Industrial archaeology originated in Britain in the 1950s, after the postwar preoccupation with renewal had led to the destruction of much of the landscape

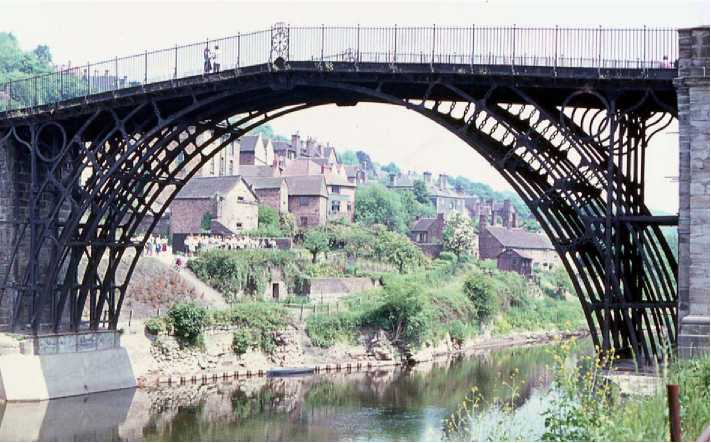

Figure 1 The Iron Bridge across the Severn Gorge in Shropshire, the world’s first iron bridge, cast in Abraham Darby’s Coalbrookdale foundry in 1777 and erected in 1779. Now in the care of English Heritage, the bridge was originally saved by the Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust and is the centerpiece of an industrial landscape accorded World Heritage status.

Associated with early industrialization. It is generally agreed that the term was first used in print by Michael Rix of the University of Birmingham Extra-mural Department in an article in The Amateur Historian, one of a sequence of articles dealing with various periods of archaeology. The banner was taken up in the UK by Kenneth Hudson in his Industrial Archaeology: an Introduction (John Baker, 1963), J. M. Pannell’s The Techniques of Industrial Archaeology (David and Charles, 1966), and Angus Buchanan in the Pelican Industrial Archaeology in Britain (1972).

Industrial Archaeology and Historical Archaeology

In the 1950s, there was no systematic investigation of the physical remains of the recent industrial past in the UK, since the peculiarly British ‘postmedieval archaeology’ generally concerned itself with the period from c. 1450 to c. 1750. The term ‘historical archaeology’ was not generally used in the UK until comparatively recently, even when it became current in the USA and Australia from the 1970s. This is partly because the written history of Europe goes back into classical times and ‘historical archaeology’ could be used to refer to any period where texts and physical evidence can be used in conjunction, for example, as in the Greek and Roman periods. Industrial archaeology was therefore an appropriate term for the study of the classic period of industrialization from c. 1750 onwards. Some early practitioners of industrial archaeology, however, argued that the discipline was a thematic rather than a chronological one and could range from the prehistoric to the modern period, notably Arthur Raistrick in his Industrial Archaeology: an Historical Survey (Eyre Methuen, 1972). It is now generally accepted that industrial archaeology is the systematic study of standing, as well as subsurface, structures of the classic period of industrialization from the eighteenth to the twentieth centuries. What characterizes this period is capital investment on a large scale in both buildings and machinery and the consequent organization of the labor force to maximize production. It is with this development that industrial archaeology is largely concerned, although it must be recognized firstly that ‘industrialization’, in this sense, began earlier in some industries than others and that therefore an interpretation of a particular site or industry may need to go back to the seventeenth century or earlier. Secondly, it is clear that the domestic or home-based method of production continued to coexist with factory production, albeit with many changes in the lifestyle of the workforce. The purpose of industrial archaeology, then, is to make use of a multidisciplinary approach, involving site and building survey, photography, stratigraphy, artifacts, landscapes, documentary research, and oral history to study, interpret, and, in some cases, preserve the physical evidence of the vast social and economic changes which have overtaken society in the past 250 years or so. It is generally concerned with the evidence for people at work and so defines a type of human activity rather than a type of site, since ‘work’, even after the so-called Industrial Revolution, could be based in domestic as well as nondomestic locations.

In areas of the world with a shorter written history, historical archaeology was taken to embrace the study of industrial sites and artifacts. It was pointed out by Ian Jack and Judy Birmingham in Australian Pioneer Technology: Sites and Relics (1979) that the use of the term ‘industrial archaeology’ in Australia was inappropriate since the time span of British industrial archaeology embraced the whole of Australian history since European settlement. In the USA, many historical archaeologists also did not see the need for a different term for the study of industrial sites, since again the majority of their work was concerned with the colonial era and its implications. This point was put forward vehemently in a paper by Vincent Foley in an early (1968) issue of Historical Archaeology (see Historical Archaeology: As a Discipline). He argued that ‘‘the archaeologist must dig for his data. The ‘industrial archaeologist’ is performing archaeology when he excavates a site. He is not an archaeologist, however, if this excavation is only occasional or accidental to his normal method of procuring data.’’ Foley was strongly opposed by a fellow American, Robert Vogel (who went on to play a major role in American industrial archaeology), who argued in the subsequent issue of Historical Archaeology that it was equally important to record, understand, and interpret aboveground structures, taking as an example the ruinous structures of the Tredegar ironworks in Richmond, Virginia, a bastion of Confederate ordnance production. Donald Hardesty, in his classic The Archaeology of Mining and Miners: A View from the Silver State (SHA, 1988), pointed out that so often the standing buildings, machinery, and landscape features characteristic of many British industrial sites did not survive on US mining sites but ‘‘they are rich in trash dumps, residential house foundations, privies and other remains of the miners themselves’’ and that therefore excavation was essential. In the UK, though, aboveground remains undoubtedly formed the basis of most British industrial archaeology in the first 30 years of its existence as a discipline and the material culture of the workforce, which might have been obtained through systematic excavation, was neglected. The secondary role of excavation in industrial archaeology undoubtedly hindered its acceptance as a legitimate form of archaeology for several decades but - at least in Europe - this is now less of a problem since nondestructive activities such as landscape and earthwork survey and building analysis have become fully accepted aspects of archaeological work.

