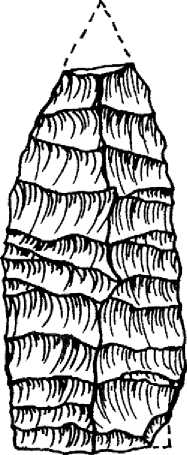

A hallmark artifact of the Late Paleoindian period is the Clovis point. So effective for hunting was this implement that its design proliferated among Paleo-indian peoples throughout much of North and Middle America. For the first time a tool was available to confidently confront the large animals that had previously been an attractive but elusive and often dangerous source of food. In Middle America scattered Clovis points have been recovered from both highland anD lowland regions, although all are isolated surface finds. Lacking context, their use, age, and the lifeways of the people that made them can only be inferred from sites further north in the United States.

The dozen or so Clovis finds from highland regions of Middle America area are distributed geographically from Sonora, Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo Leon, and Durango in northern Mexico, to San Luis Potosi, Quereitaro, Tlaxcala, Puebla, and Oaxaca in the Mexican central and southern highlands, down to Guatemala and Costa Rica. In the lowlands only three Clovis finds have been reported, all from Belize. Two are from Ladyville, north of Belize City, and the other was found near August Pine Ridge (Figure 4). As noted above, the Actun Halal Cave site might also date to this period.

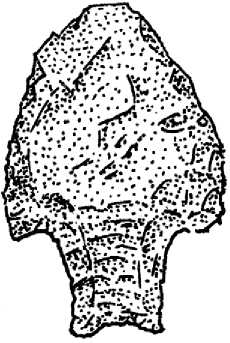

Another diagnostic Late Paleoindian artifact, contemporaneous and morphologically akin to Clovis, are the so-called Fishtail projectile points. Also fluted, they are distinguished from Clovis points by a characteristic stemmed base. Their origin appears to have been in South America, where they were first encountered at Fell’s Cave in the Tierra del Fuego region of Chile. Four are currently known from Belize, all surface finds, where they have been provisionally dated c. 9000-7000 years bc, based on their resemblance to better known examples at Madden Lake in Panama and the Quiche Basin of Guatemala (Figure 5). The August Pine Ridge Clovis point exhibits a degree of fishtail-like basal narrowing, suggesting that southern Middle America may have been the meeting point of the two traditions. Although no faunal remains have been associated with the Belize points, the open savanna environment where some of the specimens were found would have provided an appealing habitat for large, grazing animals. At the Fell’s Cave

Cm

Figure 5 Fishtail point from the Lowe Ranch Site (BAAR 35E), Belize. Reproduced with permission of the Robert S. Peabody Museum of Archaeology, Phillips Academy, Andover, MA.

Site, radiocarbon dated 9050 and 8770 years bc, Fishtail points were recovered in association with the remains of horse, mylodon, and other now-extinct Pleistocene animals.

Appearing somewhat later in time than Clovis and Fishtail points are a variety of large, unfluted lanceolate-shaped projectile points and knives, many of them dazzling in their technological refinement.

J_I

Cm

They are best known from the North American Southwest and Plains under such type names as Angostura, Dalton, Plainview, and Scottsbluff, but variants extend into other areas, including Middle America. At the La Calsada Rockshelter in the highland Mexico state of Nuevo Leton, similar tools have been radiocarbon dated to the beginning years of the Late Paleoindian period. While still associated with the hunting of Ice Age megafauna, these implements are increasingly found at sites witH bison, antelope and other modern prey, reflecting the changing composition of animals on the post-Pleistocene landscape during the final millennia of the Late Paleoindian period.

Also exemplifying this complex in Middle America are the Santa Isabel Iztapan finds, where the dismembered skeletons of two mammoths were discovered along the shores of ancient Lake Texcoco in the Valley of Mexico. Spear points comparable to Lerma, Scottsbluff, and Angostura types were found near the animals, along with an assortment of chert and obsidian knives and other butchering tools that were probably responsible for the many cut marks found on the fossil bones (Figure 6). As at the earlier Tlapa-coya site, the fact that the obsidian and chert from which many of the tools were manufactured were procured from sources many kilometers away indicates the mobility of these hunters or their participation in an early network of exchange with other bands. The location of the kill site suggests that the

(b)

(a)

Cm

(c)

Figure 6 Projectile/spear points found in association with the Santa Isabel Iztapan mammoths. a. Scottsbluff point; b. Lerma point;

C. Angostura point.

Animals were driven into or had attempted to escape along the swampy shore of the lake and were butchered on the spot.

