The Middle Kingdom dates from the victory of Mentuhotep II of Thebes over his rivals at Herakleo-polis and the re-unification of Egypt. Initially residing in Thebes, the Twelfth Dynasty (c. 1985-1773 BC) moved to a new capital called Amemenhet Itj-tawj, possibly in an area south of the old residence at Memphis, close to the Fayum Oasis. Archaeologists have yet to find and excavate this new capital. Passing on from father to son, the Twelfth Dynasty stayed in power for almost 200 years. The central administration followed in the footsteps of the Old Kingdom with a vizier at the top, a treasury, a ministry for supervising the harvesting and managing of the crops, a ministry for cattle and fields, and a ministry for labor, responsible for the building programs of the state. The king was still the absolute divine ruler but his legitimacy was based on representative theocracy and not on direct rule as in the Old Kingdom. Foreign affairs were dominated by the conquest of Lower Nubia and various raids into the Levant, which brought back Asiatics as slaves. Asiatics also moved voluntarily to the Nile Delta and settled there. Domestically the Twelfth Dynasty is credited with an irrigation program in the Fayum Oasis for new cultivation. Regarding religion, a new concept of the underworld, the kingdom of Osiris, saw the rise of this god. In addition, the concept of Maat (translated often as order or connective justice), a guideline of how Egyptians should live and treat each other, became popular. A wealth of literary texts was composed during the Middle Kingdom, and many of these were later considered classics. The language of these texts, Middle Egyptian, remained in use for sacred texts until the end of the Pharaonic period.

All the achievements of the Middle Kingdom made it the ‘classical’ Egyptian age that was revered in later periods. Yet the Middle Kingdom ended in fragmentation when the Thirteenth Dynasty had to give way to pressure from the Hyksos, Asiatic rulers in the eastern Nile Delta, and moved their residence to Thebes in the south.

The Mortuary Complex of Mentuhotep II

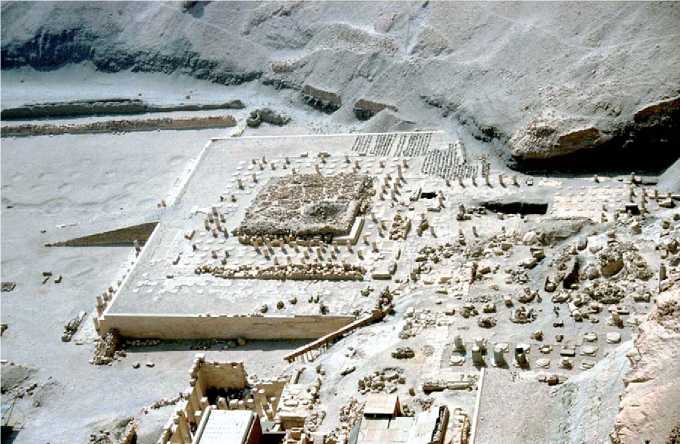

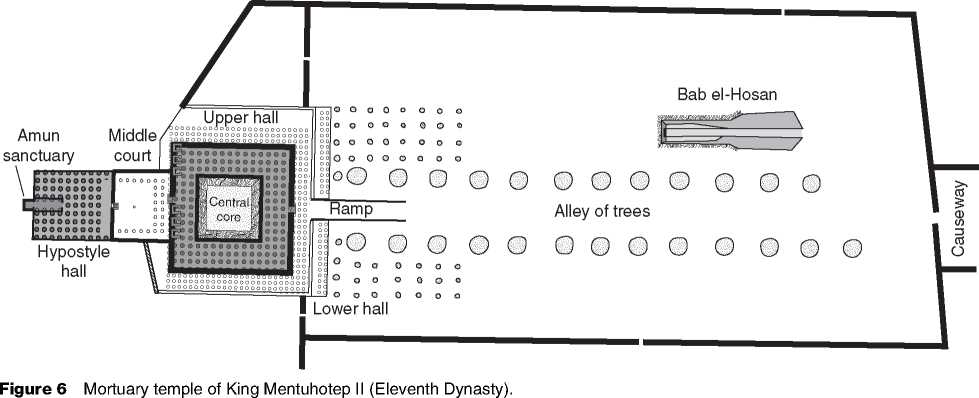

Under Mentuhotep II a unique mortuary temple was erected in the limestone escarpment of Deir el-Bahri on the west bank at Thebes (Figures 5 and 6). The complex once had a valley temple near the edge of cultivation and from there a causeway more than 1 km long led to a huge court in the west surrounded by a sandstone wall. Inside the courtyard, the discovery of the roots of sycamores and tamarisks in tree pits indicates that an alley once existed here. It was

Figure 5 Mortuary temple of Mentuhotep II at Western Thebes (Eleventh Dynasty).