More serious, though, was the fact that industrial archaeology concentrated on the technological analysis of specific industrial sites and areas and failed to consider the behavioral aspects of material culture or the processes of culture change. This justifiable criticism has only begun to be remedied in the 1990s and 2000s, when the advent of ‘interpretive’ or ‘post-processual’ approaches led to increasing concern with questions of power and inequality, labor relations, and class formation which are central research themes for industrial archaeology, as in Paul Shackel’s 1996 Culture Change and the New Technology: An Archaeology of the Early American Industrial Era. This development clearly brought industrial archaeology into a much closer relationship with existing subdiscipline of historical archaeology, as already practiced in North America, and Australasia.

Industrial Archaeology and Industrial Heritage

The initial impetus for industrial archaeology in the UK was, then, the attempt to study, catalog, and preserve selected relics of the period when Britain was the world leader in the process of industrialization. It was a spontaneous growth, resulting in volunteer activity on a considerable scale in both preservation and recording. The Council for British Archaeology, which represents both amateurs and professionals, tried to give some shape to the enthusiasm for industrial archaeology by the introduction of standardized record cards, completed by volunteers. This grew into the National Record of Industrial Monuments based first at the University of Bath under Angus Buchanan and later subsumed into the National Monuments Record (NMR) of the Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England (RCHME). Gazetteers of important industrial sites were built up on a county basis, many of which have found their way into local Sites and Monuments Records (now Historic Environment Records) and achieved a measure of recognition, if not always protection. English Heritage in the 1990s sought to take this activity to a national level by means of the Industrial Monuments Protection Programme, initially designed to update the lists of Ancient Monuments but resulting in some fundamental research on specific industries, especially in the extractive industries where landscape change threatened many sites. Unfortunately, the funding for this project was brought to an end prematurely in 2005 and the large amount of information gathered not adequately disseminated. Similar national recording programs of industrial sites have been carried out in other parts of the UK, especially in Northern Ireland where the government funded an official survey following a pilot study of County Down which had been carried out by E. R. R. Green in the late 1950s (Green was also to edit the first major series of regional industrial archaeology guides in the UK published by David and Charles). W. D. McCutcheon carried out this survey in the 1960s but his important The Industrial Archaeology ofNorthern Ireland was not published until 1980 (Figure 2). Similar

Figure 2 Wellbrook Beetling mill in Northern Ireland, a small water-powered mill for beetling or refining woven linen cloth, now in the possession of The National Trust.

Work was carried out on the threatened coal industry by the statutory organizations in England, Scotland, and Wales while Stephen Hughes’ magisterial study for the Welsh Royal Commission of the threatened landscape of ‘Copperopolis’, the lower Swansea Valley in South Wales, set new standards for the recording of industrial buildings in their cultural context. Colin Rynne of the University of Cork in Ireland, who has carried out some important recording work and published in 2006, Industrial Ireland 1750-1930: an Archaeology, has pointed out that Ireland was regarded as a colony and that its industrial heritage has also to be thought of as ‘British’, an argument that could be extended into the Caribbean and parts of the eastern USA as well as Australia.

