There are a few objects in Iron Age art which are of outstanding significance in terms of an association between animal iconography and religion. One group consists of cult cauldrons, great vessels which were undoubtedly of ritual rather than of secular use. These cauldrons are from Denmark, but the imagery owes a great deal to Celtic traditions. The huge Rynkeby Cauldron is decorated with the image of a human head flanked by two bull-heads; an inner plate depicts two wild animals, one on either side of a triskele.44 The Bra Cauldron is fitted with suspension-rings ornamented with birds' heads; the handle-mounts are in the form of bulls (figure 2.6).45 But the most spectacular animal-decorated cauldron is that from Gundestrup, a large, silver, once-gilded, vessel whose inner and outer plates, decorated by many different artists, are covered with repousse iconography of gods, plants and beasts of all kinds, both real species and ones which owed their form to the imagination of their creators (figure 6.16).46 The cauldron was probably made sometime between the second and first centuries BC: its iconography shows mainly Celtic influence, but the most likely place of manufacture is eastern Europe - Romania, Hungary or Bulgaria. The 'Gundestrup Zoo' which adorns the five inner plates is fascinating in its variety and in the clear importance of zoomorphic imagery. Stags, bulls, gods and boars are among the temperate European species represented, but there are also elephants flanking the figure of a goddess;47 leopards accompany the Celtic sky-god;48 and a trio of winged griffins gambol beneath him (figure 6.17). Many of these exotic creatures are related to the fantastic beasts belonging to the repertoire of silversmiths living in the Lower Danube. Bulls figure very prominently: on one plate are three identical bulls each threatened by a hunter with a sword and a hound above and beneath each bull (figure 5.3).49 The baseplate of the cauldron features an enormous dying bull, perhaps a wild aurochs, which sinks to its knees before the onslaught of a hunter and his dogs (figure 5.1). The killing of the bull seems to be important, perhaps as an act of sacrifice or as a representation of a myth of death and re-creation, similar to that of the Persian Mithras, who slew the divine bull so that the earth would be nourished by its blood. The bull imagery is very persistent on this cult vessel: the sky-god with his solar wheel is attended by a small human figure who wears a bull-horned helmet with knobs on the end of the horns. These knob-horns recur elsewhere in bull images, for example on the firedog at Barton, Cambridgeshire (figure 2.23); the figurine from Weltenburg near the oppidum of Michelsberg in Bavaria; and on the bull-heads on the bronze rein-ring at Manching (figure 2.4). Megaw has suggested that the knobs on bull-horns may be associated with stock management and the use of knobs in farming.50 But, to my mind, this is unlikely, especially in view of the horns on the Gundestrup figure. In any case, there is no evidence for the use of such knobs in Celtic husbandry. I think that such horn terminals are more likely to relate to some form of symbolism, perhaps related to some 'defunctionalizing' device, introducing non-realism to the image in order to render it appropriate as a sacred motif.51

Some of the zoomorphic imagery at Gundestrup has very definite divine associations, which may be linked with the unequivocal religious iconography of Romano-Celtic Europe. Such is the monstrous ramheaded serpent, which appears on more than thirty monuments or figurines in Gaul and Britain. This hybrid creature, which combined the

Figure 6.16 Gilt silver cauldron decorated in repoussee with mythological scenes, second to first century BC, Gundestrup, Jutland, Denmark. Diameter: 69cm.

Paul Jenkins.

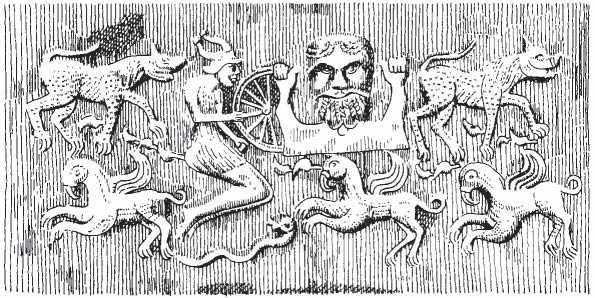

Figure 6.17 Inner plate from Gundestrup Cauldron, depicting wheel-god, a being with a bull-horned helmet, ram-horned snake, leopards and winged mythical creatures. Paul Jenkins.

