Cultural remains, along with a few hominid fossils, dating to the Middle Pleistocene are found in most parts of China, although they are concentrated on lowlands and river plains. Hominid adaptations to Different environments are reflected by regional variations in the lithic industries. During this period, cave sites were significant settlement locations for homi-nids, and important cave sites are often found in central-northern, northeastern, and southwestern China. Open-air sites along river valleys and lake shorelines, like those in the Nihewan Basin, were continuously occupied. The most important innovation for the Middle Pleistocene hominids was the intentional use of fires.

Cave Sites

Major cave sites during this period include Zhoudou-dian Locality 1 in Beijing, Jinliushan and Miaohoushan in Liaoning province, Longyadong in Shaanxi province, and Panxian Dadong in Guizhou province. These cave sites yielded some of the most important evidence of hominid behavior, technology, and settlement pattern.

Located southwest of Beijing, Zhoudoudian Locality 1 is famous for the discovery of five Homo erectus skulls in 1929. At one time it was the most celebrated Palaeolithic site in the world and still is a national monument in China. After three-quarters of a century, the cave site is still the Palaeolithic site that yielded the most abundant Homo erectus fossils remains in China (more than 40 individuals). Considered as a home base, the cultural deposition in the cave is over 30 m thick, and is divided into 13 layers (Figure 7). Investigations of its cultural chronology suggest that the cave was at least repeatedly occupied for at least three different phases, the first from 500 to 400 thousand years ago, the second 400 to 300 thousand years ago, and the third from 300 to 200 thousand years ago. Faunal assemblages from occupations in the cave and dating to different times, indicate climatic changes in the region throughout the Middle Pleistocene period. There is rich evidence of fire ash deposits within the cave; however, whether the fire was caused intentionally by hominids or was the result of natural fires is currently under debate.

The lithic industry at the Zhoukoudian Locality 1 cave may be characterized in general as having small flake tools (most less than 40 mm in length) produced by the bipolar technique. However, lithic assemblages from the Early, Middle, and Late occupational phases clearly differ: large-sized tools like choppers and points decreased in number over times, while the number of small tools like scrapers, burins, and notches increased through time. Tool-making technique was also changed with bipolar flake removal being replaced with direct percussion at the Middle Phase. Noticeably, good-quality local raw materials like chert were used in increasing quantities at the Late Phase, although

Figure 7 The Zhoukoudian Locality 1 Cave site with deposit stratigraphy (right).

Figure 8 The No. 9 ash patch in Layer 8, Level 7, at Jinniushan. The scale is in centimeters.

Quartz and quartzite were still predominantly selected by Zhoukoudian hominids.

During the Late Phase of Zhoukoudian occupations, hominids with different biological features, namely Archaic Homo sapiens, are found to have lived at the Jinniushan cave near Dashiqiao city in southern Liaoling province. Identified in 1978, the Jinnuishan Locality A cave, measuring roughly 13.5 m long east-west and 9 m wide north-south, was excavated completely over the course of a multiyear field project that ran from 1986 to 1994 by the Peking University. The site is exposed with 11 layers of sediments with geological age dated to the Middle Pleistocene.