Also in the courtyard that the initial royal tomb, today known as Bab el-Hosan, was found. A ramp at the end of the alley led to a platform topped by a core building and an ambulatory. The core building might have been crowned in different ways. A pyramid (for which there is no archaeological evidence), a mastaba-like structure, or a mound of soil resembling the primeval mound from which the land of Egypt once emerged, are all possible options and would all be in accordance with Egyptian beliefs. A further arrangement of courtyards and a hypostyle hall continued to the west until finally, the sanctuary and the royal tomb itself were cut into the rock escarpment. Foundation deposits in the four corners under the platform and the core building, which consisted of food offerings, ceramic, and wooden models of

People and objects like bread and vessels, as well as mud-bricks with tablets with the royal name on them give an intriguing glimpse into the rituals accompanying the construction of the temple.

Middle Kingdom Pyramids

The kings of the Twelfth Dynasty deliberately repeated the Old Kingdom tradition of pyramid building along the desert edge west of the Nile Valley. The new construction method, however, consisted of a mud-brick core with a grid of stone walls. The finish was still done with limestone casing blocks. Although the new construction method was far more economical, it is no indication that the Egyptian kings could not afford solid stone pyramids. Today the limestone casing blocks have been stripped away and the Middle

Figure 7 Pyramid of King Amenemhat III at Hawara (Twelfth Dynasty).

Kingdom pyramids are in a very bad condition with the mud-brick core exposed to the elements (Figure 7).

The Settlement of Lahun

About 1200 m east of the pyramid of Senusret II (c. 1877-1870 BC), W. M. F. Petrie discovered the remains of a pyramid town called Lahun. A pyramid town is essentially the settlement that housed the workmen building the pyramid complex along with the officials overseeing the work. Subsequently, it became the home for those responsible for the royal funerary cult. Lahun was a planned town with a rigid grid system. It included an enclosure wall and a wall that divided the settlement in half. One side contained about a dozen large houses with as many as 70 rooms and covering up to 3000 m2. The other side had more than 200 houses, but their maximum size was less than 200 m2. This size disparity clearly reflects the hierarchy in the town, with a few elite individuals living in luxury while the majority lived in modest dwellings. Based on the size of granaries at Lahun, a population of up to 9000 persons has been proposed, but according to a papyri archive found at the site which sometimes lists six persons per household, the population might have been much smaller. Lahun is also important for the discovery of Minoan sherds and Egyptian imitations of Minoan pottery.

Nubian Fortresses

In the wake of its aggressive foreign policy in the south, a string of fortifications were built during the Twelfth Dynasty in order to secure trade routes and to protect the border. According to textual evidence,

Egypt built at least 17 military installations starting c. 100 km south of Egypt’s border at Elephantine. Fifteen of these mud-brick built fortresses were excavated during several rescue campaigns. Following the construction of the High Dam at Aswan, the fortresses now lie beneath the waters of Lake Nasser. The forts are all very close to each other, often only 3-10 km away or just lying across the narrow stretch of the Nile. Their proximity to one another made signaling by smoke or beacon quite simple. There were two types of fortresses: first the plain type which had an almost square layout that bordered the Nile on one side. Some of the outer walls, which measured up to 460 x 215 m and were more than 5 m thick, contained towers with loop holes for archers and were possibly topped by crenellations. Inside these mud-brick walls, a system of ditches and ramparts formed the first line of defense around the citadel, which had storage facilities and housing for the soldiers and officials. The second type of fortress was built on granite formations which could not be easily leveled. Thus, they had not a straightforward rectangular layout but possessed a more irregular shape.

World History

World History