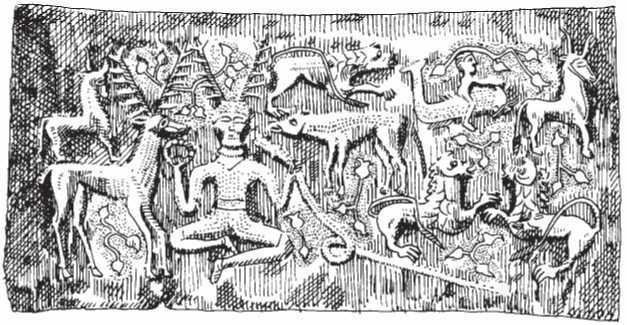

Fertility symbolism of the ram with the chthonic and regenerative imagery of the snake (see chapter 8), occurs three times on the Cauldron, once on the same panel as the wheel-god, a second time in company with the stag-god Cernunnos. The latter association is particularly significant, since it is with Cernunnos that this idiosyncratic beast appears on the monuments of Romano-Celtic Gaul.52 Cernunnos is the stagantlered god, lord of animals, nature and abundance. At Gundestrup, he sits crosslegged, wearing tall antlers on his head, wearing one torc and holding a second (again a recurrent and distinctive feature of his symbolism in Gaul), and grasping a ram-horned serpent in his left hand (figure 6.18). Beside him and facing him is his stag, who has identical antlers; the close affinity between god and animal is very clearly reflected, and the stag may even be Cernunnos in non-human form. With the god also are two bulls, a wolf, two lions, a boar and a dolphin ridden by a boy. This early image of Cernunnos can be related to another depiction, far away from Denmark, at Camonica Valley in north Italy, where a rock carving dating to the fourth century BC depicts a standing antlered anthropomorphic figure, with two torcs and a horned serpent (see chapter 8). The third depiction of the ram-horned snake at Gundestrup appears on the Celtic army scene depicted on one of the plates (figure 4.5).53 This comprises a curious set of images which includes a great tree or branch set horizontally along the plate, apparently supported by the tips of six spears carried by marching infantrymen beneath it. Above the tree, at the top of the plate, ride four cavalrymen led by the horned serpent. Behind the horsemen stands a god, apparently dipping a human sacrificial victim into a vat, perhaps to bless the battle about to take place. The zoomorphic imagery of this plate is intense: in addition

Figure 6.18 Inner plate from Gundestrup Cauldron, depicting the antlered Cernunnos as Lord of the Animals. Height of plate: 20cm. Paul Jenkins.

To the snake and the cavalry horses, one of the horsemen wears a horned helmet, a second has one with a boar-crest and yet another sports a bird perched on his helmeted head. The last infantryman below the tree carries what appears to be a sword, rather than a spear like his companions, and he alone of the foot-soldiers has a boar-crested helmet, while the others are bareheaded. Facing the first foot-soldier is a leaping dog, and behind the soldiers march three more infantrymen bearing open-mouthed boar-headed carnyxes.

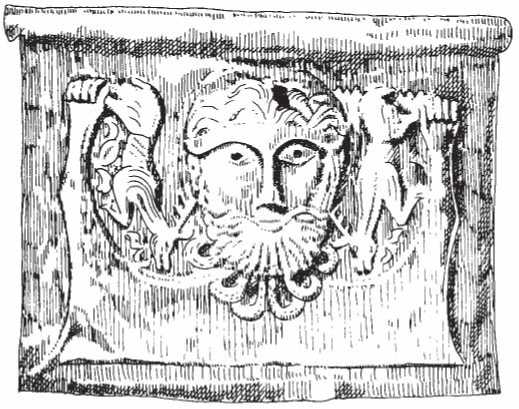

Whilst it is the five inner plates on which the greatest variety of divine and zoomorphic imagery is to be found, the seven outer panels of the cauldron are not devoid of animal iconography. These outer plates possess figural decoration very different from the narrative, mythological scenes of the inner panels. Each bears a depiction of a human bust, four male bearded heads and three female. The male figures54 each have large heads and diminutive upthrust arms: clasped in the hands of two of them are images of animals, which must be meant to represent effigies, perhaps of wood, rather than living (or dead) beasts (figure 6.19). One of the figures holds two antlered stags, the other a pair of curious seahorse-like creatures, with horses' manes and front legs but with wings on their backs, long tails and no hind legs. Beneath the god's shoulders are two small 'acrobats' with a long, two-headed boar or dog stretched between them. A third 'male' panel shows a god holding two small human effigies by one arm each and these humans in turn brandish smaller boar-figures, balanced on their hands; a dog and a winged horse prance beneath the humans. The effigies held by these male figures are strongly reminiscent of the cult imagery of the Viereckschanzen of Fellbach-Schmiden near Stuttgart (figure 2.13).55 This consisted of a square ritual enclosure surrounding a sacred well, from which came oak carvings of animals, including a stag. There are carved hands holding the creatures, as if they were once grasped in precisely the same manner as portrayed on the cauldron. According to dendrochronological evidence, the oak from which the Fellbach Schmiden figures were made was felled in 123 BC. The three 'female' panels carry less zoomorphic symbolism but some is present:56 on one, the goddess is accompanied by a small man, embracing or wrestling with a large animal, perhaps a cheetah.57 On a second 'female' plate, another goddess has one arm upheld, a tiny bird perched on her thumb. Above are two eagles (recalling the two on the Besseringen neckring); beneath her breast is a small dog or boar lying on its back as if in play.

It is quite clear that the Gundestrup Cauldron depicts some kind of complicated mythological narrative, perhaps an epic of creation or an account of the activities of a Celtic pantheon. We will never fully understand it; all we can do is to examine links between its iconography and the Celtic imagery known from other sources, and to note the sheer abundance of animals, a veritable zoo (or safari park) reflecting so many species both familiar and strange to the Celtic world.

A completely different but equally important piece of zoomorphic imagery which dates to the early Iron Age is the Strettweg cult wagon from Austria, made in about the seventh century BC. It comes from the

Figure 6.19 Outer plate of Gundestrup Cauldron, depicting a god holding animal effigies. Paul Jenkins.

Burial of a man who was cremated and his remains interred with an axe, a spear and three horse-bits, beneath a mound. He was a warrior of note, a knight, and the presence of this unique wagon-model must imply his high status. The central figure on the wheeled platform is a goddess, bearing a shallow dish above her head. Before and behind her are two groups, each consisting of two women with a large-antlered stag between them whose antlers they hold, and behind them are a man and a woman, she with earrings, he with an axe and an erect phallus. Flanking these humans and stags are pairs of mounted warriors with spears, shields and pointed helmets (frontispiece).58 The wagon frame bears pairs of bulls' heads at both front and rear. The Strettweg group appears to represent some kind of cult, perhaps involving a ritual hunt or sacrifice of a stag to the goddess, who possibly raises a dish full of its blood in acceptance of the offering. The dead chieftain in whose grave the cult wagon was placed may even have taken part in such rituals himself: he may be depicted as one of the axemen or a horseman; he was, after all, sent to the Otherworld with an axe and horse-trappings.

World History

World History