Considering the geographical barriers described, the question arises as to whether they went along with cultural isolation. At a first glance, the number of archaeological assemblages, mostly pottery, supports this idea. The wide distribution of certain styles, however, points to a different direction. Its implications are difficult to assess since unlike ‘imported’ exotic commodities and materials, such as sea shells, semiprecious stones, and metals which were exchanged, looted, or paid as tribute, and even unlike the copying of new technologies, the adaptation of pottery designs, figurines, or other artifact styles inherits a semantic dimension which is difficult to assess (see Pottery Analysis: Stylistic).

With regard to the amount and nature of archaeological data, we have to define descriptive units. The Balochistan Tradition is the overarching geographically and temporally continuous heuristic system composed of multilinear archaeological entities which are linked in space and time. ‘Eras’ are developmental stages, such as food-producing and regionalization. A ‘phase’ combines a number of cultural complexes within a broadly defined region and time trajectory. ‘Cultural complexes’ or ‘horizons’ are recurrent configurations of features within archaeological assemblages, at present mostly pottery styles. Per definitionem they reflect human abilities, requirements, stylistic, and technological choices and preferences, but are not a priori considered to represent particular social or even ethnic groups. Their distribution patterns form the cultural landscape and outline ‘mental’, or conceptual, maps. Recent research has shown that these styles and horizons are still badly defined and dated which makes the reconstruction of these processes through time and the assessment of interaction and its impact on development difficult. Accordingly, we refrain from merging styles and horizons into larger units that have little analytical value, but rather discuss the smaller entities, paying tribute to regional stylistic diversity notwithstanding shared features.

Early Food Producing Era: First Settlements (Mehrgarh I, II, KGM I, II, Anjira I, II, Miri I?)