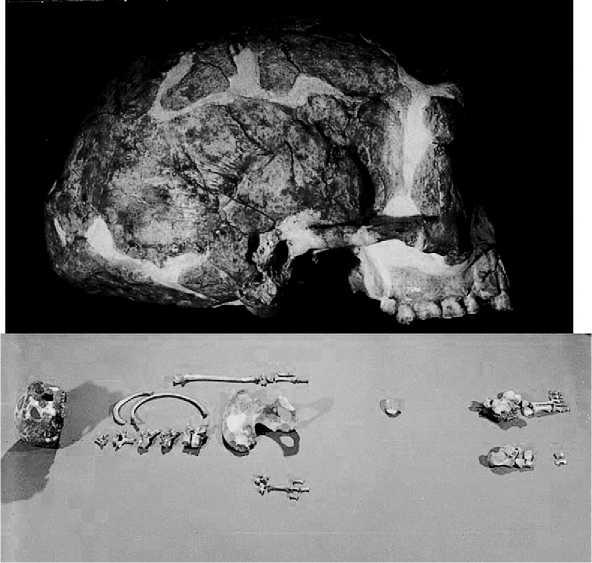

Jinnuishan cultural remains were found in Layer 8, and included more than 200 lithic artifacts, 9789 faunal remains (nearly 200 with burnt marks), and nine well-preserved fire-use ash features (Figure 8). The most important discovery was more than 50 specimens of hominid fossils, all found within 2 m of the southern wall of the cave. These fossils belong to a single female, approximately 20-22 years old, now known as the ‘Jinnuishan hominid’ (Figure 9). Uranium-series dating suggests a date range of between 300 and 230 thousand years ago, with an average date of 263 thousand years ago.

The Jinnuishan hominid cultural remains suggest that two different hominids coexisted in northern China during the Middle to Late Pleistocene. The associate fossil faunal remains of rhinoceros and macaque suggest a warmer and wetter environment. The Jinniushan hominid might have lived in small groups (of probably less than a dozen), inhabited caves seasonally, and used as well as preserved fire.

Figure 9 Fossil remains of the Jinnuishan Archaic Homo sapiens.

The discovery of Guanyingdong cave in 1964 was a breakthrough in that for the first time Asian homi-nid cultural remains were well represented in the Southwest where Early Palaeolithic sites were still limited. Rich cultural materials recovered from the cave indicate a southern lithic industry different from the Zhoukoudian industry during late Middle Pleistocene to early Upper Pleistocene. Hominid fossil remains recovered from this area include a few teeth from cave sites of Tongzi Yanhuidong and Panxian Dadong. These teeth show biological features more closely related to Archaic Homo sapiens than to Homo erectus.

Dadong is a large karst cave located 50 km southwest of Panxian city, at an altitude of 1630 m above sea level. The cave’s main chamber with an average of 35 m width and extending over 200 m in length covers roughly 8000 m2 in area. Several field excavations were carried out in the 1990s, yielding a large number of lithic artifacts as well as faunal remains that represent the Ailuropoda-Stegodon faunas of Middle Pleistocene southern China. Uranium-series dates and electron spin resonance (ESR) dates of tooth enamel place the majority of the archaeological deposits between 130 and 250 thousand years ago (see Electron Spin Resonance Dating).

Studies of lithic assemblages suggest that Dadong hominids utilized poor quality but locally available limestone for tool-making, while basalt and chert were increasingly used in later times as hominids extended their explorations of the area. It is suggested that an anvil-chipping technique was possibly employed as a mode of core reduction to make flake-tool blanks, evident by large limestone blocks in the cave. Dadong hominids might have modified and used animal teeth of suitable size and shape as working tools as an alternative to the poor-quality local limestone. Taphonomic study of faunal remains from the cave yields a high quantity of large-bodied animal teeth, especially those of rhinoceroses. These must have been intentionally selected and transported to the cave by hominids for functional purposes.

Hominid fossils, associated with abundant faunal remains, are also recovered from caves in southern China (especially along the Middle and Lower Reaches of Yangtze River) such as Hexian Longtangdong and Chaoxian Yingshan in Anhui province, and Nanjing Tangshan in Jiangsu province. These archaeological deposits of Homo erectus (Hexian and Nanjing fossils) or Archaic Homo Sapiens (Chaoxian fossils) are roughly dated as contemporaneous to the Zhoukoudian occupational period. The recent discovery of Sanming Lingfengdong in Fujian province has proven to be the largest and richest late Middle Pleistocene cave occupation in southeast China, although no hominid fossil was found.

Open-air Site

One of the important open-air sites during this period is Lantian Chenjiawozi site where the famous Hom o erectus lower jaw was recovered in 1963. In general this jaw, together with the skull recovered from Gang-wangling, have been identified as Lantian hominids. But the Chenjiawozi jaw is dated to 700-600 thousand years ago, later than those fossils from Gangwangling. Another open-air site, Dali in southern Shaanxi province, yielded a well-preserved skull belonging to a 30-year-old Archaic Homo sapiens individual.

