen millions of miles. We must not forget to add, that the change in the shape of the earth's orbit is not a regular increase and decrease between well-known extremes. It is caused by the attraction of the other planets. It has been calculated at intervals of ten thousand years for the last million years. In this way it has been found that "the intervals between connective turning points are very unequal in length, and the actual maximum and minimum values of the eccentricity are themselves variable. In this way it comes about that some periods of high eccentricity have lasted much longer than others, and that the orbit has been more elliptical at some epochs of high eccentricity than at others."14 We have just seen that the earth is nearer the sun at one time of the year than at another. At present the earth passes its perihelion point in the Winter of the Northern Hemisphere, and its aphelion point in the Summer. We will for the present suppose that it always reaches the points at the same season of the year. Let us see if the diminished distance from the sun in Winter has any thing to do with the climate.

If so, this effect will be greatly magnified during a period of high eccentricity, such as the earth has certainly passed through in the past. We will state first, that the more elliptical the orbit becomes, the longer Summer we have, and the shorter Winter. Astronomically, Spring begins the 20th of March, and Fall the 22d of September. By counting the days between the epochs it will be found that the Spring and Summer part of the year is seven days longer than the Fall and Winter part. But if the earth's orbit becomes as highly eccentrical as in the past, this difference would be thirty-six days.15

This would give us a long Spring and Summer, but a short Fall and Winter. This in itself would make a great difference. We must beer in mind, however, that at such a time as we are here considering, the earth would be ten millions of miles nearer the sun in Winter than at present. It would certainly then receive more heat in a given time during Winter than at present.16 Mr. Croll estimates that whereas the difference in heat received during a given time is now one-fifteenth,17 at the time we are considering it would be one-fifth. Hence we see that at such a time the Winter would not only be much shorter than now, but at the same time would be much milder.

These are not all the results that would follow an increase of eccentricity. The climate of Europe and North America is largely modified by those great ocean currents—the Gulf Stream and the Japan current. Owing to causes we will not here consider, these currents would be greatly increased at such a time. As a result of these combined causes, Mr. Croll estimates that during a period of high eccentricity the difference between Winter and Summer in the Northern Hemisphere would be practically obliterate. The Winter would not only be short, but very mild, and but little snow would form, while the sun of the long Summers, though not shining as intense as at present, would not have to melt off a great layer of snow and ice, but the ground became quickly heated, and so warmed the air. Hence, if Mr. Croll be correct, a period of high eccentricity would certainly produce a climate in the Northern Hemisphere such as characterized many of the mild interglacial epochs as long as the earth passed its perihelion point in Winter.

We have so far only considered the Northern Hemisphere. As every one knows, while we have Winter, the Southern Hemisphere has Summer. So at the very time we would enjoy the mild short Winters, the Southern Hemisphere would be doomed to experience Winters of greatly increased length and severity. As a consequence, immense fields of snow would be formed, which, by pressure, would be changed to ice, and creep away as a desolating glacier. It is quite true that the short Summer sun would shine with increased warmth, but owing to many causes it would not avail to free the land from snow and ice.

As Mr. Geikie points out, "An increased amount of evaporation would certainly take place, but the moisture-laden air would be chilled by coming into contact with the vast sheets of snow, and hence the vapor would condense into thick fogs and cloud the sky. In this way the sun's rays would be, to a large extent, cut off, and unable to reach the earth, and consequently the Winter's snow would not be all melted away." Hence it follows that at the very time the Northern Hemisphere would enjoy a mild interglacial climate, universal Spring, so to speak, the Southern Hemisphere would be encased in the ice and snow of an eternal Winter.

But the earth has not always reached its perihelion point during the Winter season of the Northern Hemisphere. Owing to causes that we need not here consider, the earth reaches its perihelion point about twenty minutes earlier each year, so if it now passes its perihelion in Winter of the Northern Hemisphere, in about ten thousand years from now it will reach it in Summer, and in twenty-one thousand, years it will again be at perihelion in Winter. But see what important consequences follow from this. If during a period of high eccentricity we are in the enjoyment of short mild Winters and long pleasant Summers, in ten thousand years this would certainly be changed. Our Summer season would become short and heated; our Winters long and intensely cold. Year by year it would be later in the season before the sun could free the land from snow, and at length in deep ravines and on hill-tops the snow would linger through the brief Summer, and the mild interglacial age will have passed away, and again the Northern Hemisphere will be visited by snow and ice of a truly. Glacial Age. If, therefore, a period of high eccentricity lasts through the many thousand years, we must expect more than one return of glacial cold interspersed by mild interglacial climates.

We have tried in these last few pages to give a clear statement of what is known as Croll's theory of the Glacial Age. There is no question but what the earth does thus vary in its position with regard to the sun, and beyond a doubt this must produce some effect on the climate, and we can truthfully state that the more the complicated question of the climate of the earth is studied, the more grounds do scholars find for affirming that indirectly this effect must have been very great. And yet we can not say that this theory is accepted as a satisfactory one even by the majority of scholars. Many of those who do not reject it think it not proven. Therefore, before interrogating the astronomer as to the data of the Glacial Age, according to the terms of this theory, let us see what other causes are, adduced; then we can more readily accept or reject the conclusions as to the antiquity of man which this theory would necessitate us to adopt.

The only other cause to which we can assign the glacial cold, that is considered with any favor by geologists, is geographical; that is to say, depending on the distribution of land and water. Glaciers depend on the amount of snow-fall. In any country where the amount of snow-fall is so great that it is not all evaporated or melted by the Summer's sun, and consequently increases from year to year, glaciers must soon appear, and these icy rivers would ere-long, flow away to lower levels. If we suppose, with Sir Charles Lyell, that the lands of the globe were all to be gathered around the equator, and the waters were gathered around the poles, it is manifest that there would be no such a thing as extremes of temperature, and it is, perhaps, doubtful whether ice would form, even in polar areas.18 At any rate, no glaciers could be formed, as there would be no land on which snow could gather in great quantities.