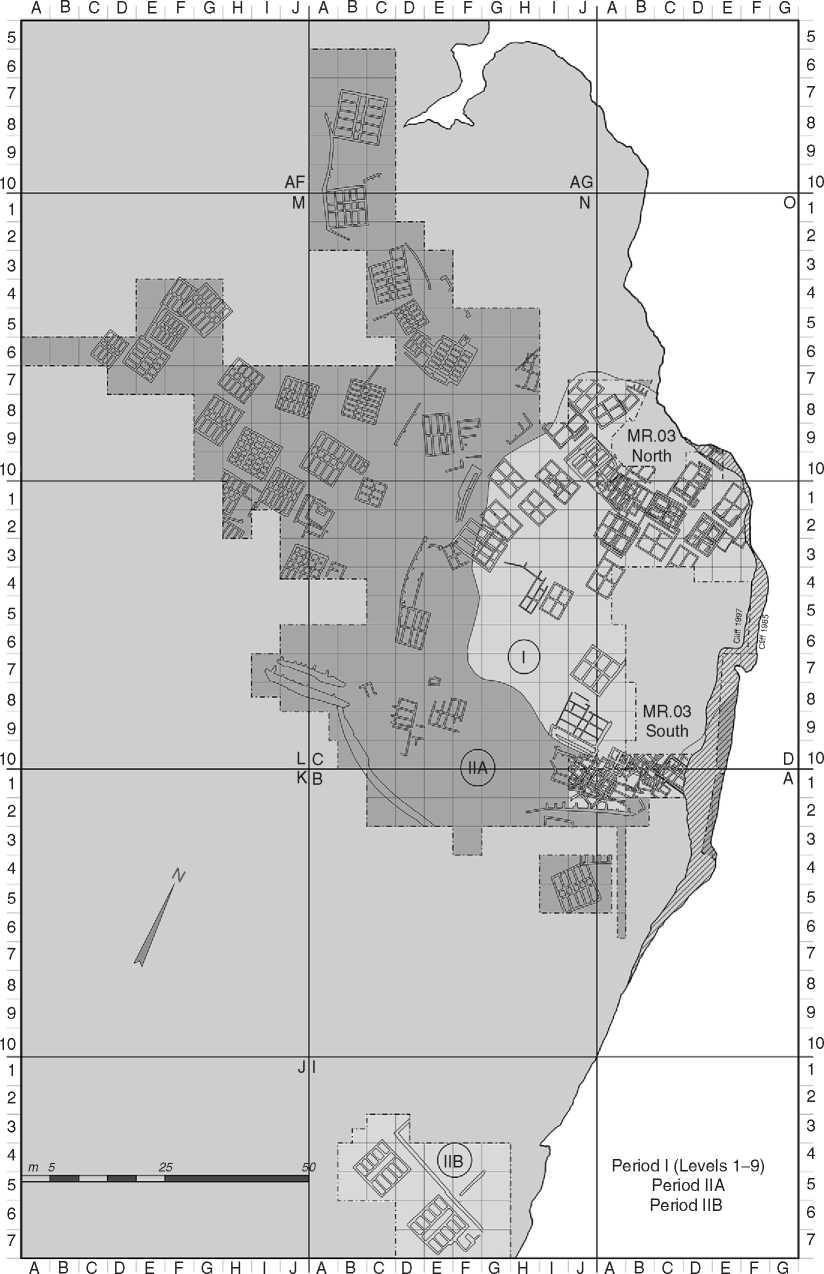

After around 7000 BC in northern Baluchistan, mobile hunters and gatherers had gradually settled down. The adaptation of einkorn, emmer, wheat, and barley as staple crops, and a successful animal husbandry (cattle, goat, sheep), facilitated the development and growth of villages (see Animal Domestication ; Plant Domest ication). Mehrgarh is the type site for understanding the formation of a tradition that was to last for nearly seven millenniums (Figure 2). Seven-meter high deposits and nine building levels for the Neolithic Periods reveal alternating shifts of the habitation and cemeteries over a long time. Altogether, 77 well-planned houses with two, four, and later six rooms and separate communal storage facilities were excavated (Figures 3 and 4). 320 burial chambers contained ochre-covered bodies of all sexes and age classes (Figure 5). On 11 out of 225 examined bodies, signs of ancient dentistry were found. Elaborate shell, stone, and copper ornaments, lithic objects, sometimes bitumen baskets, human figurines, and goat sacrifices accompanied the dead. While in Period I, heat-treated steatite, turquoise and lapis lazuli beads, and shell bangles probably arrived as finished objects, several workshops and wasters indicate an intensive local production during Period II, marking the beginning of technologies that remained characteristic throughout time. Pottery appears for the first time in Period II, along with stone vessels, but it is in Period III that these technologies were greatly advanced.

Incipient farming and animal husbandry, and the first introduction of pottery were also noted at KGM near Quetta and, albeit at a later stage, further south at Anjira. The oldest settlements in southeastern Baluchistan date to the later fifth millennium. While in northern Baluchistan an interaction network developed, the picture in Makran is different. The lowermost aceramic levels at Shahi Tump I and a few other sites are, if at all, related to the Iranian Plateau. The faunal material indicates a change in subsistence strategies after Period I, and further research will show whether this site belongs to the Early Food Producing Era.

Incipient Regionalization: The Expansion of Settlements. The Kile Ghul-Mohammad/Togau Horizon (Mehrgarh III, KGM III, Anjira II, Sohr Damb I?, South Eastern Baluchistan I, Makran: Miri I?, II, Mundigak I-II)

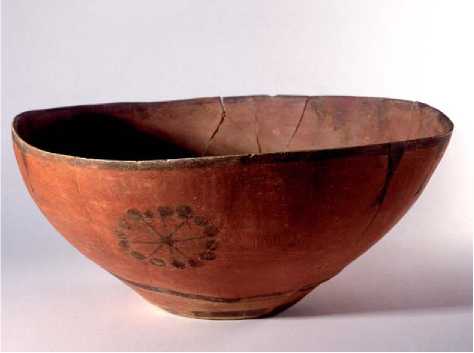

The time of Mehrgarh III (late fifth and early fourth millennium) was marked by a considerable rise in the number of settlements in northern Baluchistan. Many were new foundations, indicating a population growth that reflected the success of subsistence economies. Settlements now also appeared in central and southeastern Baluchistan (Adam Buthi, Niai Buthi). Some sites are small (<1 ha), others, including Sheri Khan Tarakai in the Bannu Basin, are 16-21 ha large. At Mehrgarh, Period III pottery (Figure 6) was scattered over about 100 ha, but the area was probably not inhabited at the same time.

