The Mariana Islands

Evidence from sites such as Tarague Beach on Guam and Achugao Point, Chalan Piao, and Laulau on Saipan demonstrates that the settlement of the Marianas occurred by at least 3500 year BP. Some linguists have proposed a colonization of the Marianas by peoples from Taiwan, though others argue that Chamorro speakers have more immediate links to the Philippines. Recent genetic evidence suggests that the Marianas and Yap were probably settled independently from islands in Southeast Asia and that gene flow may have also occurred from

Figure 2 Swamp taro {Cyrtosperma chamissoni). Photo by Scott M. Fitzpatrick.

Central-eastern Micronesia. If the Marianas were settled from some part of Southeast Asia, it has been hypothesized that Yap and Palau might have been stepping stones to the northern reaches of western Micronesia, although it seems more likely that the Marianas were settled independently.

Ceramics found in the earliest occupation layers in the Marianas known as Achugao Incised and San Roque Incised are much different than other pottery traditions found in Micronesia. Some of the decorative techniques appear reminiscent of the dentate-stamped Lapita pottery found in the islands of Melanesia and western Polynesia. Achugao pottery has parallel incised lines in curved or rectilinear patterns around the necks of vessels with stamped or incised circle motifs with colored slips, usually in red or black. Decoration on the much rarer San Roque pottery consists of circular motifs. Lime was used to fill in the decoration on both ceramic types after firing. It has been suggested that pottery seen in the Marianas, as well as those ceramics from Luzon (northern Philippines) and Lapita, share similarities with the red-slipped pottery found in Yiian-shan assemblages in Taiwan. In addition to pottery, other artifacts such as beads and bracelets made from Conus shell are found.

Some of the more interesting features in Marianas prehistory are the latte stones made from limestone, sandstone, or basalt which begin to show up in the archaeological record around 1000 year BP. These stone pillars with capstones (tasa) were arranged in pairs numbering between three and seven (often occurring in clusters) and used to support house

Figures Latte stone from the Marianas. Photo by MichikoIntoh.

Structures. A study of 234 sets of latte on Guam found that over 80% were in sets of four or five and were rarely more than 2.5 m high. The House of Taga site on Tinian, however, has columns over 5 m high. Although there has been some debate about the true function of latte stones, it is likely that they served multiple purposes centering around habitation, domestic activities, and preventing rats from gaining access to food supplies. It is quite possible they also served other functions that were more ritual or symbolic in nature. Needless to say, the carving, transport, and use of latte stones clearly represent a gradual rise in Marianas’ social complexity (Figure 3).

The Western Caroline Islands

Prior to the late 1990s, early dates from Palau and Yap hovered around 2000 year BP, even after nearly 30 years of investigation. A wealth of archaeological information derived from cultural resource management projects on Koror and the large volcanic island of Babeldaob, as well as recent research in the smaller Rock Islands of Palau, now suggests that the settlement took place closer to around 30003300 year BP, nearly contemporaneous with the earliest prehistoric sites known in the Marianas. Good evidence for this period of occupation comes from Ulong Island and the Chelechol ra Orrak site which contains the oldest-known burials yet found in the Pacific Islands (c. 2800-3000 year BP). Palaeoenvir-onmental cores that show an increase in charcoal fragments (possibly from people burning forested Areas for growing crops), and pollen from plants transported by humans, suggest that human settlement may have occurred even earlier around 4500 year BP. However, similar to what is seen in the Marianas, no archaeological evidence has yet been found to support the early palaeoenvironmental dates and so it is still a debated issue whether human settlement did in fact take place this early.

Palauans appear to have genetic contributions from Southeast Asia, central-eastern Micronesia, and New Guinea, a reflection of their long history and geographical proximity to all three regions. Computer simulations of drift voyaging suggest that Palau was likely colonized by peoples from the southern Philippines (Mindanao), matching up well with the linguistic evidence.

Because of its ecological diversity, Palau has a number of species not found in the other islands such as the marine crocodile (Crocodylus porosus), which was present at historic contact, but was either rare or unimportant as a resource. Among larger marine vertebrates, the now endangered dugong (Dugong du-gong) was highly prized for its vertebras, which were worn as bracelets (klilt) by men of high status in Palauan society.