If, however, we reverse this picture, and conceive of the land gathered in a compact mass around the poles, shutting out the water, but consider the equatorial region of the earth to be occupied by the waters of the ocean, we would manifestly have a very different scene. From the ocean moisture-laden winds would flow over the polar lands. The snowfall would necessarily be great. In short, we can not doubt but what all the land of the earth would be covered with glaciers.19

Although these last conceptions are purely hypothetical, they will serve the good purpose of showing the great influence that the geographical distribution of land and water have on the climate of a country. Of one thing, however, geologists have become more and more impressed of late years. That is, that continents and oceans have always had the same relative position as now; that is to say, the continents have followed a definite plan in their development. The very first part of North America to appear above the waters of the primal sea clearly outlined the shape of the future continent. Mr. Dana assures us that our continent developed with almost the regularity of a flower. Prof. Hitchcock also points out that the surface area of the very first period outlined the shape of the continent. "The work of later geological periods seems to have been the filling up of the bays and sounds between the great islands, elevating the consolidated mass into a continental area."20 So it is not at all probable that the lands of the globe were ever grouped, as we have here supposed them.

This last statement is liable, however, to leave us under a wrong impression; for although, as a whole, continental areas have been permanent, yet in detail they have been subject to wonderful and repeated changes. "Every square mile of their surface has been again and again under water, sometimes a few hundred feet deep—sometimes, perhaps, several thousand. Lakes and inland seas have been formed and been filled up with sediment, and been subsequently raised into hills, or even mountains. Arms of the sea have existed, crossing the continent in various directions, and thus completely isolating the divided portions for varying intervals. Seas have become changed into deserts and deserts into seas."21

It has been shown beyond all question that North-western Europe owes its present mild climate to the influence of the Gulf Stream.22 Ocean currents, then, are a most important element in determining the climate of a country. If we would take the case of our hypothetical polar continent again, and, instead of presenting a continuous coast line, imagine it penetrated by long straits and fiords, possessing numerous bays, large inland seas, and in general allowing a free communication with the ocean, we are very sure the effect would be widely different.

Under these circumstances, says Mr. Geikie, the "much wider extent of sea being exposed to the blaze of the tropical sun, the temperature of the ocean in equatorial regions would rise above what it is at present. This warm water, sweeping in broad currents, would enter the polar fiords and seas, and everywhere, beating the air, would cause warm, moist winds to blow athwart the land to a much greater extent than they do at present; and these winds thus distributing warmth and moisture, might render even the high latitude of North Greenland habitable by civilized man." So we see that it is necessary to look for such geographical changes as will interfere with the movements of marine currents.

Now, it is easy to see that comparatively small geographical changes would not only greatly interfere with these currents, but might even cause them to entirely change their course. An elevation of the northern part of North America, no greater in amount than is supposed to have taken place at the commencement of the Glacial Age, would bring the wide area of the banks of Newfoundland far above the water, causing the American coast to stretch out in an immense curve to a point more than six hundred miles east of Halifax, and this would divert much of the Gulf Stream straight across to the coast of Spain.23

Such an elevation certainly took place, and if continued westward, Behring's Strait would also have been closed. It is to such northern elevations, shutting out the warm ocean currents, that a great many geologists look for a sufficient explanation of the glacial cold.

Prof. Dana says: "Increase in the extent and height of high latitude lands may well stand as one cause of the Glacial Age." Then he points out how the rising of the land of Northern Canada and adjacent territory, which almost certainly took place, "all a sequel to the majestic uplift of the Tertiary, would have made a glacial period for North America, whatever the position of the ecliptic, or whatever the eccentricity of the earth's orbit, though more readily, of course, if other circumstances favored it."24

It may occur to some that if high northern lands be all that is necessary for a period of cold, we ought to have had it in the Miocene Age, when there was a continuous land connection between the lands of high polar areas and both Europe and America, since we know that an abundant vegetation spread from there, as a center, to both these countries. But at that epoch circumstances were different. The great North Temperate lands were in a "comparatively fragmentary and insular condition."25 There were great inland seas in both Europe and Asia, through which powerful currents would have flowed from the Indian Ocean to Arctic regions.

Somewhat similar conditions prevailed in North America. The western part was in an insular condition. A great sea extended over this part of the country, joining the Arctic probably on the north, through which heated water would pour into the polar sea. And so, instead of a Glacial Age, we find evidence of a mild and genial climate, with an abundant vegetation.

We thus see that there are two theories as to the cause of the Glacial Age presented for our consideration. Both of them have received the sanction of scholars eminent for their scientific attainments. On inspection we see they are not antagonistic theories. They may both be true for that matter, and all would admit that whatever effect they would produce singly would be greatly enhanced if acting together. Indeed, there are very good reasons for supposing both must have acted in unison.

There seem to be very good reasons for not believing that the eccentricity of the earth's orbit, acting alone, produced the glacial cold. If that were the case, then whenever the eccentricity was great we should have a Glacial Age. Now, at some period of time during the long-extended Tertiary Age we are certain the eccentricity of the earth's orbit became very great, much more so, in fact, than that which is supposed to have produced the cold of the Quaternary Age. But we are equally certain there was no glacial epoch during this age.26 What other explanation can we give for its non-appearance except that geographical conditions were not favorable?