This development was accompanied by a marked increase in the manufacture and varieties of goods produced. The raw materials processed in a bead workshop in Mehrgarh III include resources that are not locally available, such as turquoise, lapis lazuli, agates, jasper, marine shells, and copper. Despite an increased production, the number of grave goods decreases further, particularly in male burials, a shift that, along with the absence of ochre treatments and partial or secondary burials, reflects a change in the conception of death and afterlife.

The introduction of the potter’s wheel and high temperature updraft kilns predate the first appearance in Central Asia by almost 1000 years. Large quantities of a very well-fired, thin-walled, red-slipped and black-painted pottery were now produced. These KGM, Togau, and related types are truly amazing in terms of technology. Their distribution extends from northern and central to southeastern Baluchistan, the Bannu Basin, Mehrgarh, Mundigak I, and Amri in southern Sindh. One motif of the Togau painting style as defined by B. de Cardi characterizes stylistic development from c. 4000 BC to the mid-third millennium: a row of stylized caprids (Togau A), subsequently reduced to the forepart (Togau B), a hook (Togau C, D) and, in southeastern Baluchistan, to a mere stroke (Togau E). Recent excavations at Sohr Damb/Nal have shown, however, that its use as a chronological marker is problematical.

The tombs of Period I at Sohr Damb contain remains of multiple fragmentary burials, accompanied by pottery vessels, carnelian, agate, lapis lazuli,

Figure 3 Mehrgarh, Plan of MR3 Periods I-IIB. Courtesy, French Mission to Mehrgarh, C. Jarrige. © 2007 Dr. Ute Franke-Vogt. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Figure 4 Mehrgarh, view of houses (MR3, levels 4-9). Courtesy, French Mission to Mehrgarh, C. Jarrige.

Figure 5 Mehrgarh IB: burial, with basket. Courtesy, French Mission to Mehrgarh, C. Jarrige.

Figure 6 Mehrgarh: bowl from Period III. Courtesy, French Mission to Mehrgarh, C. Jarrige.

And steatite beads, shells with red pigment, grinding stones, and stone weights (Figure 7). Togau D bowls are standard inventory, but they are associated with Togau A-C and even Togau E bowls, KGM, and Kechi Beg (hereafter: KB) vessels (Figures 8 and 9), styles previously considered to represent development through time. The use of white pigment provides a link to the Bannu Basin and Punjab, but the chronological frame for this ware is not well established. C14 dates are not yet available, but parallels with Mehrgarh III-IV and Miri Il-IIIa point to a date from c. 3800 to 3300 BC. The dancers on the small bowl from Sohr Damb (Figure 10) have a close parallel at Mehrgarh III, but also resemble the Sialk III painting style from the Iranian Plateau (late fifth/early fourth millennium BC).

Figure 7 Sohr Damb/Nal: tomb 739/740, Period I. DAI, Eurasien, Ute Franke. © 2008 Dr. Ute Franke-Vogt. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Figure 8 Sohr Damb/Nal: pottery from tomb 711, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Period I. DAI, Eurasien, Ute Franke. © 2008 Dr. Ute Franke-Vogt. Published by

In Makran, the settlement and cemeteries of Miri Period II date to the first half of the fourth millennium BC (Figure 11). The bodies were treated with ochre, buried on a mat or wrapped in cloths. Grave goods include stone and a remarkable variety of metal objects, for example, axes, spearheads, mirrors, and tools, some of them made of pure copper. The use of almandine garnet for bead making indicates advanced craftsmanship since it is a very hard material to work and elsewhere attested only at Mehrgarh III. Likewise exceptional are objects made from sea shells and fish bones (Figure 12). The graves have

No pottery, but the assemblage from the habitation is still rather isolated from the rest of Baluchistan. Terracotta bulls with and without humps match the faunal record that shows a predominance of cattle and caprines. This occupation is compared to chal-colithic Iran, Susa I, Tall-I Bakun, Sialk II, Tappe Hissar IA-C, and Susa I, while links to Tappe Yahya V are few.