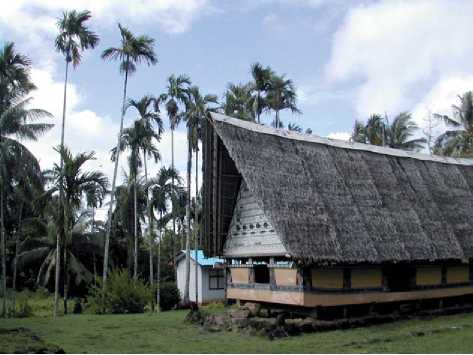

Palauans and Yapese both brought with them a number of important crops, the most important of which was taro (Cyrtosperma chamissonis) that was grown in swamp ponds. Although swamp taro was an extremely important crop to the Yapese, they also grew yams in gardens created by slashing and burning sections of the forest. In addition to the various plants that Western Carolinian populations purposefully brought with them for food were other cultigens that did not necessarily fulfill a dietary need, but still important culturally. These include nuts from the betel palm (Areca catechu), which is chewed in combination with pepper leaf (Piper betle) and slaked lime to produce a calming, euphoric effect in the user. Areca palms are an important cash crop today in Palau and Yap and are often found surrounding men’s houses or residences. Evidence for betel nut chewing in Palau dates back nearly 3000 years (Figure 4).

The initial colonizers of Palau probably focused on settling the larger islands of Babeldaob and Koror, although the smaller Rock Islands were also used for specific purposes such as burying the dead. By about 2500 year BP, people in Palau began constructing monumental earthworks along ridgelines such as terraces and later on, flat-topped ‘crown and brim’ formations. These large complexes are not found elsewhere in the Pacific Islands and probably served multiple functions that were agricultural, domestic,

Figure 4 Betel nut (Areca catechu) palms surrounding a traditional Palauan men’s house (bai). Photo by Scott M. Fitzpatrick.

Figure 5 Terrace formation on the island of Babeldaob in Palau. Photo by Calvin Emesiochel.

Ceremonial, defensive, and/or symbolic in nature (Figure 5).

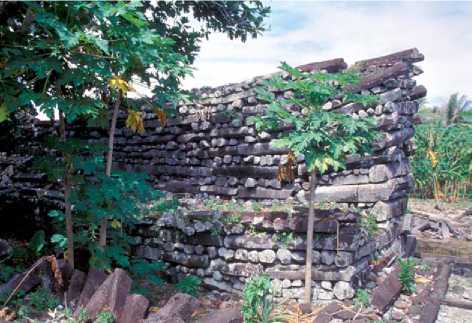

After 1500 year BP, most terraces were completely abandoned and stonework villages on both the coralline and volcanic islands are seen. By 800 year BP, ancient Palauan life was centered in these villages which contain a variety of stone architecture, including house and cooking platforms, meeting house (bai) foundations, docks, bathing areas, chiefly backrests, and extensive pathways that linked sections of the villages together. Not only were these stone constructions utilitarian and probably defensive, but platforms were used for interring the dead and served as indicators of status, rank, and power. When Europeans arrived, these villages were still in use and continue today as places of residence for many inhabitants. Artifacts commonly found at stonework village and other archaeological sites in Palau include Ceramics that were locally made and primarily tempered with ‘grog’ (crushed fragments of fired pottery); some earlier samples contain calcareous or volcanic sand. Ornaments and tools made from the giant clam, Terebra, and Conus, and stone tools are found, but the latter in much fewer numbers.

Archaeological research in Yap that began in the 1950s began to identify many features on the surface such as stone construction for house platforms, alignments, pathways, and walls. The earliest acceptable radiocarbon dates for Yap hover around 2000-2200 year BP and come from the sites of Pemrang and Rungruw at the southern end of Yap proper. Similar to many other Micronesian islands, the most ubiquitous artifacts found in Yap are ceramics, but with others made from shell and stone. The earliest ceramics contain calcareous sand-tempered (CST) pottery and after about 600 year BP, a laminated type becomes more common. However, like the Marianas and Palau, palaeoenvironmental sequences with charcoal and pollen suggest that initial settlement may have occurred a thousand years earlier, although further work is needed to substantiate these findings.

Genetically, the Yapese appear to have been independently settled from somewhere in Southeast Asia. The distribution of a particular genetic sequence on Yap and throughout central-eastern Micronesia suggests that these areas were linked culturally in the past. This is evidenced by the extensive exchange relations that were known historically between Yap and the coral atoll dwellers to the east.

When Europeans arrived, there were peoples living in over 140 villages on the four main islands of Yap (Yap, Maap, Rumung, and Gagil-Tamil), which were socially ranked - higher-ranked villages were located on the coast and lower-ranked ones were inland. As a result, the higher the ranking, the more privileged access these groups had to resources from the land and sea. However, these ranking systems were dynamic and could change as conflicts occurred, so it was critical that villages continually validate their ranking by establishing and maintaining exchange relationships with other groups, including those outside of Yap.

Some of the most dominant features of Yapese settlement are the faluw (young men’s house), pebaey (council house), stone paths, and taro gardens. Villages are divided into tabinaw or plots and often surrounded by hedges. Wunbey (paved plazas) are built on top of these. Other obvious markers of village life in Yap include their famous ‘stone money’ (rai) that can be seen lined up along pathways or in front of residences (Figure 6). These unusual disks are

Figure 6 Stone money disks (rai) set upright against the foundation of a residence in Yap. Photo by Michiko Intoh.