But, on the other hand, there are certain features connected with the phenomena of the Glacial Age that seem very difficult of explanation, if we suppose that geographical changes alone produced them. We must remember that evidences of the former presence of glaciers are found widely scattered over the earth. We shall, therefore, have to assume an elevation not only for America and Europe, but extend it over into Asia, and take in the Lebanon Mountains, for they also show distinct traces of glaciers. And this movement of elevation must also have affected the Southern Hemisphere, the evidence being equally plain that at the same comparatively late date glaciers crushed over Southern Africa and South America.27 This is seen to prove too much. Again, how can we explain the fact that some time during the Glacial Age we had a submergence, the land standing several hundred feet lower than now, but still remained covered with ice, and over the submerged part there sailed icebergs and ice-rafts, freighted with their usual débris? That such was the state of things in Europe we are assured by some very good authorities.28

Neither do geographical causes afford an adequate explanation of those changes of temperature that surely took place during the Glacial Age. These last considerations show us how difficult it is to believe that geographical causes could have produced the Glacial Age.

We are assured that all through the geological ages the continents had been increasing in size and compactness, and that just at the close of the Tertiary Age they received a considerable addition of land to the north. The astronomer also informs us that at a comparatively recent epoch the eccentricity of the earth's orbit became very great. The conditions being favorable, it is not strange that a Glacial Age supervened.

We have been to considerable length in thus explaining the position of the scientific world in regard to the cause of the Glacial Age. Our reason for so doing is that this age is, we think, so connected with the Paleolithic Age of man, that it seems advisable to have a clear understanding in regard to it. What we have to say is neither new nor original. It is simply an earnest endeavor to represent clearly the conclusions of some of our best scholars on this subject, and we have tried to give to each theory its due weight. Our conclusions may be wrong, but, if so, we have the consolation of erring in very good company.

We have now gone over the ground and are ready to see what dates can be given. Though the numbers we use seem to be very large indeed, they are so only in comparison with our brief span of life. They are insignificant as compared with the extent of time that has surely rolled by since life appeared on the globe. Let us, therefore, not be dismayed at the figures the astronomer sets before us.29

About two hundred and fifty thousand years ago the earth's path around the sun was much the same as that of the present. No great changes in climate were liable to take place at that time. During the next fifty thousand years the eccentricity steadily increased. Towards the end of that time all that was necessary to produce a glacial epoch in the Northern Hemisphere was favorable geographical causes, and that our earth should reach its point nearest the sun in Summer. This it must have done when about half that time had elapsed.

We can in imagination see what a slow deterioration of climate took place. Thousands of years would come and go before the change would be decisive. But a time must have at length arrived when the vegetation covering the ground was such as was suited only for high northern latitudes. The animals suited for warm and temperate regions must have wandered farther south; others from the north had arrived to take their place. We can see how well this agrees with the changes of climate at the close of the Pliocene Age. The snows of the commencing Glacial Age would soon begin to fall, finally the sun would not melt them off of the high lands, and mountain peaks, and so a Glacial Age would be ushered in.

We have referred to the fact that the earth reaches its perihelion point a little earlier each year, and, as a consequence, we would have periods of mild climate alternating the cold. This extended period of time, equal to twenty-one thousand of our ordinary years, has been named the Great Year of our globe. Mr. Wallace has pointed out some very good reasons for thinking Mr. Croll's theory must be modified on this point. He thinks that when once a Glacial Age was fairly fastened on a hemisphere, it would retain its grasp as long as the eccentricity remained high, but whenever the Summer of the Great Year came to that hemisphere, it would melt back the glacial ice for some distance, but this area would be recovered by the ice when the Winter of the Great Year supervened. These effects would be different when the eccentricity itself became low. Then we would expect the glacial conditions to vanish entirely when the Summer of a Great Year comes on.30

As we have made the theoretical part of this chapter already too long, we must hurry on. We can only say that this view is founded on the fact that when a country was covered with snow and ice, it had so to speak, a great amount of cold stored up in it, so much, in fact, that it would not be removed by the sun of a new geological Summer. This ought to be acceptable to such geologists as are willing to admit the advance and retreat of the great glacier, but yet doubt the fact of the interglacial mild climate.

But now to return to the question of time about two hundred and twenty thousand years ago. Then the Northern Hemisphere, according to this theory, was in the grasp of a Glacial Age. According to Mr. Wallace, as long as the eccentricity remained high, there could be no great amelioration of climate, except along the southern border of the ice sheet, which might, for causes named, vary some distance during the Great Year. Two hundred thousand years ago the eccentricity, then very high, reached a turning point. It then steadily, though gradually, diminished for fifty thousand years; at that time the eccentricity was so small, though considerably larger than at present, that it is doubtful if it was of any service in producing a change of climate.31 At that time, also, the Northern Hemisphere was passing through the Summer season of the Great Year. We ought, therefore, to have had a mild interglacial season. Except in high northern latitudes the ice should have disappeared. This change we would expect to find more marked in Europe than in America.

We need only recall how strong are the evidences on this point. Nearly all European writers admit at least one such mild interval, and though not wanting evidence of such a period in America, our geologists are much less confident of its occurrence.

But from that point the eccentricity again increased. So when the long flight of years again brought secular Winter to the Northern Hemisphere, the glaciers would speedily appear, and as eccentricity was again high, they would again hold the country in their grasp. Fifty thousand years later, or one hundred thousand years ago, it passed its turning point again; eighty thousand years ago, it became so small that it probably ceased to effect the climate. Since then it has not been very large. Twenty-five thousand years ago it was less than it is now, but it is again growing smaller. According to this theory, then, the Glacial Age commenced about two hundred and twenty thousand years ago. It continued, with one interruption of mild climate, for one hundred and forty thousand years, and finally passed away eighty thousand years ago.

What shall we say to these results? If true, what a wonderful antiquity is here unfolded for the human race, and what a wonderful lapse of time is included in what is known as the Paleolithic Age! How strikingly does it impress upon our minds the slow development of man! Is such an antiquity for man in itself absurd? We know no reason for such a conclusion. Our most eminent scholars nowhere set a limit to the time of man's first appearance. It is true, many of them do not think the evidence strong enough to affirm such an antiquity, but there are no bounds given beyond which we may not pass.