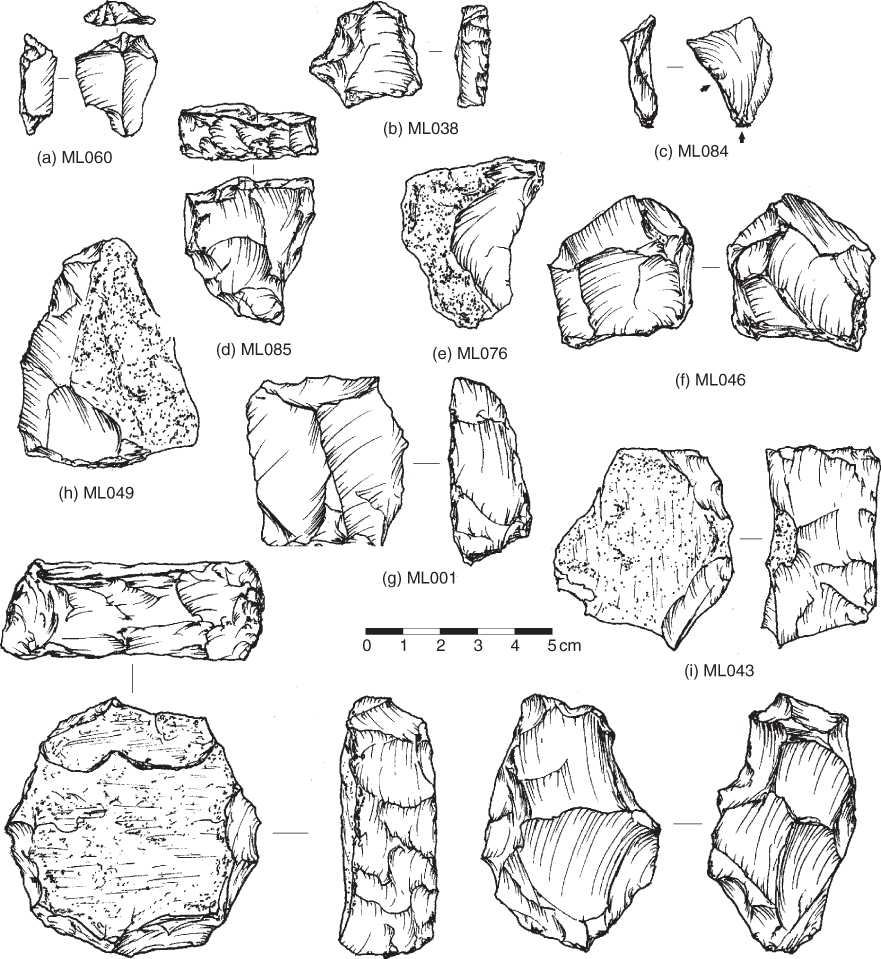

In the Nihewan Basin, the Middle Pleistocene sites are represented by Maliang, Qiuergou, and Qingciyao. A study of Maliang lithic artifacts, recovered from the 1984 excavation session, suggests that Maliang homi-nids have developed more skills in tool-making skills than their predecessors, an example being the increased sophistication of multidirectional core reduction. Flake tools were modified into standard shapes of scrapes and notches, which are not seen in other earlier assemblages (Figure 10). They learned to select fine-quality chert which is available but rare in the region,

(j) ML042 (k)

Figure 10 Lithic artifacts from the Maliang Site. (cores: f, k; end-scrapers: a, d; side-scraper: b; tablet-shaped object: i, j; modified flake: g; flakes: c, e, f)

Suggestive of developing hominid cognition and their procurement strategies. Use-wear analyses indicate that tool use at Maliang probably emphasized on bone scraping/shaving functions (Figure 11) (see Lithics: Analysis, Use Wear).