The wide distribution of objects, goods, and technologies witnesses the movement of people through a large area. Whether styles traveled with or without their semantic value is open to question.

Figure 9 Sohr Damb/Nal: KB beakers from tomb 740, Period I. DAI, Eurasien, Ute Franke. © 2008 Dr. Ute Franke-Vogt. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Figure 10 Sohr Damb/Nal: Bowl with ‘dancers’, Tr. IIIb, l. 749, Period I. DAI, Eurasien, Ute Franke. © 2008 Dr. Ute Franke-Vogt. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Notwithstanding expanding interaction, differences in style, economy and, for example, burial customs imply persistent local patterns.

Widening Horizons in a Patterned Landscape (Mehrgarh IV-VI, KGM IV/Damb Sadaat I-II, Anjira II-III, Sohr Damb I-II, South Eastern Baluchistan II, Makran Miri IIIa, Shahr-e Sokhta I, Tappe Yahya IVC, Mundigak II-III)

The subsequent period corresponds to Mehrgarh IV-VI, dated to c. 3500 - 2900/2800BC. At the beginning of this time, the habitation was moved for the last time. A significant change was the abandonment of communal in favor of individual storages within now larger houses. Irrigation channels facilitated an intensified cultivation of wheat and other plants needed to feed a growing population. The shift from cattle to sheep and goat keeping possibly indicates the integration of larger grazing areas and wider seasonal movements of people.

At Sohr Damb/Nal, Period II is marked by many changes. The typical Period I pottery is replaced by the buff Nal ware, although highly fired, black-slipped KB white-on-dark slip bowls, which form c. 15% of the inventory, reveal that firing technology survived a hiatus evident in stratigraphy, architecture, and burial customs. These vessels carry the earliest graphemes known in this region, one or two engraved or painted in white signs. The houses are small, but

Figure 11 Shahi Tump Tr. IV, period II architecture. Courtesy, French Mission to Makran, R. Besenval.

Figure 12 Shahi Tump, period II, mother-of-pearl fish. Courtesy, French Mission to Makran, R. Besenval.

Well equipped with kitchen utensils and installations for food preparation. Among these tools, simple bull clay figurines and personal ornaments are most frequent. The tombs contain just one skeleton in a flexed position, and the grave goods comprise of only a few pottery vessels and personal ornaments. The same Tendency toward lower-status objects in tombs was observed at Mehrgarh III. The only later cemetery found at that site was devoted to infants and had almost no grave goods.

In Makran, the Shahi Tump Period IIIa, dated to 3500-3000 BC, yielded a rich funerary culture with pottery, shell containers with ochre, stone vessels, beads, and copper seals, associated here, as elsewhere, predominantly with female bodies, and a 15 kg copper weight inlaid with shell and carnelian, similar in shape to stone weights from Sohr Damb/Nal Period I (Figure 1 3). The appearance of Togau and Bichrome sherds and the use of white pigment reflects links with the rest of Baluchistan. Still, comparisons with sites in Iran (Susa Illa, Sialk IV.2, Tall-e Iblis IV-VI) are stronger. Shell bangles with a ridged decoration have almost identical counterparts in a late fourth/early third millennium tomb at Sarazm in Tadjikistan. Forty thousand heat-treated steatite beads made with a technology known in Baluchistan since early Mehrgarh were also found in that tomb, showing that interaction started earlier and was much more extensive than previously thought. At the same time, the discovery of beveled-rim bowls from layers just above manifests the presence of features that hallmark the proto-Elamite horizon in Iran (see below).

The expansion of settlements, their further growth in number and size, the emergence of monumental architecture, perimeter walls, platforms, seals, and first graphemes, advanced technical diversity and craft specialization indicates an increasing economic, cultural, and social complexity. A similar development is witnessed in the eastern lowlands, where the spread of certain pottery types and other features - first the Hakra and Ravi wares in Punjab and, from c. 3000 BC onward, of the Kot Diji horizon - indicates an increased mobility between the highlands and the plains.