Without investigation some might reject the idea that man could have lived on the earth one hundred thousand years in a state of Savagism. If endowed with the attributes of humanity, it may seem to them that he would long before that time have achieved civilization. Such persons do not consider the lowliness of his first condition and the extreme slowness with which progress must have gone forward. On this point the geologists and the sociologists agree. Says Mr. Geikie: "The time which has elapsed from the close of the Paleolithic Age, even up to the present day, can not for a moment compare with the aeons during which the men of the old stone period occupied Europe." And on this subject Mr. Morgan says: "It is a conclusion of deep importance in ethnology that the experience of mankind in Savagery was longer in duration than all their subsequent experience, and that the period of Civilization covers but a fragment of the life of the race."32 The time itself, which seems to us so long, is but a brief space as compared with the ages nature has manifestly required to work out some of the results we see before us every day. We are sure, but few of our scholars think this too liberal an estimate. All endeavor to impress on our minds that the Glacial Age is an expression covering a very long period of time.

As to the time that has elapsed since the close of the Glacial Age there is some dispute, and it may be that we will be forced to the conclusion that the close of the Glacial Age was but a few thousand years ago. Mr. Wallace assures us, however, that the time mentioned agrees well "with physical evidence of the time that has elapsed since the cold has passed away."33

Difficulties are, however, urged by other writers. We can see at once that as quick as the glaciers are removed the denuding forces of nature, which are constantly at work, would begin to rearrange the débris left behind on the surface, and in the course of a few thousand years must effect great changes. Now, in some cases the amount of such change is so small that geologists are reluctant to believe a vast lapse of time has occurred since the glaciers withdrew. Mr. Geikie tells us of some moraines in Scotland that they are so fresh and beautiful "that it is difficult to believe they can date back to a period so vastly removed as the Ice Age is believed to be."34 In our own country this same sort of evidence is brought forward, and we are given some special calculations going to show that the disappearance of the glaciers was a comparatively recent thing.35

It will be seen that these conclusions are somewhat opposed to the results previously arrived at. In explanation Mr. Geikie thinks the cases spoken of in Scotland were not the moraines of the great glaciers, but of a local glacier of a far later date. He thinks that the climate, while not severe enough to produce the enormous glaciers of early times, was severe enough to produce local glaciers still in Scotland.36 It is possible that a similar explanation may be given for the evidence adduced in the United States. We can only state that, according to the difference in climate between the eastern and western sides of the Atlantic Ocean, when the climate was severe enough to produce local glaciers in Scotland, it would produce the same effect over a large part of eastern United States down to the latitude of New York City.37 And while it is true there would not be as much difference in climate on the two sides of the Atlantic in Glacial times as at present, since the Gulf Stream, on which such difference depends would then have less force, still it was not entirely lacking, and the difference must have been considerable.38

Prof. Hitchcock has made a suggestion that whereas we know a period of several months elapses after the sun crosses the equator before Summer fairly comes on, so it is but reasonable to suppose that a proportionate length of time would go by after the eccentricity of the earth's orbit became small, before the Glacial Age would really pass away. He accordingly suggests it may have been only about forty thousand years since the glaciers disappeared.39

At the close of the Glacial Age Paleolithic man vanished from Europe. This, therefore, brings us to the conclusion of our researches into what is probably the most mysterious chapter of man's existence on the earth.

It may not come amiss to briefly notice the main points thus far made in our investigation of the past. As to the epoch of man's first appearance, we found he could not be expected to appear until all the animals lower than he had made their appearance. This is so because the Creator of all has apparently chosen that method of procedure in the development of life on the globe. According to our present knowledge, man might have been living in the Miocene Age, and with a higher degree of probability in the Pliocene. But we can not say that the evidence adduced in favor of his existence at these early times is satisfactory to the majority of our best thinkers. All agree that he was living in Europe at the close of the Glacial Age, and we think the evidence sufficient to show that he preceded the glaciers, and that as a rude savage he lived in Europe throughout the long extended portion of time known as the Glacial Age.

We also found evidence of either two distinct races of men inhabiting Europe in the Paleolithic Age, or else tribes of the same race, widely different in time and in culture. The one people known as the men of the River Drift apparently invaded Europe from Asia, along with the species of temperate animals now living there. This people seem to have been widely scattered over the earth. The race has probably vanished away, though certain Australian tribes may be descendants of them. They were doubtless very low in the scale of humanity, having apparently never reached a higher state than that of Lower Savagism. The second race of men inhabiting Europe during the Paleolithic Age were the Cave-dwellers. They seem to have been allied to the Eskimos of the North. They were evidently further advanced than the Drift men, but were still savages.

The Paleolithic Age in Europe seems to have terminated with the Glacial Age. But we are not to suppose it came to an end all over the earth at that time. On the contrary, some tribes of men never passed beyond that stage. When the light of civilization fell upon them they were still in the culture of the old Stone Age. We are to notice that in such cases the tribes thus discovered were very low in the scale. The probable data for the Paleolithic Age have formed the subject of this chapter. While claiming in support of them the opinions of some eminent scholars, we freely admit that it is not a settled question, but open to very grave objections, especially the date of the close of the Glacial Age, which seems to have been comparatively recent, at least in America. We think, however, that these objections will yet be harmonized with the general results. Neither is this claimed to be an exhaustive presentation of the matter. It is an outline only—the better to enable us to understand the mystery connected with the data of Paleolithic man.

In these few chapters we have been dealing with people, manners, arid times, of which the world fifty years ago was ignorant. Many little discoveries, at first apparently disconnected, are suddenly brought into new relation, and behold, ages ago, when the great continents were but just completed, races of men, with the stamp of humanity upon them, are seen filling the earth. With them were many great animals long since passed away. The age of animals was at an end. That of man had just begun.

