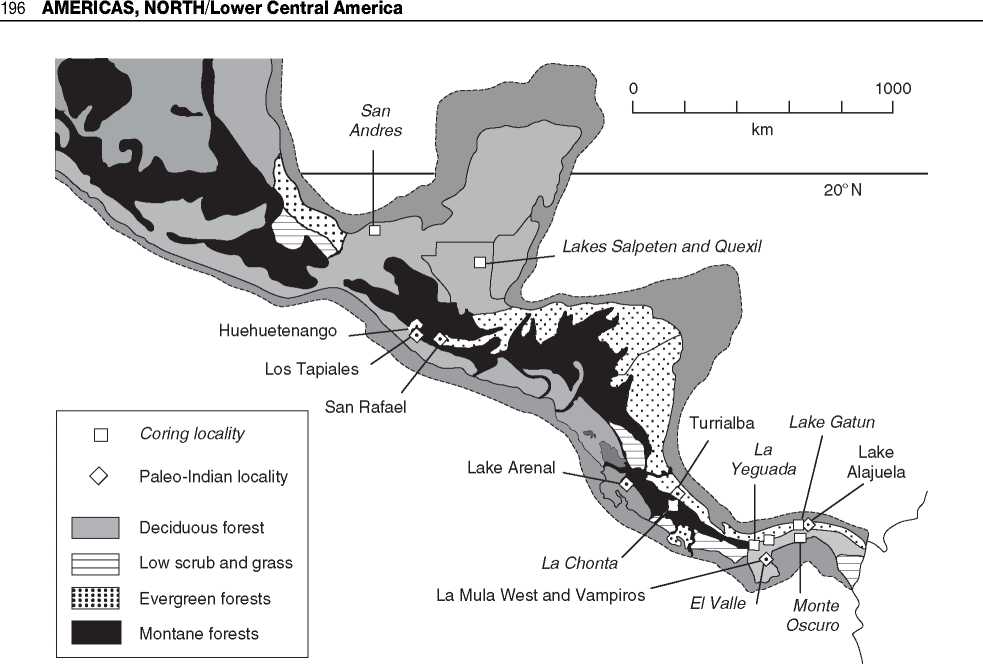

Central America landscapes have changed in many important ways since the first human groups entered the region during the last major glaciation (Figure 3). Temperatures were c. 5-6 °C lower than they are today and rainfall was reduced by perhaps 30-40%. The massive glaciers in the world’s polar regions held enough water to lower sea levels over 100m and expose the continental shelf, which for parts of CA, added significant areas of dry land, particularly along the Pacific site of Panama and the Caribbean side of Belize, Honduras, and Nicaragua. Reconstruction of Late Pleistocene vegetation at coring localities in Panama (La Yeguada, El Valle, Monte Oscuro, and Gatun Lake), Costa Rica (La Chonta), and the Peten region of Guatemala (Lakes Salpeten and Quexil) indicates that areas now receiving in excess of c. 2000 mm of rainfall annually would have been forested during the last glacial stage, whereas areas with annual rainfall below c. 2000 mm were likely to have had open savanna or low scrub vegetation. These more open formations would have been located on the Yucatan Peninsula, including the Peten and Belize, along the Pacific coastal plain from El Salvador to northwestern Costa Rica, and the Pacific coastal plain along Panama Bay. Still in all, large areas on the Pacific side of CA receive over 2000 mm of rain annually, including an area stretching from central Costa Rica to Central Panama and the area near the Colombian border. Most of the Atlantic watershed of CA receives well over 2000 mm of rain annually. While it seems clear that the late glacial landscape of CA contained more extensive open habitats than at any time during the Holocene (that is, until massive forest clearing for cultivation was underway), it was still a largely forested landscape.

The Late Pleistocene landscape in CA was populated by at least 15 genera of large herbivores that did not survive to see the Holocene. These include the mastodon-like gomphotheres (Cuvieronius tropicus and Haplomastodon), mammoth (Mammuthus), megalonychid and megatheriid giant ground sloths, including the huge Eremotherium, glyptodonts (Glyp-todontidae), giant armadillos (Pampatherium and Chlamytherium), a horse (Equus (Amerhippus)), the rhinoceros-like Toxodon, the camel-sized Macrau-chenia, Paleolama, giant capybara (Neochoerus), flat-headed peccary (Platygonus), and bear (Arcto-dus). Included in this list are browsers, grazers, and omnivores adapted to a range of forest, forest edge, and open thorn scrub/savanna environments. While none of these taxa has been found in association with human artifacts in CA (bone was not preserved in the sites excavated to date with Late Pleistocene cultural

Figure 3 A map showing the reconstructed vegetation of Central America during the Late Pleistocene and the coring localities that provided the information for this reconstruction. The location of major Paleoindian localities are also indicated. Adapted from Ranere AJ and RG Cooke (2003) Late Glacial and Early Holocene occupation of Central American tropical forests. In: Mercader J (ed.) Under the Canopy. The Archaeology of Tropical Rain Forests, pp. 219-248. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. Reproduced with permission.