Another hallmark of this time is the appearance of a large variety of pottery styles, such as KB, Togau C/D, Quetta, Nal, and gray wares. They link Baluchistan (Kacchi Plain, Quetta, Zhob, Loralai, Pishin, central and southern Baluchistan) with the Bannu Basin, Sindh, and beyond. Yet, the lack of stratified Assemblages that are large enough to account for functional variation, hampers patterning their temporal and spatial distribution, a preposition to the formulation of generic relationships.

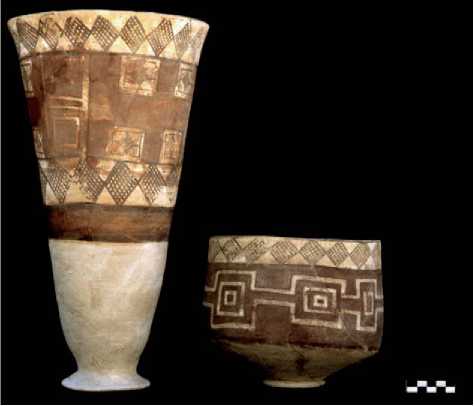

The ‘Kechi Beg horizon’ comprises a number of pottery styles discovered by Fairservis and de Cardi between Quetta and Kalat, and subsequently at Mehrgarh. Three of the nine wares are considered to be horizon markers. KB black-on-buff slip (MR V) shares many motifs with KB bichrome that has a very

Figure 13 Shahi Tump, period Illa: burial with copper weight. Courtesy, French Mission to Makran, R. Besenval.

Delicate black design and a red band or infill painted on buff (Figure 9) , while the additional use of white is only attested at Mehrgarh (Figure 14). At Mehrgarh (IV, V) and KGM (IV) it occurs stratigraphically later than KGM and Togau A-C pottery, but these types overlap at Surab (Surab Il. i = Anjira III). Despite differences in fabric, the fine brush painting and patterns such as hatched lozenges and ‘ladders’ link this pottery with Amri Period I in Sindh. The typological and chronological range of this type is not defined well enough to understand its genesis and spread, not to speak of regional variants and their development through time. At Sohr Damb, it co-occurs with KGM-pottery in Period I, but is absent in Period II, although KB white-on-dark slip vessels are common, indicating that not all KB types are contemporary.

Although, as discussed above, the Togau C/D ‘bowls’ with the stylized hook pattern appear already in Sohr Damb Period I, they are nevertheless a significant marker of the early third millennium sites. They were found at Mehrgarh V-VI, at most sites in central and southeastern Baluchistan (Anjira II-III, Balakot IA/B), in the piedmont area in eastern Sindh, at Amri I, and Miri Qalat IIIa. Most probably, this ware originated in the central highlands and spread from there to, for example, Kirthar Piedmont. There, it co-occurs with Nal and late Quetta pottery, but it was not found at the Quetta sites and Sohr Damb II.

The ‘Quetta horizon’ as defined by Piggott and Fairservis is marked by a buff or red ware painted in black with a fine brush with complex geometric patterns based on black-white contrasts and arranged in friezes that cover large parts of the body (Figures 15-17). This ‘geometric’ pottery occurs at Damb Sadaat in Periods II and III, together with

Figure 14 Mehrgarh, period V, polychrome beakers. Courtesy, French Mission to Mehrgarh, C. Jarrige.

Figurative and floral motifs, simple linear designs, and unpainted vessels. It is the hallmark of a horizon that extended as far as Gumla II, Namazga III (handmade), Mundigak III, and Shahr-e Sokhta I. The use of red and yellow pigments noted at Namazga and Shahr-e Sokhta is unknown in Quetta, but provides a link to polychrome Nal pottery.

Simple lines and the bracket motif are hallmarks of the later stages (late Quetta, late Damb Sadaat III = Sadaat). Although the criteria for a proposed stylistic development from Damb Sadaat I-III are far from clear and the excavations at that site were small, in Mehrgarh typical Quetta ware appears in Period VI and late Quetta pottery in Period VII/Nausharo IA-C,

Figure 16 Mehrgarh, period VII, Quetta ware. Courtesy, French Mission to Mehrgarh, C. Jarrige.