Most open-air sites are usually found in clusters along river valleys. Some are located on upper lands, at the third to fifth terraces of mountainous regions, such as those in the Luonan Basin in southern Shaanxi province and in the Baise (or Bose) Basin in Guangxi province. In the past two decades, a large number of Early Palaeolithic sites are found at lower elevations on river flood plains in southern China. The important Early Palaeolithic complexes include those from Hanzhong Basin in Hubei/Shaaxi provinces, the Lishui Valley of Middle Yangtze River in Hunan province, and the Shuiyangjiang Valley of Lower Yangtze River in Anhui province. Within each of these complexes, dozens of open-air sites are found in close proximity, embedded within the same geological deposit, and share similar features of lithic assemblages. These complexes present a unique local industry adapted to river valley settlements over the time of the Middle Pleistocene.

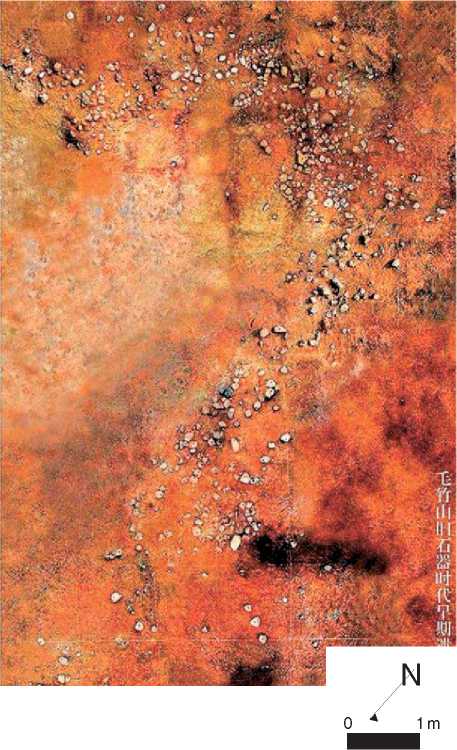

Recent investigations in the Shuiyangjiang Valley have identified more than 20 palaeolithic sites, representing the earliest Palaeolithic settlement concentration in the Lower Reach of Yangtze River. These sites have a date range between 817 and 126 thousand years ago based on ESR dating. Within the complex, the discovery of the Maozhushan site in 1996 revealed an important open campsite, with a pebble

(c

Figure 11 Use-wear of Miliang lithic artifacts. (a) ML085, x14. Heavily rounded edge with used polish along the working edge, scattered scars are moderate to large in size with stepped and hinged termination, unifacially distributed on the dorsal surface. The wear type is indicative of scraping hard bone. (b) ML001, x28. Moderate to large scars bifacially distributed along the edge of 10-15 mm. Scars are directional but most are vertical to the edge, heavy rounding and rare polish. Interpreted as cutting/sawing hard bones use-wear. (c) ML060, dorsal side, x56. small-to-moderate-sized feathered or hinged scars, unifacially distributed along the edge on dorsal side. (d) ML060, Ventral side, x28. Heavy rounding and polish along ventral-sided working edge (opposite to that in previous photo). A few striations parallel or perpendicular to the edge are noted. The combination of wear patterns is suggestive of scraping wood use-wear.

Semicircle structure that could be the earliest structure created by early hominid in China (Figure 12).

The Maozhushan site is located 4.5 km northwest of Ningguo City, Anhui province, on riverine terrain about 65 m above the sea level. The settlement lies on the second terrace of the Shuiyangjiang River covering a hilly landscape of nearly 4000 m2, of which an

Figure 12 Plan view of pebble semicircle at the Maozhushan site.

Area of 13 x 15 m2 was exposed in the 1997-1998 field season. The stone structure is made of more than 1100 pebbles, featuring a semicircular shape with a 10 m long east-west axis and a 6 m north-south axis. What is more interesting about this structure is that 20 small pebble circles, ranging from 20 to 30 cm in diameter, were found on the edge of the pebble semicircle (Figure 13). Although the current evidenCe is insufficient for identifying the function of this structure, it is suggested that all of the pebbles for the semicircle structure were purposefully collected by hominids elsewhere, and those pebble stones also served as raw materials for tool making. It has been speculated that some small circles together with stone artifacts could be evidence of the use of post molds, thus a possible implication of the earliest wooden shelter known in China. However, lack of faunal remains and the organic components of the sediment are due to acid earth in the study region of southern China.