Deposits), some have been found in archaeological sites of northern South America (see Americas, South: Northern South America). At the site of Tibitti in the Bogata Basin, Cuvieronius, Haplomastodon, and Equus (Amerhippus), as well as extant fox (Cer-docyon) and white-tailed deer (Odocoileus), were associated with human activities 14C dated to 11740 ± 110 BP (11638 BC). Haplomastodon was found in association with an El Jobo lanceolate point at Taima-Taima, Venezuela, dated c. cal 13 400BC. The same layer as the mastodon and El Jobo point also yielded glyptodont, mylontid sloth, horse, bear, and felid remains. Elsewhere in Venezuela (at the site of El Vano), El Jobo points have also been found in direct association with the giant ground sloth Eremotherium rusconii.

We can say very little about the nature and timing of the earliest migrants into and through the Central American Isthmus; those who were ancestral to the groups documented further south in sites like Monte Verde in Chile, Taima-Taima in Venezuela, and Tibittf in Colombia, among others. There are no firm archaeological sites that reflect the presence in CA of any groups older than the Paleoindian Clovis populations.

Diagnostic Paleoindian fluted points of the Clovis and Fluted Fish-tail types have only been found in two stratified sites in CA that have reported radiocarbon dates, Los Tapiales in the Guatemalan Highlands and Cueva de los Vampiros in the Pacific coastal plain of Panama. Los Tapiales is an open-air site located at an elevation of 3150 m in what is currently an alpine meadow. 14C dates of 11170 ± 200 BP (c. cal 11200BC) and 8810 ± 110BP (c. cal 7960BC) bracket deposits from which 100 tools and nearly 1500 flakes were recovered, including a fluted point base and a channel flake. The excavators, Ruth Gruhn and Alan Bryan, view the occupation as short term and believe that the 14C date of 10 710 + 170 BP (c. cal 10 700 BC) is the best estimate of its age. At Vampiros, cave deposits bracketed between 14C dates of

11550 ± 140BP (c. cal 11460 BC) and 8970 ± 40 BP (c. cal 8150 BC) contained the blade portion of a Fluted Fish-tail point and overshot thinning flakes characteristic of Clovis-reduction techniques (but not Fish-tail-reduction techniques). Similarly aged deposits have been excavated at three other Central American sites; La Piedra de Coyote (14C dates of 10650± 1350BP (10250BC) and 10020±260BP (9680 BC)), located in the Guatemalan Highlands near Los Tapiales, Aguadulce Shelter (14C dates of 10 725 ± 80BP (c. cal 10 825BC), 10 675 ± 95BP (c. cal 10785BC) and 10529 ± 284BP (c. cal 10490BC)), located in the coastal plain of Central Pacific Panama near Vampiros, and Corona Shelter (14C date of 10440 ± 650BP (c. cal 10115BC)), located in the foothills of Central Pacific Panama. Although no clearly diagnostic tools were recovered, all three sites yielded bifacial thinning flakes consistent with those produced in manufacturing fluted points.

Although undated, a number of Clovis and Fluted Fish-tail points have been found in Central America, some as part of surface site assemblages and some as isolated finds. The site of Turrialba (also known as Finca Guardiria), at 10 ha in area, is by far the largest Paleoindian site known for CA. It is located at an altitude of c. 700 m on terraces of the Reventazcon River in the Atlantic watershed of Costa Rica. The region receives 4000 mm of rain annually and would be covered in evergreen forest if not for human intervention. The entire site area has been cultivated and all of the over 28 000 flakes and tools have been recovered from the surface or the plow zone. Large numbers of fluted Clovis points were recovered, as well as bifacial preforms and other tools often found with other fluted point assemblages, that is, snubnosed keeled scrapers, end-scrapers with lateral spurs, burins, and large blades.