Usually circular or ovoid in shape and made from limestone quarried in the Rock Islands of Palau (see below). It has been proposed that as populations grew (perhaps as high as 30 000 people by the mid-1800s), the Yapese shifted from small-scale cultivation of crops on hillsides to coastal areas for growing taro. According to Japanese administration censuses taken during the turn of the nineteenth century, these numbers declined rapidly after contact to less than 8000.

The Central and Eastern Caroline Islands

Based on archaeological and linguistic evidence, the islands of Chuuk, Pohnpei, and Kosrae appear to have been first colonized by at least 2000 year BP from somewhere in southeast Melanesia or perhaps Fiji/western Polynesia. The languages here are classified into a subgroup of Oceanic languages called Nuclear Micronesian, which implies that the initial settlers of these islands probably came from somewhere in the vicinity of early Lapita expansion between the Bismarcks and the Solomons or Vanuata.

Artifactually, all of the high islands in the Central and Eastern Carolines have CST pottery during initial colonization at 2000 year BP. However, the manufacturing of pottery ceases on all of these islands by about 700 year BP or slightly before. Various theories have been proposed to account for why peoples here and in other parts of the Pacific stopped making pottery, but it could be tied to a number of factors, including a change in cooking practices or a breakdown of trade relations in which pottery played a part in transferring goods.

For subsistence, those islands around the central part of Micronesia such as Chuuk tend to rely on taro, but also breadfruit which is seasonally available. The Piper methysticum plant, known as kava in Polynesia, was also brought into Pohnpei and Kosrae where it is known as sekau or seka, respectively. The roots of this pepper plant are pounded into a pulp on a large basalt sekau stone which are often found in prehistoric and modern villages. To prepare the drink, the pulp is strained with water by twisting it through the inner strips of bark from the hibiscus tree. The sekau/seka is shared in a communal cup by users, which usually numbs the mouth, relaxes the individual, and increases the senses.

Some archaeologists have suggested that Pohnpei, the third largest island in Micronesia (330 km2), was originally settled by peoples around 2300-3000 year BP due to similarities in language, agriculture, and artifacts - this is slightly earlier than the most well-accepted chronologies dating closer to 2000 year BP. The most common types of archaeological sites found on Pohnpei are those with stone architecture. The site of Nan Madol, built on nearly 100 artificially constructed islets covering 80 ha, is constructed of large foundation boulders used to support columnar basalt columns. It is by far the most impressive example of stonework in Micronesia (and arguably the Pacific) and represents one of the finest examples of architectural prowess known in prehistoric Oceania. The site contains dozens of structures, including stone enclosures, platforms, and tombs. Also affectionately known as the ‘Venice of the Pacific’ because of the channels that can be accessed by boat during higher tides, Nan Madol construction began around 1500 year BP and lasted for about 1000 years with the most intensive building taking place during the last few hundred years of its use. These structures have been interpreted as serving as chiefly residences for the island’s elite ruling class known as the Saude-leur. According to oral traditions, the Saudeleur dynasty was later overthrown by an invading group around 500 year BP by a man called Isohkelekel who led 333 warriors in a battle to defeat the ruling class. Other stone constructions found on Pohnpei include vaults or tombs (lolong), platforms (pehi), and enclosures (keltakai). After about 1000 year BP, adzes made from Terebra and Mitre shell appear, and 200 years later pearl shell trolling lures are found (Figures 7 and 8).

The colonization of Kosrae was probably contemporaneous with other islands in the Central and Eastern Carolines, although limited palaeoenvironmental research suggests that the island was colonized earlier around 2500 year BP. The best-known site on Kosrae, located on Leluh Island, is similar to Nan Madol in that it was constructed using columnar basalt columns to form walls and foundations. The site covers an area of 27 ha with a canal running through the center

Figure 7 The corner of a tomb enclosure at the Nan Madol site known as Nan Douwas. Photo by Scott M. Fitzpatrick.

Figure 8 Columnar basalt columns used to construct the wall of a structure at Nan Madol in Pohnpei. Photo by Scott M. Fitzpatrick.

Of the site to allow access to the sea. The site is said to be the residence of the paramount chief and his subchiefs. Pottery recovered here is similar to late Lapita plainware, but shares closer affinities with pottery from Chuuk. Through time, the population began to increase, especially between 300 and 900 year BP, and groups began more intensively settling the coastal margins and upper valleys. By 500-600 year BP, nearly all of the major land areas, including the coastlines, flatter uplands, and islands in mangrove, have evidence for prehistoric habitation. At contact, populations are estimated to have reached between 7000 and 10 000 people, but declined rapidly after European Contact; only a few hundred people were estimated to be living on Kosrae in the 1870s.