A total of 154 stone artifacts were recovered from the pebble semicircle at the Maozhushan site. They were scattered evenly throughout the structure and no patterned clusters of lithic artifacts could be identified. Typologically, the lithic assemblage primarily consisted of chunks, cores, and flakes. Tool types included scrapers, hammers, choppers, points, picks, spheroids, and drills. Some tools showed traces of possible use. The pebble semicircle might have been a seasonal living structure where tool-making activities were conducted; however, the specific function of this structure needs further investigation. Judging from the evidence at present, the Maozhushan site may have been a central campsite of the Shuiyangjiang River Paleolithic complex.

Palaeolithic Settlements at the Luonan Basin

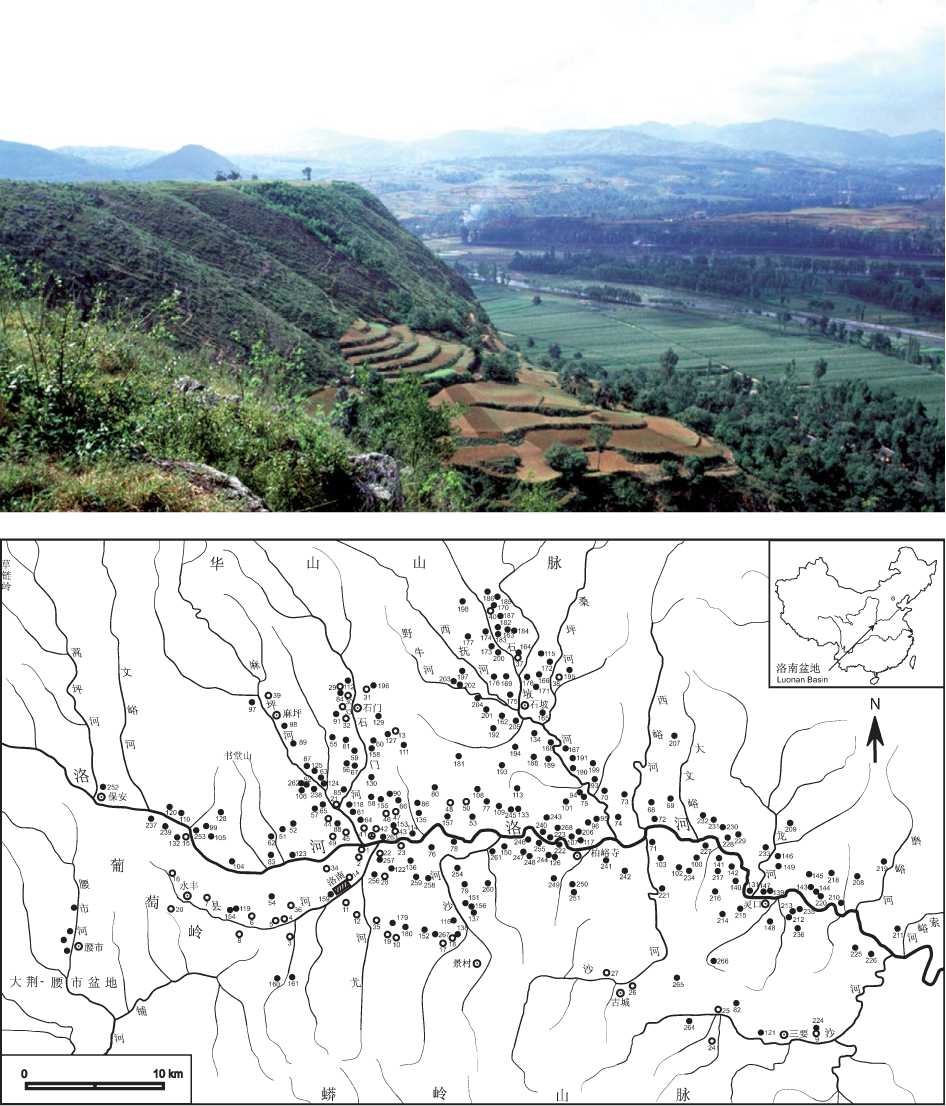

The Luonan Basin is located in the Qinling Mountains which form a geographic boundary between northern and southern China. The basin contains caves

Figure 13 Examples of small pebble circles at the Maozhushan site.