The child requires the schooling of adversity and trial to make a complete man of himself, and it is even so with races of men. Who can doubt that struggling up from dense ignorance, contending against adverse circumstances, compelled to wage war against fierce animals, sustaining life in the midst of the low temperature which had loaded the Northern Hemisphere with snow and ice, had much to do in developing those qualities which rendered civilization possible.

As to the antiquity of man disclosed in these chapters, the only question that need concern us is whether it is true or not. Evidence tending to prove its substantial accuracy should be as acceptable as that disproving it. No great principle is here at stake. The truth of Divine Revelation is in no wise concerned. There is nothing in its truth or falsity which should in any way affect man's belief in an overruling Providence, or in an immortality beyond the grave, or which should render any less desirable a life of purity and honor. On the contrary, we think one of the greatest causes of thanksgiving mortals have is the possession of intellectual powers, which enable us to here and there catch a glimpse of the greatness of God's universe, which the astronomer at times unfolds to us; or, to dimly comprehend the flight of time since "The Beginning," which the geologist finds necessary to account for the stupendous results wrought by slow-acting causes.

It seems to us eminently fitting that God should place man here, granting to him a capacity for improvement, but bestowing on him no gift or accomplishment, which by exertion and experience he could acquire; for labor is, and ever has been, the price of material good. So we see how necessary it is that a very extended time be given us to account for man's present advancement. Supposing an angel of light was to come to the aid of our feeble understanding, and unroll before us the pages of the past, a past of which, with all our endeavors, we as yet know but little. Can we doubt that, from such a review, we would arise with higher ideas of man's worth? Our sense of the depths from which he has ascended is equated only by our appreciation of the future opening before him. Individually we shall soon have passed away. Our nation may disappear. But we believe our race has yet but fairly started in its line of progress; time only is wanted. We can but think that that view which limits man to an existence extending over but a few thousand years of the past, is a belittling one. Rather let us think of him as existing from a past separated from us by these many thousand years; winning his present position by the exercise of God-given powers.

REFERENCES

WE have already remarked, geological periods give us no insight as to the actual passage of years. To say that man lived in the Glacial Age, and that we have some faint traces of his presence in still earlier periods, after all conveys to our minds only vague ideas of a far-away time. The more a geologist studies the structure of the earth, the more impressed is he with the magnitude of the time that must have passed since "The Beginning." At present, however, there are no means known of accurately measuring the time that has passed. It is just as well that it is so, since, were it known, the human mind would be utterly incapable of comprehending it. But as to the antiquity of man, it is but natural that we should seek more particularly to solve the problem and express our answer in some term of years.

Now, we have seen that the question of the antiquity of man is intimately connected with that of the Glacial Age. That is to say, the relics of man as far as we know them in Europe, are found under such circumstances that we feel confident they are not far removed from the period of cold. For it will be found that those conservative scholars who do not think that man preceded the Glacial Age, or inhabited Europe during the long course of years included in that period, do think he came into Europe as soon as it passed away. So, in any case, if we can determine the date of the Glacial Age, we shall have made a most important step in advance in solving the problem of the antiquity of man himself. So it seems to us best to go over the subject of the Glacial Age again, and see what conclusions some of our best thinkers have come to as to its cause, when it occurred, and other matters in relation to it.

It is best to state frankly at the outset that this topic is one of the great battle-grounds of science to-day, and that there are as yet but few points well settled in regard to it. One needs but attempt to read the literature on this subject to become quickly impressed with the necessity of making haste slowly in forming any conclusions. He must invoke the aid of the astronomer, geologist, physical-geographer, and physicist. Yet we must not suppose that questions relating to the Glacial Age are so abstruse that they are of interest only to the scholar. On the contrary, all ought to be interested in them. They open up one of the most wonderful chapters in the history of the world. They recall from the past a picture of ice-bound coasts and countries groaning under icy loads, where now are harbors enlivened by the commerce of the world, or ripening fields attesting the vivifying influence of a genial sun. Let us, therefore, follow after the leaders in thought. When we come to where they can not agree we can at least see what both sides have to say.

Somewhat at the risk of repetition, we will try and impress on our readers a sense of the reality and severity of the Glacial Age. There is danger in regarding this as simply a convenient theory that geologists have originated to explain some puzzling facts, that it is not very well founded, and is liable to give way any day to some more ingenious explanation. On the contrary, this whole matter has been worked out by very careful scholars. "There is, perhaps, no great conclusion in any science which rests upon a surer foundation than this, and if we are to be guided by our reason at all in deducting the unknown from the known, the past from the present, we can not refuse our assent to the reality of the Glacial Age of the Northern Hemisphere in all its more important features.2 At the present day glaciers do exist in several places on the earth. They are found in the Alps and the mountains of Norway, and the Caucasus, in Europe. The Himalaya mountains support immense glaciers in Asia; and in America a few still linger in the more inaccessible heights of the Sierra Nevada. It is from a study of these glaciers, mainly however, those of the Alps, that geologists have been enabled to explain the true meaning of certain formations they find in both Europe and America, that go by the name of drift.

When in an Alpine valley we come upon a glacier, filling it from side to side, there will be noticed upon both sides a long train of rock, drift, and other débris that have fallen down upon its surface from the mountain sides. If two of these ice-rivers unite to form one glacier, two of these trains will then be borne along in the middle of the resulting glacier. As this glacier continues down the valley, it at length reaches a point where a further advance is rendered impossible by the increased temperature melting the ice as fast as it advances. At this point the train of rocks and dirt are dumped, and of course form great mounds, called moraines. The glacier at times shrinks back on its rocky bed and allows explorers to examine it.

In such cases they find the rocks smoothed and polished, but here and there marked with long grooves and striæ. These points are learned from an examination of existing glaciers. Further down the valley, where now the glaciers never extend, are seen very distinctly the same signs. There are the same moraines, striated rocks, and bowlders that have evidently traveled from their home up the valley. The only explanation possible in this case is that once the glaciers extended to that point in the valley.