In the North American Southwest and Plains regions the recovery of many large animal bones in Late Paleoindian period archaeological sites suggested that a ‘big game hunting tradition’ had evolved, a tradition that was ultimately shown to be inapplicable to Middle America. The initial negative evidence was provided by the Tehuaciin Archaeological-Botanical Project, a ground-breaking interdisciplinary study based in the highlands of Puebla, Mexico. The ambitious objective of the project was to reconstruct in a single place - the Tehuaciin Valley - a complete sequence of social and cultural development, from the time of earliest human settlement to the beginning of urban civilization.

Excavations at Tehuactin revealed that the earliest human occupants of the valley, between 12 000 and 9000 years ago, manufactured a variety of bifacially flaked stone tools, including Lerma - and Plainviewlike projectile points. Judging from the association of these implements with the remains of animals such as horse and antelope, it was apparent that big game hunting had indeed been practiced by these early settlers. But notably, analysis of the many bones recovered from birds, gophers, jackrabbits, rats, and turtles revealed that smaller animals actually constituted the bulk of the diet for the Tehuactin inhabitants. Recovered from an early stratigraphic zone in the valley’s Coxcatliin Cave, for example, were nearly 400 jackrabbit bones, including in a one square meter unit, the feet of over 40 animals that had been slaughtered in a single session.

The tendency of jackrabbits to congregate suggested that they were hunted in communal drives, involving people from several otherwise independent bands. However, as the environment changed during the Holocene, social species of animals, such as jack-rabbits and pronghorn antelopes, appear to have been supplanted by more solitary types, such as cottontail rabbits and white-tailed deer, a population shift that would have entailed the abandonment of communal hunting for the stalking of single animals by individuals or small groups of hunters.

Along with the fauna, the recovery in the Tehuaciin Valley of food remains from wild plants such as avocado, agave, and opuntia further indicates a much broader spectrum of subsistence than that implied by a ‘big game hunting’ model. Subsequent archaeological excavations at Cueva Blanca, several hundred kilometers further south in the Oaxaca Valley, corroborate the Tehuaciin reconstruction. Overall the Late Paleoindian mode of subsistence in highland Middle America appears to have involved generalized foraging, with small game constituting the bulk of the diet, supplemented by the occasional larger animal and the seasonal availability of wild food plants. Population density is estimated to have been very low, clustered into small, mobile ‘microbands’ consisting of four to eight related individuals. Mostly independent, several bands may have temporarily joined each year for hunting and perhaps social activities. The need to not overexploit the limited wild food carrying capacity of the habitat in places such as the Tehuactin and Oaxaca valleys would have induced the small bands to remain dispersed for most of the year.

Another of the defining attributes of the Late Pleistocene period is the dramatic disappearance of over 32 genera of large Ice Age animals, among them the mammoth, mastodon, horse, camel, tapir, ground sloth, dire wolf, saber-tooth tiger, and glyptodont. Since prior environmental fluctuations during earlier phases of the Ice Age had not resulted in similar extinctions, the growth of human population and the attendant development of more efficient hunting techniques have been proposed as the principal causal factor. Support for this Pleistocene Overkill hypothesis is strongest on the North American Plains where there is archaeological evidence of a shift in hunting strategy from the stalking of solitary prey to the often wasteful slaughter of entire animal herds in a single episode. Critics of the hypothesis respond that many of the species that became extinct were not hunted and some that were, such as the modern bison, did not perish. Evidence from the Tehuaciin Archaeological-Botanical Project indicates that at least for Middle America predation of Pleistocene megafauna was not intense enough to have accounted for their extermination. Overall, the explanation for the extinctions may lie in a combination of climatically induced environmental change and more intensive hunting.

World History

World History