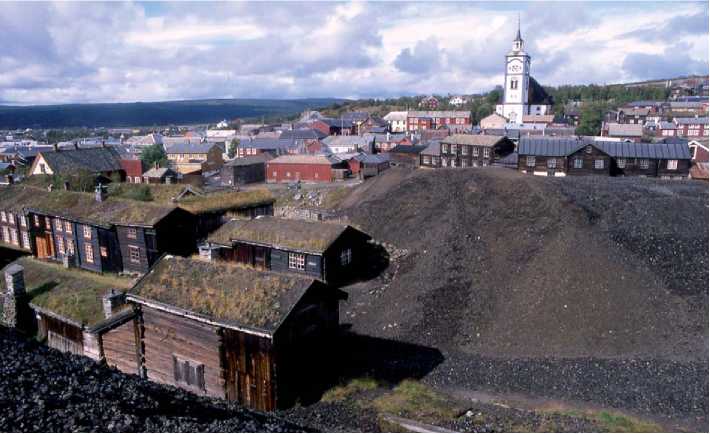

Inventory work on industrial sites followed in Europe, generally with more professional and less amateur involvement than in the UK. Although French historians had for a long time been interested in industrial history, little notice was taken of industrial sites until the 1970s and it was not until 1983 that the Inventaire Generale began to include industrial sites with the foundation of an industrial heritage group within it, the Cellule du Patrimoine Industriel. A longterm project to create a national database of French industrial sites was initiated in 1986, and a similar database project was begun in the Netherlands where responsibility for the industrial heritage passed to the Projectbureau Industrieel Erfgoed (PIE), created in 1992. In Belgium, various categories of industrial building have been surveyed, particularly watermills and windmills, and a national survey published by Patrick Viaene in 1986. The Scandinavian countries have an important industrial heritage, particularly in mining of copper and iron, which is increasingly being recognized as significant by their governments and both R0r0s in Norway and Falun in Sweden have been designated as World Heritage sites (Figure 3). In Norway, buildings and sites of industrial interest have been recorded both by the Council for Culture and the Norwegian Technical Museum, while in Sweden, motivated by Professor Marie Nisser, the Central Office of National Antiquities is monitoring various recording initiatives.

Further afield, industrial archaeology in the heritage sense has made rapid progress in Australia since the 1960s with the Australian National Trust publishing lists of industrial sites and conserving many of them at state level, notably the important mining landscapes of gold, copper, and silver at Moonta and Ballarat. In the United States, the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) was created in the 1930s but responsibility for recording industrial buildings and machinery is now shared by the Historical American Engineering Record (HAER), established in 1969 under the aegis of the National Park Service, which itself dates back to 1916. The records are maintained by the Library of Congress in what is termed ‘preservation by documentation’, a concept similar to that of the British National Monuments Records.

Preservation itself has undoubtedly played a more major role in industrial archaeology than in other forms of archaeology since its inception and this has, of course, meant that sites are often not excavated below what is felt to be the best level for public appreciation. For example, a steel cementation furnace in Sheffield was excavated to the level at which it had been truncated rather than destroy it to find any

Figure 3 Copper mining and smelting have dominated the Norwegian town of Roros since its foundation in the late-seventeenth century. Below the slaG heaps are the ramshackle wooden workers’ houses with their grassed roofs, while the company town is dominated by the late-eighteenth century Baroque church. Mining continued in Roros well into the twentieth century, but the importance of the town’s historic remains were carefully conserved and accorded World Heritage status in 1982.

Figure 4 One of a row of eight mid-nineteenth century cementation furnaces from the Brightside Works in Sheffield, excavated by ARCUS, the Archaeological Unit of the University of Sheffield (by permission of ARCUS, Sheffield).

Possible earlier remains (Figure 4). In Sweden, the medieval iron furnace at Lapphyttan was fully excavated archaeologically to understand more about the origins of blast furnace technology whereas the important standing structures of the iron making complex at Engelsberg, now a World Heritage Site, have been retained as industrial monuments in order to further public understanding of Sweden’s internationally important iron industry. In Poland, recording programs have been carried out on the numerous

Surviving headgears associated with the coal industry in the region around Katowice with a view to preserving the most important of these. Germany, the Netherlands, and the UK have cooperated in an important new initiative, the European Route of the Industrial Heritage Http://en. erih. net which links sites in all three countries, although the selection of sites is somewhat esoteric. In the USA, the National Parks Service has undertaken the consolidation and in some cases, the complete reconstruction of important industrial monuments, such as the early iron making furnaces at Saugus north of Boston and Hopewell in Pennsylvania and the site of Washington’s National Armory and Arsenal at Harper’s Ferry in West Virginia. The involvement of historical archaeologists has led to a greater concentration on the workforce involved at such sites, something that was neglected until recently in British studies, although the work of ARCUS, the Sheffield-based archaeological contract unit, has begun to correct the over-concentration in the UK on technological detail as opposed to the human face of industrial archaeology, (as can be seen in The Historical Archaeology of the Sheffield Cutlery and Tableware Industry 1750-1900, edited in 2002 by James Symonds.).

However, the way forward in the large-scale conservation of industrial sites and structures can only be through the process of ‘adaptive reuse’. Many are unsuitable for this technique, although exciting projects for the reuse of nineteenth century steel-cased blast furnaces are already in place in Birmingham, Alabama, USA, and in the Landschaftspark near Duisburg in Germany, the former serving as a theater and the latter being used for a variety of recreational purposes, including a climbing wall in the ore store and diving training taking place in one of the now flooded gas holders. However, warehouses, malt-houses, and textile mills are increasingly being converted for housing and there have been some spectacular conversions for retail use, such as the former chocolate factory in Ghirardelli Square in San Francisco. Industrial archaeologists must continue to press for and be involved in adequate archaeological recording of both buildings and their context prior to such conversions; preservation per se needs be selective but preservation by record is essential.

Industrial archaeology is then a discipline in tension which seeks to maintain a balance between investigative techniques which can lead to destruction of sites and the preservation of sites and structures for posterity.

World History

World History