It required a person who was perfectly familiar with the behavior of Alpine glaciers, and knew exactly what marks they left behind in their passage, to point out the proofs of their former presence in Northern Europe and America, where it seems almost impossible to believe they existed. Such a man was Louis Agassiz, the eminent naturalist. Born and educated in Switzerland, he spent nine years in researches among the glaciers of the mountains of his native country. He proved the former wide extension of the glaciers of Switzerland. With these results before them, geologists were not long in showing that there had once been glacial ice over a large part of Europe and North America.

The proofs in this case are almost exactly the same as those used to show that the ancient glaciers of Switzerland were once larger than now. But as the great glaciers of the glacial age were many times larger than any thing we know of at the present day, there were of course different results produced.

For instance, the water circulating under Alpine glaciers is enabled to wash out and carry away the mass of pulverized rock and dirt ground along underneath the ice. But when the glaciers covered such an enormous extent of country as they did in the Glacial Age, the water could not sweep away this detritus, and so great beds of gravel, sand, and clay would be formed over a large extent of country. But to go over the entire ground would require volumes; it is sufficient to give the results.

The interior of Greenland to-day is covered by one vast sea of ice. Explorers have traversed its surface for many miles; not a plant, or stone, or patch of earth is to be seen. In the Winter it is a snow-swept waste. In the Summer streams of ice-cold water flow over its surface, penetrating here and there by crevasses to unknown depths. This great glacier is some twelve hundred miles long, by four hundred in width.3 Vast as it is, it is utterly insignificant as compared with the great continental glacier that geologists assure us once held in its grasp the larger portion of North America.

The conclusions of some of our best scholars on this subject are so opposed to all that we would think possible, according to the present climate and surroundings, that they seem at first incredible, and yet they have been worked out with such care that there is no doubt of the substantial truth of the results.

The terminal moraine of the great glacier has been carefully traced through several States. We now know that one vast sea of ice covered the eastern part of North America, down to about the thirty-ninth parallel of latitude. We have every reason to think that the great glacier, extending many miles out in the Atlantic, terminated in a great sea of ice, rising several hundred feet perpendicularly above the surface of the water. Long Island marks the southern extension of this glacier. From there its temporal moraine has been traced west, across New Jersey and Pennsylvania, diagonally across Ohio, crossing the river near Cincinnati, and thence west across Indiana and Illinois. West of the Mississippi it bears off to the north- west, and finally passes into British America.4

All of North America, to the north and northeast of this line, must have been covered by one vast sea of ice.5 Doubtless, as in Greenland to-day, there was no hill or patch of earth to be seen, simply one great field of ice. The ice was thick enough to cover from sight Mt. Washington, in New Hampshire, and must have been at least a mile thick over a large portion of this area,6 and even at its southern border it must in places have been from two hundred to two thousand feet thick.7 This, as we have seen, is a picture very similar to what must have been presented by Europe at this time.8

The Northern Atlantic Ocean must have presented a dreary aspect. Its shores were walls of ice, from which ever and anon great masses sailed away as icebergs. These are startling conclusions. Yet, in the Southern Hemisphere to-day is to be seen nearly the same state of things. It is well-known that all the lands around the South Pole are covered by a layer of ice of enormous thickness. Sir J. A. Ross, in attempting to reach high southern latitudes, while yet one thousand four hundred miles from the pole, found his further progress impeded by a perpendicular wall of ice one hundred and eighty feet thick. He sailed along that barrier four hundred and fifty miles, and then gave up the attempt. Only at one point in all that distance did the ice wall sink low enough to allow of its upper surface being seen from the mast-head. He describes the upper surface as an immense plain shining like frosted silver, and stretching away as far as eye could reach into the illimitable distance.9

The foregoing makes plain to us one phase of the Glacial Age. Though it may not be quite clear what this has to do with the antiquity of man, yet we will see, in the sequel, that it has considerable. As to the periods of mild climate that are thought by some to have broken up the reign of cold, we do not feel that we can say any thing in addition to what has been said in a former chapter.10

We might, however, say, that the sequences of mild and cold climate are not as well made out in America as they seem to be in Europe; or at least our geologists are more cautious as to accepting the evidence as sufficient. And yet such evidences are not wanting: as in Europe, at various places, are found layers of land surfaces with remains of animals and plants, but both above and below such surface soil are found beds of bowlder clay. These offer undeniable evidence that animals and plants occupied the land during temperate inter-glacial epochs, preceded and followed by an Arctic climate, and ice-sheets like those now covering the interior of Greenland, and the Antarctic Continent.11

We have thus, though somewhat at length, gone over the evidence as to the reality and severity of the Glacial Age. It was during the continuance of such climate that Paleolithic man arrived in Europe, though it was not perhaps until its close. We must not lose sight of the fact that our principal object at present is to determine, if we can, a date for either the beginning or ending of this extraordinary season of cold, and thereby achieve an important step in determining the antiquity of man.

A moment's consideration will show us that a period of cold sufficient to produce over a large portion of the Northern Hemisphere the results we have just set forth must have a cause that is strange and far-reaching. It can not be some local cause, affecting but one continent, since the effect produced is observed as well in Europe as in America.

Every year we pass through considerable changes in climate. The four seasons of the year seem to be but an annual repetition, on a very small scale of course, of the great changes in the climate of the earth that culminated in the Glacial Age; though we do not mean to say, that periods of glacial cold come and go with the regularity of our Winter. The changes in the seasons of the year are caused by the earth's position in its orbit, and its annual revolution around the sun. It may be that the cause of the Glacial Age itself is of a similar nature; in which case it is an astronomical problem, and we ought, by calculation, to determine, with considerable accuracy, dates for the beginning and ending of this epoch.