And open-air sites that date to at least 350 000180 000 years ago, distributed over the second to sixth terraces of the river valleys. Archaeological surveys for Palaeolithic sites started in 1995, and by 2004, a Sino-Canada research collaboration identified a total of 268 open-air sites and one cave site of Early Palaeolithic (Figure 14).

Excavated between 1995 and 1997, the Longyadong cave is relatively small, about 20 m2 in area. The cultural deposits are about 3.5 m in depth, and contain three cultural layers. Fired ash remains were clearly identified on these layers. Artifacts from these ‘living floors’ were in substantially high density (the average 1000 pieces (>10mm)perm3), and over 77000 lithic

Figure 14 The Luonan Basin landscape (upper) and the Lower Palaeolithic sites.

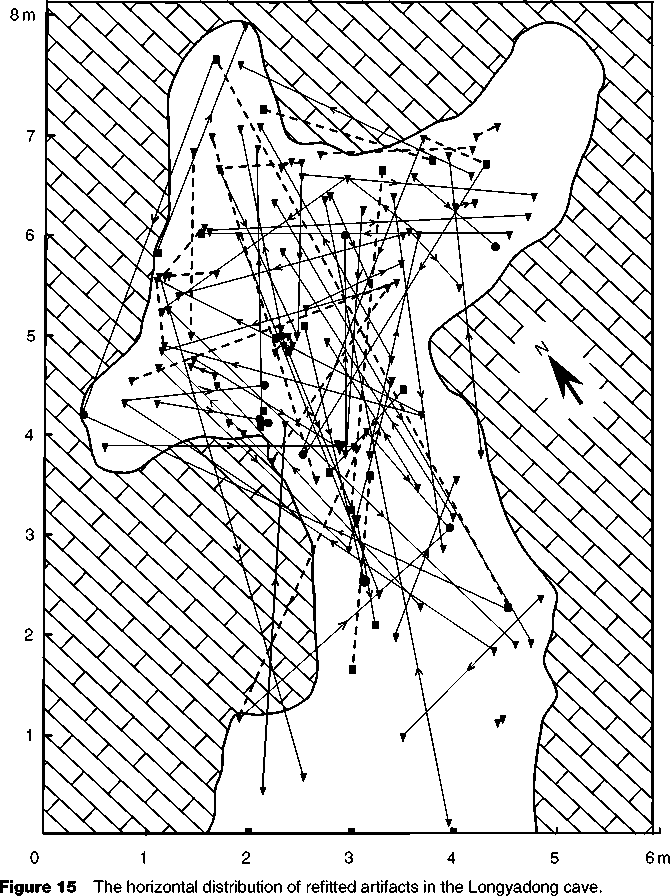

Artifacts were recovered from the cave. Cores, nodules, anvils, and other breccia rocks were arranged along the circumference of these ‘floors,’ while numerous flakes and fossil remains were concentrated in the center. Refitting study was successful in conjoining thousands of artifacts within the cave to document site formation and hominid spatial use of the cave (Figure 15).

The difference between the open-air sites and the cave sites are analyzed in terms of the raw materials and tool-making technology. The study shows that stone tool types from Longyadong cave site are dominated by small modified flake tools like scrapers, points, and burins. Large choppers made on pebble stone are present but in a very low number. In contrast, 13 581 pieces collected from 268 open-air sites consists of large tool types that are not seen from the cave sites, such as hand axes, picks, cleavers, spheroids, and choppers in relatively high numbers. It is implied that the Longyadong cave may have been one of the central sites of occupation where early homi-nids visited repeatedly over a long period of time, while the open-air sites were loci of their temporary activities. The differences in tool assemblages show that there might have been different site functions between the cave and open-air sites.