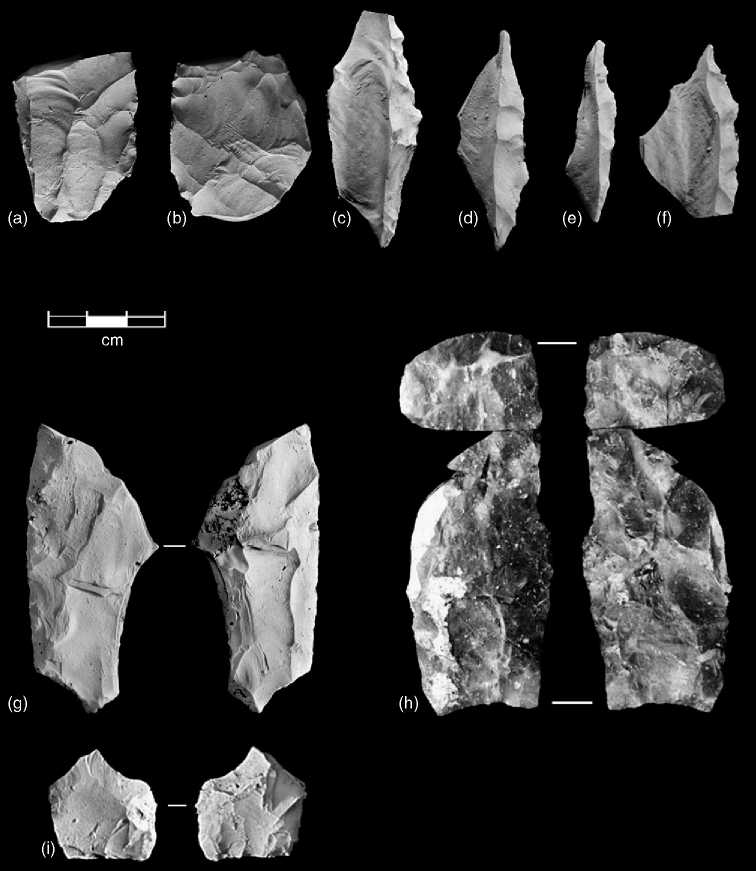

Another important Clovis site is the La Mula West workshop, Central Pacific Panama, where erosion has left workshop debris and the rare finished tools exposed on the ground surface or buried in reworked deposits. Over 80 biface fragments were recovered from the site, including 12 basal fragments that had been either fluted or basally thinned. Spurred end-scrapers, burins, gravers, and blades were recovered at La Mula West as well. The only near-complete specimen recovered would be lost in a collection of early North American Clovis points. The lithic reduction sequence reconstructed on the basis of the broken bifaces and manufacturing debris, including a number of overshot flakes and hundreds of thinning flakes, is nearly identical to the sequence reported for North American Clovis workshops. Although there is no direct date for the La Mula West assemblage, 15 years before its discovery, an isolated hearth 14C dated to 11300 ± 250 BP (c. cal 11215BC) was found eroding out of sediments near the site. This seems an appropriate age for an assemblage that shares the same lithic reduction sequence and projectile point form as the early Clovis assemblages in North America (Figure 4).

Two additional sites in Panama have yielded bifaces and workshop debris that can be assigned to the Paleoindian period. One, the Neito quarry/ workshop, is located in the Azuero Peninsula west of La Mula West and contains the same translucent chalcedony material preferred by the La Mula West Clovis flintknappers and evidence of similar reduction techniques. The second site, the Westend workshop, is located in the Chagres River drainage near the Panama Canal on the shores of an island in Lago Alajuela (Madden), an artificial lake that stores water to supply the operation of the Panama Canal locks. At low water, workshop debris covering an area c. 1 ha in size is exposed on the eroded surface. Although thousands of thinning flakes are present (most with small, heavily ground platforms) only two preforms and no finished points were recovered. However, elsewhere on eroded shorelines of Lago Alajuela, six Fish-tail points and one ‘waisted’ Clovis point have been picked up. The preponderance of Fish-tail points in the lake basin and the absence of overshot flakes in the Westend assemblage indicate that Fish-tail points and not Clovis points were the desired end product.

Additional isolated fluted points of both Clovis and Fish-tail varieties have been found in a number of different contexts in CA, including the Belize Lowlands, Guatemala Highlands, both the lowlands and highlands of Costa Rica, and the foothills and coastal plain of Pacific Panama. While Paleoindian sites and isolated finds are relatively few in number, they are found in a wide range of geographic and ecological settings. Paleoindian lithic remains have been found above the Late Pleistocene tree line (Los Tapiales and Piedra de Coyotes) in highland Guatemala, in montane closed-canopy forests elsewhere in Guatemala (Guatemala and Ocozocoautla valleys) and Costa Rica (Turrialba and the Arenal region), in lowland closed-canopy forests (Lago Alajuela in the Chagres Basin), and in open savanna/thorn scrub lowlands (Belize, northwest Costa Rica, and Central Pacific Panama). Paleoindian groups were clearly able to move about through the entire range of geographic and environmental settings found in CA during the Late Pleistocene. This ability may have more to do with an emphasis on hunting rather than on gathering by these populations; Clovis and Fish-tail points are, after all, hunting weapons and no specialized plantprocessing tools have been found at Paleoindian sites. Hunting techniques are relatively easy to transfer from one environment to another and meat eating is not a hazardous undertaking. On the other hand, learning what plants can be safely consumed in newly encountered environments, or learning how to render the plants safe for human consumption can be a timeconsuming process. The picture that is emerging of CA Paleoindians is one of small mobile groups moving though a range of environments in pursuit

Figure 4 Artifacts from the Clovis workshop of La Mula West, Panama: a and b, point preforms broken in manufacture; c-f, overshot flakes, a characteristic feature of Clovis point manufacture where the opposite side of the preform is removed in the thinning process; g-i, late-stage fluted preforms broken in the manufacturing process.

Of game but perhaps tethered to high-quality sources of stone for manufacturing their skillfully made projectile points.

World History

World History