Nothing is clearer than that great fluctuations of climate have occurred in the past. Many theories have been put forth in explanation. It has been suggested that it was caused by loss of heat from the earth itself. That the earth was once a ball of incandescent matter, like the sun, and has since cooled down, is of course admitted. More than that, this process still continues; and the time must come when the earth, having yielded up its internal heat, will cease to be an inhabitable globe. But the climate of the surface of the earth is not dependent upon the heat of the interior. This now depends "according to the proportion of heat received either directly or indirectly from the sun; and so it must have been during all the ages of which any records have come down to us."12 Some have supposed that the sun, traveling as it does through space, carrying the earth and the other planets with him, might, in the course of ages, pass through portions of space either warmer or colder than that in which it now moves. When we come to a warm region of space, a genial climate would prevail over the earth; but, when we struck a cold belt, eternal Winter would mantle a large part of the globe with snow and ice. This, of course, is simply guess-work. No less than seven distinct causes have been urged; most of them either purely conjectural, like the last, or manifestly incompetent to produce the great results which we have seen must be accounted for. But, amongst these, two causes have been advanced—the one astronomical, the other geographical; and, to the one or the other, the majority of scholars have given their consent.

It will be no harm to see what can be said in favor of both theories. So, we will ask the reader's attention, as it is our earnest desire to make as plain as possible a question that has so much to do with our present inquiry. In the course of our investigations, we can not fail to catch glimpses of wonderful changes in far away times; and can not help seeing what labor is involved in the solution of all questions relating to the same.13

The earth revolves around the sun in an orbit called an ellipse. This is not a fixed form, but slowly varies from year to year. It is now gradually becoming circular. It will, however, not become an exact circle. Astronomers assure us that, after a long lapse of time, it will commence to elongate as an ellipse again. Thus, it will continually change from an ellipse to an approximate circle, and back again. In scientific language, the eccentricity of, the earth's orbit is said to increase and decrease.

In common language we would state that the shape of the path of the earth around the sun was sometimes much more elongated and elliptical than at others. The line drawn through the longest part of an ellipse is called the major axis. Now the sun does not occupy the center of this line, but is placed to one side of it; or, in other words, occupies one focus of the ellipse. It will thus be seen that the earth, at one time during its yearly journey, is considerably nearer to the sun than at others. The point where it approaches nearest the sun is called Perihelion, and the point where it reaches the greatest distance from the sun is called its Aphelion. It will be readily seen that the more elliptical its orbit becomes the greater will be the difference between the perihelion and aphelion distance of the sun. At present the earth is about three millions of miles nearer the sun in perihelion than in aphelion. But we must remember the orbit of the earth is now nearly circular. There have been times in the past when the difference was about thirteen millions of miles. We must not forget to add, that the change in the shape of the earth's orbit is not a regular increase and decrease between well-known extremes. It is caused by the attraction of the other planets. It has been calculated at intervals of ten thousand years for the last million years. In this way it has been found that "the intervals between connective turning points are very unequal in length, and the actual maximum and minimum values of the eccentricity are themselves variable. In this way it comes about that some periods of high eccentricity have lasted much longer than others, and that the orbit has been more elliptical at some epochs of high eccentricity than at others."14 We have just seen that the earth is nearer the sun at one time of the year than at another. At present the earth passes its perihelion point in the Winter of the Northern Hemisphere, and its aphelion point in the Summer. We will for the present suppose that it always reaches the points at the same season of the year. Let us see if the diminished distance from the sun in Winter has any thing to do with the climate.

If so, this effect will be greatly magnified during a period of high eccentricity, such as the earth has certainly passed through in the past. We will state first, that the more elliptical the orbit becomes, the longer Summer we have, and the shorter Winter. Astronomically, Spring begins the 20th of March, and Fall the 22d of September. By counting the days between the epochs it will be found that the Spring and Summer part of the year is seven days longer than the Fall and Winter part. But if the earth's orbit becomes as highly eccentrical as in the past, this difference would be thirty-six days.15

This would give us a long Spring and Summer, but a short Fall and Winter. This in itself would make a great difference. We must beer in mind, however, that at such a time as we are here considering, the earth would be ten millions of miles nearer the sun in Winter than at present. It would certainly then receive more heat in a given time during Winter than at present.16 Mr. Croll estimates that whereas the difference in heat received during a given time is now one-fifteenth,17 at the time we are considering it would be one-fifth. Hence we see that at such a time the Winter would not only be much shorter than now, but at the same time would be much milder.

These are not all the results that would follow an increase of eccentricity. The climate of Europe and North America is largely modified by those great ocean currents—the Gulf Stream and the Japan current. Owing to causes we will not here consider, these currents would be greatly increased at such a time. As a result of these combined causes, Mr. Croll estimates that during a period of high eccentricity the difference between Winter and Summer in the Northern Hemisphere would be practically obliterate. The Winter would not only be short, but very mild, and but little snow would form, while the sun of the long Summers, though not shining as intense as at present, would not have to melt off a great layer of snow and ice, but the ground became quickly heated, and so warmed the air. Hence, if Mr. Croll be correct, a period of high eccentricity would certainly produce a climate in the Northern Hemisphere such as characterized many of the mild interglacial epochs as long as the earth passed its perihelion point in Winter.

We have so far only considered the Northern Hemisphere. As every one knows, while we have Winter, the Southern Hemisphere has Summer. So at the very time we would enjoy the mild short Winters, the Southern Hemisphere would be doomed to experience Winters of greatly increased length and severity. As a consequence, immense fields of snow would be formed, which, by pressure, would be changed to ice, and creep away as a desolating glacier. It is quite true that the short Summer sun would shine with increased warmth, but owing to many causes it would not avail to free the land from snow and ice.

As Mr. Geikie points out, "An increased amount of evaporation would certainly take place, but the moisture-laden air would be chilled by coming into contact with the vast sheets of snow, and hence the vapor would condense into thick fogs and cloud the sky. In this way the sun's rays would be, to a large extent, cut off, and unable to reach the earth, and consequently the Winter's snow would not be all melted away." Hence it follows that at the very time the Northern Hemisphere would enjoy a mild interglacial climate, universal Spring, so to speak, the Southern Hemisphere would be encased in the ice and snow of an eternal Winter.