Figure 15 Mehrgarh, period VII, Quetta ware. Courtesy French Mission to Mehrgarh, C. Jarrige.

A distribution that supports this scheme. At Sohr Damb II, few typical ‘Quetta’ sherds were found, but Sadaat types are common in Period III (Figure 18, lower left). The bracket motif is particularly common in southeastern Baluchistan, where it overlaps with Early Har-appan wares. A date into the later third millennium can thus be ruled out.

Since its discovery just after 1900, ‘Nal pottery’ has been divided into an earlier polychrome ware, marked by the application of yellow and turquoise after firing in addition to black and red, and a later monochrome series. Both share complex geometric patterns characterized by multiple contour lines, geometric designs with stepped borders, arranged in friezes and metopes, but the designs are more elaborate on the polychrome vessels (Figure 19). Realistic or abstract figurative motifs such as felines, bulls, birds, and hybrid creatures, and floral ornaments are also common (Figure 20). Despite the occurrence of repetitive designs, their composition and execution reveals many individual traits, and hardly two pieces are identical in detail, betraying artistic freedom and craft specialization of the potters, and probably a Highly symbolic meaning. Some of these motifs and structural principles can be seen on Quetta ware, but the polychromatic nature, the particular addition of structural elements into complex patterns, and the figurative motifs underline its originality.

Recent excavations at Sohr Damb/Nal, where this pottery occurs exclusively in Period II, have finally placed it into a cultural and chronological context. As a result, the notion of the polychrome ware as older and of its use a funerary ware has to be abandoned: it was found in vast numbers in domestic contexts, along with monochrome pottery. It appears fully fledged in Period II, but stylistic evolution is apparent. The discovery of a late Nal assemblage in 2006, marked by the lack of turquoise, a more careless execution and the use of a wider brush, confirms this impression. The new motifs and design are closely linked to Mehrgarh VII, Balakot, and other sites of the late Early Harappan Period in southeastern Baluchistan.

Nal pottery, or similar types, occur at Mehrgarh VI, Miri Qalat IIIa-b (Figure 21), Shahr-e Sokhta I-II (Figure 22), Tappe Yahya IVC1, and in the Kandahar region, where it was probably intrusive. Considering this wide distribution, its lack at the nearby Quetta sites, and vice versa, indicates the persistence of distinctive cultural zones. A similar pattern is reflected by painted gray wares. The Faiz Mohammad and the Emir Gray Ware share the distinctive technology of high temperature firing in a reduced atmosphere, but have distinctive shapes and motifs, and are rather localized with exclusive distribution patterns, notwithstanding overlaps. While the Emir Gray Ware predominates in the southwest, Shahr-e Sokhta I-III, Tappe Yahya VA-IVB5 (few), and Makran (Miri IIIb), the former was mainly found at Mehrgarh VI-VII and from Quetta to Surab, but rarely further south. At Sohr Damb, one vessel was found in a Period II tomb, carrying a pattern identical to that on a buff ware pot from Mehrgarh VII (Figures 16 and 17). The

Figure 17 Sohr Damb/Nal, period II: gray ware beaker, tomb 768. DAI, Eurasien, Ute Franke. Photo: A. Lange.

Figure 18 Sohr Damb/Nal, period III, pottery from Trench 9. DAI, Eurasien, Ute Franke. © 2008 Dr. Ute Franke-Vogt. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Co-occurrence of both gray ware types at Mundigak III-IV.1 revealed continued links of this site with both regions.

These patterns reflect the presence of two larger cultural regions within Baluchistan, a southern one which has connections with northern Baluchistan, but is also still oriented toward Iran, and a northern one that extends from Khuzdar to the Kachi plain and has affinities with southern Afghanistan and the western fringes of the Indus plains. Before we discuss the final centuries predating the rise of the Indus Civilization, we will have a look at southeastern Iran, where these horizons intermingled and urban centers developed.

World History

World History