Of the three high islands in this region of Micronesia, Chuuk (formerly known as ‘Truk’) has received the least attention archaeologically, although it does have some of the best evidence for historic sites dating to the Japanese administrative period and World War II (WWII). The earliest settlement of Chuuk is found on the island of Fefan dating to around 2000 year BP, but could be slightly earlier. Some archaeological deposits found within the intertidal zone off Fefan are indicative of stilt houses being constructed. The cultural chronology for Chuuk is somewhat vague with a long ‘gap’ of a thousand years between 700 and 1500 year BP where little information exists about prehistoric settlement.

The Winas Phase probably represents the initial settlement of Chuuk lagoon and the sites on Fefan island may contain the oldest pottery-bearing sites in central and eastern Micronesia. Ceramic vessels are typically CST plain bowls or pots with little to no decoration. Tridacna shell tools and Conus ornaments are also found, reminiscent of those seen in the Solomon Islands. The later Tonnachaw Phase lasts from 700 year BP to the present. No ceramics are present, but a number of other artifacts are found such as coral pounders, Terebra shell adzes, and breadfruit peelers made from cowry shells. Archaeologists have identified seven major site types on the island, most of which are associated with later periods of occupation. These include coastal residences with lineage houses (wuteyches), coastal wuuts (canoe houses), interior residences that were domestic in nature, interior fanang (cookhouses), ridge and summit sites that are midden rich, forts with rock-wall structures located at higher elevations, and rock art.

The Marshall Islands

The Marshall Islands are probably best known for being used as an atomic testing ground by the US military after WWII. In total, 67 devices were detonated between 1946 and 1958, all of which took place on either Bikini or Enewetak atoll. Because of the focus placed on the Marshalls during and after WWII, there are extensive historic remains on the islands such as concrete bunkers, artillery, and wreckage of planes and other vehicles, although good evidence is emerging that the islands were intensively settled prehistorically as well.

Several extremely early radiocarbon dates have been collected from Bikini that date from about 2800-3500 years ago, but they are much older than other chronological sequences and are considered dubious by most researchers. It is likely that settlement of the Marshalls took place closer to around 2000 year BP based on dates from several atolls including Kwajalein, Bikini, and Majuro. Linguistic models suggest the Marshalls were colonized by groups originating in eastern Melanesia; this is also supported by computer simulations of voyaging, but it is also possible that peoples moved northward through Tuvlau and Kiribati from Fiji.

Although atolls are rich in marine foods, prehistoric Marshallese also cultivated crops in order to survive on these small, remote islands. Differences in rainfall between the northern and southern Marshall Islands led to the giant swamp taro Cyrtosperma and breadfruit being emphasized in the more southerly and wet islands, and coconut and pandanus in the northern and more arid islands. Dozens of archaeological sites have been identified in the Marshalls and as expected, nearly all of the portable artifacts found In these sites are made from bone and shell due to the lack of local volcanic stone. Examples include shell adzes made from Cassis, Conus, Lambis, and Tri-dacna, Spondylus beads, and Conus rings. Pearl shell was also used to manufacture trolling lures and fishhooks. The few stone artifacts found in archaeological deposits may have been made from stone that drifted to the islands on driftwood masses. Twenty-nine burials at Laura village on Majuro that date to 1400-1800 year BP and contain hundreds of ornaments such as beads, shell rings, and a few bone and shell tools testify to inhabitants caring for the deceased during the early prehistoric period.

Kiribati

Relatively little is known about the prehistory of Kiribati, a likely result of their remoteness and lack of good accessibility, but also a feeling by past researchers that the settlement of these smaller atolls and limestone islands lacked stratified deposits or were peripheral to the understanding of Pacific settlement compared to other high island groups. We now know this not to be the case and there has been a steady increase by archaeologists since the early 1980s to investigate these types of island throughout Micronesia.

Linguistically, peoples in Kiribati as in the Central and Eastern Carolines speak languages within Nuclear Micronesian. A majority of the archaeological work conducted on prehistoric settlement in Kiribati has been done in the Gilberts. Excavations on the island of Makin by Japanese archaeologists revealed cultural deposits at a depth of over 3 m that dated to around 1600 year BP. The artifacts found, including fishing lures made from Cassis shell, appear to be closely related to those found in eastern Polynesia. Studies conducted later on the islands of Tarawa and Tamana revealed a diversity of fishing gear such as fishhooks and lure shanks, shell beads, and pavement and alignments made from coral rock. More recent archaeological work on Nikunau shows that prehistoric peoples were building earth ovens using coral and clam shells.

World History

World History