Lithic Technology

During the Middle Pleistocene, two main lithic technologies were established as strategic adaptations: flake tools in northern China and pebble-core tools in southern China. Flake tools were produced with directly percussion or bipolar percussion by expedient core reduction. Based on the current data, no

Cores

Flakes or retouched flake tools Flaking debris

Conjoining refitted sequences Joining broken pieces

Standard core platform preparation has been detected as yet. Predominant flake blanks were modified into scrapers, notches, and burins. Raw materials mainly consisted of poor-quality quartz and quartzite which were common locally available resources. Good-quality cherts were also selected during the later period at some sites.

The majority of pebble-core tools were found at riverside sites in southern China, and were made by either freehand percussion or anvil-chipping methods. The difference between pebble-core tools and flake tools is that the former were bifacially or unifacially made on cores or large flakes. These types of tools often included large cutting implements like choppers with either bifacially or unifacially chipped edges, large bifacial or unifacial points, and other heavy-duty tools like spheroids.

However, differences between the two lithic industries were also observed in comparisons of cave sites and open-air settlements, especially in southern China. Some caves, like Dadong and Guanyindong, yielded primarily flake tools that contrasted with the lithic assemblages from contemporaneous sites in adjunct areas. These differences could be direct reflections of site functions, as representations of homi-nid behavior. In fact, the difference between the lithic assemblages of the Longyadong cave and other open-air sites, as mentioned above, could also be explained as the result of cultural interaction between southern and northern hominids, particularly in light of the fact that the location of the Luonan Basin was on the boundary where the two lithic technologies could have met. Clearly, further study on the Luonan lithic assemblages in terms of dating and chronology, site formation, stone tool functions, will shed new lights on the diversity of hominid behaviors in the Middle Pleistocene China.

Handaxes in China

Another important aspect of the Luonan Basin Palaeolithic is the discovery of over 200 handaxes from open-air sites (Figure 16). This is one of the largest clusters of so-called Acheulean-like handaxes in China. The other areas yielding a large number of handaxes are the Baise Basin in Guangxi province and the Danjiangkuo Reservoir area in northern Hubei province. A few handaxes are also reported, in lower numbers, from other open-air sites, in both northern and southern China.

At present well-known handaxes assemblages are reported from Baise, where the Palaeolithic complex consisted of nearly 100 sites and localities, distributing mainly on the fourth terraces of the 100 km-long Youjiang River valley. About 25-100 m above the present river level, the artifact-bearing deposits of the fourth terraces are associated with tektites dispersed across the basin. The age of these large cutting tools were established by 40Ar/39Ar analyses on collected tektite samples, and yielded an average age of 803 thousand years ago. Thus, Baise handaxes are claimed to be the oldest large cutting tools in East Asia.

It is suggested that the both Luonan and Baise handaxes exhibits all the traits of the Acheulean technology from western Eurasia/Africa. These handaxes were made of pebble cores, bifacially chipped to straighten the working edge towards the tip, but leaving cortex and rough working surface near proximal (butt) end. It is also evident that handaxes with similar morphological traits to Chinese tools are found in Chongokni, Korea. Compared to the classic Acheulean handaxes in the West, these eastern versions seem to be crudely made prototypes. However, technologically, they share similar attributes of human modification to those in the West. The difference in their appearance may be caused by use of different raw materials, and possibly by different functions as a result of adaptive behaviors to the East Asian environment.

The discovery of handaxes has always stirred sensational discussion focusing on the concept of the ‘Movius Line’ that drew developmental differences between elaborate handaxe culture in the West and crude chopper-chopping culture in the East. Since the first identification of handaxes from the Dingcun site in southern Shanxi province in 1954, Chinese scholars were trying to claim that Palaeolithic cultures were not from the cultural backwaters as implied by H. Movius’ syntheses in the 1940s. Today, it is clear that Chinese hominids produced cultures quite different to those of their counterparts in Europe and Africa. Regardless of whether the large cutting tools (including hand axes, cleavers, and picks) are similar or dissimilar to those in the West in terms of measurement or attributes, the reasons why handaxes in such form appeared in China would be of interest to Palaeolithic research for years to come. For example, archaeologists working on the Baise assemblages believe that production of handaxes could be a behavioral adaptation to an episode of woody plants burning and widespread forest destruction due to tektite events that resulted in local cobble outcrops becoming available.

World History

World History