But the earth has not always reached its perihelion point during the Winter season of the Northern Hemisphere. Owing to causes that we need not here consider, the earth reaches its perihelion point about twenty minutes earlier each year, so if it now passes its perihelion in Winter of the Northern Hemisphere, in about ten thousand years from now it will reach it in Summer, and in twenty-one thousand, years it will again be at perihelion in Winter. But see what important consequences follow from this. If during a period of high eccentricity we are in the enjoyment of short mild Winters and long pleasant Summers, in ten thousand years this would certainly be changed. Our Summer season would become short and heated; our Winters long and intensely cold. Year by year it would be later in the season before the sun could free the land from snow, and at length in deep ravines and on hill-tops the snow would linger through the brief Summer, and the mild interglacial age will have passed away, and again the Northern Hemisphere will be visited by snow and ice of a truly. Glacial Age. If, therefore, a period of high eccentricity lasts through the many thousand years, we must expect more than one return of glacial cold interspersed by mild interglacial climates.

We have tried in these last few pages to give a clear statement of what is known as Croll's theory of the Glacial Age. There is no question but what the earth does thus vary in its position with regard to the sun, and beyond a doubt this must produce some effect on the climate, and we can truthfully state that the more the complicated question of the climate of the earth is studied, the more grounds do scholars find for affirming that indirectly this effect must have been very great. And yet we can not say that this theory is accepted as a satisfactory one even by the majority of scholars. Many of those who do not reject it think it not proven. Therefore, before interrogating the astronomer as to the data of the Glacial Age, according to the terms of this theory, let us see what other causes are, adduced; then we can more readily accept or reject the conclusions as to the antiquity of man which this theory would necessitate us to adopt.

The only other cause to which we can assign the glacial cold, that is considered with any favor by geologists, is geographical; that is to say, depending on the distribution of land and water. Glaciers depend on the amount of snow-fall. In any country where the amount of snow-fall is so great that it is not all evaporated or melted by the Summer's sun, and consequently increases from year to year, glaciers must soon appear, and these icy rivers would ere-long, flow away to lower levels. If we suppose, with Sir Charles Lyell, that the lands of the globe were all to be gathered around the equator, and the waters were gathered around the poles, it is manifest that there would be no such a thing as extremes of temperature, and it is, perhaps, doubtful whether ice would form, even in polar areas.18 At any rate, no glaciers could be formed, as there would be no land on which snow could gather in great quantities.

If, however, we reverse this picture, and conceive of the land gathered in a compact mass around the poles, shutting out the water, but consider the equatorial region of the earth to be occupied by the waters of the ocean, we would manifestly have a very different scene. From the ocean moisture-laden winds would flow over the polar lands. The snowfall would necessarily be great. In short, we can not doubt but what all the land of the earth would be covered with glaciers.19

Although these last conceptions are purely hypothetical, they will serve the good purpose of showing the great influence that the geographical distribution of land and water have on the climate of a country. Of one thing, however, geologists have become more and more impressed of late years. That is, that continents and oceans have always had the same relative position as now; that is to say, the continents have followed a definite plan in their development. The very first part of North America to appear above the waters of the primal sea clearly outlined the shape of the future continent. Mr. Dana assures us that our continent developed with almost the regularity of a flower. Prof. Hitchcock also points out that the surface area of the very first period outlined the shape of the continent. "The work of later geological periods seems to have been the filling up of the bays and sounds between the great islands, elevating the consolidated mass into a continental area."20 So it is not at all probable that the lands of the globe were ever grouped, as we have here supposed them.

This last statement is liable, however, to leave us under a wrong impression; for although, as a whole, continental areas have been permanent, yet in detail they have been subject to wonderful and repeated changes. "Every square mile of their surface has been again and again under water, sometimes a few hundred feet deep—sometimes, perhaps, several thousand. Lakes and inland seas have been formed and been filled up with sediment, and been subsequently raised into hills, or even mountains. Arms of the sea have existed, crossing the continent in various directions, and thus completely isolating the divided portions for varying intervals. Seas have become changed into deserts and deserts into seas."21

It has been shown beyond all question that North-western Europe owes its present mild climate to the influence of the Gulf Stream.22 Ocean currents, then, are a most important element in determining the climate of a country. If we would take the case of our hypothetical polar continent again, and, instead of presenting a continuous coast line, imagine it penetrated by long straits and fiords, possessing numerous bays, large inland seas, and in general allowing a free communication with the ocean, we are very sure the effect would be widely different.

Under these circumstances, says Mr. Geikie, the "much wider extent of sea being exposed to the blaze of the tropical sun, the temperature of the ocean in equatorial regions would rise above what it is at present. This warm water, sweeping in broad currents, would enter the polar fiords and seas, and everywhere, beating the air, would cause warm, moist winds to blow athwart the land to a much greater extent than they do at present; and these winds thus distributing warmth and moisture, might render even the high latitude of North Greenland habitable by civilized man." So we see that it is necessary to look for such geographical changes as will interfere with the movements of marine currents.

Now, it is easy to see that comparatively small geographical changes would not only greatly interfere with these currents, but might even cause them to entirely change their course. An elevation of the northern part of North America, no greater in amount than is supposed to have taken place at the commencement of the Glacial Age, would bring the wide area of the banks of Newfoundland far above the water, causing the American coast to stretch out in an immense curve to a point more than six hundred miles east of Halifax, and this would divert much of the Gulf Stream straight across to the coast of Spain.23

Such an elevation certainly took place, and if continued westward, Behring's Strait would also have been closed. It is to such northern elevations, shutting out the warm ocean currents, that a great many geologists look for a sufficient explanation of the glacial cold.